Final Draft

advertisement

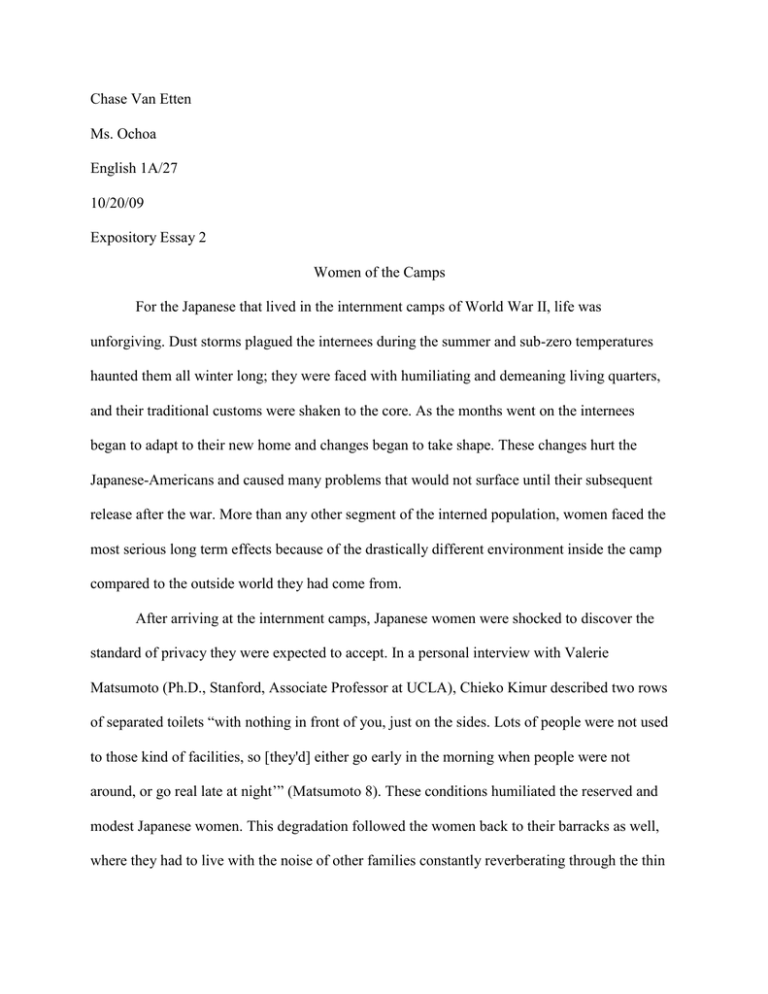

Chase Van Etten Ms. Ochoa English 1A/27 10/20/09 Expository Essay 2 Women of the Camps For the Japanese that lived in the internment camps of World War II, life was unforgiving. Dust storms plagued the internees during the summer and sub-zero temperatures haunted them all winter long; they were faced with humiliating and demeaning living quarters, and their traditional customs were shaken to the core. As the months went on the internees began to adapt to their new home and changes began to take shape. These changes hurt the Japanese-Americans and caused many problems that would not surface until their subsequent release after the war. More than any other segment of the interned population, women faced the most serious long term effects because of the drastically different environment inside the camp compared to the outside world they had come from. After arriving at the internment camps, Japanese women were shocked to discover the standard of privacy they were expected to accept. In a personal interview with Valerie Matsumoto (Ph.D., Stanford, Associate Professor at UCLA), Chieko Kimur described two rows of separated toilets “with nothing in front of you, just on the sides. Lots of people were not used to those kind of facilities, so [they'd] either go early in the morning when people were not around, or go real late at night’” (Matsumoto 8). These conditions humiliated the reserved and modest Japanese women. This degradation followed the women back to their barracks as well, where they had to live with the noise of other families constantly reverberating through the thin walls. Inside these small spaces the Japanese women were expected to carry out some semblance of a normal life. All in the same room they would cook, clean, hang their laundry, and try desperately to maintain a family life. These circumstances led to women facing higher pressures from their surroundings than any other segment of the population. Small children and teenagers found solace in their peers; the men that were at the camps spent much of their time together; the women were left to go about daily activities that had once been easy but now stretched their coping abilities to the limit. Some of the younger, childless women were able to find leisure time among the mounting stresses and better themselves in a number of ways. Not all of the long term effects felt by the detained Japanese women were negative. Since immigrating to the US, these women had been limited in the jobs they were allowed to hold; it was difficult to find work as anything other than a farm laborer or a domestic service provider. While in the camps, women could apply for any job that was offered and were paid the same low wages as men. In a newspaper printed by internees at Topaz, Utah entitled The Topaz Times, director of the Center Service departments, George A. Greens, is quoted as saying, “that this policy of employment has been adopted in order to give qualified persons equal consideration for work as openings occur” (par. 5). Women were able to apply for jobs ranging from accounting to agriculture, and from medical care to journalism. They also had the option to take adult night classes in which they could learn arts such as calligraphy, wood carving, and tailoring. Once these women began relocation after the camps closed, they entered into various jobs that had been unavailable to them before. They were hired quickly because of the labor shortage and were accepted into many vocational schools and universities. The time spent in the internment camps allowed Japanese women to break away from traditional jobs and gain more independence. This new found autonomy correlated to the declining intimacy of family kinship which had already been strained from the internment process. The environment at the camps was chaotic at times and weakened family ties. Julie Otsuka describes one daughter’s change in her novel, When the Emperor Was Divine. This young girl begins to break away from her mother and brother as she becomes more peer oriented: “She was always in a rush now…. She ate all her meals with her friends. Never with the boy or his mother. She smoked cigarettes” (Otsuka 92). Meal times were hectic and people hardly ate with their families. Young girls relied heavily on their friends and through the months of internment they grew farther apart from their immediate families. Traditions that their parents had learned from grandparents were not as easily taught to the newest generations and generational intimacy waned. As women began relocating after the war they found themselves inundated with friends trying to readjusted to post-internment life. Peers’ homes were often used as stepping stones until a permanent residence could be found. The World War II internment camps had helped to create more independent women while subverting traditional Japanese relationships. The internment process started a new era for Japanese women. They suffered tremendous indignities and powerful psychological changes that would stay with them for the rest of their lives. As they fought the elements they challenged themselves to expand their knowledge and job experiences. Upon leaving the camps Japanese women faced an uncertain future (perhaps the most frightening part of their predicament) and racial tension everywhere they traveled. They experienced a greater multitude of change than any other segment of the internees. Some of these changes were for the better, most of them were for the worse. The Japanese internment camps were a dark period in our history and we can never allow a comparable condition to arise again. Works Cited “Employment Procedure Established.” Topaz Times. 23 May 1942. Utah Digital Newspapers. The University of Utah. Accessed: 26 Oct. 2009 Matsumoto, Valerie. “Japanese American Women during World War II.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1984), pp. 6-14. JSTOR. Accessed 26 Oct. 2009 Otsuka, Julie. When the Emperor was Divine. New York: Anchor Books, 2002. Print.