marco pedrazzi-eng

advertisement

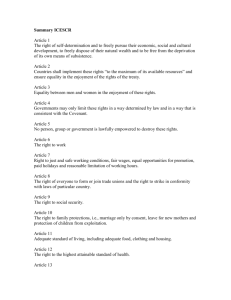

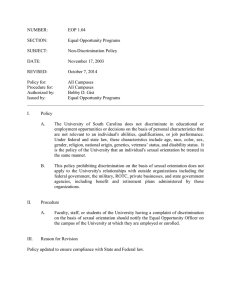

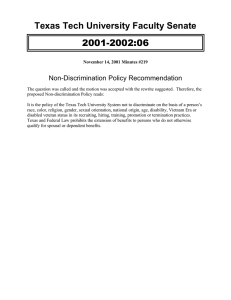

EU-China Network Seminar on Human Rights Right to health/Right to social security University of Essex, Colchester, U.K., 27-28 April 2004 International standards on the right to health and non-discrimination by Marco Pedrazzi 1. Introduction. The right to health has many dimensions. The aim of this paper is to have a look at the basic international standards relating to the right to health through the lens of one of these dimensions, i.e. the principle of non-discrimination. Although the right to health is enunciated in various fundamental international instruments, starting with the Constitution of the World Health Organisation (WHO), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), its precise content is not yet entirely clarified. The difficulty in elaborating an appropriate definition is also due to the amplitude of the concept of health, and to the multiple connections of the right to health with other fundamental rights. However, international treaty monitoring bodies have given in recent years important contributions to the definition of this content: I refer first and foremost to General Comment n. 14 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) of 11 August 2000. A further contribution is presently given by the reports of the Special Rapporteur on the right to health nominated by the Commission on Human Rights. Both the Committee and the Rapporteur place a high emphasis on the principle of non-discrimination, underlining its relevance for the realisation of the right to health. Non-discrimination is obviously not “the feature” characterising the right to health as such and permitting to distinguish it from other fundamental human rights. The “right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”, as enunciated in ICESCR, Art. 12, has been specified by CESCR, in general terms, as “a right to the enjoyment of a variety of facilities, goods, services and conditions necessary for the realization of the highest attainable standard of health” 1. It has been further clarified as a right containing both freedoms and entitlements: “The freedoms include the right to control one’s health and body, including sexual and reproductive freedom, and the right to be free from interference, such as the right to be free from torture, non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation. By contrast, the 1 CESCR, The right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), General Comment n. 14 (2000), UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4, 11 August 2000, par. 9. 1 entitlements include the right to a system of health protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highest attainable level of health”2. Already from this first approximation of the content of the right to health, the fundamental role of the principle of non-discrimination appears quite clearly. If we consider the freedoms’ aspect, State (or private) interferences with the right to control one’s health and body are quite generally the product of discriminatory practices, be the discrimination against women, against children, against detainees or any other category. If we consider the entitlements’ aspect, the system of health protection has to provide, by definition, “equality of opportunity” for all individuals and groups: that is to say, opportunity for all, without discrimination. 2. Non-discrimination as an essential dimension of international standards on the right to health. The non-discrimination dimension of the right to health is unequivocally spelled out in all basic international instruments referring to this right3. Firstly, the principle of nondiscrimination is implicit in the words used to enunciate the right: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including… medical care…” (Art. 25, UDHR); “The States Parties… recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” (Art. 12, ICESCR). By definition, the right to health is a fundamental human right which is not pertaining to citizens, or to specific sectors of the population, but to every human being: that means that every individual must be given equal opportunities to develop the highest attainable standard of health, without exception. Secondly, the fact that the enjoyment of the right to health has to be guaranteed without discrimination is specifically provided for in the non-discrimination clauses, contained in the same instruments, and with which the articles I just referred to must be read in conjunction. Art. 2, UDHR states: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. In similar terms, Art. 2.2, ICESCR states: “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. 2 Ibid., par. 8. That is already clear in the first international enunciation of the right, in the Preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organisation of 22 July 1946: “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition”. 3 2 Where it is clear that the prohibited grounds for discrimination are not exhaustive4: we can mention, among other prohibited grounds, age, sexual orientation, disability, health, as it is known that, paradoxical as it may be, even the fact of being struck by certain diseases, which in the common perception are associated with a social stigma, becomes a ground for curtailing fundamental rights of the individual, and among them the right to health5. A specific additional provision, Art. 3, ICESCR, is dedicated to ensuring “the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all economic, social and cultural rights” set forth in the Covenant, including the right to health. Articles 2 of both UDHR and ICESCR contain a general prohibition of discrimination. However, general prohibitions are not sufficient when we are confronted with the need to protect and to implement equal rights and opportunities for vulnerable categories and groups. That is why a whole set of instruments provides for specific measures in order to promote the equal enjoyment of, specifically or inter alia, the right to health of various categories or groups of people. The 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the 1989 International Convention on the Rights of the Child, the 1989 ILO Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, the 1990 International Convention on the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, the various principles and standards elaborated in the framework of the United Nations or in other fora relating to the rights of persons with disabilities, of older persons, of persons in a state of detention, of persons with mental illness, of persons affected by HIV and AIDS patients, are, among others, designed to prevent discrimination and to build up an effective possibility of equal enjoyment, de jure and de facto, of the right to health by the considered categories or groups6. 3. Non-discrimination as a fundamental right. Obviously, non-discrimination has a yet wider application in international human rights law, as it can be said to be not only a principle necessarily characterising the enjoyment of all fundamental rights, but the content of an autonomous fundamental right not to be discriminated in any circumstance, and particularly in the enjoyment of any right (and not only fundamental ones) provided for by the State. This fundamental right to nondiscrimination is enshrined, inter alia, in Article 26 of the International Covenant on 4 See, inter alia, the Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN Doc. E/CN.4/1987/17), at par. 36. 5 See CESCR, General Comment n. 14, note 1 above, at par. 18; The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Report of the Special Rapporteur, Paul Hunt, submitted in accordance with Commission resolution 2002/31, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2003/58, 13 February 2003, at par. 59 ff. 6 See, inter alia, the 1991 United Nations Principles for Older Persons, the 1991 UN Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness, the 1993 UN Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. Many of the relevant documents are reproduced in G. Alfredsson and K. Tomaševski, A Thematic Guide to Documents on Health and Human Rights, The Hague/Boston/London, 1998. 3 Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and in Protocol n. 12 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which has not yet entered into force. It is also worth noting that the above-mentioned provisions are useful in such as they open the possibility of controlling respect of at least some basic components of the right to health, or related rights, by means of the international mechanisms designed for the protection of civil and political rights: as underlined by the Human Rights Committee (HRC) in a case involving social security benefits, Article 26, ICCPR, does not of itself “for example, require any State to enact legislation to provide for social security. However, when such legislation is adopted in the exercise of a State’s sovereign power, then such legislation must comply with article 26 of the Covenant”7. It is to be hoped that the entry into force of Protocol n. 12, ECHR, will give an impetus to developments of the kind also in front of the European Court of Human Rights, which has already given other examples of how the right to health or related rights can be protected under the umbrella of civil and political rights8. 4. Non-discrimination and the essential elements of the right to health. I will now come to examine some of the main components of the right to health, as elaborated by CESCR, under the lens of the principle of non-discrimination. I will start with the “essential elements” of the right to health as determined in General Comment n. 14: availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality. 4.1. Availability. As stressed by the Committee: “Functioning public health and healthcare facilities, goods and services, as well as programmes, have to be available in sufficient quantity within the State party”9. Facilities include underlying determinants of health, such as safe and potable drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities. Availability does not contain of itself the requisite of non-discrimination. However, “available” means “capable of been made use of”10. If this capability were to be only theoretical, or open only to some sectors of the population, the right to health of people could not be said to be guaranteed. 4.2. Accessibility. That is why the requisite of accessibility is so important, and here the principle of non-discrimination fully emerges as a fundamental aspect of the whole issue. Accessible means, in fact, “accessible to all, especially the most vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population, in law and in fact, without discrimination on any of the prohibited grounds”. Accessibility has various facets. First of all, it implies that there shall not be any legal limitation, proscribing access to health care facilities by particular subjects or groups, for example foreigners, or people belonging to certain 7 Communication n. 182/1984, F.H. Zwaan-de Vries v. Netherlands, HRC Views, 9 April 1987, par. 12.4. 8 See, inter alia, the use of Art. 8, ECHR, on the right to respect for private and family life, in the cases Lopez Ostra v. Spain (judgment of 23 November 1994) and Guerra and others v. Italy (judgment of 19 February 1998). 9 This and the following quotations are taken from General Comment n. 14, note 1 above, par. 12. 10 Collins English Dictionary, Glasgow, 1998. 4 minorities. But domestic law is required much more, in terms of positive measures to overcome de facto discrimination or to prohibit discrimination by non-State actors. One form of de facto discrimination which the State shall endeavour to eliminate consists of the limits on physical accessibility which can penalise, for example, rural communities situated far away from all the main health facilities, or people with disabilities, who often don’t have physical access to facilities because of architectural barriers. Another situation requiring the State to intervene is given by obstacles to economic accessibility, or “affordability”: a fundamental requirement is that “health facilities, goods and services must be affordable to all”. A requirement that can be implemented in different ways, but which imposes that the burden of economic contributions to health care shall not be out of proportion with regard to the individual’s or family income and that individuals who are not able to pay shall not pay for health care. A last essential facet is information accessibility. Access to adequate information is essential for the prevention of a great number of diseases and health-related problems, especially as far as sexual and reproductive health are concerned: also in this case non-discrimination plays a fundamental role, as the possibility of access to information is often restricted in relation to women or other categories, such as adolescents or rural communities11. 4.3. Acceptability. Also cultural acceptability has a relationship with nondiscrimination, as health facilities, goods and services that are not culturally acceptable to a certain community, for example an indigenous population, will de facto prevent the attainment of good health standards by the members of that community, thereby ending in discrimination against them. 4.4. Quality. The last essential element envisaged by the Committee is quality. That means that health facilities, goods and services shall be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality. The principle of non-discrimination has a strict relationship with quality: the excellent quality of some medical facilities will prove to be discriminatory if only the rich or only some sectors of the population have access to them. Good quality means quality for everyone, without discrimination. 5. Non-discrimination and States’ general obligations. CESCR has classified general obligations of States parties in three different categories or levels: obligations to respect, to protect and to fulfil12. I will now read those three levels of obligations through the lens of the principle of non-discrimination. 5.1. Obligation to respect. The obligation to respect basically imposes a duty of abstention on the part of the State. The State shall, for example, refrain from unlawfully polluting air, water and soil, thereby releasing substances dangerous for human health. It shall refrain from applying coercive medical treatments, unless on an exceptional basis for the treatment of mental illness or the control of communicable diseases. It shall refrain “from limiting access to contraceptives and other means of maintaining sexual 11 See The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Report of the Special Rapporteur, Paul Hunt, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2004/49, 16 February 2004, par. 32 ff. 12 See General Comment n. 14, note 1 above, at par. 33 ff. 5 and reproductive health, from censoring, withholding or intentionally misrepresenting health-related information”. It shall refrain from denying or limiting equal access to health services for all persons. It is not necessary to stress how this last requirement can be translated into a duty of non-discrimination. I will just give a short example. States shall not deny or limit access to health facilities, goods and services for foreign immigrants. In regulating access to medical care for immigrants, States shall abstain from imposing requirements rendering their enjoyment of the right to health more difficult in practice. In Italy, foreign immigrants with a regular residence permit have access to the public health system on an equal footing with citizens. Illegal immigrants have access to essential medical care, at no cost, if they are not able to pay; and the medical personnel shall not signal them to the public authorities for the only reason they don’t have a residence permit: a different rule would in fact keep them away from acceding to health facilities13. All this is very good, and in fact the situation has probably improved in the last few years; but practical implementation is another question, and even the requirements conceived for the access to health care of legal immigrants do not adequately take into account their needs and end up imposing on them many obstacles on the road to a real equalisation with citizens14. If the last mentioned situation has typically to do with non-discrimination, the principle of non-discrimination can have a relevant bearing also on the other aspects mentioned before: for example, often coercive medical treatments are applied on some basis of discrimination; the limitation on access to information, especially in the sexual and reproductive health areas, often especially harms women, adolescents or other vulnerable groups. 5.2. Obligation to protect. “Obligations to protect include, inter alia, the duties of States to adopt legislation or to take other measures ensuring equal access to health care and health-related services provided by third parties”. A typical and fundamental component of these duties bears on the prohibition of discriminatory practices by private entities: an essential task in an epoch of growing privatisation of health services. To protect the right to health also involves taking all possible measures to prevent violence against vulnerable groups, such as women, children, older persons: violence which is of itself discriminatory15. It involves taking measures to proscribe harmful traditional practices, as female genital mutilations or forced marriages. 5.3. Obligation to fulfil. This obligation requires States to adopt a whole series of positive measures to realise, at the highest attainable level, the right to health of all individuals and groups. This implies, in particular, actions directed towards vulnerable groups, in order to remove de facto obstacles preventing or limiting their access to all health facilities, goods and services and their full enjoyment of their right to health, 13 On the problems relating to the access to health care of illegal immigrants see B. Toebes, “The Right to Health”, in A. Eide et al. (eds.), Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2nd ed., p. 169 ff., at p. 187 ff. 14 See P. Bonetti and M. Pastore, “L’assistenza sanitaria”, in B. Nascimbene (ed.), Diritto degli stranieri, Padova, 2004, p. 974 ff. 15 See, inter alia, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2004/49, note 11 above, par. 81 ff. 6 thereby eliminating the roots of discrimination. The Committee has spelled out three different facets of the obligation to fulfil: the obligation to facilitate, requiring States, inter alia, to take positive measures to assist individuals and communities to enjoy the right to health; the obligation to provide the means to realise the right to health when individuals or groups are unable to realise it themselves; the obligation to promote the right to health, for example “ensuring that health services are culturally appropriate and that health care staff are trained to recognize and respond to the specific needs of vulnerable or marginalized groups”. All those actions contribute in eliminating or at least limiting discrimination. 6. Non-discrimination and international cooperation. The principle of non-discrimination plays an essential function not only in the definition of the duties that a State owes to the people living or temporarily happening to be under its jurisdiction, but also of the duties of States in the conduct of their international relations. Under the Charter of the United Nations, Member States “pledge themselves to take joint and separate action in co-operation with the Organization” (Art. 56) for the promotion, inter alia, of “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion” (Art. 55 c.). Art. 2.1, ICESCR, provides that each State Party “undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, … to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures”. Policies of rich States preventing the populations of poorer countries from acceding to essential medicines and other health facilities and services (or permitting non-State actors to do so), and thereby contributing to a heavy discrimination against a huge percentage of the world population, are clearly incompatible with these provisions. It is hopeful that the efforts currently under way to improve the worldwide access to essential medicines will produce some effective results16. But the above-mentioned provisions should also be read in a more positive way, as placing on all countries, according to their possibilities, the burden of improving opportunities for all people in the world to realise their right to health, therefore actively contributing to the eradication of a discrimination which is effectively hindering the enjoyment of such a fundamental right in large areas of our planet17. One way of implementing this positive duty would consist in finding the means to promote research on neglected diseases18. 16 On the whole issue see The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Report of the Special Rapporteur, Paul Hunt, Addendum, Mission to the World Trade Organization, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2004/49/Add.1, 1 March 2004, especially at par. 41 ff. 17 See CESCR, General Comment n. 3, 14 December 1990 (UN Doc. E/1991/23), at pars. 13 and 14. See also the Limburg Principles, note 4 above, par. 29 ff., and the Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Maastricht, 22-26 January 1997), at par. 15 (j), where the “failure of a State to take into account its international legal 7 7. Conclusive remarks. The relationship between the right to health and the principle of non-discrimination has many dimensions: I have only mentioned some of them, and in general terms. The principle of non-discrimination imposes on States obligations of a negative and of a positive content: they require States, first of all, to abstain from imposing on certain groups limits or prohibitions affecting their access to the right to health; they then require the adoption of multiple measures directed to prohibit discrimination by third parties; and other active measures through which States have to promote equality by eliminating de facto obstacles which prevent the enjoyment of the right to health by the vulnerable sectors of society. An equally, if not more radical action is required on the international plane. Respect for the principle of non-discrimination, especially, but not only, in its negative dimension (duty to abstain from discrimination, duty to prohibit discrimination) is the object of sufficiently precise legal obligations which are naturally justiciable in front of national, and international, courts. However, judicial and nonjudicial methods for assessing violations, enforcing accountability and providing remedies need to be developed both on the national and on the international scale. obligations in the field of economic, social and cultural rights when entering into bilateral or multilateral agreements with other States, international organizations or multinational corporations” is mentioned among the examples of violations of the rights in question. With regard to the right to health see CESCR, General Comment n. 14, note 1 above, par. 38 ff. 18 See P. Hunt, “Neglected diseases, social justice and human rights: some preliminary observations”, paper presented at the International Workshop on Intensified Control of Neglected Diseases, Berlin, 10-12 December 2003 (draft circulated by the author). 8