1 st place part 2

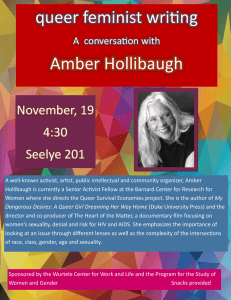

advertisement

Jay Vites SOC 108 10 Nov 2014 Queer Youth & Homelessness De Castell, S., & Jenson, J. (2006). No place like home: sexuality, community, and identity among street-involved "queer and questioning" youth. McGill Journal of Education, 41(3), 227-247. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/2027170 42?accountid=38295 Canadian queer street-involved youths were asked their idea on “home:” what it is, what it means to them, and the kind of home that they could thrive in. Using this information, a fundraiser was established to help create safe, queer-friendly housing that suited the needs of these LGBT youths. The fundraiser also helped queer youths during the production of the project by offering meals, training, pay for work, and condoms in order to give an advantage to street-involved marginalized youths. The article then goes on to explain, through the experiences of these street queer youths, how the current education system unfairly disenfranchises marginalized students by ignoring the worth of other ways of meaning-making (that aren’t linked to typical, literatureheavy education). Dysart-Gale, D. (2010). Social justice and social determinants of health: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, intersexed, and queer youth in canada. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(1), 23-8. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/2329655 25?accountid=38295 Examines the nursing value of social justice, where nurses are obligated to be informed, educated, and trained to assist LGBTIQ youth in medical needs. A large factor in proper health is shelter, which many LGBTIQ teens are without due to homelessness from families that don’t approve of marginalized sexualities. Abuse and bullying may also come from family homes or homeless shelters, where LGBTIQ teens are at risk. Queer homeless youth can turn to prostitution as a means of living, and face abuse and STI risks in this way. Misunderstanding, bias, and homophobia play into why these queer youth’s healthcare needs aren’t being met. Fine, L. E. (2012). The context of creating space: Assessing the likelihood of college LGBT center presence. Journal of College Student Development, 53(2), 285-299. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1010412 669?accountid=38295 Fine assesses the lack of LGBTQ resource centers on university and college campuses in America, which only causes more tension and hostility for LGBT students that face harassment or bullying on campus or in their personal lives. The author introduces social movement theory as a lens to analyze the benefits that LGBTQ college centers could bring to students, including resource mobilization and political opportunity. Fine argues that access to resources will only allow LGBTQ students to succeed further in getting their voices heard on campus and working with administration to solve any queer-related problems that exist. LGBTQ centers for students can also help to prevent homelessness or provide resources for those struggling at home. Moskowitz, A., Stein, J. A., & Lightfoot, M. (2013). The mediating roles of stress and maladaptive behaviors on self-harm and suicide attempts among runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(7), 1015-27. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9793-4 The authors discuss how different variables like gender, age, sexual orientation, parental drug use, and emotional distress can predict self-harm and suicidal behavior in youth in runaway and homeless youth, especially those that are LGBTQ, since they are statistically more likely to deal with both self-harm and suicidal ideation. Stress and maladaptive behaviors are focused on as correlated causes for both self-harm and suicidal ideation in LGBT homeless youth, who face higher risks of both than non-homeless youth. Nolan, T. C. (2006). Outcomes for a transitional living program serving LGBTQ youth in new york city. Child Welfare, 85(2), 385-406. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/2138088 37?accountid=38295 Nolan provides information from a housing program in New York based on LGBTQ youth needs. They discuss the issues to consider when dealing with homeless LGBTQ teens—such as prostitution, drug use and addiction, HIV and STIs, and untreated medical problems. By applying changes for the needs of these queer youth, shelters can prevent homeless youth from ageing into homeless adults with even more problems. Nolan also recognizes that homeless queer youth are even more susceptible to individual and institutional homophobia/transphobia than those in safe homes with parental, emotional support. Transitional housing programs are examined on whether they are successful with the queer youth that are discharged from their programs. Pritchard, E. D. (2013). For colored kids who committed suicide, our outrage isn't enough: Queer youth of color, bullying, and the discursive limits of identity and safety. Harvard Educational Review, 83(2), 320-345,401-402. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1399327 209?accountid=38295 Pritchard discusses the lack of intersectionality within the discourse of gender- or sexualitybiased bullying and violence against LGBTQ youth. They argue that anti-bullying campaigns and safe spaces are still an issue of race, class, and gender rather than an issue solely related to marginalized sexualities or gender presentation. The article acknowledges that identity is not flat, that there are multiple facets to any individual and thus, every facet of an individual that identifies as queer will have an effect on their experiences with bullying, violence, homelessness, etc. Because of these intersectional aspects of queer youth, homeless shelters become hazardous and dangerous places for LGBT teens to seek safety. Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., & Hunter, J. (2012). Homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Implications for subsequent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(5), 544-60. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964011-9681-3 Rosario explains factors that correlate with homeless LGB youth, including mental health (anxiety and depression), conduct problems, substance abuse, and childhood sexual trauma. Findings suggest that reduced levels of stress and emotional/social support can reduce negative psychological symptoms in homeless or previously-homeless LGB youth. Statistics show that LGBT youth are overrepresented in the homeless population, making up about 15-36% of homeless youth, while only 1-3% of youths are LGBT. Sakamoto, I., Chin, M., Chapra, A., & Ricciardi, J. (2009). A 'normative' homeless woman?: marginalisation, emotional injury and social support of transwomen experiencing homelessness. Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review, 5(1), 2-19. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/2140441 30?accountid=38295 The article reviews the hardships and quality of life for homeless trans women, who regularly face discrimination, attacks, and violence due to transphobia, heteronormativity, poverty, and lack of shelter. The relationships between homeless trans women and homeless cis women are examined and described as a network of emotional support for each other, especially in instances where female-only shelters are hostile towards trans women. Even in supposedly queer-safe villages, many gay residents work to keep trans people (mainly trans women) out of the neighborhood, thus denying shelter even within the LGBTQ community. Stanley, E. A., & Spade, D. (2012). Queering prison abolition, now? American Quarterly, 64(1), 115-127,183. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1013806 181?accountid=38295 Intellectual activists discuss the involvement of the queer community in prison abolition, and how queer rights align with the disruption of the current American prison system. LGBTQ people rally against the strictly enforced heteronormativity, archaic gender roles, white supremacy, and ableism that is rampant in prison systems today. Because queer people are socially labeled as deviant and criminal, homeless queer youth face an even higher chance of incarceration at the hands of the oppressors that are not sympathetic to their condition. Van Leeuwen, J.,M., Boyle, S., Salomonsen-Sautel, S., D, N. B., & al, e. (2006). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: An eight-city public health perspective. Child Welfare, 85(2), 151-70. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canyons.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/2138102 31?accountid=38295 The article provides a review of a health survey completed by LGB and non-LGB homeless youth to assess the levels of care and needs that are/are not being met by community services. It aims to reveal the gaps in areas where more training and resources are necessary to adequately offer equal health services to LGB homeless youth. A significant number of homeless youth report medical needs for drug and alcohol use, as well as an increase in risk of STIs from prostitution or survival sex.