12627637_Locke-Formal Instruction and Apprenticeship Learning Among Nepali Elephant Handlers (SAAG).doc (86Kb)

advertisement

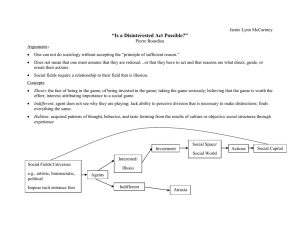

1 Piers Locke, University of Kent Formal Instruction and Apprenticeship Learning Among Nepali Elephant Handlers Preliminary fieldwork conducted in the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal in the summer of 2001 confirmed the significance of apprenticeship learning for the maintenance and utilisation of the elephant resources that are so crucial to the operations of the park. In the past, elephants in Nepal were used for big game hunting, transportation, logging and other agricultural work. But since the inception of Chitwan as Nepal’s first National Park in 1973, a new era of elephant deployment has been inaugurated, in which their main uses are in providing jungle safaris for tourists, assisting in the monitoring of large mammals like tiger and rhinoceros, as well as engaging in anti-poaching reconnaissance. The Research Context Data supplied to me by the Nepal Conservation Research and Training Centre (NCRTC) based near Sauraha, a village situated in the buffer zone that surrounds the park, and which acts as a nexus point for the local 2 tourist economy, suggested that Chitwan is currently home to 22 elephant stables or Hattisars, housing some 127 elephants or Hatti. This includes both park-operated Hattisars and also those of the 7 safari resorts licensed to operate within the park. The Park Management Unit itself was, at that time, employing some 132 elephant staff or Hattisares. Additionally, there is an elephant-breeding centre at Khoreshore, housing some 26 elephants, the aim of which is to enable the park to become selfsufficient in captive elephants and no longer reliant on India for the purchase of new animals. While the Park Management Unit and the NCRTC are mainly composed of high status immigrants from the hills (Pahari), the Hattisares are mainly drawn from the lower status, ethnic Tharu, considered the indigenous dwellers of the lowland strip of Nepal known as the Tarai (see Guneratne 2001 & 2002). Each stable is headed by a Subba, who acts as the main point of contact between officials and handlers. In each stable 3 staff are allocated to each elephant, ideally with their own specific responsibilities, and encoding a triadic hierarchy of authority. Of greatest seniority is the Phanit or driver, the handler with the most longstanding experience, who drives by pressing his toes on the temporal 3 region behind the elephant’s ears. Then there is the Patchuwa, whose job is to cut grass and to take the elephant for grazing and bathing. Lastly, there is the Mahout, whose job is to clean the stable and prepare the elephant’s supplementary diet, parcels of unhusked rice, molasses, and salt wrapped in grass, referred to in my presence as dana, meaning gift, or kuchi, as they are more commonly known throughout both India and Nepal. As observed at the Hattisar of the NCRTC however, these tasks appear to be interchangeable, with Phanits rarely seen doing any driving work, and with junior Mahouts regularly taking elephants out grazing. What matters is the seniority encoded by the hierarchy. The handlers of each Hattisar seem to enjoy a relative autonomy from park authorities in the everyday practices of elephant care (also attested to for West Bengal, and Kerala in an Indian handbook for Mahouts; Namboodiri (ed) 1997), coming in to close contact mainly through the issuing of specific tasks and the cooperation that they require. However, there is a recognition that Hattisare practices are less than optimally integrated with park agendas, in addition to which there are persistent personnel problems, with many handlers quitting through dissatisfaction, and others lacking in motivation and commitment. 4 In part, this probably reflects changes in the pattern of recruitment and assignment of Hattisares. Lynette Hart claims that the former cultural tradition of elephant driving being passed from father to son, and of drivers maintaining a partnership with a specific elephant for life, (still apparent in her co-authored study of Mahouts in South India [Hart & Sundar 2000]) is decreasing, so that elephant driving, once perceived as a way of life, is now increasingly perceived merely as an employment opportunity (1994: 310), albeit one that offers a modicum of status to people, many of whom would otherwise be destined to a hard life as landless labourers (1994: 303). In the light of these personnel issues, a Hattisare Education Program has been formulated with a view to the further professionalisation of Hattisares (Dhakal, 2001). The Hattisare Conservation Education Program This proposed program, still awaiting funding for its implementation, is intended to both further integrate handlers with the agendas of the park’s continuing development and to enable them to take a greater pride in their work. It is considered imperative that Hattisares understand the ecological impact of their elephants. Each day an elephant consumes 5 somewhere in the region of 200kg of fodder, which involves 2 hours of early morning grass-cutting, in addition to 5 or 6 hours open grazing within the park according to the whims of the driver. Throughout the park this adds up to roughly 16 tons of fodder removed daily for feeding, which poses detrimental impacts to the park’s biodiversity, of which the Hattisares are considered to be relatively ignorant. For example, some elephant handlers deliberately let forests burn in the mistaken belief that this allows new shoots of grass to sprout. They may also disturb important bird habitats while lopping trees for fodder, as with the Vulture which nests in the Simal tree, the most common fodder of the winter season. Hattisares (mostly Patchuwas and Mahouts) spend more time inside the park than any other park and research staff, and therefore can play a vital role in park protection and management by providing valuable information on wildlife sightings and poacher activities. The elephant staff represents an under-exploited resource in this respect, and with sufficient training they could act as frontline conservation messengers. Whilst undertaking their typical daily activities within the park, the following inputs to park management are envisaged for handlers: 6 Monitoring endangered species (rhino, tiger, elephant, bison) Preparing a daily journal of animal sightings and listing bird species Reporting on adverse environmental activities, and providing information on poaching activities (sadly on the increase since the recent escalation of political violence between Government and Maoist forces) Enabling visitors to make better wildlife sightings whilst minimising damage to flora and fauna Providing better care for domestic elephants to ensure they are healthy and happy for work Collecting fodder selectively by considering habitat protection Reporting any human activity that is offensive to the rules and regulations of the park The program would both impart to elephant staff a greater knowledge of biodiversity conservation and aim to improve standards of elephant care. Training is envisaged as being informal and participatory, with instruction by wildlife technicians, botanists, and veterinary assistants. The key components of such a training package would include: The concept of ecosystem 7 General plant ecology and physiology Seed dispersal and its importance for maintaining forest habitat Environmental considerations in selecting trees for lopping for fodder Risks associated with wild animals in their natural habitat Environmental considerations for the collection of forest products Understanding of the adverse impact of fire in grassland and forest habitats The role of Hattisares in anti-poaching and monitoring activities Better maintenance and care of domestic elephants Saving elephants from transferable diseases transmitted by domestic livestock My research has the potential to provide essential data for the effective implementation of this program by assessing current levels of understanding through the profiling of the distribution of knowledge and expertise among Hattisares, whether they are employed primarily for park or tourist activities. It is further hoped that this would also serve to highlight as-yet-unrecognised problems associated with Hattisares and their elephant handling practices, as well as the social dynamics existing between handlers and their employers. It should be noted that an uneasy 8 historical relationship obtains between Pahari and Tharu, although this is not so acute in Chitwan as in other locales such as the Dang Valley. The Tharu became victims of land appropriation and impoverishment in the wake of the malarial eradication programs of the 1950s which made the once inhospitable Tarai attractive to settlers from the hills, encouraged by the government (Guneratne 1998, McDonaugh 1997). One further aspect of the Hattisare Conservation Education Program is the intention to produce a standardised training manual, the sale of which might produce additional revenue. However, such a manual has already been produced by the Elephant Welfare Association of Kerala in conjunction with the Zoo Outreach Organisation (“Practical Elephant Management: A Handbook for Mahouts”, Namboodiri (ed) 1997), and which I believe the Nepali authorities are currently unaware of. Didactic Instruction and Apprenticeship Learning Mahout manuals and training programs can however, only function as a complement to the situated practical knowledge acquired through the participation and imitation of the neophyte apprentice. Those portions of such manuals which deal with handling skills can only provide rules-of- 9 thumb, which represent the codifications of practical experience, and which, in-and-of themselves are insufficient to master a skill (Scott 1998: 330). Such a linguistic means of imparting knowledge is constrained by its communicative mode, that of didactic instruction, which results in declarative or propositional forms of knowledge, what Ryle termed knowledge-that, whereas learning by participation and imitation results in a skills based knowledge or mastery, what Ryle termed knowledge-how (Crossley 2001: 102). To understand apprenticeship learning then requires a consideration of embodied knowledge; those forms of knowledge evident only in practice and which are highly resistant to linguistic articulation. Two key sets of intellectual resources, somewhat overlapping, but deriving from countervailing epistemologies (Cartesian and anti-Cartesian) will be considered as potential tools for the development of an account of Hattisare apprenticeship learning; firstly connectionist formulations of schema theory, and secondly Bourdieu’s practice theory, including a consideration of insights gleaned from his phenomenological predecessors. Both approaches share an associationist and enculturative conception of perception and cognition. 10 Schema Theory and Connectionism In “Language, Anthropology and Cognitive Science” Maurice Bloch argues both that Social and Cultural Anthropology have been overly preoccupied with the linguistic components of human culture, and that ethnographic research has much to offer the interdisciplinary field of Cognitive Science. Whereas Cognitive Psychology experimentally probes the nature of human cognition under controlled conditions, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) attempts to simulate human cognition (or aspects of it) in computers, anthropology conducted by participant observation allows us to examine how cognition is actually employed in natural environments. Six key contentions may be derived from his paper: 1. Much of what constitutes culture is neither linguistically formulated nor organised in language-like ways, instead largely comprising unstated, implicit knowledge (1991: 189). 2. This view of culture is attested to by ethnographic studies of apprenticeship that suggest that most learning is not a result of explicit, Socratic instruction, but is acquired through tentative participation and imitation (1991: 186). 11 3. To understand learning processes therefore requires a reconsideration of theories of thought. 4. The dominant model of thought has been that of sentential logic (simulated in AI as serial symbolic processing), a linear form of reasoning mirrored in the semantic structure of language and which effectively represents our folk-model of thought. However, this cannot account for the speed and efficiency with which we perform daily tasks and cope with familiar situations (1991: 190). 5. Instead, a connectionist theory of thought, inspired by neurological models of brain function (and simulated in AI as parallel distributed processing) can better account for the cognitive aspects of performing tasks and coping with situations. 6. If learning is not primarily linguistic in character, then active participant observation can only be endorsed as a means of approximating other peoples’ knowledge and experiences in the world. Before addressing the connectionist formulation of schema theory as presented in Claudia Strauss and Naomi Quinn’s ‘cultural models’ 12 approach (1997), it is first necessary to outline what is meant by a schema. In essence, a schema refers to implicit knowledge in the form of a network of associations that enable us to develop understandings that permit meaningful action in the world. For Casson schemas are both data structures and data processors, a pattern of action as well as a pattern for action (1983: 438), which allow us to both organise and process experience, being not merely a ‘picture’ in the mind, but also; “a kind of mental recognition ‘device’ which creates a complex interpretation from minimal inputs” (D’Andrade 1995: 136). This suggests then that; “We comprehend events in terms of the schemas they activate” (1995: 122). Alternatively, as Strauss and Quinn put it: “The essence of schema theory in the cognitive sciences is that in large measure information processing is mediated by learned or innate structures that organise related pieces of our knowledge” (1997: 49). (With regard to the identification of possible shared schemas among elephant handlers, Hart’s study in Chitwan revealed a high degree of concordance among their perceptions of the individual and social behaviour of elephants, the perceptions attributed to tamed elephants, and their interactions with drivers. It seems reasonable to attribute this to the acquisition of shared schemes of discrimination and 13 judgement). With connectionism we encounter a theory of how schematisation processes might actually operate in the human brain (Strauss & Quinn 1997: 50). Until relatively recently, as already mentioned, sentential logic has been the dominant model of thought (Bloch 1991: 190), a serial form of reasoning analogous to what Fillmore has labelled ‘checklist’ theories of necessary and sufficient conditions, in which a meaning is; “specified in terms of conjunctions of discrete properties, called variously ‘distinctive features’, ‘semantic components’ and ‘criterial attributes’” (Casson 1983: 435). In AI this sequential mode of analysis was simulated in computers by means of Serial Symbolic Processing. In this model, symbols/binary bits are the basic objects of the mind/computer. The senses/input devices bring in information from the outside world that is encoded to create a representation that is manipulated by the mind/computer using the rules of logic (as in a syllogism) or in a heuristic search (as in looking for an optimal chess move). The rules are applied serially, forming a chain of steps through which a decision is reached (D’Andrade 1995: 137). 14 Rules are symbolic representations founded in linear sequentiality, but schema theory doesn’t suggest a rule-based mode of thought, instead presupposing an indexical representation founded in holistic simultaneity (Tyler in Casson 1983: 431). To illustrate, Bloch talks of a Malagasy shifting cultivator’s ability to recognize a section of forest as potentially good land in which to make a swidden, a feat achieved near instantaneously, far quicker than would seem reasonable if this involved a cognitive process along the lines of a checklist of criterial attributes that must be fulfilled in order to identify land as good for swiddening. Instead, what seems more likely to be occurring is the matching of a mental model of a good swidden with a mental model of the particular patch of forest in question (Bloch 1991: 187). Bloch also cites his own acquired ability to recognize land good for swidden cultivation to suggest that participant observation is a good method for learning the schemas of another culture, thereby endorsing active participant observation as a valid research strategy (especially if one’s object of enquiry is apprenticeship processes). While Serial Symbolic Processing proved useful for developing chess- 15 playing and logic-solving programs, does it really serve as an adequate model of the cognitive process by which an expert chess player actually makes game moves? Dreyfus and Dreyfus found that; “what seems to distinguish the expert from the novice is not so much an ability to handle complex strategic logico-mathematical rules, but rather the possession, in memory, of an amazingly comprehensive and organized store of total or partial chessboard configurations, which allows the expert to recognize the situation in an instant so as to know what should be done next” (Bloch 1991: 188). However, the expert has not merely remembered many previous games, but developed a cognitive apparatus which enables him/her to remember many games and configurations more easily and rapidly than the nonexpert, and to draw on that experience in dealing with novel situations (Bloch 1991: 188). Bloch is arguing then; “that learning is not just a matter of storing received knowledge…but that it is a matter of constructing apparatuses for efficient handling and packing of specific domains of knowledge and practice”, and also that; “the operations connected with these specific domains not only are non-linguistic but also must be non-linguistic if they are to be efficient” (Bloch 1991: 189). 16 This pattern-recognition perspective on thought processes has been simulated in AI with parallel distributed processing networks, in which a multitude of processors acting in parallel feed information simultaneously to create a holistic synthesis (Bloch 1991: 191). Similarly, in Connectionism, a neural metaphor is used to picture knowledge. Knowledge is conceived: “not as sets of sentences but as implicit in the network of links among many simple processing units that work like neurons” and which are arranged in layers (Strauss and Quinn 1997: 51). Neurons receive excitatory and inhibitory signals from other neurons. When they work in parallel they produce intelligent action. These chemical synapses are modified by experience, and with learning, neurons undergo structural changes so that, in future, they are more or less likely to contribute to the firing of another (Strauss and Quinn 1997: 51-52). New knowledge then; “consists of changing connection weights that shift the likelihoods of what units will activate which” (Strauss and Quinn 1997: 53). This view of new knowledge and skills as resulting from the development of neural networks, as we shall see, has much in common with 17 Bourdieu’s description of learning the dispositions of the habitus, in that it also assumes that knowledge is not represented sententially in our heads, but that much learning proceeds without the need for explicitly stated rules (Strauss and Quinn 1997: 53, D’Andrade 1995: 147, Bourdieu 1977: 76). Just as habitus, in finding a middle-ground between deterministic and rational-choice approaches to action, posits a ‘regulated improvisation’ by which actors draw on prior experience to deal with novel situations, so too; “schemas as construed in connectionist models are well-learned but flexibly adaptive rather than rigidly repetitive” (Strauss and Quinn 1997: 53). The outputs of connectionist networks are improvisational because they are created on the spot, but regulated because they are guided by previously learnt patterns of association. Bourdieu’s Habitus The notion of habitus, as derived from Mauss’ essay on body techniques (1979: 97-122) has been developed in order to resolve, or at least circumvent, the tired but resilient opposition of subjectivism and objectivism and all its attendant dualities; individual/society, determinism/freedom, conditioning/creativity, conscious/unconscious (Bourdieu 1990: 25 & 55, Bourdieu 2000: 128, Crossley 2001: 82). 18 Bourdieu strives to develop a conception of human action that can account for its regularity, coherence and order without ignoring its negotiated and strategic nature, and this is what the concept of habitus is designed to achieve. “An agent’s habitus is an active residue or sediment of his past that functions within his present, shaping his perception, thought and action and thereby moulding social practice in a regular way. It consists in dispositions, schemas, forms of know-how and competence, all of which function below the threshold of consciousness…These dispositions and forms of competence are acquired in structured social contexts whose pattern, purpose and underlying principles they incorporate as both an inclination and a modus operandi” (Crossley 2001: 83). These incorporated habits do not merely dispose one to continue with particular forms of practice in particular ways, but are also resources for the generation of new practices, which in turn impact on the (everdeveloping) habitus of the agent. This emphasis on the competence, know-how, skill and disposition of the agent allies Bourdieu with proponents of phenomenological approaches. His crucial criticism of, and point of divergence from these approaches 19 however, lies in their apparent failure to locate the interpretive horizon of the agent in the structural context from which it emerges. Although no one agent’s habitus will be identical to that of any other’s, Bourdieu considers individual biographies as but strands in a wider collective history. “An individual habitus is but a variant of a collective root” (Crossley 2001: 84). The system of dispositions and schemas that constitute any one habitus is considered a structural variant of larger group or class habituses, expressing the difference between the trajectories or positions inside or outside the various classes which influence the composition of one’s habitus. Two further terms from Bourdieu’s ‘conceptual tool kit’ are required to better understand the conditioned and conditioning relation of the agent’s habitus to its social environment; that of field and capital. While habitus accounts for the dispositions, schemas, and competencies that both generate and shape action, field provides the context for action, or the parameters of possibility, while capital provides the resources available to the actor within that context, or that which shapes the parameters of possibility. 20 For Bourdieu, modern societies are differentiated into interlocking fields, some of which coincide with institutions such as the family, the media, and academia, but which can also assume sub and trans-institutional forms. These fields are constituted through competitive exchanges of goods (taken in its widest possible and potentially abstract sense) that are deemed valuable within that field. The field of elephant handling for instance might be characterised in terms of competition for a rank and prestige rooted in experience, skill and mastery of elephants. The hattisare who is called on to perform complex and demanding operations (such as the Phanit’s role in the corralling and capture of Rhinos chosen for translocation, or in dealing with elephants in the dangerous state of musth) will be someone recognised as possessing those qualities which most closely conform to the prototypic schema of the ideal handler. Bourdieu’s account of the activity of agents competing for capital within a field draws on the rich metaphorical resource of ‘the game’, in which ‘players’ have a stake or interest, which Bourdieu is fond of referring to as illusio; by which he means the pursuit of goals and the adherence to norms and distinctions appropriate to its field. So, a dynamic and dialectical relation obtains between habitus and field. “Agents’ actions 21 are shaped both by their habitus and by the exigencies and logic of ‘the game’ as it unfolds” (Crossley 2001: 87). Capital is what is at stake when an agent operates according to the parameters for action given by a field. “Anything may count as capital that is afforded, however tacitly, an exchange value in a given field, and that thereby serves both as a resource for action and as a ‘good’ to be sought after and accumulated” (Crossley 2001: 87). This amounts to what I term a multi-valent theory of capital. “In addition to financial capital, Bourdieu lists as the main forms of capital: symbolic capital (i.e. status); social capital (i.e. useful contacts and networks); and most famously, cultural capital, which may manifest in the form of educational qualifications, ‘tasteful’ dispositions and manner, or the possession of highly regarded artefacts and goods” (Crossley 2001: 87, my italics). For Bourdieu it is one’s capital assets that largely define one’s social position, in turn determining the conditions that shape one’s life experiences and thus also one’s habitus. And the various forms of capital depend on agents’ (mis)recognition for their value and power. “They are all, to a degree, valuable because we agree that they are valuable” (Crossley 2001: 87). Being rooted in habit, they are seldom 22 identified as consensual agreements at all. “like footballers involved in a game, social agents must perceive and treat (misrecognise) the arbitrary framework of social fields as real and natural if they are to play effectively” (Crossley 2001: 93, see also Bourdieu 1990: 68). Analogues of Habitus in Husserl and Merleau-Ponty In “The Phenomenological Habitus and its Construction” Nick Crossley argues that the phenomenology of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty provide a broader and deeper understanding of habituation than is available in Bourdieu’s accounts, in particular, by focusing on Husserl’s notions of typification and pairing, and Merleau-Ponty’s corporeal schema. His critique of Bourdieu is not so much substantive as it is a concern with matters of emphasis in his expositions. Bourdieu’s insistence on habitus is considered to pre-empt his conception of agency by his failure to sufficiently remind us that the habitus is a property of agents: It is not habits that act but agents, not habits that improvise but agents, and not habits that act strategically but agents. Thus, the generative role of agency appears to be underplayed, making him vulnerable to charges of determinism. In addition, Crossley contends that the sociological vision usurps the philosophy of the subject, claiming: “His work…offers us 23 relatively little in the way of an analytical toolbox for opening up and exploring the subjective side of the social world. The concept of the habitus hints at the possibility for a hermeneutic dimension to social analysis but sadly does no more than hint” (2001: 98). “Merleau-Ponty’s exploration of the nature of habit is rooted in his broader analysis of human embodiment and agency. Arguing against Cartesian mind/body dualism and a variety of forms of idealist philosophy, he seeks to establish the irreducibly embodied nature of human subjectivity and agency” (Crossley 2001: 99). In the Cartesian tradition the body is merely an appendage of the mind, but for MerleauPonty we are our bodies! Merleau-Ponty wishes both to avoid idealist views of a disembodied mind as well as mechanistic views of consciousless bodies (as in the stimulus/response of psychological behaviourism), just as Bourdieu wishes to avoid the either/or option of subjectivist and objectivist explanations by means of reasons (Rational Choice Theory) or causes (Structuralism) (Bourdieu 2000: 139, 1994: 133). Where Descartes and Kant explained meaning and action by recourse to 24 the reflective acts of a transcendental ego, Merleau-Ponty argues that our primary relation to the world is one of practical involvement and mastery. “Our primary manner of being is not ‘I think’ as Descartes suggests, but rather ‘I can’ or ‘I do’” (Crossley 2001: 100). Since one is one’s body, one does not therefore relate to it as an external object as Descartes’ thinking implies. If I move my arm it does not require a prior intentional thought. The act is intentional, but not in the sense that the action is added to or caused by that intention. As with Maurice Bloch’s contentions, such an intentional act need not be formulated either linguistically or reflectively. This involves knowledge, but not in the intellectualist sense, as with Ryle’s distinction between the discursive knowledge-that and the embodied knowledge-how. Rather, as Bourdieu would put it, it is a doxic knowledge; knowledge that does not require conscious formulation, but which ‘fits’ the exigencies of the circumstances, and which may also be characterised as functional and ‘interested’. Furthermore: “It is not only my own body that I ‘know’ in this way, moreover. I have a pre-reflective sense or grasp on my environment, relative to my body, as is evidenced by my capacity to move around in and utilise that space without first having to think how to 25 do so” (Crossley 2001: 101). “It is this fundamental coordination of the embodied agent with both self and world that lies at the root of Merleau-Ponty’s conception of the corporeal schema. The corporeal schema is an incorporated bodily knowhow and practical sense; a perspectival grasp upon the world from the ‘point of view’ of the body (Crossley 2001: 102). Crossley illustrates this idea of incorporation by means of the example of driving a car, but one could just as easily use the example of driving an elephant. Over time one incorporates a sense of the dimensions of the car or elephant, so that one comes to adopt an extended point of view in which the car or elephant acts as a prosthesis of the body, an extension to one’s corporeal schema. The corporeal schema is considered the active ingredient of agency, situating agents perceptually, linguistically, and through motor activity. Of course, a key difference between the examples of driving a car and an elephant concerns the sentience of the elephant, and hence the possibility of intersubjectivity between driver and elephant. Indeed, in interpreting Merleau-Ponty, Crossley argues that this bodily sense is also of fundamental relevance to social interactions, providing the grounding for 26 intersubjectivity. “Just as we can incorporate the dimensions of a car within our corporeal schema, we can incorporate a social group” (Crossley 2001: 103). Similarly, and also drawing on Merleau-Ponty, Sheets-Johnstone also argues that intercorporeality provides the basis for intersubjectivity (c.f. 2000). Just think of the way we talk of ‘esprit de corps’ to capture the sense of solidarity that develops in social movements or among various constituencies who share some defining interest. “The agent thinks, in these cases, from the point of view of the group. The group bestows a collective power upon its members and each member feels and wields this power, perhaps unknowingly, in individual actions” (Crossley 2001: 103). Habit, formulated in contradistinction to the conditioned reflex posited by traditional behaviourists, acts as an addition to the corporeal schema. “Habit involves a modification and enlargement of the corporeal schema, an incorporation of new ‘principles’ of action and know-how that permit new ways of acting and understanding. It is a sediment of past activity that remains alive in the present in the form of the structures of the corporeal schema; shaping perception, conception, deliberation, emotion, and action” (Crossley 2001: 104). Habit is conceived then as a form of 27 embodied and practical understanding, manifesting as competent and purposive action, a knowledge-in-action, only evident in its performance. The key implication of relevance here, is that we learn not so much by thinking as by doing. By drawing on Husserl’s thinking about apperception, Crossley also argues that habits do not merely regulate the way we act, but also shape the ways in which we make sense of our environments. Husserl’s writings serve to remind us of the extent to which action in the world is guided by habituated expectation. All perception is perspectival and hence partial, requiring us to tacitly impute ‘hidden’ qualities or dimensions, to ‘fill in the gaps’ in order to develop a seeming perception of the whole (as with the implicit knowledge of schemas which provide the framework with which to make sense of situations). Husserl identifies two closely linked processes of apperception which he refers to as typification and pairing. “Typification entails the formation of habitual perceptual schemas that simplify complex perceptual input. In effect the uniqueness and particularity of each new moment of our experience is simplified by being subsumed into a general category or 28 ‘type’. Thus, even when we approach objects that, strictly speaking, we have never encountered before, we will see them in terms of the broader type to which they belong. Moreover, newly typed objects are ‘paired’ with objects of the same type that we have experienced in the past, and properties and qualities attributed to them accordingly” (Crossley 2001: 109). So, as with Bourdieu’s habitus, and Strauss and Quinn’s cultural models, perceptual experience is shaped by biographically acquired habit. Lived experience may disappear from conscious recall, but will remain latent, sedimented in the form of habitus, and ready to be reawakened by an active association, disposing the agent to respond in ‘typical’ ways to ‘typical’ situations. In sum, sedimented experience contributes to the constitution of the habitus/corporeal schema through the associational processes of typification and pairing which shape the perceptual schemas by which one both makes sense of, and acts upon the world. Reiterating a point already made in the discussion of Bourdieu’s Logic of Practice: “Typifications and pairing, as well as know-how and agentic dispositions more generally, usually arise out of social interactions within 29 collectivities and, as such, tend to be shared. Most aspects of our individual habitus, as Bourdieu has done most to show, are rooted in the shared habitus of the groups to which we belong” (Crossley 2001: 110). Finally, such phenomenological stances attempt to provide an alternative to determinist accounts of human social life. For they suggest that human behaviour is not so much determined by external events as it is engaged by them, replying purposively to its environment in accordance with the meanings that environment has for the agent, meanings which have been shaped by the acquired schemas and dispositions of the habitus. In that habits are considered a residue of action, they also function as a testament to agency. Ontogenetic Foundations of Apprenticeship Learning In the preceding discussion, habituation has been presented as deriving from both innate and acquired sources, and as being ‘durably installed’ (Bourdieu 1990: 57). Maxine Sheets-Johnstone has suggested that some of the most fundamental acquired dispositions of relevance to accounts of apprenticeship learning may be found in child development, specifically 30 referring to joint attention, imitation and turn-taking (2000: 343). Joint visual attention is about ‘looking where someone else is looking’, a shared focus in other words. Non verbal communicative efforts stemming from joint attention can be recognised by a clear and codifiable set of behaviours, namely; head orientation, visual gaze, and vocalisations coupled with one-fingered pointing gestures. Joint visual attention is then, the first step toward a ‘meeting of minds’. Already then it can be seen that the intersubjectivity essential to apprenticeship learning is more fundamentally grounded in an intercorporeal awareness, an awareness that includes not just a sense of one’s own body and that of another, but also of agency and intentionality. Sheets-Johnstone then relates these insights to examples of apprenticeship learning in adult life, citing Akre and Ludvigsen’s study of how physicians develop professional knowledge and skills in their daily work. “A foundational capacity to focus on the same object with another person and to be aware both of what the person does with respect to the object and of the meaning the other person attaches to what he or she is doing with the object is at the core of medical practice. In sum, the skill of a 31 physician has its epistemological roots in ontogeny, in the communal act of shared attention, in the transfers of sense that are part and parcel of the sharing, and in the active and semantically resonant kinetic-tactilekinaesthetic bodies that are its foundation” (2000: 350). In as much as apprenticeship is not just learning in a purely instrumental sense, but also involves socialisation, then, when considering the range of its current and historical implementations, one becomes aware of the often authoritarian and oppressive character of apprenticeship learning. Joint attention is considered to engender; “certain social values and certain cultural groomings through the bodily comportments and vocalisations of actively participating mothers and caretakers. Apprenticeship learning in adult situations is socially saturated in basically similar ways” (Sheets-Johnstone 2000: 351). Sheets-Johnstone goes on to cite Jean Lave’s work in which learning is portrayed as ‘situated activity’ that cannot be reduced to merely formal didactic training, and in which (drawing on Bourdieu) practice is a matter of adjusting to institutionally structured possibilities for action. Lave’s concern with learning through participation functions as an implicit 32 testimonial to shared attention since participation entails common focus and involvement. With regard to imitation, the work of psychologist Andrew Meltzoff is utilised to argue that infants as young as two or three weeks old imitate adult tongue protrusions, mouth openings, and lip protrusions, subsequently concluded to be an ability present from birth. While his research hinges on reductive explanation by recourse to ‘entities’ postulated as key mechanisms, Sheets-Johnstone is more concerned with understanding imitation experientially as a developmental phenomenon. By extending this kinetic thematic as elaborated in her treatment of joint attention, infant imitation may be seen as an example of kinetickinaesthetic matching, a matching that isn’t so much achieved through the establishment of some representational schema or other hypothetical entity, as it is from the primal animation which resonates through the tactile-kinaesthetic body. Finally we come to turn taking. “Turn-taking is uniformally recognised by child psychologists as a precursor of language” (Sheets-Johnstone 33 2000: 362). The alternating pattern of smiling and vocalising between mother and child serves as the principal lesson in turn taking, the cardinal rule for all later discourse between two or more people. So, the ontogenetically acquired dispositions of joint attention, imitation and turn-taking are seen to serve to shed light on the learning of nonrepresentational knowledge that is ‘etched’ as it were, in the body. The Dilemma of Operationalisation In this final section I consider some of the difficulties of methodologically applying these insights to apprenticeship learning. Bourdieu’s theory of practice seems to supply a hermeneutic perspective, which, as such, does not allow a simple empirical verification of his insights. This is acknowledged in his critique of the structuralist tendency to confuse ‘models of reality’ with the ‘reality of models’ (Bourdieu 1990: 39). For the structuralist derives rules from the study of the regularities of social practice and then accords those rules an explanatory status in accounting for them (Crossley 2001: 82, Bourdieu 1994: 133). This could only be countenanced if the synoptic vision which Bourdieu attributes to those who make such an epistemocentric fallacy’ were 34 possible, by which is meant the assumption that one can step outside of a situated perspective. But Bourdieu does not automatically accord the social scientist such an epistemological privilege (indeed he has been an ardent advocate of encouraging epistemic reflexivity as an essential part of academic practice). Rather, he suggests that the social scientist is better placed than most to strive to identify the objective conditions which influence one’s habitus since his/her field provides the interest (illusio) to do so, aided by the use of specialised research methods (Crossley 2001: 93-94). Similarly, Strauss and Quinn concede that the schemas they derive from their research are inferred, and as such are analytic constructs. However, the ‘cultural models’ approach of Strauss and Quinn seems to offer a clearer picture of how these theoretical insights might be applied; by means of discourse analysis. In my own research, with its greater concern for embodied forms of knowledge, I intend to utilise data gathered through the use of digital video. By replaying footage of various Hattisare task performances to key informants, it is hoped that the commentary they supply will be useful in training and directing my attention toward the acquired bodily skills of managing tame elephants. 35 Bibliography Bloch, M 1991 Language, Anthropology and Cognitive Science Man 26(2): 183-198 Bourdieu, P 1977 Outline of a Theory of Practice Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Bourdieu, P 1990 The Logic of Practice Oxford: Polity Press Bourdieu, P 1994 The Scholastic Point of View in Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action Oxford: Polity Press Bourdieu, P 2000 Pascalian Meditations Oxford: Polity Press Casson, R 1983 Schemata in Cognitive Anthropology Annual Review Of Anthropology 12: 429-462 Coy, M 1989 Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again Albany: State University of New York Press Crossley, N 2001 The Phenomenological Habitus and its Construction 36 Theory and Society 30(1): 81-120 D’Andrade, R 1995 The Development of Cognitive Anthropology Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Dhakal, N (n.d) Hattisare Conservation Education Program Nepal Conservation Research and Training Centre Fernando, S 1989 Training Working Elephants in UFAW(ed) Animal Training: A Review and Commentary on Current Practice Potters Bar: UFAW Guneratne, A 1998 Modernization, The State, and the Construction of a Tharu Identity in Nepal Journal of Asian Studies 57(3): 749-773 Guneratne, A 2001 Shaping the Tourist’s Gaze: Representing Ethnic Difference in a Nepali Village Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (n.s) 7: 527-543 Guneratne, A 2002 Many Tongues, One People: The Making of Tharu Identity in Nepal London: Cornell University Press Hart, L 1994 The Asian Elephants-Driver Partnership: The Drivers Perspective Applied Animal Behaviour Science 40: 297-312 Hart, L & Sundar 2000 Family Traditions for Mahouts of Asian Elephants Anthrozoos 13(1): 34-42 Krausskopf, G & Meyer, P 2000 The Kings of Nepal and The Tharu Of The Tarai; The Panjiar Collection of Fifty Royal Documents Issued From 1726-1971 Los Angeles: Rusca Press McDonaugh, C 1997 Losing Ground, Gaining Ground: Land and Change In a Tharu Community in Dang, West Nepal in Gellner, D, PfaffCzarnecka, J & Whelpton, J (eds) Nationalism and Ethnicity in a 37 Hindu Kingdom: The Politics of Culture in Contemporary Nepal Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers Namboodiri, N (ed) 1997 Practical Elephant Management: A Handbook For Mahouts Kerala: Elephant Welfare Association Scott, J 1998 Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve The Human Condition Have Failed London: Yale University Press Sheets-Johnstone, M 2000 Kinetic Tactile-Kineasthetic Bodies: Ontongenetical Foundations of Apprenticeship Learning Human Studies 23: 343-370 Strauss, C & Quinn, N 1997 A Cognitive Theory of Cultural Meaning Cambridge: Cambridge University Press