PowerPoint Chapter 5

advertisement

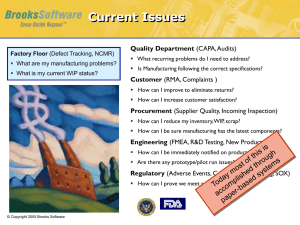

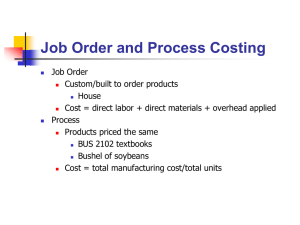

Management Accounting: A Road of Discovery Management Accounting: A Road of Discovery James T. Mackey Michael F. Thomas Presentations by: Roderick S. Barclay Texas A&M University - Commerce James T. Mackey California State University - Sacramento © 2000 South-Western College Publishing Chapter 5 How do things really work? Accumulating product costs Key Learning Objectives 1. Discuss how work traditionally has been organized and how cost accounting measures work efficiently. 2. List the source documents required for direct cost assignment. 3. Prepare a predetermined overhead rate and justify its allocation base. 4. Explain the need for equivalent units and calculate the average department cost per equivalent unit in a process costing system. 5. Describe how WIP is organized in a job costing system and calculate a job’s cost. 6. [Appendix A] distinguish between service and line departments, and justify the need for departmental PORs. PART I SCIENTIFIC MANAGEMENT AND THE ECONOMIES OF SPECIALIZATION Well Engineered Processes Identify and break down complex processes into small sets of subtasks. Design each task to be easy to learn quickly to lower the skills required. Create functionally specialized departments to reduce the variety of skills required. Cheap, low skilled workers are easily replaced and become a variable cost. Each Production Subtask Uses the Same Sequential Activities Move-wait-setup-run-quality inspection Run is the production task Move and wait are coordination activities Setup activities adjust machines for different products Quality inspections occur as needed (or desired) Management skill is needed to coordinate activities Fixed costs are need to support this system ‘Keeping busy’ reduces unit costs Multree’s Sawing Department Production Cycle — an Illustration Management Activities MOVE—Order lumber from raw materials inventory WAIT—Have lumber available when saw is ready SETUP—Order sent to Machining Department for saw setup specialist RUN—Schedule workers MOVE—Order sawed lumber to be moved to WIP storage area Operations Activities MOVE—Forklift truck moves lumber to Sawing WAIT—Lumber stacked next to saw SETUP—Specialists set up machines (saws) for the specific work needed RUN—Saw lumber MOVE—Forklift truck moves lumber to stock yard Management of Uncertainty [Coordination and Control] Dealing with low skills, poor quality materials, and unreliable machines Limits to the size of functional departments by the ‘span of management control’ How many workers can the expert supervise? Example. Suppose the expert can answer 2 questions an hour. If each worker asks one question per shift, then the expert can manage 16 workers. As variety or uncertainty increases, more questions are asked and the effective span of control for the supervisor decreases. Decreasing uncertainty and variety or increasing worker skills increases the span of control. The opposite conditions result in the opposite effect Coordination Using Slack & Buffers to Manage Uncertainty Allows room for variation Variety is the number of different tasks required Increasing variety means workers are required to know how to perform more different tasks. Example: Learning to do one task takes 10 minutes. Learning 3 tasks takes 30 minutes plus another 10 minutes learning how to coordinate each pair of tasks. 3 tasks can be combined in 3 ways for another 30 minutes. As tasks increase, learning gets more expensive. Move-Wait-Setup-Run to Make Chairs— An Illustration of Slack and Buffers 3 Tasks: Cut wood, Paint wood & Assemble the chair M-W-S 30 min Runs 2 hrs Cut wood M-W-S 30 min Run 2 hrs Paint wood M-W-S 30 min Run 2 hrs Assembly Move-wait-setup [M-W-S] takes 30 minutes on average between each run activity. Scheduling: Perfect operations [no slack] = 7.5 hours Practical operations [slack] = 9 hours More Considerations— Slack and Buffers WIP inventory buffers allow piles of extra WIP stock in front of each activity to assure components are always available. Thus workers can keep busy regardless of when components are delivered or their quality. Buffers and slack allow functional departments to operate more-or-less independently. If this is true, then maximizing the efficiency of each separate department should maximize the efficiency of the company as a whole. The Management Problem: Managing Uncertainties The uncertainty Examples Missed delivery dates, wrong materials received, wrong amounts received Machine breakdowns, inconsistent output quality Unreliable deliveries Unreliable machinery Product quality problems Bad raw materials, bad WIP, bad final products Labor problems Poorly educated, poorly motivated Fluctuating product demand Actual orders change after scheduled to be built and/or production started Solutions Extra raw materials inventory Extra machines, extra machine time, extra WIP, extra finished goods Extra raw materials, extra WIP inventory, extra finished goods inventory Simplify tasks, allow extra time for each task, hire extra workers Extra raw materials, extra WIP and finished goods inventory Management Using Cost and Profit Centers Role of accounting using this management philosophy Costing products as they flow through the production process—raw materials, work in process inventories, and finished goods (this chapter). Providing information to support decisions within functional departments (Chapter 7). Helping management control to ‘get people to do what you want them to do’. Accounting accumulates and assigns costs to departments and responsible managers. PART II COSTING SYSTEMS • TERMS DEVELOPED TO COST PRODUCTS • MEASURING THE FLOW OF COSTS • PROCESS COSTING SYSTEMS • JOB COSTING SYSTEMS Terms Developed to Cost Products GAAP requires that all manufacturing costs be applied to, or absorbed into, the products made. All nonmanufacturing costs are applied to the time period where they are consumed. Illustration of GAAP Rules Product Costs Full manufacturing costs applied to inventory accounts. All manufacturing costs ‘absorbed’ into inventory values Manufacturing functions Direct costs—Can be physically traced to individual products Direct materials Direct labor Relatively accurate assignment of costs Period Costs All other costs related to being in business Nonmanufacturing functions Indirect costs—Are necessary to make products but difficult to trace to individual products Indirect overhead costs This approach is a source of error since costs are assigned (allocated) to products using estimates through predetermined overhead rates Predetermined Overhead Rates (Volume Based) NOTE: This is the first of several slides discussing and illustrating this concept. Predetermined Overhead Rate = Indirect Overhead Cost Predicted Volume of Activity The logic: The overhead costs are incurred to support a specified level of capacity or production ‘volume’ within our relevant range. There the ‘cause and effect’ argument is to allocate overhead costs by the ‘volume of capacity’ consumed or used. Capacity is measured by many different volume related measures in practice, I.e., direct labor hours, machine hours, etc. For Example: Indirect overhead budgeted is $1,000,000 and 50,000 direct labor hours are needed to make the budgeted production. Predetermined overhead rate = $1,000,000 50,000 DLHs = $20 per DLH Thus for the chair we made earlier, the overhead assigned is based upon the 6 runtime hours. The overhead assigned is $120 (6 hours x $20). Illustration: Assigning Manufacturing Costs to Chairs Each chair is assigned three product costs: Direct materials, Direct labor, and Indirect overhead costs. Given the predetermined overhead rate is $20, assume direct materials costs $80 and the direct labor rate is $12 per hour. Costs assigned to each chair by the accounting system is: Direct materials Direct labor (6 hrs @ $12) Manufacturing overhead (6 hrs @ $20) Unit cost $ 80 72 120 $272 For finished goods, each chair is costed at $272 Illustration Continued Go back to the Move-Wait-Setup-Run flow illustration for chairs shown earlier. What do you think the work in process Inventory cost should be for a semi-finished chair that has been cut and painted buy not yet assembled? There is a lot of variation in how these costs are applied to inventories in practice. However, for GAAP purposes, any ‘full or absorption’ costing systems that apply all the manufacturing costs in a consistent logical manner is acceptable. We will examine two approaches — Process and Job Costing. Costing procedures in practice vary dramatically from company to company. Overhead can be applied based on departmental and company wide rates. The discussion here is simplified. Our presentation is designed to give you insight into the underlying concepts. PART 2 MEASURING THE FLOW OF COSTS THROUGH THE COMPANY Measuring Cost Flows As work is completed, Costs are absorbed in the cost objects (WIP inventories). The products are like a wave absorbing the costs that are transforming the product as it flows through the company. The Accounting System Is designed to assign manufacturing costs to WIP. Includes documentation and a set of accounts. Usually each functional department is a cost center. For each function, like sawing, painting, and assembly summary sets of accounts are used to accumulate coast and assign them to products. Some Commonly Used Documents Purchase orders to authorize the purchase and receipt of materials. Receiving reports to document that we have received the materials and authorize payment. Material requisitions to track the movement of materials within the company and trace materials to products. Time cards to directly trace labor costs to products. Note: Refer to Exhibit 5-8, p.153 of your text to view a flow diagram of Multree’s manufacturing process. PART 3 PROCESS COSTING SYSTEMS Process Costing Systems — Basic Concepts When each product is manufactured in the same manner, we can use process costing (homogeneity). A key concept is an equivalent unit. This means the work in two units half finished is equal to the work in one finished unit. Another concept is that the resources needed to make a product are not consumed uniformly. That is, all the materials may be added at the beginning of the work, while direct labor and overhead are applied uniformly to convert the materials to a finished product Conversion costs). Pattern of Resource Use Equivalent Units vs. Percentage of Completion Direct Labor Applied uniformly Direct Material Applied at the beginning of the process Overhead Applied using Direct Labor hours Diagram Analysis and Discussion From these drawings, when a product is half done it has consumed. Equivalent units of direct labor = Equivalent units of direct materials = Equivalent units of overhead = .5 E.U.’s 1.0 E.U.’s .5 E.U.’s A WIP unit that is half done has the same materials as one finished unit and half the direct labor and overhead as a finished unit. Steps in Process Costing Determine the number of input factors needed. Determine the equivalent units of each input used. Calculate the costs of each input consumed in production. Calculate the cost per equivalent unit of each input. Cost per E.U. of direct labor = Direct labor costs E.U.s of direct labor Using equivalent unit costs, assign the appropriate costs to the goods finished and the WIP Illustration Background Let’s develop the assignment of the costs for work done in the painting department. During the month costs are accumulated for each department. For accounting purposes we need to allocate these costs to products worked on each month. How can we use process costing to assign costs to inventories? Transferred out WIP inventories are sent to the assembly department to be finished. WIP inventories remain in the department at the end of the accounting period. Step One: Determine the number of input factors needed. The components for each chair are painted at the same time. The paint is requisitioned at the beginning of the run activity. Painting is applied at the beginning of the process by direct labor workers. Overhead costs are accumulated for the painting department and assigned to products based upon direct labor hours. Step Two: Determine the equivalent units of each input. Information must be gathered about the status of current WIP and the number of painted chair component packages (units) transferred to the assembly department during the period examined The records show 65 units were transferred this month. After examining the WIP, workers estimated that the 10 component packages in process wee 60% done. (Calculations follow on the next slide.) Step Two: (Continued) Equivalent units for materials = = = 75 Equivalent units of materials Equivalent units for direct labor & overhead (conversion costs) = = = = 71 equivalent units Step Three: Calculate the costs of each input consumed in production. All the overhead costs gathered for the month plus all the direct labor costs add up to 44,544. The costs transferred in from the sawing department plus the paint requisitioned for the month adds up to $12,600. Step Four: Calculate the cost per equivalent unit for each input. Cost per E.U. of materials = Cost per E.U. of conversion costs = Step Five: Using equivalent unit costs, assign the appropriate cost to the goods finished and WIP Costs assigned to the 10 component packages in WIP = = = $2,064 Costs assigned to the 65 packages (units) transferred out to assembly = = = $15,080 Process Costing Can Be Almost Infinitely Complex What would happen to our calculations if we started with WIP? How would we calculate the costs of spoilage and waste if we want to record it separately? How would you track costs if you use LIFO, FIFO, or Weighted Average? How difficult would this be if the costs varied due to variation in the quality of materials, labor, and breakdowns occurred? PART 4 JOB COSTING SYSTEMS Job Costing—General Process costing systems are good enough for products that consume the same resources but when products consume resources differently, job costing systems are needed. Job costs systems have documents that track costs to individual jobs not departments. Each job can be assigned a unique combination of costs. WIP Subsidiary Ledger Accounts in Job Costing Systems WIP Job 101 Direct materials Lumber Sheetrock Cabinets Appliances Other costs Direct Labor Sawing Framing Wiring Plumbing Other costs Applied O/H @$4.74 Total job cost Ending balance WIP Job 245 WIP Job 347 $ 8,000 1,500 5,000 3,250 8,500 $7,500 900 3,500 $10,500 2,100 1,250 1,725 1,475 1,350 19,200 11,850 1,000 1,400 1,200 2,500 1,125 2,175 1,750 3,000 2,891 3,816 $63,100 $0 $20,891 $24,466 An Illustration Suppose each chair (or job lot of chairs) is custom designed. Materials, painting, and assembly costs are influenced by the product design. The painting department uses job costing. Direct labor rates are still $12 per hour and the POR rate is still $20 per direct labor hour. Three Jobs were Worked on During the Period: Job 111 (20 units) = Job 122 (3 units) = Job 122 (10 units) = Beginning WIP cost is $4,000. 40 direct labor hours are used to finish the job. This job was started and finished this period. The transferred in costs from sawing were $2,200 each. No additional materials were added, but it took 120 labor hours to finish the job. This job took 10 units from sawing costed at $200 each. It was not finished and only 10 hours of work had been applied this month. Calculation of Costs Assigned to Each Job Job 111 (20 units) Beginning work in process + Direct labor costs (40 x $12) + Overhead applies (40 x $20) Total Costs $4,000 480 800 $5,280 Cost per unit = ($5,280/20) = $264 Job 121 (3 units) Transferred in direct materials ($2,200 x 3) + Direct labor (120 x $12) + Overhead (120 x $20) Total Costs Cost per unit = $10,440/3 = $3,480 $ 6,600 1,440 2,400 $10,440 Calculations: (Continued) Job 122 (10 units) — Ending WIP Transferred in direct materials + Direct labor + Overhead Total costs Ending Work in Process inventory = $2,820