1302 Research Essay Sample.doc

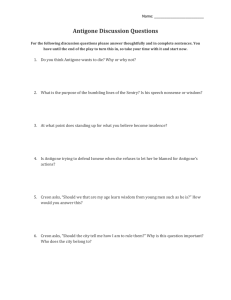

advertisement

Group # 1 Students’ Names Dr. Laurel Lacroix English 1302 April 30, 2012 Antigone: Lessons of Civic Discourse through Tragedy In Attic theatre, plays served as avenues for poets to teach the audience lessons on civic discourse, or how to be a good citizen within the city-state. Antigone, written by Sophocles, is a tragedy that provides lessons to both its ancient and modern audiences. The play ends tragically with three deaths, Antigone, Haemon and Eurydice. Their deaths symbolize the need for democracy, deliberation, and reason. Antigone stood for the laws of the divine and the loyalty to the family. Her actions and her strong will draw the admirations of the audience. Yet, what we admire about Antigone the most is also her flaw. Antigone is the third play in the trilogy which includes Oedipus Tyrannus and Oedipus as Colonus. The trilogy seeks to teach the audience a lesson in civic discourse. These lessons pertain to the ways in which citizens come to judgment and resolution. Antigone provides the audience with a tragic climatic exciting resolution that leaves one to rethink the morality of the actions which brought each character to their individual fates. The play, Antigone, embodies the Aristotelian formula for tragedy in the aspects of conflict, character flaws and anagnorisis in order to provide a lesson in civic discourse for Ancient Athenians that still applies to modern readers today. Throughout the course of Antigone, the four primary themes throughout the play address the conflict of divine law (nomina) with civic law, the subservient roles of women in ancient Greece, the curse of the House of Oedipus, and the approval from the gods for individual and civic actions. The primary theme was the precedence of the divine law, which allowed for burial Group # 2 of relatives and the conflict with the proclamation of the civic law, whose primary goal and focus was the preservation and obedience to the state. As part of this preservation, traitors would not be allowed a proper burial and the desecrated bodies would be left to serve as a warning to all. .Through this edict, many thought Creon failed to respect the fundamental categories of existence and the passage from life to death as marked by the rite of burial, consigning those above to a wall beneath the earth. To leave the dead unburied or to bury the living was to threaten this fundamental order and bring chaos and ruin. Women’s subservient roles with the Greek city-state were another major theme throughout Antigone. Creon wanted nothing more than to ignore Antigone and Ismene’s pleas for burial and attempted to separate and denigrate their character in hopes of their obedience to his edict. Nevertheless, Antigone’s defiance of Creon’s order will ultimately bring ruin to Creon’s family and leadership. The curse of the House of Oedipus and its predetermined effect on kinship will affect Creon’s rule. No matter how he might revel in his new position as ruler of Thebes, his kinship to the two remaining sons of Oedipus and his confrontation with Antigone will bring destruction and ruin. The approbation of the gods and their reticence for intervention will color the actions of the characters. The characters, chorus, and messengers will attempt to garner the support of the gods for approval of their actions. The gods’ reticence to intercede and stop the tragic events however ultimately determines the course of action. It is through the prologue that the two sisters, Antigone and Ismene will emerge from the skene, the palace of Thebes, and discuss the repulsion of the Archive attacks, the deaths of their remaining brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, and the edict of Creon forbidding the burial of Polynices. The audience will also be reminded of pollution caused by the house of Oedipus. Creon refusal for a proper burial for Polynices will be the reason for the dramatic confrontation Group # 3 between the two sisters. Antigone’s outrage, passion, and defiance will be the center of action throughout the play, ultimately serving to break the kinship and bond with her apathetic yet adoring sister, Ismene, and destroy and ruin to the house of her uncle, Creon, the newly appoint king. Ismene cannot countenance the reckless folly of defying the edict of the king but Antigone cannot tolerate what she sees as disloyalty to the dead. Both sisters recognize their secondary status afforded to women in Thebes, but it is Antigone and belatedly Ismene, who is willing to defy the laws of the state put forth by Creon and exercise her virtue in following the nomina, the burial of relatives. Antigone’s resolve to bury her dead brother because of an absolute familial obligation, recognition of the gods’ will to honor the dead, and the avoidance of dishonor by the citizens will characterize her heroic status. Thought the gods are silent, both Ismene and Antigone will claim the approval of the gods for their respective views. Initially Antigone welcomed the kinship with Ismene. Antigone is all too aware that the sins of Oedipus has deprived them of their parents and now, of the two remaining brothers, Eteocles and Polyneices. Though both brothers have died, Antigone is not concerned with Eteocles’s death because he has at least received his due of burial rites. The play, Antigone, written by Sophocles between 445-438 BC, proves to be one of the most controversial plays in this era. As the third play of the Oedipus Trilogy it provides the audience with lessons of civic discourse through family values and political values. Sophocles was born in Attica at Colonus “496 B.C ” about a mile from the city of Athens, and died “406 B.C” (Beer xiv, xvii). He was well educated in all of the arts, such as dance, poetry, philosophy, and music. Sophocles took on a political and dramatic career. Sophocles was thought of as a man at ease with himself and content with life. Antigone is Sophocle’s 32nd written play. Group # 4 The date of Antigone’s production has brought up many controversies. In one source it is said that Antigone was produced between “445-438 B.C” and that the “date of 441 is dubious” (Beer xvi). Vicker concludes that the involvement of an unburied corpse seems to mimic the events “after the fall of Samos to Pericles in 439 B.C, when prisoners were allegedly crucified, clubbed and left unburied ” (Vickers 14). Thus, the year 438 B.C seemed more suitable to the production of Sophocle’s Antigone. Dramatic festivals were held in honor of Dionysus, in Athens. Dionysus is the god of happy life, wine, vitality, and ritual madness. “The traditional dating for the organization of the City Dionysia is 534” (Beer 31). “At first only tragedies and dithyrambs were performed, but comedies were included in 486. The performances of the plays were competitive, and prizes would be awarded to the winning choruses. Each playwright had four plays shown in succession on a single day. The competition in Greek culture served as a background to the invention of Greek politics” (Beer 31). This festival was so cherished that all courts were closed, and prisoners were released so they could attend the event. “The Dionysia was an event during which the Athenians took great pride in their own political and military achievements and used the occasion, in the presence of foreign guests, to incite admiration ” (Beer 35). Sophocles introduced new innovations to tragedy, “the introduction of the third actor and skenographia” (Beer 25). Skenographia was essentially the painted scenery or the location. The skene was placed in the play to create an illusion. “In Sophoclean tragedy, the skene helps to define the dramatic situation of the protagonists and often conceals the root causes of the tragic dilemma” (Beer 28). This means that the skene was placed to create a different type of depth to the play in which the audience could see or hear, such as a scream in the background or a painted backdrop. The theatre was divided into three sections- skene, orchestra, and auditorium. The Group # 5 skene “had a roof that could support actors, when required” (Beer 37). The roof was most of the time used for the appearance of the Greek Gods. In front of the skene was the orchestra, or “the dancing area” (Beer 38). Leading into the orchestra from the sides closest to the skene were two passageways, called parodoi. One parodoi was thought to lead into the town and the other would lead out of the town. This idea of the leading paradoi worked for Antigone, which was set in a polis. Sophocles’ uses of the paradoi in Antigone are evident, and take the conflicts in Antigone to a deeper level. Burial rights were seen as a religious practice and were reserved as traditions for the members of the oikoi to perform. In Antigone, however, the recent limitations enforced by the polis conflict with the traditions of oikos. “Traditionally, funerals had been the private domain of the individual oikoi” (Beer 67). The oikoi being the family. The care for the dead, and the rightful burial of the bodies, was highly respected and seen as a religious act that should be necessary for peace of spirit. Female members of the oikois were the ones who did the preparing of the body for burial. Dead traitors could be denied burial rights inside the city limits, and their body would be thrown out of the city, and buried either by the family or the inhabitants of the area. There were some Greeks that did not think of the burial of the dead as necessary by divine law. Most known was the philosopher Socrates, who expressed “utter indifference as to how, or even whether, he should be buried,” with the idea that “once he is dead, he will no longer exist in his body” (Arhensdorf 102). Socrates suggests that the idea of the dead to “live on in their corpses is an ‘evil’ of the soul” (Arhensdorf 102). Socrates was executed for impiety. It is important to know the mythological family history of the character Antigone in order to fully comprehend the play as set in Greek tragedy. In Oedipus Tyrannus, the main character, Oedipus born from Laius and Jocasta, runs from prophecy. Laius, to avoid prophecy of his own Group # 6 death by Oedipus, abandons Oedipus. Eventually Oedipus unknowingly fulfills part of the prophecy and kills a stranger who is Laius, by meeting on a road. Oedipus enters Thebes and becomes the first person to answer the Sphinx’s riddle correctly. He is rewarded for answering correctly by marrying Jocasta, his mother, without realizing that he is her son. Oedipus is now the king of Thebes and has had two daughters and to sons. Later the God’s demand vengeance for the death of Laius, and in return will lift the plague off the city. Oedipus is determined to find the killer. In his efforts to seek justice Oedipus finds out that he is indeed the killer of his own father. Jocasta figures out the secret and kills herself. Oedipus finds her body and takes out his own eyes, then leaves the position of king to Creon, Jocasta’s brother. He asks Creon to banish him from the city, and Oedipus leaves under the care of Antigone. In the play Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus approaches Colonus, with the assistance of his daughter, Antigone. They find that they are standing on sacred ground of the Eumenides. Colonus demands that Theseus, king of Athens, be brought to him. Ismene now informs Oedipus that he is wanted back at Thebes to escape his fate. He refuses to return and asks Theseus if he may die and be buried in Colonus, in return for a blessing over the city. Theseus agrees to help Oedipus. Creon enters threatening war and holding Oedipus’ daughter’s hostage if Oedipus does not return to Thebes. Theseus drives off Creon and rescues the daughters. Polyneices enters and asks for Oedipus’ help in his war to regain the Thebian rule over Creon and his brother. Oedipus is upset by this and tells that the brother’s will die by eachothers hands in battle. Oedipus hears thunder and realizes his death is near. Since Oedipus dies at Colonus, the city receives his blessing. Thebes gains Oedipus’ curse. Antigone and Ismene return to Thebes. After the death of Oedipus, the throne was handed to his two sons, Polyneices and Eteocles, to rule alternately (McManus 2). However, Eteocles after ruling for his first year refused to relinquish the throne to his brother Polyneices who in return Group # 7 attacked Thebes in attempt to regain power (McManus 2). Polyneices “was married to the daughter of the king of Argos” and “led the Argives and six other cities in an assault on Thebes” (McManus 2). During the battle both Polyneices and Eteocles were killed, leaving Oedipus’s two remaining daughters, Antigone and Ismene. Therefore, Creon, Jocasta’s brother, was crowned the ruler of Thebes (McManus 2). Once Creon became the ruler he was faced with the task of how to bury the two brothers. Since, Eteocles had defended the city of Thebes, Creon decreed that he “shall be entombed, and crowned with every rite that follows the noblest dead to their rest” (Sophocles). Polyneices, however, was now considered a traitor to the city because he led the Argive assault on the city. Creon declared that “none shall grace him with sepulture or lament, but leave him unburied, a corpse for birds and dogs to eat, a ghastly sight of shame” (Sophocles). As the play begins, Antigone desperately seeks out her sister Ismene and informs her of Creon’s decree. She then tells Ismene of her plans to give her brother, Polyneices, a proper burial and asks Ismene to help her. Ismene denies Antigone’s request to assist her in betraying Creon’s decree proclaiming that first they “were born women, as who should not strive with men” and that she will not “defy the state” with Antigone (Sophocles). Antigone then goes to Polyneices’s body and performs ancient burial rites such as sprinkling dust and oil over his body. The guards discover what she has done and inform Creon, who infuriated, condemns both Antigone and Ismene to death for defiance of his laws. Haemon, Creon’s son, was set to be married to Antigone, and upon hearing that his father condemned his future wife to death protests to Creon. Finally, Creon, eases up somewhat and releases Ismene but orders Antigone to sealed alive in a cave where he can “hide her, living, in rocky vault, with so much food set forth as piety prescribes, that the city may avoid a public stain” (Sophocles). The prophet, Teiresias, then visits Creon and tells him that “the avenging Group # 8 destroyers lie in wait for thee, the Furies of Hades and of the gods, that thou mayest be taken in these same ills” (Sophocles). Now that Creon is frightened by this prophesy, he tries to undo his wrongdoings. He rushes to bury Polyneices body and then to the cave where he had sealed Antigone alive to free her. However, he is too late and upon his arrival to the cave he discovers that Antigone has hung herself and Haemon who arrived before Creon found Antigone as dead as well and commits a desperate suicide in front of his father Creon. Word soon travels back to Creon’s house of his son Haemon’s fate, and his wife, Eurydice, upon hearing the news of her son kills herself too, all while cursing Creon. The play ends with Creon realizing his wrongdoing and prays that he may never look upon to-morrow's light” (Sophocles). The major characters in Antigone develop throughout the course of the play. Antigone is the main character in the play and is best known for her defiance of Creon’s law. She represents femininity in that her “deep and undying affection for her kindred” is the force behind her actions (Haigh 2). However, she contradicts her femininity with masculine actions such as defying the state. She reasons that “a law of man which violates religious law is no law at all” (Thompson and Grote 1). Antigone is determined to follow the laws and traditions of the gods even in the face of dire consequences. She is devoted to the family and shows her loyalty through her defiance of Creon’s law. Her character ultimately suffers from her own self will. She commits suicide once she is entombed in the cave by Creon. If Antigone only had waited a little longer for Creon to free her or if she had deliberated and argued more, her fate may have been different. Antigone is ultimately characterized by both her family loyalty and by her stubbornness and powerful will. Creon, the ruler of Thebes, is concerned with keeping the order of the city. He sees defiance to his rule as unacceptable and uses extreme means to punish those who defy his laws. However, this attention to order supersedes the laws of the divine and Group # 9 ultimately makes Creon out to be a tyrant leader, resulting in grave misfortune. Creon places his focus on the polis or the city state in the face of the oikos or the family. He is determined not to have his authority undermined especially by a woman. Showing leniency to those who break the law, even to members of the royal family, would make Creon out to be a weak ruler to the people of Thebes. As the play progresses, Creon ultimately recognizes his error and that he was too quick to condemn Antigone. His actions resulted in Antigone’s suicide, Haemon’s (his son) suicide, and his beloved wife Eurydice’s suicide. Creon is left alive as a tragic twist of fate to suffer from the consequences of his tyrant rule. Ismene, Antigone’s sister, seems to keep the traditional role of women in ancient Greece. When refusing to help Antigone defy Creon, she claims that “women cannot fight with men, as they are stronger” (Antigone 1). Ismene views women as not being able to stand up to the laws of men. In the beginning of the play she warns Antigone not to defy Creon because it is important for the citizens to keep the laws of the state. However, later in the play, Ismene displays her loyalty to family and her feminine gender role as she tells Antigone that she will share in her fate. Unfortunately, Antigone is too far gone, she has already decided that she will go at it alone and refuses Ismene’s offer. Haemon, Creon’s son and Antigone’s future husband, tries to reason with Creon about his harsh punishment for Antigone. Antigone never enlists the help of Haemon even though they are betrothed. In fact, Antigone never seems to give care or mention to him at all. Despite this, Haemon pleads with Creon, his father, in favor of Antigone. He tries to reason with Creon and prove to him that his ways are wrong. Ultimately, Haemon's attempts to save Antigone fail. He goes to the cave where she is entombed only to find her dead after an apparent suicide. Creon shows up shortly after Haemon’s discovery in the cave. Haemon curses Creon and then commits suicide himself. It is somewhat unclear if Haemon tried to kill Creon as well. Even though Haemon is reasonable throughout the Group # 10 play, his love for Antigone overpowers his reason when he discovers that she is dead and he commits a desperate suicide out of despair. Teiresias is a blind prophet. He comes to Creon and gives him a prophecy. Tiresias explains to Creon that the gods are very angry with him for leaving a corpse unburied. He tells Creon that his actions will have dire consequences. This prophecy is what partly convinces Creon to rethink his actions. Creon becomes afraid and tries to rush and bury Polyneices and free Antigone from the cave. Eurydice is Creon’s wife. She is also Haemon’s mother. When Eurydice learns of her son’s suicide she herself also commits suicide out of despair. She curses Creon just before she takes her own life. She does not take a large role in the play, yet her actions add to Creon’s tragic fate. The chorus throughout the play seems to flip flop on their judgment of Antigone (Haigh 2). In the beginning the chorus “without actually approving of Creon’s decree, rebuke Antigone for her contumacy” (Haigh 2). They give the impression that they do not agree with her defiance toward the state. However, as the play progresses their judgment sways in favor of Antigone. At end of the play, the chorus then becomes firm in their judgment that Antigone was just in her actions because “reverence for the gods must be preserved inviolate” (qtd. In Haigh 2). The chorus believes that Creon was wrong and should have been reasonable. They do not believe that he should have defied the laws of the divine in favor of the laws of man. The main conflict in the play is whether human law (polis law) can be defied due to the superiority of divine law (oikoi law) which contradicts it. Antigone believes that divine law is superior to human law. She defies Creon and thus human law by performing burial rites for her brother Polyneices. She appeals to their kinship and claims that it is the will of the gods. Creon however believes that human law and maintaining order is more important than divine laws. Creon becomes somewhat of a tyrant as he refuses to listen to any reason including that from his Group # 11 son Haemon. He only begins to waiver in his actions when the prophet, Teiresias, tells him that the gods are angered by him and that great ills will befall him. So, Creon in the end listens to the divine law and tries to undo his actions only to realize that he is too late and will now have to suffer from the losses of his wife, son, and future daughter in law. The chorus emphasizes this conflict throughout the play in their wavering judgment of Antigone. They exemplify the intensity of this conflict. Both sides seem to have somewhat valid reasons for their actions. Creon is attempting to hold order and authority over the city, while Antigone is attempting to stay true to the traditions of the family and the laws of the gods. However, the poet’s intentions are clear in the end because the chorus and Creon admit that he is wrong. Loyalty to both the family and the state and the contradicting actions of the characters in these loyalties is a major theme which develops throughout the course of the play. Antigone is loyal to her family, as she believes it is important to bury Polyneices no matter the consequences. However, as will be discussed later, her loyalty may be one of her flaws, as it does not seem to be evenly distributed to other members of the family. Ismene, in the beginning, refuses to help Antigone and in doing so displays her loyalty to the state. Yet, later in the play, Ismene offers her help to Antigone who then refuses it. This refusal on Antigone’s behalf seems to be a contradiction of her character. Antigone claims to be so loyal to her family that she will accept death to give her brother a proper burial; but she refuses her sister’s help ultimately. Antigone does not realize that it is her family’s help (Ismene’s and Haemon’s) that she truly needs in order to influence Creon to allow Polyneices burial. Creon is loyal to the state. He believes that Polyneices was a traitor to Thebes and thus does not deserve a proper burial. He condemns Antigone and Ismene for their defiance of his decree. Creon is attempting to prove his authority to the people of Thebes. If he declares a law and then allows a citizen to defy the law without Group # 12 punishment he will be seen as a weak ruler and will ultimately lose his power and authority to run the state. Creon is stubborn at first in his decision. He will not allow anyone to go unpunished, especially if it is a woman who is attempting to defy him. At the time of the play, women were not to be involved in matters of the state. Antigone through her defiance plants herself right in the middle of the state and casts away her femininity. At the end of the play, Creon realizes that the loyalty to his family should have been more important than the loyalty to the state in influencing his decisions. He learns the hard way as he loses both his wife and son for his actions. The lyric exchange between Creon, the cold spoken lines of the chorus, and the messenger is heightened with just the bodies of Haemon and Eurydice. Antigone’s absence prevented lamentations and her reburial to avoid the appearance the gods had relented – they had redressed the balance, not merely by punishing Creon for his crimes, but by giving posthumous reward to Antigone. The tragic fate that Creon suffers leads the audience to the conclusion that Creon was in the wrong for disobeying the laws of the gods. It also shows the audience that the way in which Creon made decrees and decisions was not constructive and that a less stubborn and tyrannical view would have been more beneficial. Creon could have avoided the schism within the kinship of the family and the country. His folly brought forth the distaste of the gods and their tacit approval for the madness of Haemon, and the allowance of the death of Antigone and Eurydice. Creon stubbornness and pride ultimately rendered him subservient to Antigone and severed the kinship of his family. Though the house of Oedipus may have affected the course of action for Antigone and Ismene, it was Creon’s response to them and his impiety to the gods with the polluted unburied corpse that eventually brought the destruction and ruin to the city of Thebes. Wisdom, though cherished by Creon, came too late to reverse destruction and ruin. Group # 13 In addition to the theme of loyalty, the theme of burial in Antigone illustrates certain values of ancient Greek tradition and family that are present in the play’s plot. Polyneices lead an attack on the city of Thebes in an attempt to gain power of the throne. His brother, Eteocles, was the king of Thebes at the time. The two brothers and their armies battled and they both ended up dying. Polyneices, for his actions, was now viewed as a traitor to the city. Creon did not want to give Polyneices a proper burial because he wanted to show that traitors and enemies to the state would not be shown any mercy in order to assert his new power and authority. The idea of proper burial for the dead was not an idea original to Sophocles, yet, it was taken from the historical context in which the play was written. Other playwrights at the time also discussed “Thebes’ refusal to allow the burial of the corpses of the invading Argive army”, which was the army that Polyneices led in Antigone (Markell 6). This refusal allegedly “provoked a heroic Athenian expedition to recover the bodies” (Markell 6). The ancient Greeks viewed properly burying a body as a form of respect (Markell 7). The burial of a family member confirms their identity within the family and provides an avenue for the people of all generations to show respect for the person deceased. In the play, Creon views Polyneices as a traitor to the city of Thebes and Eteocles as loyal to Thebes. Therefore, when both brothers pass he decides that Polyneices does not deserve the respect of a proper burial since he is considered a traitor. Antigone views her brother’s death not that of a traitor but of a family member. She believes that above all he is her brother first and foremost and therefore deserves a proper burial. Antigone claims that the rules of the gods, which regarded proper burial of any deceased person as necessary, are of greater importance in this circumstance than are the laws of humans. She claims that a “mortal” cannot “override the unwritten and unfailing laws of heaven” (Sophocles). Creon claims that “a foe is never a friend-not even in death” (Sophocles). He believes that Group # 14 because Polyneices is an enemy he will stay an enemy even in his death and therefore does not deserve to be buried like a family member would. Antigone decides to defy Creon and perform her kinship duties to her brother’s corpse. In the beginning of the play she intends to actually bury his body, but this was a task traditionally reserved for men (Markell 11). Instead, Antigone performs duties commonly reserved for women and sprinkles dust over Polyneices’ body. In ancient Greece, the women were the ones who would wash and dress the bodies for the graves and pour libations over the tombs (Markell 11). Antigone keeps to the traditions and roles of women in the family by performing these funeral rites for Polyneices. The polis is the political structure of the Greek city-state. The size of the Athens polis consisted of only a few thousand people. Women were “minors”, subject to male masters, and had no political power. “A polis was a small, close-knit community of citizens, even if they were dependent on others for their existence and survival” (Beer 4). It was important for the citizens to “defend their polis at all costs and be ready to die for it” (Beer 5). So an army would basically consist of the polis citizens with weapons. “Each polis was built at root on a collection of oikoi” (Beer 5). Oikoi means, house, family, or household. The head of the oikos was always the alpha male, and “his prime responsibility was to preserve the economic and social interests of the oikos” (Beer 5). The women were subordinate to the head male, and marriages were arranged for them, even if there was no romantic interest. Most of the wives were much younger then the husbands. Aristocratic oikoi was established long before the democratic polis, and conflicting traditions often created tension between the two groups. Tragedy uses the debates of the groups as a main conflict. Greek religion was polytheistic, consisting of several different gods, each different in their purpose, the well known were the twelve Olympians, like Zeus or Apollo. The religion was Group # 15 mainly polis based, and was expressed by “religious observances” (Beer 8) such as sacrifice, prayer, or festivals. Tragedy was mainly based on the traditions of the Greek and Athenian culture. In Antigone the skene depicts the royal house of Thebes, the first paradoi leads into the center of Thebes, the other leads away from Thebes to where the two brothers died. Creon represents the polis of Thebes. The House of Thebes is represented by the oikos. The opposition of the two sides to the conflict is given stage reality by the places of entrance and exit of the dramatis personae” (Beer 69). The conflict between Creon and Antigone in the play is between the oikoi, and polis stances on rights and values. Creon threatens the order of the gods by denying Polyneices any burial. By not allowing a body to receive any type of burial rights, Creon turns against his oikois values, and polis values. In the first scene Antigone and Ismene emerge from the oikos, which represents their place of birth. This first piece of the play instantly moves into conflict from unity. The two sisters are now similar to their brothers, but are divided by the edict of Creon. Ismene’s “obedience to her male masters serves to throw into relief Antigone’s rebellion” (Beer 70). Antigone and Ismene, who are members of the same oikos, become enemies because of the conflicting ideas of the polis and oikos. At the end of the prologue scene Antigone exits to the site of Polyneices body and intends to disobey Creon’s edict, while Ismene returns back into the oikos “where women conventionally belong” (Beer 70). The first episode differs with an allmale cast, who enters from the “city” parodos. Creon believes that the only way to create friends or enemies is through the polis. It is interesting to bring out the point that Sophocle’s has Creon repeat his new law to the chorus, but because Antigone introduced the conflict first she looks superior over Creon. Gender roles such as this will be more evident throughout the play. Group # 16 Continuing on Creon receives news from a sentry that was guarding Polyneices’ body that it seems that dust was thrown on his body. Creon’s reaction to the guard’s message of disobedience to his edict will reveal elements of his character with his accusation of bribery. Creon’s accusation to the guard of bribery, the lowest form of monetary interaction as claimed by Aristotle in Poetics, and the cause of ruin among its citizens, weakens his leadership, especially when the chorus does not accept Creon’s view that the guards were bribed. The warnings of public sentiment by Haemon for the burials and the prophecies of Tiresias will also reveal his poor leadership and flaws in his character and judgement. Sophocles uses the repetitiveness word “welcome”, welcome to my father, welcome to you my mother, and welcome to you my own brother to emphasize her rationale for why she had no other choice but to take the route she did. Her husband and children are replaceable but given that both parents are in Hades, she could never replace her bother, Polynices. Regardless of circumstances, she was right to honor her brother and is seems a credible, reasonable, and probable course of action which Sophocle’s audience would accept and which would fall within the realms of the play as claimed by Aristotle in Poetics. The chorus wonders whether this was an act of a god’s disapproval, and proposes that maybe Creon’s actions were wrong. Creon is upset that the gods disagree with his law, and instead blames a man. Creon’s blame is put to a male, and the thought of a female doing such an act is non existent. Creon is blind to the true criminal enters the oikos. Antigone who is caught committing the act of burial rights is lead to Creon. Polyneices receives two burial rights, the suggestion the chorus made previously now has a basis. Antigone is quick to admit her actions and justifies them, stating that she does not believe that Creon’s edict overpowers that of the Gods. Knowing that performing the burial would probably kill her, she thinks of her death as a Group # 17 gain. Antigone’s speech relates to the tradition that the oikos has the duty to bury its own members without disturbance from the polis. Ismene attempts to share Antigone’s punishment. Antigone denies her own oikos, by denying Ismene’s attempts to share the punishment. Antigone, who so strongly believes the oikos unity is stronger than that of the polis now separates her own sister, who has a sudden change of heart. Still, Ismene challenges the acts of Creon, asking why he would want to kill Haemon’s future bride. Creon responds to Ismene stating that “there are other furrows he can plant” (Gibbons 137) making a reference to the future “wedding ceremony” of Antigone. Creon sentences both Antigone and Ismene to death. Creon has been challenged by the parodos that leads to the body, and by the oikos. He will soon be challenged by the city parodos, first by Haemon, then by the prophet Teiresias. Haemon’s argument with Creon is basically an insult battle. Creon is upset that Haemon’s desire for Antigone is greater than his desire for the obedience of the polis. Creon’s is so worried about the gain of the polis, that he becomes “oblivious to his own oikos” (Beer 75). Haemon tells his father that the polis is in favor of the release of Antigone. Killing Antigone would make Creon look like a tyrant fool. In the eyes of Creon, Haemon has become too influenced by his love for Antigone and does not notice how she defied the polis and is a traitor. The first choral song heralds the successful triumph of Creon over the Argive armies against the city of Thebes. T heir reckless impiety and aggression will be punished by Zeus and will set the stage for the proclamation of the denial of burial rites for Polynices and the ensuing conflict between Creon and Antigone. Sophocles moves the play from the darkness of the conflict between the two sisters to the bright light of day. The heroic exploits furnish the background of this tragedy and Sophocles uses the well placed metaphors and vivid verbs as seen in Aristotle Poetics to celebrate the Group # 18 victory and herald the entrance of Creon, the new leader of Thebes. Metaphors such as the white shield describing the Argive armies, the serpent’s adversary as the symbol of Thebes, and the shrill cries hovered over the land like an eagle, describing the quarrelsome despots of Polynices. The influence of the god, Zeus, and his retribution for the impiety and aggression of the Argive army and Bacchus, who will guide the nights festivities introduce the importance of the intercession of the gods as the play progresses. The tragedy of Antigone’s family history is brought up and becomes a reference in the play. It is suggested that the incestuous nature of her family create her motives for strong family unity. The symbolic view of Antigone’s final marriage to Hades is her imminent death. It is also noticed that she has shown no signs of compassion shown towards Haemon, also in her oikos, and contradicts her self. She states that if her husband or children were left unburied she would not defy Creon. She could always find another Husband and birth other children, but she will never have another brother. Creon is confronted by Teiresias, first to give him advice on the current situation. When Creon denies his advice to free Antigone and bury her brother, and considers it as a bribe. Teiresias then prophesies that because the rejection of his offering by the gods, Creon has obviously upset the divine rulers. Teiresias sees the death of Creon’s own oikos. Creon still stubborn only changes his mind by the persuasion of the chorus. Only until the polis reminds Creon that the prophet has always been trustworthy does he attempt to do the right thing. Unfortunately Creon first buries the brother then goes to free Antigone. He is too late and suffers over the death of his own oikois. The second episode addresses the defiance of the civic law by Antigone, the possible involvement of the gods, the elevation of kinship above civic law, and the residual effects of the Group # 19 house of Oedipus. The unhappy daughter of Oedipus has been singled out after the dust storm has mysteriously faded away to reveal Polynices with a mound of dirt upon him, clearly a defiance Creon’s civic law. To Antigone, there is a divine right to bury the family of the departed relatives and it should take precedence over Creon’s civic law. The two main characters will define the play by their major difference of the interpretation of the law against the predetermined misfortune brought upon Antigone and Ismene from the house of Oedipus. Creon, the uncle of the daughters of Oedipus, is not immune from this misfortune and is reminded by the chorus of this girl’s spirit. Antigone’s emotional appeal to the unwritten rule also brings out the pathos of the situation and the sympathies of the audience. In the third choral song and the third episode, the fate by the gods, the fleeting kinship with Haemon, and the second class status of women are front and center to solidify Creon’s position and adherence to his civil edict. Haemon’s requests to allow for varying views will put Creon’s authoritarian rule in direct contradiction to the Athenian democratic rule and will serve to question the legitimacy of Creon’s rule of the city-state. Creon’s downfall has started with the exodus of Haemon. Sensing his crumbling power, he dismisses Ismene but orders Antigone to be buried alive without burial rites. Ironically, she has suffered the same outcome of her brother, Polynices. Her prayer to Hades will be her only means of escape, thereby absolving him from further pollution of the city. Creon is oblivious to the Chorus’ cries that Haemon’s youthful heart will grow bitter and will soon see his cherished kinship with his son forever broken and beyond repair. “Antigone reveals her immediate motive, which is love” (Richard 76). She obeys a different law that the audiences recognize as most religious. “Antigone suffers what any Group # 20 individual risks who asserts freedom under tyranny, or individualism against pressure to conform. For this act of public heroism, her motive is domestic” (Richard 8). To Antigone, there is a divine right to bury the family of the departed relatives and it should take precedence over Creon’s political law. Antigone acts in defiance towards Creon, because of her outstanding love for her family, and that divine law is given to families by the gods. Antigone undermines Creon’s new power as the king of Thebes by juxtaposing his rules next to that of the god’s rules that looks kindly on the divine law of families to bury their dead soldiers, regardless of circumstances. In this manner she hopes to defy Creon the opportunity to use his perception of Polynices as a traitor to justify his actions for the edict. Antigone also tries to undermine the power of Creon by claiming most of the citizens agree with her but do not speak, not from respect but from fear of the monarchy. “Creon’s laws are his own; the principle behind them is obedience to power” (Richard 8). Creon tries to create stability, and his primary motive is his hunger for more power. Creon’s displays an authoritarian form of leadership. His tyrannical behavior is seen early on when he expects obedience from the elders, issuing an edict with out consulting them, and tells the chorus they should not side with those who disobey these orders. Creon’s emphasis on the importance of the city and obedience of its citizen’s t to its edict sets the background for the proclamation that will deny the traitor, Polynices, burial rites. Creon puts his power above all other types of power. He places human law over divine law. Creon does not want to listen to either Haemon or the chorus and insists upon total obedience form the community of the city of Thebes. Creon’s actions will not only alienate him from his kinship with his son but also increase the allegiance of the citizens to the importance of divine burial rites professed by Antigone. He will refuse to consider the reasonableness of Antigone’s argument of burial to avoid the “scavenging dogs” Group # 21 and will disregard Haemon’s admonition of the citizens who mourn her death and think she deserves to win a golden honor. His authority and credibility as a ruler are questioned because of his adherence to his civil edict and refusal to allow for the enactment of Antigone’s belief in the divine law. Haemon, Creon’s son, is romantically interested in Antigone, while Antigone does not show the same interest towards Haemon. Motivated by love for Antigone, Haemon argues with his father and takes on a “democratic view of law and leadership” (Richard 8). Tiresias, a person admired by Creon in the past, also tries to warn Creon of the displeasure and the power of the gods. According to Aristotle in Poetics tragedy requires several different aspects including plot, character, thought, diction, melody and spectacle. Here we will focus on character, which according to Aristotle must we one that we admire and is good but that has a “flaw-hartia, or some error in judgment” (Lines 2). Aristotle claims that in a tragedy the character “falls from happiness into misery as the play progresses” (Lines 2). Towards the end of the play the character will experience anagnorisis or recognition which is the “change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune” (Aristotle). “Tragedy initially inspires pity for the hero and fear for ourselves” (Ahrensdorf 169). So this means that Antigone, the hero is pitied, for her heroic acts towards the burial rights of her brother. The tragedy also tries to instill fear into the audience by proving a point to stick closer to family and not forget how they are your foundation. “Aristotle claims that the pleasure of all poetry, including tragic poetry, originates in the philosophic pleasure of learning” (Ahrensdorf 169). “Tragedy must draw our attention to the apparent evils of our condition and must thereby arouse our pity and our fear. But it must also, somehow, free us from those passions” (Ahrensdorf 174). Group # 22 Antigone embodies this Artistotelian formula of tragedy. At first glance, one can apply the concept of possessing a flaw in both Creon’s and Ismene’s characters. In the beginning Ismene refuses to help Antigone making her flaw being that she seems “excessively timid”, yet, later she changes her mind and “wishes to stand by her sister’s side in death” (Lines 3). Creon, whose flaw is that he is “excessively harsh” in his judgments, later “softens his hard rule” (Lines 3). Both characters possess a flaw yet both are inherently good in the end of the play. However, as Lines points out, the play is about Antigone, therefore she is the one that must posses the tragic flaw as she is the “noblest and most heroic among all the characters” (Lines 3-4). The tone of the play persuades the readers on the side of Antigone. The readers are drawn to her convictions and her notions of what is ultimately just and right. The audience shares in her grief and in her tragic fate. She is admired for her flaw and it is her flaw which fuels the tragic plot. Antigone is seen as a hero, fighting for what she believes in, even in the face of certain death. Throughout the play, Antigone is steadfast and determined in her resolution. From the beginning when she decides to defy Creon’s orders she knows that she will be punished and yet she is decisive about what actions she will take. She stays confident throughout the play that her actions are justified. She reasons that the law of the gods supersedes that of men. Later in the play, Ismene decides to stand with her sister in death and punishment, yet, Antigone “ignores Ismene’s change of heart: ‘Yes. For you chose to live when I chose death’” (qtd. in Lines 4). Additionally, throughout her actions she never mentions Haemon who she is betrothed to. Haemon, on the other hand is trying fervently to reason with Creon for mercy for Antigone. Antigone refuses to deliberate or accept any help from others and “reveals no tenderness for anyone except those already dead” (Lines 4). She does not accept help from anyone in her family and decides to perform the burial acts on her own. She is steadfast in her decision to the point Group # 23 that neither her own sister nor her future husband can do or say anything to either encourage or discourage her actions. Antigone does not deliberate with others as Creon does nor does she change in resolution that she is just and noble. Creon on the other hand deliberates with Haemon, the chorus, and Teiresias and finally decides to undo his actions. He buries Polyneices and then rushes to the cave to free Antigone only to find that she has already hung herself. Antigone, had she participated in deliberation and consulted the advice and help of others may not have suffered such a fate. If she had asked or accepted help from Ismene or Haemon, together, they may have had a better chance at reasoning with Creon and avoiding such tragic endings. Therefore, Antigone’s flaw is that of “self-certainty” or “self righteousness” (Lines 5). As the chorus says to Antigone, “thy self-willed temper hath wrought thy ruin” (Sophocles). Antigone is self centered and she seems to become more “extreme in her certainty” as the play progresses (Lines 5). Before her death, Antigone explains that only the love of a brother could stir her to such drastic measures and suicide (Haigh 2). “And yet I honoured thee, as the wise will deem, rightly. Never, had been a mother of children, or if a husband had been mouldering in death, would I have taken this task upon me in the city's despite. What law, ye ask, is my warrant for that word? The husband lost, another might have been found, and child from another, to replace the first-born: but, father and mother hidden with Hades, no brother's life could ever bloom for me again” (Sophocles). Antigone basically asserts that neither the love of her husband (which would have been Haemon) nor the love of her future children could have produced such willingness to defy the law when knowing her certain deadly fate. This is her flaw; she is so blind to others that she does not see that her reasoning contradicts her supposed loyalty to her family. Yet, Haemon, Ismene, and even Creon are willing to deliberate and reason with Antigone and she rebukes them all. Creon Group # 24 sees his error and understands that compromise may lead to a less tragic fate. He rushes to try and fix what he has done. Only Antigone, being so self-willed, as already seen to it that she will not wait for anyone, even in her own death. In continuing to follow the Aristotelian formula of tragedy, Antigone also includes anagnorisis or recognition, “a change from ignorance to knowledge”, as stated earlier (Aristotle). Recognition, as Markell suggests, is the “recognition of an identity, either one’s own or another’s” (29). In tragedy one’s identity is founded in one’s actions; simply put “we know what we are to do, at least in some significant part, by knowing who we are” (Markell 3). Both Antigone and Creon struggle for recognition. They both have an identity formed mainly through gender roles that directs their actions. Yet, through the course of the play, they “exceed the terms of identity” that they possess. Meaning that they may possess a certain identity at first, but as their actions progress, their identities change and develop into ones that neither of them could have foreseen. Antigone’s actions are fueled by her identity, which happens to coincide with conventional gender roles. For example, Antigone’s desire to bury Polyneices is spurred by obligations of kinship (Markell 10). When Ismene rejects Antigone’s plans, Antigone responds by “expressing her allegiance to the bonds of the family” (Markell 10). When she performs the burial rites for Polyneices she is also identifying with conventional gender roles. Antigone does not actually bury the body, which is “a task that was generally performed by men”. Instead, Antigone “conforms quite precisely to classical norms governing the role of women in funeral rites” by sprinkling dust and oils over the body (Markell 11). Antigone represents female gender roles and the family (oikos). Creon’s identity is masculine and he represents the city (polis). Creon is committed to the order of the city and the laws. As a new ruler of Thebes, he does not want to make exceptions for the laws that he sets, not even exceptions for the royal family. He is Group # 25 committed to the polis (Markell 12). Creon seems tyrannical at one point when he condemns both Ismene and Antigone to death. He “will never let himself be conquered, ruled, defeated by a woman” (Markell 12). Both Creon’s and Antigone’s identities are what fuel their actions in the play. However, their actions “do not flow smoothly from their identities” (Markell 13). Both characters do more than they both intend and break their conventional gender roles with their actions. Therefore, as Markell suggests, this may not be a case of recognition, but a case of misrecognition (or hamartia) which affects the characters’ own pursuits of recognition. Antigone tries to express her allegiance to her family and loyalty to blood by performing funeral rites for Polyneices. When she does so, her act of family loyalty also turns into an act of political subversion, an act which is inherently masculine. Her own self proclaimed devotion to her family is also questioned when she rejects Ismene, her own sister who offers to share in Antigone’s fate. She refuses help from Ismene, and does not even attempt to ask for any assistance from Haemon. Someone who is so self-proclaimed loyal to the family as Antigone should have used this family loyalty as a tool to reason and convince Creon of his error. Additionally, Antigone refers to the cave in which she is sealed as her “marriage chamber” (qtd. in Markell 15). This shows the reader her hesitancy to accept the gender role. The word chamber has negative connotations and relates to the reader that Antigone viewed marriage similar to imprisonment. All of these actions she does not intend, but they force her into an identity opposite of the one she had previously based her actions upon. Creon’s actions are in defense of the polis. However, these actions turn out to hurt his own family, his oikos. His masculinity is closely tied to him being the ruler, so defiance by a woman is the ultimate assault to his manhood. He is continually attempting to assert his power and authority as the new ruler of Thebes. He does not want to make exceptions for anyone, even members of the royal family. After receiving the prophecy from Teiresias, Group # 26 Creon decides that it is better to follow the laws of the gods in regards to giving Polyneices a proper burial. So Creon attempted to represent the city and human law, but in the end he is compelled by the family and divine law (Markell 28). Sophocles wrote Antigone with the intention of providing a lesson in civic discourse for his audience, the ancient Greeks. Many of the lessons presented in Attic theatre are still relevant with modern readers today. Although today, the analogy of proper burials may be less relevant, the idea of family loyalty and respect still has a stronghold in modern traditions and values. Antigone provides lessons to the audience regarding the need for social order, the consequences of tyranny and the refusal to deliberate, the importance of divine law, family loyalty, and civic disobedience. The play ends in tragedy and the deaths of Antigone, Haemon, and Eurydice can be attributed to the actions of both Antigone and Creon. Antigone was stubborn and refused to see anyone else’s point of view. She never sought help from her future husband Haemon and she ended up refusing Ismene when she ultimately decided to stand by Antigone’s decision in death. Antigone did not participate in deliberation and the end result was that she sealed her own fate. A lesson for the audience would be to not be stubborn and willful but to actively participate in discussing the problem and finding alternate avenues of compromise. Creon’s actions can be seen as acts of tyranny. In the beginning of the play, he declares that no one is to bury Polyneices and that if anyone defies him they will be put to death. As the play progresses and Creon begins to see the consequences of his actions unfold, he realizes that he cannot act in such a tyrannical manner but must discuss the issue with all sides to come to an agreement. He rushes to undo what he had done, only to find that he is too late and his actions have resulted in deadly consequences. During the time the play was being written, the ancient Greeks were experiencing a transition from tyranny to democracy. As Lines claims, “political deliberation requires listening Group # 27 and persuading, engaging, and being engaged” (1). Democracy requires active participation and deliberation as well as compromise. Antigone helps the ancient and modern audience understand the importance of these democratic principles. The “general motive of the play, the conflict between human law and the individual conscience, is one of deep universal significance” (Haigh 1). As the play unfolds, the audience may feel torn as to whether Antigone is guilty for defying human order or whether Creon is guilty for going against divine laws. The resolution of the play, however, reveals Sophocles intention. The tone of the play is favorable towards Antigone and “in favour of the conviction that human ordinances must give way to the divine promptings of the conscience” (Haigh 2). Creon sees his error claims that “reverence for the gods must be preserved inviolate” and that “perhaps it is best to keep the laws of heaven” (qtd. in Haigh 2). This clearly shows that Sophocles intention was to explain to the audience that the laws of the gods should take precedent over those of humans and cities in certain circumstances regarding family, loyalty, and tradition. Antigone can also be viewed as an early example of civil disobedience, the act of peacefully resisting the laws of the government in protest. Modern readers can relate to lessons in civil disobedience. Many “modern day protesters stand up for what they believe is personally right” even though it may be “in direct disagreement with the policies of the current political administration” (Pruyne 2). Antigone exemplifies civil disobedience by disobeying Creon and holding true to her familial responsibilities to bury her brother. Antigone is strong in her will and even though she understands that she will die for her actions, stands by her decision. Modern readers can relate to this act of civil disobedience such as those “who protest the United States current war with Iraq and the past war of Vietnam” (Haigh 2). Finally, Antigone provides a lesson in the importance of keeping family traditions, values, and loyalty. Though Polyneices may have acted as a traitor to Thebes, Antigone realizes that first Group # 28 and foremost he is her brother, her kin, and that she has a duty to treat him with respect in his death by performing common burial rites over his body. She tells Creon that she has performed these rites over other family members and that Polyneices is no different. Ismene also shows that she respects her family. At first, she denies Antigone help only later to realize the importance of loyalty and stand firm against Creon’s law and accepting death as well. Haemon also shows loyalty. He is betrothed to Antigone and defends her actions to Creon. He attempts to reason with Creon not to sentence Antigone to her death and understand the importance of Polyneices’ burial. Towards the end of the play, Creon realizes that his family should have come before his obligations to the city. Once he has lost his wife, son, and future daughter in law he prays for an early death because he discovers that his family is the most important thing to him. Sophocles’ Antigone is relevant today in that it teaches modern readers how to deliberate and reach conclusions. The play is the third play in the trilogy which includes Oedipus Tyrannus, Oedipus at Colonus, and of course Antigone itself. Oedipus Tyrannus teaches the audience the dangers and consequences of making assumptions. Oedipus at Colonus follows in the lesson by showing that instead of assumptions leading to a conclusion, one must gather proper evidence. Finally, Antigone finishes the trilogy and the lesson by teaching the audience that assumptions and evidence can lead to a conclusion, but arriving at the proper one requires deliberation, participation, and compromise. Sophocles structures the play in a way which reveals important aspects of Antigone and Creon’s characters. Their flaws exemplify to the audience what to avoid during a conflict. The overall conflict of human law versus divine law is resolved in the conclusion of the play with the verdict being that divine law should be respected and held true especially over human laws that are unjust and tyrannical. Finally, the concept of recognition in the play displays the conflict of the polis versus the oikos. The importance of the family and Group # 29 keeping to tradition comes before obedience to the city. Antigone is an influential piece of Attic theatre that will continue to teach the audience lessons of civic discourse through its employment of tragic elements and Aristotelian principles.