Emerging and Persistent Issues for First-year Students

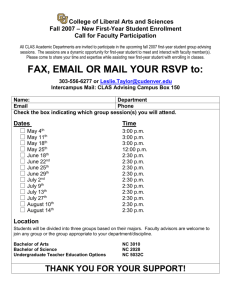

advertisement

Emerging and Persistent Issues for First-Year Students Graham B. Spanier, President, The Pennsylvania State University Editor's Note: This article is based on a speech presented by Dr. Spanier at the third annual Professional Development Conference on Academic Advising held at Penn State's University Park campus in September, 2004. The theme of the conference, sponsored by Penn State's Division of Undergraduate Studies, was “What Generation Are We Advising? Facilitating a Successful Transition to College.” I am pleased to be here with all of you today, because as president of one of America's largest and most complex universities, I am deeply committed to higher education's mission to help students become educated members of society. I know that much of what I will say involves issues you are already well aware of in your daily work. Helping first-year students transition to college and aiding them throughout their college career is vital to their ultimate success as a college graduate. Today, more students are choosing to go to college than at any time in our history. Across the nation, more than 16 million students are enrolled in public and private two- and four-year institutions. While those of us in higher education know that a college experience contributes greatly to human development, cultural advancement, and the quality of life for so many, the reality is that today, for so many, the decision to go to college is largely based on economics. In a recent report, 87 percent of Americans said they believed that a college education has become as important as a high school diploma used to be. In another study by the American Council on Education, a full 94 percent of respondents said that the “right education and training” was an important factor in individual success. From a strictly economic viewpoint, which is how many of our students see their college years, lifetime earning power of an individual increases substantially with each academic degree earned—roughly $1 million more with a baccalaureate degree. This brings me to an important point about today's college students—they are consumers who all too often view education as a commodity. More and more students are turning to rankings, such as those produced by U.S. News and World Report and the Princeton Review, to help make their college decisions. There is also a growing appeal in earlydecision programs. Intense competition among students to be admitted to college has resulted in more firstyear students than ever attending a college that is their second or lower choice. Combined with rising tuition, this competition is driving high-level expectations among today's students. Incoming students want personal attention, a seamless administrative system, specialized housing and food service options, easy access to the Internet, their own bathrooms, microwaves in their rooms, and intense counseling support, to name just a few amenities. They want top-notch recreational facilities, smaller classes, and what seems like on-demand contact with counselors, advisers, faculty, and administrators. It appears sometimes that their parents want even more. Today's students are reported to be closer to their parents than any generation since before the 1960s. These parents appear to be overly engaged in their children's lives, and someone in the popular press has dubbed them “helicopter parents.” For those who don't quite catch the metaphor, these are parents who “hover”—a lot. I have received letters from some of these parents, who intervene on behalf of their children to demand a grade change, push for curfews, ask me to settle roommate disputes, or even to allow drinking in the fraternities. One mother chastised us for not teaching her son to make his bed. In advising, I know you see this phenomenon as early as summer registration when parents, often recounting their own college experiences, tell their children not to take late Friday classes so they can come home on weekends or suggest they forego a chemistry class because it may be too difficult. They convince their children that fewer credits—or more credits—would be a better option, and they may frown on courses that they don't think provide enough marketable real-world skills. I heard of one parent who refused to pay tuition for his daughter to go to college and take “gym classes.” She wanted to be an athletic trainer or physical education instructor, but her father just couldn't get past the notion of paying thousands of dollars a year for his daughter to run track, play tennis, or swim, even if that is only a tiny portion of the courses outlined for that major. Students navigating the newness of college used to turn to advisers, who acknowledged their struggles, discussed concerns, and prodded them to think independently and take responsibility for their own learning. Many students now appear to be turning to parents for solutions. As you know, the answers are not always best, and often you end up advising parents and their children. As advisers, you are working hard to teach students how to take control of their own lives, how to think more broadly, explore possibilities, and develop learning and life management skills. There is no doubt that your job is becoming more challenging as you deal with these new attitudinal shifts and a host of other changes. Let me quickly tell you a little bit more about the students we are serving, because there is a wide range of research on those born after 1982, sometimes referred to as the Millennial Generation. Just a bit of trivia first—in the very near future you are likely to deal with a large contingent of male students named Michael, Jason, or Christopher and a host of female advisees named Jessica, Jennifer, and Ashley. These are the most common names for this generation. Despite the repetition of names, however, these students will be the most diverse that we have ever seen, not just in ethnic and racial makeup, but in other characteristics as well. They may be older, only attend part-time, and are likely to hold a job. In fact, nontraditional students dominate undergraduate enrollments nationally today. All of these characteristics are having a tremendous impact on the advising role. For example, working students come with their own set of challenges, among them the challenge of persisting in college as well as taking longer to earn their degree. Easing these students' transition to college may not be as cut-and-dried as in the past and may require more time and more effort on our part to help these students adjust. They may need more individualized attention or our office hours may need to be changed to match their schedules. At Penn State, we have already instituted a number of online services to accommodate this technology-savvy generation who want instant access. Online advances at Penn State include new Web-based placement testing and educational planning, admissions information, advising-related materials, and the ability to check academic progress and grades. We need to continue to think of more ways technology can be used to help first-year students improve their academic performance. Demographics are also affecting how we operate. In Pennsylvania, we have already experienced a dramatic decline in the number of high school graduates across the state. Competition for in-state students has heated up, and institutions are investing more in out-of-state recruitment. In addition, national demographic projections suggest that about 65 percent of the growth in population through the year 2020 will be in ethnic minority groups, particularly Hispanics and Asian populations. But this population change will not be uniformly distributed across the country. Pennsylvania will remain predominantly white, although certain Penn State campuses in various areas of the state are predicted to see a significant rise in minority applicants. These special populations may require more from the advising relationship, particularly for those who find themselves on a predominantly white campus. Because of their distinctive position on campus, some of these students may be reluctant to ask for help. This hesitancy can contribute to academic difficulty and cause students to leave college. Meaningful contact with faculty members and advisers can make the difference. Advisers who view students as individuals can encourage them to see their distinction on campus as a positive force. Research evidence suggests that for first-year minority students, academic advising can be especially important. Advisers can meet critical needs by encouraging a positive self-concept, helping them get involved in the community, and by introducing them to student support services and other resources. Studies have shown that minority students with low expectations and vague or unfocused plans are likely to leave school. It is our job to do everything we can to encourage them to persist. As with many new students who are far from home, finding a support system is critical to college survival. The culture of many ethnic groups is to maintain close family relationships. These students often find leaving home and adjusting to college more difficult than do majority students. Minority students are often able to persist in college because of their positive expectations and interactions with advisers and others within the campus community. As you know, academic performance is strongly related to satisfaction with college, high levels of campus participation, and constructive and encouraging relationships with faculty and other role models. At my annual convocation for first-year students held at the start of each academic year, I urge them to become well-acquainted with at least one faculty member. I also tell them that their academic progress is their responsibility and that they should plan ahead and seek the advice of advisers. Occasionally, I have heard back from former first-year students who tell me that those words of advice were some of the best they had received in their transitional year. In the area of family structure, there are a number of demographic shifts that have impacted our students as well, affecting everything from their access to college to the financial aid they need to additional student services that must be provided. Students are arriving at the University with a broader array of personal and familial challenges. Their demands on our health care facilities and our counseling services, for example, have increased dramatically. Campus mental health facilities are treating a record number of college students, who are grappling with everything from anxiety disorders to depression. A national survey of counseling directors reported that about 18 to 20 percent of students who sought counseling were already on medication. At the University Park campus of Penn State, the number of students seeking assistance from our counseling staff has more than doubled since the 1980s, rising from 900 students per year to more than 2,000 today. All Penn State campuses now have some form of counseling available for students. The rise in mental health problems means changes in other areas of our University, including advising. Possibly, it's a student's academic choices, living situation, or study skills that may be leading to more stress. Students must be our top priority, and this is why I advocate being a student-centered university. As a learning community, we must put our students and their development at the heart of all we do. Here at Penn State, I am pleased to say that we are investing heavily in that idea. Students today are demanding more upscale living accommodations, more recreational facilities, and more student space. We are accomplishing this with new student unions, new libraries, and new multi-sports facilities that grace a number of our campuses. Both the physical layout and the programming in our residence halls are changing. As an example, this semester at University Park we opened the Eastview Terrace complex for junior and senior students. This new cluster of seven residence halls is outstanding. The complex contains single rooms with attached baths, lots of common space, shared kitchen areas, microwaves and refrigerators in the rooms, and a shared laundry facility on every floor. We continue to introduce more academic programs into the residence halls, ask faculty to eat in the dining halls, and bring academic advising to our students where they live. Longstanding data indicate that the residence hall experience is conducive to retention, especially for first-year students who benefit greatly from joining a community of scholars. In this community, they can model and observe appropriate study habits, as well as learn critical time management skills. I mentioned my annual convocation for first-year students. This is my chance to welcome them to our learning community and tell them of expectations and opportunities. In addition to advice on finding role models and taking responsibility, I also counsel them to avoid high-risk drinking and drug use. Nearly half of all high school seniors say they have experimented with marijuana at least once before graduation, and our own data have shown that within their first week at Penn State, many of our students participate in high-risk drinking. Many become heavy users of alcohol. As many as 7 percent drop out for reasons related to drinking. At Penn State, we have attempted to curb this dangerous behavior by providing alternative late-night programming, additional educational programs, intensive marketing campaigns, and by working with community members and the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. As you can see, upon arriving at our doorstep, first-year students encounter a host of difficulties, but they also bring with them a number of new challenges. In 2001, the Manhattan Institute reported that only one in three high school students was minimally prepared for the rigors of college. Retaining academically underprepared firstyear students presents a special challenge for advisers, particularly since the numbers appear to be increasing. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the proportion of students who spend an average of one year in remediation has gone from 28 percent in 1995 to 35 percent in 2000. Students who are underprepared lack basic skills in writing, computation, language, time management, and study habits, and not all advising practices will be successful for all academically deficient students. However, research has shown that a trusting studentadviser relationship is a vital step toward helping them gain confidence and the skills necessary to continue. One proactive measure we could take to ease the transition to college involves a collaborative effort with secondary education. Universities need to clearly articulate expectations and then engage in a partnership so that each party understands the culture of the other. One example is faculty exchange programs with high schools. First-year students are in transition, struggling with choices, responsibilities, and maturation. We need to foster a sense of connection and check for signs of trouble. Being aware of the needs of our students is a first step to reducing attrition. As academic advisers, you can help them develop a sense of belonging and see the university community as inclusive. Your role is to help them discover a suitable identity as a student. As academic advisers, you are playing a key role in our transformation to a more studentcentered university. About the Author Graham B. Spanier is president of the Pennsylvania State University. He can be reached at president@psu.edu. http://www.psu.edu/dus/mentor/041022gs.htm