12646916_manuscript ccc.docx (176.1Kb)

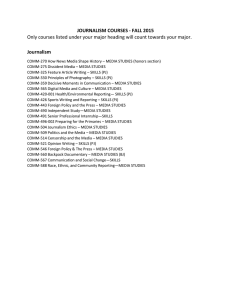

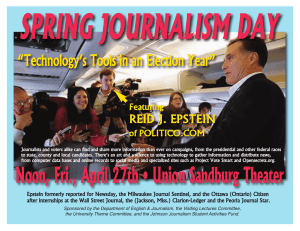

advertisement

CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 1 Culture as Constitutive: An exploration of audience and journalist perceptions of journalism in Samoa Abstract Much research implicitly suggests that journalism values arise from culturally removed organizational structures or shared occupational training and few studies examine the perspective of journalism from both audiences and journalists. These omissions are important given the essentiality of mutually constructed and culturally embedded normative behaviours within journalism. This research examines audiences and journalists in Samoa, a recently independent, post-colonial, country that relies upon a very traditional, shared national identity for its relatively nascent cohesion. This study aims to gain a better understanding of how local culture can set parameters and expectations for journalism; how journalists negotiate culture into their own professional ideology; and how audiences understand journalism within a cultural context. Key Words Culture, Journalism, Audience, Journalist, Hierarchy of Influences Model CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 2 Culture as Constitutive: An exploration of audience and journalist perceptions of journalism in Samoa Journalism, as a social institution, is perpetually constructed and concomitantly deconstructed in concert with local communities who support and engage journalists within a larger collective narrative detailing what journalism means. Journalists construct their own professional identity in large part as a response to audience conceptions of journalism through a process of “collective journalist sense making” (Tsfati, Meyers, & Peri, 2006, p. 154). This process relies upon shared symbolic and cultural narratives in creating an ideology of journalism as an interpretive social institution. Despite this intrinsically communal interconnection, relatively few research studies have explored both audience and journalist perceptions of journalism in tandem. Further, scant research has explored the ideology of journalism within a specific cultural context, and fewer still have fully considered how culture is interwoven throughout audience and journalist perceptions of journalism and journalistic practice. Indeed, culture has been largely removed from theoretical discussions exploring the hierarchy of influences on journalism. These omissions are important oversights given the essentiality of mutually constructed and culturally embedded normative behaviours within the social institution of journalism. In theorizing the identity of journalism, Bogaerts (2011) has said that academics and professionals need to be asking “how journalists negotiate the core values of their profession despite their often problematic nature” (p. 404), rather than labelling journalism as selfevidentiary or critiquing journalism practice as strategic (Tuchman, 1978). Yet, the process of negotiating core journalistic values presupposes that these values already rather spontaneously exist within a somehow culturally removed organizational structure or occupational training. Tensions between the values and practice of journalism are largely relieved by the resignification of learned, institutional journalism routines derived from a common professional training background (Reese, 1990). Through the enactment of institutionalized journalism rituals 2 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 3 and routines, it has been said that journalists can “bridge the inevitable gap between occupational ideals and their practical effectuation” (Bogaerts, 2011, p. 403). The shared thread between these theoretical studies of newsroom phenomenology is an assumption of institutionalized normative behaviours derived from shared professional training and collective knowledge of ‘how journalism is done.’ In so doing, these studies do not address the cultural context of those journalists nor the audience. This widely held theoretical perspective of journalistic negotiation, or what has been labelled ‘news repair’ (Reese, 1990), does not consider that professional knowledge might be subsumed under an encompassing cultural awareness and that the performance of a journalist’s identity may operate at a level fundamentally subservient to the performance of culture. As such, culture may operate as the enveloping influence on journalism above the ideological level put forth in the seminal work of Reese and Shoemaker (1990). Journalism might therefore be best understood within its cultural context and not through a professionalised, normative lens, which examines journalism outside of culture’s reach. This research provides analysis of interviews and focus groups with audiences and journalists in Samoa, which is a recently independent, post-colonial, country that relies upon a very traditional, shared national identity for its relatively nascent cohesion. Samoa has had historical tensions in press freedoms and is still very much in the midst of formally and informally creating a shared understanding of what journalism is and should be within its borders. This study aims to gain a better understanding of how local culture can set parameters and expectations for journalism; how journalists negotiate culture into their own professional ideology; and how audiences understand journalism within a cultural context. In so doing, this research also implicitly attempts to contest the extent of theory which conceptualizes journalism as an “interpretive community” (B. Zelizer, 2004, p. 8). Understanding Journalism Journalists are situated within communities that co-create a shared communicative narrative about what journalism is within a specific society (Berkowitz, 2000). However, that 3 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 4 shared communicative narrative does not always provide an obvious consensus as to what it is that makes a journalist. The job description of a journalist is to report the news, however how one engages in that basic practice depends largely upon one’s shared local culture. For example, French television news emphasises visual appeal and personal style whereas German television news focuses on serious, distanced reporting (Grieves, 2011). In the first instance, journalists must gather and report their news with emotionality and in the later case, German reporters must perform their journalistic role with clear on their objectivity. These international differences in the practice of journalism highlight how journalism is fundamentally an expansively adaptive and culturally responsive institution (Deuze, 2005). Yet, differences in practice across geographic regions (Donsbach & Klett, 1993; McNair, 2003) are still largely appropriated to a generalized understanding of journalism – or to a geographically combined west/east divide that fails to accurately address most of the planet (Curran & Park, 2000). There is a persistent endowment of journalism as a near universal ideology that maintains an “inability to consider journalism in the context of other fields of cultural production” (Conboy, 2009, p. 307). Part of the hesitance to engage with rather complicated research exploring the complexities of local culture in journalism has been this assertion that there are a “universal stock of professional beliefs” (Donsbach & Klett, 1993, p. 79) that work to shape journalism. This appropriation has been expanded somewhat to generalized typographies of journalism around the world (D. Hallin & Mancini, 2004). However, in reviewing their extremely influential work, Hallin and Mancini (2012), suggest that their truncated comparative analysis still does not successfully describe all the variations – and similarities – in journalism systems. Thus, much research adheres to a shared media theory in the face of such complexity and continues to seek out a ‘fundamental’ nature of journalism. As Deuze (2005) has said, professional values and beliefs may “shift subtly over time; yet always serve to maintain the dominant sense of what is (and what should be) journalism” (p. 444). This universal stock of beliefs has been called the professional ideology of journalism (B. Zelizer, 2004), which translates to an ecumenical set of 4 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 5 everyday expectations and normative behaviours that define what it means to be a journalist (Donsbach, 2008). Yet, this focus has led to a continued shift away from “the basic yet overlooked fact that journalists use news to achieve pragmatic aims of community” (B. Zelizer, 1993, p. 82). With the development of public journalism throughout the 1990s, researchers have suggested that global journalism, as a social institution, increasingly empowers audiences as engaged and active citizens of the world (Rosen, 2000). Thus, a journalist’s own self perceptions of their societal role are integrated within a larger set of universal journalism traits, which include public service, but also objectivity, autonomy, immediacy and ethics (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001). These traits might be applied with different levels of emphasis around the globe, but they are said to be integrated into an international ideology of journalism and journalistic practice (Brennen, 2000). This practice maintains institutional core values, such as relevance, truth, public loyalty, autonomy, engagement (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2007). Some have argued that professional autonomy (Singer, 2007) remains at the axiomatic source of that collective practice. Research that maintains geographical, but notably not cultural, distinctions in how journalists think of their own societal function, suggests that variances may be the result of tension between autonomy and heteronomy (Bourdieu, 2005) and the inter-relationship between a journalist’s own perceptions in regards to appropriate levels of interventionism, power distance, and market orientation (Hanitzsch, 2011). These perceptions can be viewed as points of ideological comparison for journalists around the world (Deuze, 2005). Embedded within these perceptions is how a journalist negotiates their own culture and audience. Servicing that audience is a quality that has been found to be central to a journalist’s satisfaction with their job (Weaver, 1998). This link between audience service with job satisfaction makes intuitive sense if indeed public interest, and a meaningful cultural connection to that public, is intertwined with how a journalist perceives their own societal role. However, there is very little research that examines both audiences and journalists and asks what the institution of journalism should, or does, look 5 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 6 like within a society (Heider, McCombs, & Pointdexter, 2005; Tsfati et al., 2006). What studies do exist are generally grounded in public opinion survey comparisons of audience and journalist perceptions of bias in the news (Durante & Knight, 2009; Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2006). Further, the overwhelming weight of research conclusions have been drawn largely from western societies, which have a level of ideological consistency embedded within their largely democratic systems of governance (Hanitzsch & Mellado, 2011). One notable exception to the appropriation of a global journalism ideology, was an expansive study examining 1,800 journalists in 18 countries (Hanitzsch, 2011) that found a ‘detached watchdog’ milieu predominated throughout western journalism whereas an ‘opportunist facilitator’ milieu was found to be prevalent in developing countries. The cultural expectations and societal forces within local geographical regions informed these milieus. However, the findings were appropriated across broad conceptual categorizations of east and west and did not fully address the interplay between local cultures and journalism practice. It should be noted that the possible milieus described are also similar to the well known conceptions of western journalist roles put forth by Weaver and Wilhoit (1996): interpretive/investigative, disseminator, adversarial and populist mobilizer. Whereas western journalists have generally viewed their own professional roles as a combination of both the disseminator and interpretive/investigative (Weaver & Wilhoit, 1996), the importance of the dissemination of information has decreased over time in America in particular (Weaver, Beam, Brownlee, Voakes, & Wilhoit, 2006). Examinations of how audiences in ‘western’ societies feel about journalism have found support for four professional dimensions: good neighbour, watchdog, unbiased and accurate, and fast (Heider et al., 2005). One study looked at how bloggers (an audience of sorts) spoke about journalism and found they valued truth, authority, freshness, transparency and community thinking (S. Robinson & DeShano, 2011). Still other research has found that active audiences often believe that journalism is embedded with bias (Eveland & Shah, 2003) and is not worthy of 6 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 7 public trust (Kohut, 2004). This lack of trust may be traced to public sentiments, which value accuracy and unbiased reporting far more than speed or serving as a watchdog – two characteristics that are widely supported by journalists who see these as essential defining aspects of their profession (Beam, Weaver, & Brownlee, 2009). Thus, American journalists conceive of the news as a critical fourth estate, keeping watch over government corruption and business largesse, while survey data from western audiences demonstrates more support for journalism providing a community forum and offering interpretive solutions to problems (Heider et al., 2005). These values of western journalists and those suggested to be prevalent in developing countries have been surmised from detailed census data of journalism traits and reported professional values, but have largely not been connected back to the cultural forces that shaped them. Normative behaviours in journalism are largely seen in academic research to be the result of the values embedded in journalism practice and training. Such an approach to understanding journalism misses much of the nuance in journalistic practice and reception that derives from a shared understanding of local culture, which then shapes journalism as a cultural institution. Culture and the Hierarchy of Influences Model The seminal Hierarchy of Influences model, first put forth by Shoemaker and Reese (1996), is extremely valuable in its recognition that journalism is affected by a complex nexus of influences. The model can be demonstrated visually through a series of concentric circles that describe the growing relative influences of individuals, routines, organizations, extramedia factors, and ideology (Shoemaker & Reese, 1996). Notably missing from this list is culture, which could feasibly be encapsulated somewhat peripherally into the overarching ideological level of influence – although at a definitional level this is problematic given that several ideologies can exist within any particular culture. Further problematizing the integration of culture and ideology in the Hierarchy of Influences model is the assumed ‘top-down’ transmission, which is rooted in Marxist critical/cultural theories of capitalism and hegemony 7 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 8 (Herman & Chomsky, 1988). This approach views ideology as deriving from “higher power centres in society” (Shoemaker & Reese, 1990, p. 223) and, as such, misses much of the contextual cultural influences from the communally oriented ‘bottom-up.’ If, on the one hand, “it is impossible to separate news from community” (Deuze, 2008, p. 850), then local community and culture needs to be further integrated into understanding journalism as a socially embedded institution of meaning with an enveloping level of influence on journalism praxis. It has been noted that the list of influences on journalism is potentially endless (De Beer, 2004). As other research has already argued (i.e. Hanitzsch et al., 2010), this sense of endlessness may be the reason why so much academic scrutiny has centered on a hierarchy of influences that can be clearly defined: for example, political influences (D. Hallin & Mancini, 2004), economic forces (Bagdikian, 2000), and the organizational structure of journalistic institutions (Altmeppen, 2008). However, this emphasis misses the encompassing cultural forces that work to concomitantly shape the political, economic and organizational environment of the journalist and their audience. Culture, as manifested through learned behaviour patterns, is evidenced in specific language, traditions, and beliefs and it informs all social institutions, including journalism. Yet, for example, when public journalism initiatives in Denmark and the United States were recently compared and some striking differences were found in the implementation and practice of public journalism in these countries (Haas, 2003), culture was not explored as a contributing influence. Differences were attributed to journalist beliefs that were formed through shared journalism training, the development of populism within the Danish press system, and the organizational structure of news in Denmark. While the study had many intriguing and thought-provoking theoretical conclusions, all of the causal influences could be clearly connected to specific levels within the Hierarchy of Influences model and explained without any mention of culture. Couldn’t the continually evolving and repeated human interactions unique to Danish culture have helped to create a different journalistic system there? How do the learned behaviour patterns and 8 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 9 perceptions of Americans inform journalism in that country? These avenues of inquiry have been repeatedly overlooked in academic research and problematize contemporary journalism theory. In an article titled, “Understanding the Global Journalist: A Hierarchy-of-Influences Approach,” Reese (2001) returns to his theory to explore the comparative influences on journalists around the world. However, he does so in specific relation to the five-tiered influences first put forth and thus largely misses the profound influence of culture. In the article, which is explicitly aimed at examining differences in journalism around the world, the word culture is only mentioned twice. Comparative differences that are found amongst global journalists are attributed to differences in the hierarchy of influences without addressing the interrelationship of culture in the creation, constitutive existence, and propagation of those influences. The extramedia level of influence includes audiences that exert ‘market-driven’ pressure on journalists (Keith, 2010). Differences in audience influence are largely measured as differences in capitalistic systems and not differences in culture. Albeit rare, there have been a few examples of research comparing audience and journalist perspectives on what journalism means within a particular cultural context. Two recent examples were set in Israel and Finland. The first employed empirical survey data to compare what journalists and the public perceived to be the “core tenets of the journalistic profession” (Tsfati et al., 2006, pp. 153-154). That research found that while journalists were united in their understanding of journalism norms as an embodiment of knowledgeable interpretation, an important disconnect in perceptions between them and the public, which valued objectivity and neutrality, led to a lack of trust in journalism within the Israeli public sphere. Research based in Finland found audiences interested in what has been labelled marketable journalism. Audiences believed that journalism should be “combination of news and surprise, should make use of emotions and story-telling, give the reader guidance, and, particularly in relation to female readers, focus on celebrities who are believed to interest people” (Hujanen, 2008, p. 190). In the Israeli study of audiences and journalists, Tsfati (2006) does note that local attitudes toward freedom of speech in Israel are coloured by individual 9 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 10 positions on the Israeli-Arab conflict and similarly, Hujanen (2008) comments on the local media environment in Finland. Yet, while both studies acknowledge a cultural context to audience perceptions, they do not integrate that unique circumstance into their conclusions. These omissions in journalism theory need to be examined further given that journalism holds a central position within a larger circuit of culture that informs everything from economic activities (V. Zelizer, 2011) to social relationships to interpersonal associations (Oyserman & Lee, 2008) to patterns of production and consumption (Grinblatt & Keloharju, 2001). Local cultures constructively create independent bodies of shared knowledge that are regarded collectively as providing important symbolic capital. This cultural essentialism forms the fundamental structure of normative behaviours within social institutions and thus must be considered as a multi-directional influence within and between each of the five hierarchies of influence. If research is to have a better understanding of journalism, it must also understand the cultural context of its audiences and its journalists. This research aims to explore the ideology of Samoan journalism, from the perspectives of both audiences and journalists, with a specific focus on the role that local culture plays in those viewpoints. Samoa was chosen as a case study given its rich cultural traditions and its relative nascence as a democratic country, still very much constructing what journalism is within its borders. Examining Samoa is also important given that so little research has been done in the Pacific Islands. If research does not stretch beyond largely European and North American boundaries, “significant aspects of a national field may become naturalized and thus remain invisible to the domestic-bound researcher” (Benson, 2005, p. 87). Journalism and Samoa In 1899, the Tripartite Treaty was signed whereby America took control of what became known as American Samoa, Britain withdrew from the area, and Germany placed colonial rule over what is now Samoa. At the time, Samoa was titled Western Samoa as a discursive binary to American Samoa. New Zealand replaced Germany as the colonial ruler of Samoa in 1914 when 10 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 11 World War I began and maintained that control until Samoa was officially granted political independence in 1962. Thirty-five years later, in 1997, Western Samoa officially became The Independent State of Samoa and their freedom from occupation was formally recognized. By naming themselves simply Samoa, the country placed itself – discursively at least – as the central pivot point from which American Samoa was now seen as a satellite in opposition to Samoa. This has had a profound impact on the people of Samoa and has provided a strong linguistic connection for Samoans to their unique providence as the only ‘true’ Samoans. Journalism certainly existed in Samoa before their political independence in 1962, but those publications were under colonial rule and as such could largely not be seen as an accurate reflection of Samoan journalism. Newspapers, such as the Samoa Times (1877-1881, 1888-1896) and the Samoa Weekly Herald (1892-1900), were published by European settlers and struggled to maintain a profit amongst such a small expatriate community (Spennemann, 2003). The sporadic publications of various news outlets, such as the Samoa Guardian (1927-38), the Samoa Herald (1930-36), and The Samoa Bulletin (1950 – 67), continued throughout the twentieth century but none lasted very long due to the costs of publication in such a small market. In 1978, the Samoa Observer began publishing under the editorial reign of a local Samoan, Sano Malifa, and has been the overwhelmingly dominant newspaper in Samoa ever since. The near monopoly of the Samoa Observer group publishes three newspapers in Samoa: The Samoa Observer from Monday to Friday, the Weekend Observer on Saturday, and the Sunday Samoan. They have a weekly readership of 350,000, in a country of less than 200,000 people (Malifa, 2012). The Observer has succeeded in Samoa largely due to its dominance in the market. There are a handful of other commercial newspapers in Apia, such as Le Samoa News and the Samoa Times, but they are very small institutions with only a few employees. These outlets have very limited circulations. In addition, the government owns a small news publication, Savali, which presents “the government’s views on the issues, national events and news of public interest” (Pacific Media Centre, 2011). The government has no ownership stake in other media outlets. 11 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 12 All of the various media in Samoa have an online presence that is presumably targeted to Samoans overseas given the relatively sparse connection rates and Internet access in Samoa. With a population of just under 200,000 people, only 4.7%, or roughly 9,400 people, have Internet access in the country (Internet World Stats, 2011). Indicating the importance of the international market, the publishers of the Savali newspaper website stated that it was created specifically to create “a bridge between the Samoan people and (the) international community” (Pacific Media Centre, 2011). The Samoa Observer has an online web presence as well, in which the entire publication is uploaded in pdf form several days after the original publication date suggesting that the immediate temporality of local content is not of a high importance. Soon after the Samoa Observer began, the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) was voted into Parliament in 1982 and has remained in power, except for a brief period in 1986, since that time. The antagonism between these two fundamentally central Samoan institutions has been present from their inception. In response to this early conflict, Malifa and 14 other local journalists created the Journalists Association of Western Samoa (JAWS). Their founding constitution states that their objectives are to promote cooperation among journalists and an understanding of the role of journalism in Samoa; to undertake activities that will lead to improved training of members and increase professionalism; to establish and uphold a code of ethics and to develop and maintain freedom of information and expression (Journalists Association of Western Samoa, 2006). Although these were their stated objectives, journalists have been very slow to create any formalized codes of journalistic practice. In 2006, at the behest of JAWS, the British Thomson Foundation was drafted to finally develop those codes of journalistic practice and create a media council body. Seven years later, there still has been no agreement. Further, the initial focus on improving journalism training has not translated into more educated journalists. Journalists in the Pacific receive little education in comparison to the West (Robie, 2004). As a point of contrast, almost half of American journalists have received journalism training (Weaver et al., 2006), which can range anywhere from specific professional 12 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 13 courses in newswriting to Master’s degrees that theoretically analyze journalism as an institution of power. Samoa has a two-year, professionally focused journalism-training program at the National University of Samoa, which has been in existence for twelve years. However, it has seen very few students to completion. Journalism, as a social institution in Samoa, has remained in a period of contested negotiation throughout its conflicted recent past. In Samoa, journalists work under the threat of the 1992 Printers and Publishers Act, a law that “directs publishers and editors to reveal their sources of information to government leaders such as Prime Minister, cabinet ministers, MPs, and heads of government departments, who claim they have been defamed by the media, mainly newspapers” (Sano Malifa, 2010, p. 41). In 1994, the Samoa Observer’s editorial offices and printing press were incinerated in an arson attack that “many believed was retaliation for the paper’s reporting on allegations of government corruption” (Global Journalist, 2000). The fire occurred after corruption stories were published. Four years later, Samoa passed legislation that allowed public funds to be used for legal fees of government leaders in civil defamation lawsuits against the media (Global Journalist, 2000). Taken together, many journalists in Samoa live within what the Editor-in-Chief of the Observer has called a “culture of fear” (Malifa, 2011) whereby critical news coverage, can potentially spur litigation that can extend indefinitely through lengthy court cases that are fully supported by public funds. Those public funds are spent without much critique from Samoans who have generally not held journalists in high esteem (Pearson, 2000, p. 24). Indeed, audience members have responded to threats on journalistic freedom with a general indifference. Many continue to view journalism as a western import based on a legacy of early colonial administrators who generally reported only European news in early Samoan newspapers (Singh & Prasad, 2008). This indifference persists despite the craft of storytelling (fagogo) being highly prized in Samoan culture. Tusitalas (storytellers) are given uniquely honorable cultural status as venerated matais (village high chiefs). Talona (talk or discussion), 13 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 14 which emphasizes discussion of opposing views without any “predetermined expectations for agreement” (D. Robinson & Robinson, 2005, p. 15), is a repetitious, timeless process of deliberation found throughout the Pacific and practiced by experienced tusitalas. These storytellers rely on both the spoken and written word in a country with the highest rate of literacy in the South Pacific (99.7 percent), ranking ahead of New Zealand (Cass, 2004). Samoa is a conservative culture that is based upon fa’aaloalo (respect), which would presumably conflict with investigative journalism. However, cultural examinations of Samoa have also indicated that the country is also inherently assimilative – to such a degree that Samoans have “incorporated introduced beliefs and practices so completely that they are now considered indigenous” (MacPherson & MacPherson, 1990, p. 8). Samoans have a demonstrated propensity to interconnect historical traditions and contemporary norms into fa’a Samoa (Samoan culture). For example, the western-modelled Parliament is comprised almost exclusively of traditional matai. The 49-seat Parliament is divided as follows: 47 dedicated Samoan seats that can be held only by those who also have revered and respected matai status and 2 seats that are reserved for non-Samoans. In so doing, Samoans have integrated their own, highly valued, traditions and customs into ‘western’ models of democracy (Lawson, 1996; So'o, 2006). They have also integrated English language instruction into their educational system. Schools in Samoa generally instruct in Samoan until year three and from thereon, either English exclusively, or a mix between the two languages. Samoan remains the primary language used within the country, although both Samoan and English are the official languages. In Samoa, culture, as defined as the intersection of belief and practice (MacPherson & MacPherson, 1990), is demonstrably viewed in everyday life through ritualized meals, distinctive clothing, hierarchical titles, visible tataus (tattoos called pe’as for men and malus for women), and obvious role separations based on title, age and gender. Respect for elders is central to fa’a Samoa - elders eat first and are served by the younger aiga (family). Students simply do not 14 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 15 question their teachers; children do not question their parents; workers do not question their bosses; parishioners do not question their priests and citizens do not question their matai. These rich traditions are protected, in part, by Samoa’s isolation in the Pacific islands, which has reinforced the socio-political context of insularism (Taule'alo, Fong, & Setefano, 2004) and continues to inform the slow pace of social and democratic change (Jones, 1996). Social institutions, such as journalism, integrate these rich cultural traditions into daily practices. Yet, little is known about how Samoans, within their own cultural context, view journalism or how journalists themselves feel about their own profession. This research asks what is – and also what should be –journalism in Samoa. Further, audiences and journalists will be questioned as to their own perceptions of the role that Samoan culture has on journalism. Given the importance of journalism as “a site where a community’s sense of self is represented and negotiated” (Bogaerts, 2011, p. 400), this study posits these points of interrogation as guiding questions for analysis. Methodology Focus groups and interviews were conducted with 21 journalists (12 male, 9 female) and 47 audience members (28 male, 19 female) in Samoa. Most of the 68 total participants contributed through focus groups, although at times that was not possible and data were collected through individual interviews. Interviews were conducted individually with 18 journalists and 13 news audience members. Seven focus groups, ranging in size from 3 to 7 participants, were conducted with 34 news audience members. One additional focus group involved 3 journalists. Of the total 21 journalists involved in this study, 8 were directly affiliated with the Samoa Observer although almost all of the journalists had some previous connection with the dominant Samoan newspaper. Seven of the eight Observer participants were reporters and one was the Editor. The thirteen remaining journalists were freelance reporters or worked as reporters for the Samoa Times, Le Samoa, Savali, or Talamua Magazine. Audience members ranged in age from 19 to 63 years old. All of the audience members presently lived in Apia, but many were originally 15 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 16 from outside of the capital and grew up in small seaside villages. Audience participants varied in socioeconomic status, employment and familial responsibilities. None of the journalists at the Samoa Observer had training in journalism. Only 3 of the journalists interviewed for this study had some form of training, but that came at a much later stage of their career and, with the exception of one participant, was very brief. The overwhelming majority had no formal journalism training at all, although all had completed Year 13 study (the equivalent of high school). This primary research was conducted between June and August of 2011 and largely took place in coffee shops, public meeting areas and restaurants throughout Apia, the capital of Samoa. Journalists, and audience members were found through a ‘snowball’ methodology – mainly through word of mouth, but also via email and Facebook. In a small country, repeated requests to chat over a cup of coffee (the ‘compensation’ offered for those who had a few moments to ‘talk about journalism in Samoa and Samoan culture’) were warmly received. Audience members were included in this study if they read a Samoan newspaper at least three times a week. Journalists were included if they were presently employed as a journalist in Samoa or had worked as a journalist in Samoa at some point in their life. After each interview and focus group, participants were asked if they knew of anyone further that would be qualified and willing to participate in this research. Using theoretical saturation as a goal, focus group meetings were added until little new information was obtained (Krueger, 1988). Focus groups and interviews followed a loose structure that was often dictated by the direction of discussion. In several instances, follow up interviews were held for further clarification and discussion. In all meetings, it was ensured that each participant was asked two central questions, in varying order and degrees of emphasis: What is – and also what should be – journalism in Samoa? Is there a relationship between culture and journalism in Samoa? These questions were purposefully broad to allow participants to articulate their own perceptions. They became part of a larger set of general questions that evolved through discussion, but were 16 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 17 fundamentally central to every interview and focus group. In all cases, this researcher aimed to be as removed from discussions as possible, which “allows one to observe the local co-construction of meaning of concepts during an ongoing discussion by individuals but under the interactive influence of group” (de Cillia, Reisigl, & Wodak, 1999). Such an approach was particularly appropriate given the cultural context of the interviews that inherently depended upon shared symbols of meaning. The discourse from interviews and focus groups was understood as the representation of a unique province of knowledge, derived from an individualized and exclusive perspective (Hall, 1997). However, this assessment was also situated within a larger shared, cultural environment that necessitated a high level of social and institutional awareness. As such, respondents were asked several times, and in varying ways, about their own understanding of Samoan culture as well as journalism. The analysis of interview data followed other interview research examining large amounts of interview data (Kinefuchi, 2010) and discourse analysis exploring knowledge construction (Fairclough, 2003). This research used a phenomenological approach, which acknowledges that any reality constructed from a narrative exchange between individuals is inherently co-created through perceptions between the interviewer and the interviewee (MerleauPonty, 1962). Any results reported within this research are intrinsically tied to the researcher’s own perceptions as the initial recipient of these messages (Moran, 2000). The goal is to extract as much of the interviewees intended meaning as possible (Kvale, 1996). Toward that goal, this research relied on the steps detailed in previous research (Kinefuchi, 2010), which involved first transcribing all of the interview content and reading through those transcripts in their entirety without any notations. The transcripts were then re-read, with special attention to recurring words and phrases, in an open and self-selective process (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) that revealed associations between journalism and one’s sense of identity. These associations were identified as emerging discourses and viewed within a larger institutional and social context. The transcripts 17 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 18 were then read a third time to solidify themes, or dominant discourses (Fairclough, 1995), that existed across interviewees. In several instances a ‘member check’ (Creswell, 1998) was conducted and participants were asked again if the themes uncovered were reflective of their own feelings. Member checks are “the most crucial technique for establishing ‘credibility’” (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 314). Once confirmed, this interview data was then contrasted against literature on journalism and identity to better understand the interviewee responses. Given that journalism is in a state of constant evolution, and that the results reported here are from meetings that took place over three months, conclusions should be viewed as a representation of one particular moment in time. Results and Discussion Journalism as a site of cultural struggle Normative behaviours were found to be deeply embedded into an acute awareness of culture from both audiences and journalists, however positioned in strikingly different ways. Journalists drew on indigenous cultural values to support their work; in comparison, audiences saw journalism threatening or counter to those same values. Audiences’ Weberian perspective saw the rise of journalism come at the cost of cultural tradition. They viewed journalism as a colonial institution that existed largely outside of their Samoan culture and therefore held it largely in disdain. Audience members largely disregarded any suggestion that journalism could be integrated into fa’a Samoa. Due to this cultural disconnect, audience and journalist estimations of journalism in regards to interventionism, market orientation, power distance and the autonomy/heteronomy divide were philosophically inverted. Journalists said their level of market orientation and interventionism were inappropriate given their perceived role of importance as an informed tusitala (storyteller) in Samoan society. They said they needed to have more ability to intervene, perform their role as investigator and also rely less on market forces, so that they could properly tell the story of Samoa. Journalists said they had to validate their roles as tusitalas so that they could do investigative work - rather 18 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 19 than doing the investigative work as a means of validating their perceived tusitala status. One journalist said, “nobody can tell the story of Samoa but us. We are tusitalas.” Another said, “as tusitalas we need to dig deeper.” In order to ‘tell their stories,’ freedom from government oversight was needed. As one journalist said, “they (the government) are always watching us. What can we do? This is no way for Samoa.” Here, the journalist figuratively unites the perceived proper level of interventionism with the identity of the entire country. In doing so, he views the perceived governmental restraint as antagonistic to Samoan culture. Another reporter said, “they (early colonialists) might have reported rubbish, but even they didn’t have to deal with this. It’s not right.” By using the discursive phrase, “even they,” the journalist connects his own plight with those seen as anathema to fa’a Samoa – the colonialists that withheld Samoan culture from locals for decades. Here, even the noncultured, abusive colonialists escaped government scrutiny, which is an affront for those who view themselves as tusitalas, and as such, rightfully titled to conduct journalistic investigation. This challenge is moralistically framed within the culturally created parameters of right and wrong. The often stated phrase, “we are modern tusitalas” was invoked repeatedly by journalists in this study. In drawing upon this traditional title of tusitala, journalists were positioning themselves as worthy of cultural attention and honor. Journalists contrasted their tusitala status against government forces that were positioned discursively outside of culture. One journalist commented, “they (the government) is not us. They’ve been in it too long.” The journalist is referencing the government in general but the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) in specific. The party is rhetorically removed from what it means to be Samoan (to be “us”) because of their length of power in what is positioned as a colonial government system (to be “them”). One journalist said, “I don’t think they (the government) knows what a tala (Samoan money) looks like!” In this statement, the journalist simultaneously associates foreign influences to a government system that both operate outside of Samoan culture. In creating this argument, the journalist is then in opposition to these forces as a cultural defender of Samoa. 19 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 20 While autonomy was viewed as a central and necessary part of practicing journalism, it was celebrated as an end to colonial intervention – and not necessarily as a principled journalistic convention. Journalists saw themselves as tireless advocates for autonomy and freedom from government intervention as a cultural stance of Samoan pride. “I have been pushed, shoved, threatened…you, you just name it…all by people who supposedly are supposed to be leading Samoa. Disgraceful. These people have been doing this stuff since the Germans. It’s about honour.” Here, the distance from power (read as German colonialists against fa’a Samoan) is welcomed by journalists who view themselves as tusitalas supporting what it means to be Samoan. Any opposition to this is discursively dismissed moralistically as “disgraceful.” In contrast, audiences saw the level of intervention in journalism to be far too high and journalism itself operating at a level that was too autonomous within Samoan society, thereby removing the institution of journalism further away from Samoan culture. Audiences reported seeing journalists as behaving outside of normative Samoan cultural restrictions, whereas the government represented fa’a Samoa on a global scale. One audience participant said, “what is the world thinking of us? About Samoa? Journalists need to understand that when they report.” Audiences saw the act of journalism as having no respect for culture, whereas the government was trying to protect cultural value. This lack of respect had a clear monetary relevance as well. “If tourists read this stuff, why would they want to come here? They want to come here and learn fa’a Samoa. But not after seeing this…this… kinda thing.” Whereas some research has suggested “journalism must provide a forum for public criticism” (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001, p. 137), audience members saw this level of criticism as hurtful to their image as a tourist destination and counter to preserving Samoan culture. The value of these tourist dollars cannot be understated in a small Pacific island economy. As one audience member said, “they should be telling our stories. For us.” When asked to consider what journalism perhaps should be in Samoan society, the overwhelming majority said some variation of the response that journalism should “tell us what is 20 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 21 going on.” By this, it was meant that they wanted to know what church dances, concerts, and cultural events were happening in their village or the main center of Apia. A strong majority of audience members said that journalism should be some variation of a timetable of cultural events. This role is similar to previous research finding that journalism can serve as a disseminator of information (Weaver & Wilhoit, 1996). However, newsworthiness of potential topics was not judged by news values, such as unexpectedness, negativity, or proximity (Bell, 1991). Rather, it was the cultural relevance of that topic that suggested its news value. The events that audience members wanted to know more about were unique to Samoa and not generally found in other countries around the world. Participants valued these events as distinctly Samoan events and spoke of them with a deep reverence. “There is always something going on, but now I don’t hear about it until after the fact. When did that change? Why don’t I see it (in the newspaper)?” Another said, “journalists should tell me what’s happening, so that I can see siva (traditional Samoan dance) or something.” One respondent referred to the traditional fa’ataupati (slap dance traditionally performed by Samoan men) when he said, “I wanna know who is slapping.” Respondents largely said that journalism maintained its role as a cultural timekeeper in the past, but this had now changed to what was perceived as a more antagonistic, and inherently western, journalistic role that was devoid of its cultural specificity. An older woman spoke at length about the loss of shared cultural knowledge because stories about fa’aaloaloga (formal presentation of gifts) no longer predominated news content. These gifts continue to be shared at public events, such as weddings and funerals as well as church openings. However, she stated “we used to see the beautiful fa’aaloalogas. Now, we just see how horrible the Prime Minister is – or how bad some matai is. That isn’t even important to me. Why should I care?” Still another audience member said that he just wanted to know “if Manu is in town.” Manu Samoa is the national rugby union team. This review suggested that there are politics in representation (Cottle, 2000), but there are politics in nonrepresentation as well. Audiences saw the non-performance of journalism as a cultural timekeeper to have a 21 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 22 deleterious impact on Samoan culture and therefore positioned journalism in opposition to fa’a Samoa. Cultural knowledge as journalism training When asked about their qualifications to be journalists, audience members generally eschewed what they viewed as minimal professional knowledge but equated that knowledge to cultural authority. They cited a lack of training in journalists as a problem in contemporary Samoan journalism but then spoke at length as to the cultural failings demonstrated through weak reporting. This parallels earlier research finding that the quality of imported western journalism training programs was seen as lacking with little input from locals and a lack of attention to regional culture (Wickham, 1996). However, audiences in this study equated necessary journalism training with cultural knowledge; what audiences viewed as a poor display of cultural authority or understanding was manifestly termed as a lack of journalism training, but equated to a lack of cultural knowledge. For example, one particular focus group exchange among audience members: Respondent A: “Where do these people come from anyway? Where have they been trained?” Respondent B: “I don’t think they have no training.” Respondent A: “I know. It’s not Samoan. You don’t act like that. It’s not right” The logistical connection here is between a lack of demonstrable Samoan cultural norms to what is described as poor journalism skills. Another audience member said, “they (journalists) need to be taught a bit more, sometimes. A bit more about what to say. How to say it – in Samoa. Here.” The lack of education is again not in journalism training but in fundamental Samoan ways, which will then improve the quality of journalism in Samoa. This research suggests that the lack of regard for journalism in Samoa found in previous research could be due to perceived behaviors operating outside of accepted cultural normative limits and not to shortcomings in journalism training. In contrast, when asked what their qualifications were to be a journalist, almost all of the journalists interviewed maintained that their qualifications resided in their Samoan nationality. 22 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 23 One respondent said plainly, “You can’t be a journalist in Samoa and not be Samoan. You just can’t.” This near universality in response signals a widespread connection with a shared culture that represents a unifying force in their journalism work. While a lack of formal journalism training was generally seen to be negative for journalists by audiences (although conceptually equated to a lack of cultural education), that training was also not uniformly viewed as necessary by journalists. Apulu Lance Polu, the founder and editor of Talamua media and past president of JAWS, has openly bemoaned the lack of journalism training in Samoa (Enoka, 2011). However, he also notes the centrality of Samoan ethnicity as a fundamental requirement for journalism in that country – even in lieu of journalism training. The need is for “Samoans to work in the local media industry” ("Interview with Apulu Lance Polu," 2001). In one interview, an editor stated, “I just interview people and see if they are willing to ask tough questions and dig up stories. Do they know Samoa? Do they know the right questions?” In his response, the editor directly equates the ability to ask questions with the cultural specificity of Samoan ethnicity. Journalists spoke of their understanding of cultural sensitivities and the implications that their reporting might have on their small, collectivist island, even though these considerations on the part of journalists were not widely recognized by audiences. Journalists understood that simply asking direct questions can be perceived as disrespectful in Samoan society (Pyne, 2011), although some research has argued that “such cultural protocols (do) not seem as inhibiting” (Pearson, 2000, p. 24) in contemporary Samoan journalism. That being said, “the words ‘constructive’ and ‘positive’ are routinely a prerequisite for any criticism of government” (Davis, 2012). In a statement that summarizes that tension, one journalist in this study said, “you definitely got to know how to pose the question so that people don’t get upset. But, you still got to ask the question. You have to know how to ask it though.” Such a perspective suggests implicitly the paramount importance of cultural authority in journalism. This cultural authority was actively performed as a loyalty to Samoan ethnicity. Journalists viewed their continued employment as a honourable dedication to Samoa’s future. A 23 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 24 reporter for the Samoa Observer said, “I know I could leave. But who can tell these stories? Who knows these stories? And how to tell them?” The reporter figuratively envisions Samoa as “an imagined community” (de Cillia et al., 1999, p. 149) that requires her own, Samoan, interpretive abilities to strengthen local culture and understanding. She saw her rationale to remain in Samoa as dedication to her love of fa’a Samoa. The reporters interviewed for this research reported a strong loyalty to their country and viewed journalism as their personal contribution to a progressive Samoan future. When one reporter was asked why they stayed in Samoa, he said: “This is my country. This is my people.” Journalists professed a sense of responsibility to their local culture in their decision to stay in the country. “There is no other Samoa. Only this one.” Another journalist echoed that sentiment when saying, “we are Samoan, not something Samoan.” This was a reference to American Samoa and situated the participant as part of a clearly defined, and proud ethnicity. The fundamental positioning of Samoan culture at the centre of journalism values, from both audience members and journalists, was repeatedly illustrated through a well-known and often-repeated narrative in the country. That narrative involved the perceived incorrect tsunami recovery reporting from New Zealander John Campbell in 2009 due to a presumed lack of cultural awareness. The initial reporting, which alleged that aid money was being misspent, received substantial attention in the Samoan press and a substantial amount of both journalists and audience members in this study referred to his reporting. In his televised report, Campbell pointed directly to a home behind him that was reported to have been reconstructed and then stated incredulously that it didn’t even have walls, but was supposedly fixed (Jackson, 2012). However, no fales (traditional Samoan homes) have walls; they are open, thatched structures whereby mats are rolled out at night for sleeping. The Prime Minister appealed to the Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) of New Zealand, but they ruled in favor of Campbell Live. This often cited example of poor journalism in Samoa was roundly attributed to poor cultural awareness. 24 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 25 Endurance as a cultural measure of journalistic value Both audiences and journalists spoke of journalism as a continuum of shared information. Audience members did not think that immediacy was important to journalism nor did journalists. Whereas audience members eschewed its presence as a fundamental flaw to what they saw as the failings of contemporary journalism, journalists stated that the value of their profession was largely its historical significance - serving as a permanent record for Samoa and as a prolonged antagonist to government largesse. The need for immediacy found in many audiences in developed countries simply was not present in the audience members that were interviewed for this study. One audience member said quite plainly, “what you (from outside Samoa) do is rush, rush, rush. Why? Why is it important? Where are you going? We (from inside Samoa) will get there when it is important to be there.” This slow pace of change is intrinsic to Samoan culture, which measures cultural movement in generations, not decades. As one audience member said, “if it is important, we’ll know about it. Maybe not today, but someday.” This perception of timelessness is culturally significant to Samoans who see their traditional history tracing far past the dates officially recognized as sovereign. A journalist respondent said, “we are not new. Samoa may be only 50 years old but fa’a Samoa has always been here. On this land.” Other reporters spoke of becoming free of colonial rule as if it was a recent occurrence and not an event with 50 years of history. “Don’t forget. Colonialists have only just left. We have to draw on the past to understand where we are going as, as a profession.” This past that is worth acknowledging, worth recognizing, is the past preceding colonial rule – when fa’a Samoa traditions first began without the influence of colonial inhabitants. The value of journalism is generally more in the “here-and-now than the there-and-then” (B. Zelizer, 2008, p. 80) and this emphasis on expedience is interwoven into journalism’s normative framework in many cultural contexts. However, as Zelizer (2008) rightfully asserts, the “treatment of the present often includes a treatment of the past” (p. 80). Journalists in Samoa 25 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 26 could not address what they do in the present without interjecting their shared culture, created through a long history of traditions. One journalist said, “there is no journalism without fa’a Samoa. There is no nothing without that. Fa’a Samoa is who…is who.. we are. Journalism is just a small part of that. I’m not a journalist first. I’m a Samoan first.” This primacy of Samoanness places her, as a journalist, on a continuum of cultural significance, and not in the tradition of journalistic pursuits. Conclusion The lack of journalism training for journalists in this study removes the possibility that any agreements found in regards to their perspectives on the journalistic profession were due to a common educational background in journalism. It could obviously be that these norms were learned ‘on the job,’ but journalists were drawn from a wide range of ages and a variety of unique professional experiences, suggesting that shared perspectives learned in a particular setting of employment was less likely. Further, there was a similarity in audience responses, which could not be linked through shared professional or familial experiences given their diverse backgrounds. This suggests that these commonalities, at least in part, could be attributed to a shared culture, which helped to direct the norms of Samoan journalists and perceptions of Samoan audiences. One analysis of these interviews could be rooted in how Samoan journalists and audiences negotiated the demands of their culture in opposition to the demands of their profession. At the heart of such an analysis would be the juxtaposition between modernity and tradition, between the future and the past. However, such an approach would inevitably place a negative connotation on either polarizing extreme – either explicitly or implicitly resulting in a recusant assessment of tradition, which has been largely categorized as antiquated, and a positive endorsement of modernity, generally seen as forward-thinking and innovative (Lawson, 1996). Such categorizations do little to assist a deeper understanding of how these two forces coalesce, and also contradict, one another in the formation of an entirely unique institution that would have 26 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 27 otherwise not existed. Other researchers (i.e. Bendix, 1967; Besnier, 2009; Giddens, 1991) have argued that modernity and tradition can work in dynamic concert to create societal institutions that are as unpredictable as they are distinctive. This research supports such an assertion and further suggests that such a multi-dimensional development and mutually informing evolution may potentially be that much more complex in societies where the weight of reliance on both forces is somewhat equalized, as is the case in the Pacific Islands. The reverence of tradition in the Pacific Islands has already been integrated into what could be categorized as ‘modern’ societal institutions, such as Parliament. This research would suggest that journalism needs to attempt a more public interconnection of fa’a Samoa throughout its colonial and capitalistic framework, whether seen as fully successful by audiences or not. Samoan culture was found to be centrally important to the perception of journalism from both journalists and audiences – for journalists, fa’a Samoa dictated what form of journalistic training was deemed necessary, the fundamental value of journalism to society, and the importance of a journalist’s work to Samoa; for audiences, fa’a Samoa created the framework for assessing journalism’s relative stature in Samoan society and the importance of journalism over time. This fluidity of fa’a Samoa into the norms and values of what is generally viewed as a ‘western’ institution of journalism, contradicts accepted modernistic markers of progress that are largely dismissive of culture and also challenges the conceptualisation of journalism as evolving from strict occupationally defined norms and routines. This finding suggests that further research should include culture in the creation and perception of journalism norms, values and routines. The concept of liquid modernity (Bauman, 2000), which suggests that culture can evolve and integrate tradition as it progresses, is applicable here as theory moves into a more contextual understanding of how journalism thinks of itself and how audiences interact with journalism. The examination of both audience members and journalists in this research helped to uncover the shared continuum of cultural symbols and traditional histories in the ideation of journalism, but it also became instructive in revealing the conceptual gap between both parties. In 27 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 28 this instance, and in this particular context, culture was constitutive to understanding and creating journalism. It was a fundamental requirement for making sense of journalism and for making meaning within the institution of journalism. However, audiences and journalists drew upon their culture toward largely opposing ends. Audience members did not recognize any display of journalism as a culturally integrated social institution, which may help to explain the poor perception of journalists in Samoa. These low estimations of journalism did not appear to be due to evaluations of journalistic performance, but to the lack of interconnectivity that journalism had with fa’a Samoa. If journalists wish to improve their standing within Samoan society, it may be that demonstrated performances of Samoan culture would help to bridge a stronger understanding and acceptance of journalism within the country. For example, talanoa (talk or discussion) could be further interwoven throughout journalism content. Such an emphasis in reporting could help to counteract some of the unwelcomed immediacy reported by audience members in contemporary journalism. In conclusion, this research suggests that an examination of journalism influences should include culture if it is to fully embrace the complexity of what journalism actually means within a particular society. If journalism is indeed a shared narrative, created concomitantly between audiences and journalists, then culture must be considered as enveloping and constitutive to the meaning of journalism. Culture is not the same as ideology and future work exploring the hierarchies of influence must consider the centrality of culture as the enveloping influence, rather than the generally accepted encompassing level of ideology. One culture has multiple ideologies, while culture is shared across disparate groups united in a common set of attitudes, beliefs and values. This research is only the beginning of a larger discussion as to the role of culture within the hierarchy of influence model. Research needs to continue developing this stream of inquiry through comparative studies that examine contrasting cultures and their own unique conceptualizations of journalism in specific relation to the hierarchy of influences model. 28 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 29 A limitation of this work is that all interviews and focus groups were conducted in English as the author does not speak Samoan. All of the participants spoke English, but at varying degrees of proficiency, so there was an inherent imbalance in comprehension. The researcher aimed to reduce the potentially biased cultural deconstruction of information through several member checks that confirmed the intended meaning of participants, but this remains a limitation of this research. A researcher who spoke Samoan could likely uncover more latent meanings that may have been missed in this analysis. The mono-cultural approach of this research limits any conclusions to Samoa alone, so much more expansive research is needed that examines the Hierarchy of Influences model in various cultures around the world. A further limitation of this work was the relatively small sample size. Future comparative studies should consider the benefits of a larger sample that may be accessed through survey questionnaires. 29 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 30 References Altmeppen, K.-D. (2008). The structure of news production: The organizational approach to journalism research. In M. Loffelholz & D. Weaver (Eds.), Global journalism research: Theories, methods, findings, future (Vol. 52-64). New York: Blackwell. Bagdikian, B. (2000). The media monopoly (6th ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Cambridge and Oxford: Polity Press & Blackwell. Beam, R. A., Weaver, D., & Brownlee, B. J. (2009). Changes in professionalism of U.S. journalists in the turbulent twenty-first century. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 277298. doi: 10.1177/107769900908600202 Bell, A. (1991). The language of news media. Oxford: Blackwell. Bendix, R. (1967). Tradition and modernity reconsidered. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 9(3), 292-346. Benson, R. (2005). Mapping field variation: Journalism in France and the United States. In R. Benson & E. Neveu (Eds.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field (pp. 85-112). Cambridge: Polity Press. Berkowitz, D. (2000). Doing double duty: Paradigm repair and the Princess Diana What-A-Story. Journalism, 1(2), 125-143. doi: 10.1177/146488490000100203 Besnier, N. (2009). Modernity, cosmopolitanism, and the emergence of middle classes in Tonga. The Contemporary Pacific, 21(2), 215-262. Bogaerts, J. (2011). On the performativity of journalistic identity. Journalism Practice, 5(4), 399-413. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2010.540131 Bourdieu, P. (2005). The political field, the social science file, and the journalistic field. In R. Benson & E. Neveu (Eds.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field (Vol. 29-47). Cambridge: Polity Press. Brennen, B. (2000). What the hacks say: The ideological prism of US journalism texts. Journalism, 1(1), 106-113. doi: 10.1177/146488490000100112 Cass, P. (2004). Media ownership in the Pacific: Inherited colonial commercial model but remarkably diverse. Pacific Journalism Review, 10(2), 82-106. Conboy, M. (2009). A parachute of popularity for a commodity in freefall? Journalism, 10(3), 306-308. doi: 10.1177/1464884909102572 Cottle, S. (2000). Rethinking news access. Journalism Studies, 1(3), 427-448. doi: 10.1080/14616700050081768 Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Curran, J., & Park, M. J. (Eds.). (2000). Dewesternizing media studies. New York: Routledge. Davis, G. (2012). Pacific media 'at peace' after bitter infighting over Fiji. Retrieved from Pacific Media Centre website: http://www.pmc.aut.ac.nz/articles/pacific-media-peace-after-bitter- infighting-over-fiji De Beer, A. S. (2004). Ecquid Novi: The search for a definition. Ecquid Novi, 25(fall), 186-209. de Cillia, R., Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (1999). The discursive construction of national identities. Discourse & Society, 10(2), 149-173. doi: 10.1177/0957926599010002002 Deuze, M. (2005). What is journalism: Professional identity and ideology of journalism reconsidered. Journalism, 6(4), 442-464. doi: 10.1177/1464884905056815 Deuze, M. (2008). The changing context of news work: Liquid journalism and monitorial citizenship. International Journal of Communication, 2, 848-864. Donsbach, W. (2008). Journalists' role perception. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication (Vol. 6, pp. 2605-2610). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Donsbach, W., & Klett, B. (1993). Subjective objectivity: How journalists in four countries define a key term of their profession. Gazette, 51(1), 53-83. Durante, R., & Knight, B. G. (2009). Partisan control, media bias, and viewer responses: Evidence from Berlusconi's Italy. NBER Working Paper Series, w14762. Enoka, T. K. (2011). Samoa: 'Dire need' for trained journalists, says Apulu. Pacific Media Centre. Retrieved from Pacific Media Centre website: http://www.pmc.aut.ac.nz/pacific-media- watch/2011-05-11/samoa-dire-need-trained-journalists-says-apulu Eveland, W. P., & Shah, D. (2003). The impact of individual and interpersonal factors on perceived news media bias. Political Psychology, 24(1), 101-117. Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. London: Arnold. Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge. Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2006). Media bias and reputation. Journal of Political Economy, 114(2), 280-316. doi: 10.1086/499414 30 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 31 Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Standford: Standford University Press. Global Journalist. (2000). Savea Sano Malifa, Samoa. Retrieved from http://www.globaljournalist.org/stories/2000/07/01/savea-sano-malifa-samoa/ Grieves, K. (2011). Transnational journalism education: Promises and challenges. Journalism Studies, 12(2), 239-254. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2010.490654 Grinblatt, M., & Keloharju, M. (2001). How distance, language, and culture influence stockholdings and trades. The Journal of Finance, 56(3), 1053-1073. Haas, T. (2003). Importing journalistic ideals and practices? The case of public journalism in Denmark. Press/Politics, 8(2, Spring), 90-103. Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (Vol. 2, pp. 1-74). London and Thousand Oaks: Sage. Hallin, D., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (Eds.). (2012). Comparing media systems beyond the western world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hanitzsch, T. (2011). Populist disseminators, detached watchdogs, critical change agents and opportunist facilitators: Professional milieus, the journalistic field and autonomy in 19 countries. International Communication Gazette, 73(6), 477-494. doi: 10.1177/1748048511412279 Hanitzsch, T., Anikina, M., Berganza, R., Cangoz, I., Coman, M., Hamada, B., . . . Yuen, K. W. (2010). Modeling perceived influences on journalism: Evidence from a cross-national survey of journalists. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 87(5), 5-22. doi: 10.1177/107769901008700101 Hanitzsch, T., & Mellado, C. (2011). What shapes the news around the world? How journalists in eighteen countries perceive influences on their work. International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(3), 404-426. doi: 10.1177/1940161211407334 Heider, D., McCombs, M., & Pointdexter, P. M. (2005). What the public expects of local news: Views on public and traditional journalism. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(4), 952967. doi: 10.1177/107769900508200412 Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. New York: Pantheon Books. Hujanen, J. (2008). RISC Monitor audience rating and its implications for journalistic practice. Journalism, 9(2), 182-199. doi: 10.1177/1464884907086874 Interview with Apulu Lance Polu. (2001). Retrieved from http://76.12.2.128/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3654%3Anew-tvand-radio&Itemid=59 Jackson, C. (2012). Tsunami aid feud: Tuilaepa lodges complaint. Retrieved from http://www.islandsbusiness.com/islands_business/index_dynamic/containerNameToRepl ace=MiddleMiddle/focusModuleID=19474/overideSkinName=issueArticle-full.tpl Jones, P. (1996). Changing faces of the islands. Australian Planner, 33(3), 1-10. Journalists Association of Western Samoa. (2006). History. Retrieved from Information on JAWS website: http://jawsexecutive.blogspot.co.nz/2006/01/history.html Keith, S. (2010). Shifting circles: Re-conceptualizing Shoemaker and Reese's theory of a hierarchy of influences on media content for a new-media era. Paper presented at the Texas Tech Convergent Media Resource Center and the Communication Technology Division of AEJMC, Texas Tech University. Kinefuchi, E. (2010). Finding home in migration: Montagnard refugees and post-migration identity. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(3), 228-248. Kohut, A. (2004, 11 July 2004). Media myopia: More news is not necessarily good news, New York Times. Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. New York: Three Rivers Press. Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the people should expect. New York: Three Rivers Press. Krueger, R. (1988). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Newbury Park: Sage. Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 31 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 32 Lawson, S. (1996). Tradition versus democracy in the South Pacific: Fiji, Tonga and Western Samoa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage. MacPherson, C., & MacPherson, L. a. (1990). Samoan medical belief and practice. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press. Malifa, S. S. (2011, 7 July 2011). Journalists must be allowed to protect 'sources', Opinion, The Samoa Observer. Retrieved from https://http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=259179750766232 Malifa, S. S. (2012). About Us. Retrieved 21 March, 2012, from http://www.samoaobserver.ws/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout= blog&id=46&Itemid=77 McNair, B. (2003). Sociology of Journalism. London: Routledge. Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. London: Routledge. Moran, D. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. London: Routledge. Oyserman, D., & Lee, S. W. S. (2008). Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, 311-342. Pacific Media Centre. (2011). Samoa: Savali newspaper launches new website. Retrieved from http://www.pmc.aut.ac.nz/pacific-media-watch/2011-02-16/samoa-savali-newspaperlaunches-new-website Pearson, M. (2000). Reflective practice in action: Preparing Samoan journalists to cover court cases. Asia Pacific Media Educator(8, January-June), 22-33. Pyne, L. (2011). Media in Samoa: Journalists' realities, regional initiatives, and visions for the future. School for International Training. Wesleyan University. Reese, S. D. (1990). The news paradigm and the ideology of objectivity: A socialist at the Wall Street Journal. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 7, 390-409. doi: 10.1080/15295039009360187 Reese, S. D. (2001). Understanding the global journalist: A hierarchy-of-influences approach. Journalism Studies, 2(2), 173-187. Robie, D. (2004). Mekim Nius. Suva, Fiji: University of South Pacific Book Centre. Robinson, D., & Robinson, K. (2005). Pacific ways of talk - Hui and Talaona. Retrieved from http://scpi.org.nz/documents/Pacific_Ways_of_Talk.pdf Robinson, S., & DeShano, C. (2011). 'Anyone can know': Citizen journalism and the interpretive community of the mainstream press. Journalism, 12(8), 963-982. doi: 10.1177/1464884911415973 Rosen, J. (2000). Debate: Public journalism. Questions and answers about public journalism. Journalism Studies, 1(4), 679-694. doi: 10.1080/146167000441376 Sano Malifa, S. (2010). Samoa: The Observer and threats to media freedom. Pacific Journalism Review, 16(2), 37-46. Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (1990). Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content. New York: Longman Publishing Group. Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content (2nd ed.). New York: Longman Publishing Group. Singer, J. B. (2007). Contested autonomy: Professional and popular claims on journalistic norms. Journalism Studies, 8(1), 79-95. doi: 10.1080/14616700601056866 Singh, S., & Prasad, B. (2008). Media for language and education in the Pacific Islands. Paper presented at the Media and Development: Issues and Challenges in the Pacific Islands, Lautoka, Fiji. So'o, A. (2006). The establishment and operation of Samoa's political party system. Canberra: Pandanus Books. Spennemann, D. H. R. (2003). The heritage of nineteenth century Samoan newspapers: A bibliographical documentation. Albury, Australia: Charles Sturt University. Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). The basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage. Taule'alo, T. u. u. I., Fong, S. o. D., & Setefano, P. M. (2004). Samoan customary lands at the crossroads - some options for sustainable management. Retrieved from http://www.mnre.gov.ws/documents/forum/.../2. tuuu et al.pdf Tsfati, Y., Meyers, O., & Peri, Y. (2006). What is good journalism? Comparing Israeli public and journalists' perspectives. Journalism, 7(2), 152-173. doi: 10.1177/1464884906062603 Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New York: Free Press. 32 CULTURE AND SAMOAN JOURNALISM 33 Weaver, D. (Ed.). (1998). The global journalist: News people around the world. New Jersey: Hampton Press. Weaver, D., Beam, R. A., Brownlee, B. J., Voakes, P. S., & Wilhoit, G. (2006). The American journalist in the 21st century: U.S. news people at the dawn of a new millennium. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Weaver, D., & Wilhoit, G. (1996). The American journalist in the 1990s: U.S. news people at the end of an era. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Wickham, A. (1996). Hidden perspectives on communication & culture in the Pacific Islands. Communication for All. Retrieved from http://www.waccglobal.org/en/19973-indigenous- communications/929-Hidden-perspectives-on-Communication--Culture-in-the-PacificIslands-.html Zelizer, B. (1993). Has communication explained journalism? Journal of Communication, 43(4), 8088. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01307.x Zelizer, B. (2004). Taking journalism seriously: News and the academy. London, Thousand Oaks: Sage. Zelizer, B. (2008). Why memory's work on journalism does not reflect journalism's work on memory. Memory Studies, 1(1), 79-87. doi: 10.1177/1750698007083891 Zelizer, V. (2011). Economic lives: How culture shapes the economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 33