Chapter 5 Answer for Problem 10.doc

advertisement

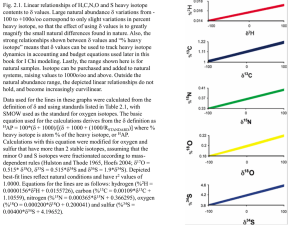

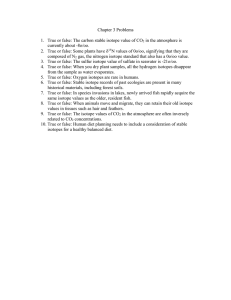

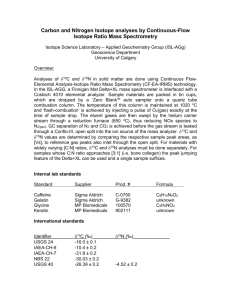

Answers for Problem 10, Chapter 5 Here are the answers for six steps, and graphs showing the details of the work can be found in the appended powerpoint slides. You might want to check out the graphs first, to see if you can get the gist of the progression, and see if your graphs look similar. The complete data table accumulated from all the steps is given in Table A as the starting point of the answers. Table A. Final food web results in tabular form. Trophic level assignments are based on δ15N data. The source assignments, %Corn and %Tree Leaves, were made using the corrected δ13C values, values that had been adjusted for trophic level (TL) 13C fractionation. δ15N TL original δ13C corrected δ13C Tree Leaves 2 Mushroom 3 Worm 4.2 Centipede 8 Spider #1 5 Spider #2 10 Sparrow feather 8.5 Eagle feather 12 Corn 2 Grasshoppers (herbivores) 4.2 1.0 1.3 1.7 3.0 2.0 3.7 3.2 4.3 1.0 1.7 -27.0 -24.0 -26.0 -21.0 -24.0 -21.0 -23.0 -18.0 -13.0 -13.0 -27.0 -24.2 -26.4 -22.0 -24.5 -22.3 -24.1 -19.7 -13.0 -13.4 % Corn 0 20 5 36 18 33 21 52 100 97 % Tree Leaves 100 80 95 64 82 67 79 48 0 3 Step 1. Plotting the raw data. Figures A-D show 4 different ways to plot the data. Many studies start with graphs that look like Figures. A and B. Figure A is not good because the current convention is to use the carbon isotope data on the x-axis and the nitrogen isotope data on the y-axis. One advantage of this convention is that higher 15N values along the y-axis indicate higher trophic levels at higher positions in the graph, an intuitive result. Figure B is not good because the symbols on the axes aren’t properly labeled. Figure C is good, but the carbon units are given more weight than the nitrogen units (i.e., 1o/oo in N units on the y-axis is only half as big as 1 o/oo in C units on the x-axis). Figure D is probably best, giving the C and N units the same weight. (Note: Make sure your axes are labeled correctly. With a word processing program, you can find the “” symbol used in labeling the graph axes, by typing the letter “d”, highlighting it, then changing the font to “symbol” - the greek letter “” should appear. Also, be sure to use a superscript for the 13 and 15 in 13C and 15N). Overall, these initial data do show an increase in 15N expected when several TLs are involved, and birds have the highest 15N values as expected for top predators. The data shows a positive correlation between 13C and 15N, which would support the interpretation that both 13C and 15N increase with increasing TL. Step 2. Interpret your plot – trophic levels. The TL increases are usually much larger for 15N than 13C, 4-6 times larger. The actual o/oo increases per trophic level are estimated at 2.2 -3.4o/oo for 15N and 0-1o/oo for 13C, or average values of about 3 and 0.5o/oo respectively. Ecologists generally trust the 15N-based estimates of TL because of the much stronger TL signal in the N isotopes than in the C isotopes. Also, source mixing effects are usually much larger than TL effects for C than for N isotopes, so much so that TL effects in the carbon data are obscured by source mixing. Using the 15N data, the plant value at TL1 at the base of the food web is 2o/oo, and counting upwards from that value with an increment of 3o/oo equaling one TL, the highest calculated trophic level is 4.3 for the eagle. Using the formula TL = 1 + (15NCONSUMER - 15NPLANT)/3 gives discrete estimates of TL for each sample (see data in Table A). There is one sample, spider #1, whose TL seems too low at TL2, the herbivore level. Most spiders are carnivores - you would have to check the species of this spider to see if it is really known to be herbivorous. Step 3. Interpret your plot – sources and 13C. There is a problem with the 13C data, and here it is: If the animal data represent about 3.3 trophic levels above the plant base, and 13C increases 0.5o/oo per TL, then the total 13C increase from the -27o/oo leaves at the base of the food web should be 3.3 x 0.5o/oo =1.65o/oo, or -27o/oo + 1.65o/oo = 25.35o/oo. This should be the value for the eagle, but we don’t get that value. Instead we get the much higher value of -18o/oo. We have much too much 13C enrichment, and the data look like a stairway that never quits rising (Fig. D). In fact, this turned out to be a rather typical problem for isotope food web research. When we asked a more experienced colleague about this result, we heard that we might consider “inferring” another source to be present that had a much higher (less negative) 13C value. To check this inference, we went back to the forest site of the original sample collections. Nearby, we saw many cornfields which we realized also might have provided food prey for the birds. So we collected corn plus grasshoppers. After this nice day in the sun, we returned to the laboratory where we dried and ground the samples, then sent them off for analysis. After a few weeks, the results come back as these respective 15N and13C values: corn 2o/oo and -13o/oo, and grasshoppers 4.2o/oo and -13o/oo. When we add these data, we see the “mixing arch” typical of 2-source food webs (Fig. E), with sources at either end. Values for predators plot in the top middle, appropriate since they are the highest TL and integrate all the source inputs from both sides of the 13C spectrum (Fig. E). With the new data, the increase in 13C at higher TLs noted above in step 1 can now be re-interpreted in terms of source mixing, but there may still be a component of TL that needs to be factored out of the 13C interpretations (see next step). Generally tree leaves seem the most important food resource, but there are also strong (>20%) contributions from corn for many consumers. Step 4. 13C-based source assignments revisited and refined. Generally, sample 13C values increase with increasing trophic level, because of incorporation of 13C-enriched materials from the diet and isotope fractionation during metabolism (Fry and Sherr 1984, Fry et al. 1984). Here we are interested in source contributions, so we first factor out effects of fractionation by subtracting 0.5o/oo for each trophic level above plants. Fractionation-related 13C corrections are sometimes made for lipid bias in food web studies, but these further corrections are not included in this simple example. Applying the trophic level corrections generally shifts the 13C data points towards more negative values (Table A), indicating a stronger influence from tree leaves and any other foods that share the -27o/oo carbon isotope value of tree leaves. When we revisited the study site and collected corn, we noted some streams in the mixed forestcorn landscape, and stream algae can have these same -27o/oo 13C values. Step 5. Calculate source contributions from corrected 13C values. This is straightforward from the formula given in step 5 of the problem, and results are given in the Table A. The tree leaf contributions increase slightly as a result of these corrections that shift 13C values in a negative directions, towards the values of the tree leaves. Step 6. Summary. We have worked through an example of how to interpret isotope data for a food web, plotting the measured 15N and 13C values in a nicely-thought out graph (Fig. E). We then recast our interpretation of this data in a second similar-but-notidentical graph in terms of trophic level and source contributions (Fig. F). The overall results show 4.3 trophic levels and substantial influence of corn in this agricultural landscape. We used %corn and TL as the respective x-axis and y-axis to preserve the parallelism with the original 13C and15N data. So, what have we learned beyond the mechanics of how to graph up the data? Most importantly, we obtained the outlines of a food web with really very little effort overall. Many animals spend >50% of their time in food-related activities, so focusing on food webs is an important aspect of community ecology. Also, the food web integrates many processes occurring across the landscape, drawing from both agricultural corn fields and natural forests. Studying isotopes in food webs shows landscape and ecosystem level connections. Lastly, it was interesting to use bird feathers – more and more bird species are endangered, and it is good to have non-lethal samples such as feathers to help indicate feeding habits and basic bird ecology. One extra effort we made during this study was revisiting the field site and sampling corn, finding a “missing link” or food source that we inferred must be there. This inference and extra sampling is very often the case, because it is not always possible to guess which foods are really most important sources in food webs. There were also some puzzles in the data. For example, what kind of spider is it that would be at trophic level 3.7, and is the mushroom in Table A really relying on 20% corn? Some field work and literature review would be well-advised to help solve these puzzles. Really, it is often better to start with a quick isotope diagram, then dig into the actual food web with other eco-observations such as watching with binoculars, performing lab experiments or examining gut contents under a microscope. This longer eco-effort is usually needed to see the details of how the food web really fits together under the isotope rainbow. Isotopes are just part of the picture, but especially good for getting the overall picture straight in your mind, even if what’s actually happening in this food web picture needs a lot more scrutiny to discern the details. You might also think about your isotope results from two points of view. One viewpoint identifies patterns in the overall distribution of isotopes you see when looking at biplots of C vs. N isotopes. Multivariate statistics can help bring out the contrasts in these distributions (Litvin and Weinstein 2004). Using patterns you can discuss whether isotopes in one area/watershed/food web are different than in another area. This is a classification problem, focusing on the differences between food webs. If there is a reference area or food web, then this classification helps you see difference/divergence from the reference, and is a strong use of isotopes (Moseman et al. 2004). The second viewpoint is emphasized in the example above, calculating source contributions. However, it is common to have too many sources and not enough tracers, so that in the end, the source calculations become less exact minimum-maximum (“minmax”) estimates. Point F below outlines this problem in detail. Calculating source contributions is actually most useful in a negative sense, i.e., for identifying which sources are unimportant. But when considered together, the positive identification of strong patterns in the data (viewpoint 1 above) plus the negative rejection of unimportant sources (viewpoint 2 above) make isotope analysis a powerful approach for investigating food webs. Lastly, there are several practical complications that often arise while working with these isotope food web diagrams. Some common problems (A-F) are listed below, along with some references and advice that will help you work through these complications. A) In these isotope diagrams, there are fractionation adjustments for trophic level that apply to both N and C isotope data. The respective trophic enrichment factors of 3o/oo and 0.5o/oo for N and C isotope data used in this example are general averages, and may be different for the animals or systems of most interest to you. You may want to consult three references (Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001, Post 2002, McCutchan et al. 2003) for more detail about the trophic level enrichment factors that are needed for interpreting these isotope diagrams, e.g., you may want to consider the effects of using enrichment factors of 0.0o/oo instead of 0.5o/oo for 13C and 2.2o/oo or 3.4o/oo instead of 3o/oo for 15N. B) Before making the source interpretations in step 4 of this example, also you may need to consider other corrections. For example, you may want to add about 1o/oo to 13C values if samples have been preserved in formalin (Sarakinos et al. 2002), and add 0.5-3o/oo to 13C values for samples with high lipid contents, as determined by lipidextraction (Hobson et al. 1995) or C/N-based calculations (Fry 2002). However, if these corrections are small for your samples, it may be better to not make the corrections, for each correction you make also introduces another source of error. C) The terrestrial example of this Appendix above has very few samples – just a handful. How many more samples would really be enough in a food web study, and with more samples, how can we estimate errors in the assignments of trophic level and source contributions? (for help, see: Phillips 2001, Phillips and Gregg 2001, Phillips and Koch 2002). D) Basal plant food resources often have different 15N values so that determining the baseline value for trophic level 1 is not straightforward, complicating estimates of trophic levels for consumers. Many TL estimates start at the herbivore rather than plants, because plants vary too much or because the exact plant base is not always known. Herbivores integrate and average out this variability present at the plant level (for help, see: Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001, Post 2002). If you use an herbivore, the equation for trophic levels starts counting at TL2 instead of TL1 and becomes: TL = 2 + (15NCONSUMER - 15NHERBIVORE)/3 Also,13C values are sometimes used to help understand and model variations in the15N baseline (Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001, Post 2002). E) How do we recognize animals from a different region, animals that are migrants or transients, versus the residents that belong with the food resources being sampled locally? (for help, see: Caccamise et al. 2000, Fry et al. 2003). F) There are not just 2 plant food resources in many food webs, but 3-10 potentially important plant foods. In these more complex cases, it is not clear which foods support consumers, and only potential minmax contributions can be calculated for the food resources (for help, see: Phillips and Gregg 2003). To illustrate these minmax solutions, here is an example problem with too many sources (3 sources) and not enough tracers (1 tracer). Given three sources with 15N values of 5, 10 and 15o/oo, what are the source contributions to a sample whose isotope value is 10o/oo? The models return the answer that on average, each source contributes an equal one third to the sample. But inspection quickly shows that there are in fact an infinite number of potential or feasible solutions to this problem, with percent contributions of sources 1,2, and 3 feasibly (0,100,0), (50,0,50), (25,50,25), etc. No solution is intrinsically more correct than the next one, and a model-reported average value is just one more virtual estimate with equal standing to all the other feasible solutions. In this case, a better viewpoint than emphasizing averages is that the data provides a set of minmax estimates for each source. In this 3 source example, these minmax estimates are 0-50% for source 1, 0-100% for source 2, and 0-50% for source 3. Such min-max estimates reflect the true level of constraint provided by the data, without an incorrect (but tempting) extrapolation to a unique solution. To address this common problem of too many sources, Phillips and Gregg developed IsoSource programming available on the web at http://www.epa.gov/wed/pages/models/isosource/isosource.html. This programming calculates contributions from multiple sources, typically starting from (13C, 15N) data. Note that this web-based approach arose after Phillips (2001) discredited a published intuitive approach to interpreting source contributions. The intuitive approach was based on proximity of the sample isotope value to those of various sources when samples and sources are plotted in a diagram of 15N vs. 13C (Ben-David and Schell 2001). But sources far away from samples in these multi-source isotope diagrams can also contribute strongly, so that this intuitive “near = important” model is flawed when many sources are involved. Instead, mixing models should be based on mass balance principles outlined in Section 5.4 of this book. There are four important steps you need to think about when dealing with the minmax IsoSource programming of Phillips and Gregg (2003). 1) Your goal is to estimate source contributions, so the first step is to factor out any fractionation that may be occurring. For example, for a carnivore whose 15N value is 6o/oo, subtract 3o/oo to correct for fractionation to the herbivore level, and a further 3o/oo to get to the original plant source level, 0o/oo. Similar steps apply for any carbon fractionations. For food web diagrams using (13C, 15N) data, you may want to rely on general ecological estimates of trophic level when making your corrections, without using 15N to estimate trophic level. Why not use 15N in these (13C, 15N) problems? Because the 15N estimates of trophic level generally assume a starting source value, and it would be circular reasoning to work forwards from the source 15N to estimate trophic level, then work backwards from that value to re-estimate the source 15N. So, you need to find another way to estimate trophic level if you want to use 15N as a source indicator, and general estimates from feeding observations such as stomach content data may suffice. 2) Plot your fractionation-corrected consumer isotope data along with your source plant data in 13C vs. 15N biplots. Does the corrected consumer data fall within a polygon you can make by connecting the points for the source plants? If not, you may be missing a source. Collect more samples and consult the literature to see if you can add a source point in the right place so that the polygon encloses all the consumer data. 3) When dealing with too many sources in isotope mixing diagrams, researchers commonly face a decision about aggregating sources, whether to “lump” or “split” sources. The usual case is that there are many, many food resources in nature, so the researcher must make some decisions about what is important and what is not. Mathematically, it is very useful to lump and aggregate sources, because with fewer sources, often one can obtain exact solutions for the contributions of each source. But if the number of sources exceeds 3 in your (13C, 15N) biplot, then only minmax estimates can be obtained for the source contributions. This minmax information is often much less conclusive. There are five strategies to help work on this common problem of narrowing down too many sources to just a few sources, using the IsoSource programming of Phillips and Gregg (2003): i) Plot all the isotope data for the potential sources, and use the visual plot to aggregate sources that have similar isotope values. In effect, nature has pre-aggregated these sources anyway in terms of isotope mixing diagrams. ii) Is it possible to aggregate foods by region, so that the food problem becomes a geographical one? Often the net food resource in one area is quite different and distinct from that in another area, so that that you can use aggregated “regional averages” rather than considering all the individual foods themselves. iii) Use the minmax IsoSource programming to calculate source contributions, and see if any source has typically small contributions and can be ignored and dropped from consideration. iv) Is there any other non-isotope information such as stomach content data that can constrain the source contributions? Constraining any one of the source contributions will often remarkably shrink the minmax ranges of all sources towards exact solutions. v) Lastly, realize that no matter how you calculate the source contributions, exactly or as minmax estimates, that both sets of estimates share an important similarity. This similarity is that all the estimates let you exclude certain sources as unimportant. This is science at work, excluding and falsifying hypothetical source contributions. However, when trying to support (but still not prove) the importance of certain food resources, it is preferable to have the exact estimates or minmax estimates that have narrow ranges. You will have to work this out for yourself, balancing your desire for exactness against your biological assessment of how many foods are likely to be important. 4) Once you have the source contributions, you can use a bar graph to think about the minmax results (Fig. G). But how should you really think about these kinds of minmax data? You will have to decide for yourself what is important and how to present it, but here is some of the logic. a) A low maximum value means you identify the food source as unimportant (this is a strong use of isotopes, so perhaps you should just plot maximum values, Fig. H). b) High maximum values are not very useful. c) Low minimum values are not very useful. d) A high minimum value is useful, and supports or “is consistent with” an important role for that food and is a fairly strong use of isotopes. For this reason, you may choose to plot the minimum values (Fig. I). But high minimum values still do not prove the importance of the food, especially since other unmeasured foods may have been missed in the analysis. e) Large ranges between minmax estimates are often not informative, unless the minimum is high (see previous point d). f) Small minmax ranges are informative, narrowing towards exact values (but see also caveat for point d). g) Working through the steps above, you may find that you can rank the importance of sources from the minmax estimates, even if you cannot solve for average contributions. It is interesting that these steps for estimating source contributions apply not only to food web isotope studies, but also much more widely. For example, the steps of correcting for fractionation and aggregating sources figured prominently in a study that estimated sources of atmospheric methane from isotope data (Snover et al. 2000). In summary, working with isotope mixing diagrams takes some practice and has some complications that need to be considered. Errors accumulate from several steps, and it is good to try to keep these errors in mind when making final interpretations. Several models help work through food web isotope problems (Phillips and Gregg 2003, HallAspland et al. 2004, Lebetkin and Simenstad 2004), but usually the data only support minmax conclusions. So the closing advice is this. Use the models to look at a range of feasible minmax solutions, and try to discern the common features of those solutions (Benstead et al., in press). Those common features should be there because they are supported by the data. Find those features and report those features. Further Reading: Caccamise, D.F., L.M. Reed, P.M. Castelli, S. Wainright and T.C. Nichols. 2000. Distinguishing migratory and resident Canada geese using stable isotope analysis. Journal of Wildlife Management 64:1084-1091. Ben-David, M. and D.M. Schell. 2001. Mixing models in analyses of diet using multiple stable isotopes: a response. Oecologia 127:180-184. Benstead, J.P., J.G. March, B. Fry, K.C. Ewel and C.M. Pringle. In press. Trophic support of inshore fisheries on a Pacific island: testing IsoSource in a multiple-source stable isotope analysis. Ecology. Finlay, J.C., S. Khandwala, and M.E. Power. 2002. Spatial scales of carbon flow in a river food web. Ecology 83:1845-1859. Fry, B. 1991. Stable isotope diagrams of freshwater food webs. Ecology 72:2293-2297. Fry, B. 2002. Stable isotopic indicators of habitat use by Mississippi River fish. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 21:676-685. Fry, B., and E. Sherr. 1984. 13C measurements as indicators of carbon flow in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Contributions in Marine Science 27:13-47. Fry, B., R.K. Andersen, L. Entzeroth, J.L. Bird and P.L. Parker. 1984. 13C enrichment and oceanic food web structure in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Contributions in Marine Science 27:49-63. Fry, B., D. Baltz, M. Benfield, J. Fleeger, A. Gace, H.A. Haas, and Z. Quinones. 2003. Chemical indicators of movement and residency for brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztecus) in coastal Louisiana marshscapes. Estuaries 26:82-97. Hall-Aspland, S.A., A.P. Hall and T.L. Rogers. 2004. A new approach to the solution of the linear mixing model for a single isotope: application to the case of an opportunistic predator. Oecologia DOI:10.1007/s00442-004-1783-0. Hobson, K.A. and R.G. Clark. 1992. Assessing avian diets using stable isotopes II: factors influencing diet-tissue fractionation. The Condor 94:189-197. Hobson, K.A., W.G. Ambrose Jr., and P.E. Renaud. 1995. Sources of primary production, benthic-pelagic coupling, and trophic relationships within the Northeast Water Polynya: insights from 13C and 15N analysis. Marine Ecology Progress Series 128:1-10. Litvin, S.Y. and M.P. Weinstein. 2004. Multivariate analysis of stable-isotope ratios to infer movements and utilization of estuarine organic matter by juvenile weakfish (Cynoscion regalis). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 61:1851-1861. Lubetkin, S.C. and C.A. Simenstad. 2004. Multi-source mixing models to quantify food web sources and pathways. Journal of Applied Ecology 41:996-1008. McCutchan, J.H. Jr., W.M. Lewis Jr., C. Kendall and C.C. McGrath. 2003. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos 102:378-390. Moseman S.M., L.A. Levin, C. Currin, and C. Forder. 2004. Colonization, succession, and nutrition of macrobenthic assemblages in a restored wetland at Tijuana Estuary, California. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 60: 755-770. Phillips D.L. 2001. Mixing models in analyses of diet using multiple stable isotopes: a critique. Oecologia 127:166-170. Phillips D.L. and J.W. Gregg. 2001. Uncertainty in source partitioning using stable isotopes. Oecologia 127:171-179 (see also erratum, Oecologia 128: 204) Phillips D.L. and P.L. Koch. 2002. Incorporating concentration dependence in stable isotope mixing models. Oecologia 130:114-125. Phillips D.L. and J.W. Gregg. 2003 Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too many sources. Oecologia 136:261-269. Post, D.M. 2002. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods and assumptions. Ecology 83:703-718. Sarakinos, H. C., M. L. Johnson and M. J. Vander Zanden. 2002. A synthesis of tissuepreservation effects on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope signatures. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80: 381-387. Snover, A.K., P.D. Quay, and W.M. Hao. 2000. The D/H content of methane emitted from biomass burning. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 14:11-24. Vander Zanden, J.M. and J.B. Rasmussen. Variation in15N and 13C trophic fractionation: implications for aquatic food web studies. Limnology and Oceanography 46:2061-2066. Figure Legends Fig. A. Preliminary isotope biplot, a common starting point in the graphic analysis of stable isotope data. Fig. B. As previous figure, but with carbon data on the x-axis, as per modern convention. Fig. C. As previous figure, but with symbols now correctly given, including superscripts. Fig. D. As previous figure, but the o/oo units on the x and y axes are now similar (i.e., spacing for a 1 o/oo interval on the x-axis equals the spacing for 1 o/oo on the y-axis). Fig. E. As previous figure, but with added data from the second round of sampling. Fig. F. As previous figure, but with axes relabeled to show interpretation of 13C results in terms of sources (x-axis) and interpretation of 15N results in terms of trophic level (yaxis). Fig. G. Minimum and maximum (“minmax”) contributions for a five-source mixing problem in which there are too many sources and not enough tracers. There is no unique average solution in these common cases, only min-max range estimates for each source. Fig. H. As previous figure, but only maximum contributions. Fig. I. As previous figure, but only minimum contributions. Do you have what it takes to become an isotope sourcerer?