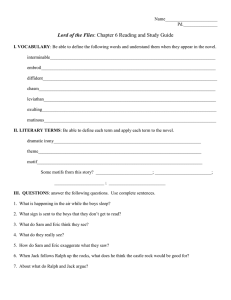

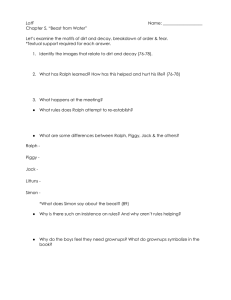

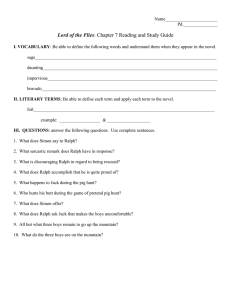

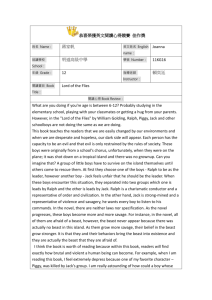

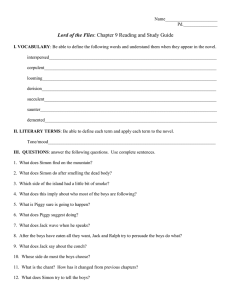

Final test study guide

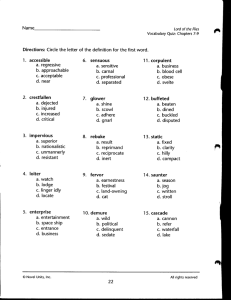

advertisement