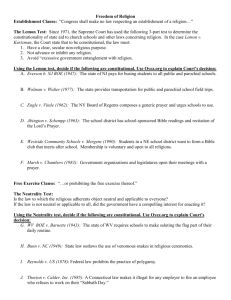

Establishment Controversies

advertisement

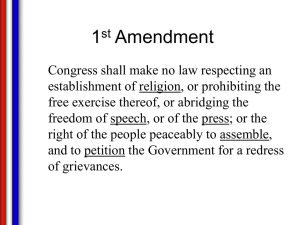

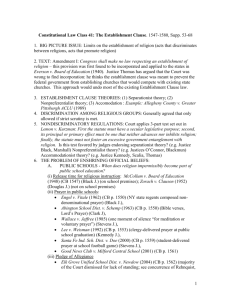

The Bill of Rights Institute Memphis, TN October 28, 2010 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University King George III Head of the Church of England Ruler of the American Colonies • • • The First Amendment states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion” What does this mean? There are two broad interpretations: Separationist—strict division between government and religion; Accommodationist—allows intermingling between government and religion. The justices of U.S. Supreme Court have generally fallen into one camp or the other. Accordingly, Supreme Court precedent in this area is mixed. • • • The Court upheld a state’s reimbursement to parents of parochial school children for the cost of busing their kids to religious schools. The Court reasoned that the taxpayer funds were permissible because they went to the children/parents and not the religious schools. But . . . The Court also said, “In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between Church and State.’” In a majority opinion by Justice Hugo Black, the Court went on to say: “The ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the federal government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or nonattendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa.” New York composed and required a prayer to begin the school day: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our Country.” Justice Black held: “Petitioners argue [that] the State's use of the Regents' prayer in its public school system breaches the constitutional wall of separation between Church and State. We agree since we think that the constitutional prohibition against laws respecting an establishment of religion must at least mean that in this country it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by government.” Members of the group that challenged New York’s compulsory prayer law. Pennsylvania law declared that at least 10 verses from the Bible shall be read without comment at the beginning of each public school on each school day. At Abington High, the verses were read over the loud speaker and were then followed by a recitation of the Lord's prayer, during which students stood and repeated the prayer in unison. Students who did not want to participate could leave the room. The Court asked what the purpose and primary effect of the policy were and found it unconstitutional. The justices reasoned that the state passed the law to promote religion and the effect was to coerce students to participate in religion. A majority of Americans have never approved of the school prayer and bible reading decisions. Today only about 1/3 agree. 1) 2) 3) At issue was a state law that reimbursed religious schools for non-religious textbooks and salaries for non-religious teachers. The Court articulated what became known as the “Lemon Test” – a judicial standard based on past establishment decisions. A policy must pass all three parts to be valid: Does program at issue have a secular legislative PURPOSE? Is the primary EFFECT to inhibit or advance religion? Does the legislation foster an EXECESSIVE GOVERNMENT ENTAGLEMENT with religion? This test became divisive in subsequent cases and though it has been slightly modified, it is essentially in tact as good law today. Applying the three-part framework, Chief Justice Burger struck down the state law based on the third prong. He reasoned that unlike textbooks, it was easy for teachers to inject religion into their teaching. Though the aid only went to teachers of "secular" subjects, they were employed by and subject to supervision and disciplinary action by the church. Because most lay teachers were of the Catholic faith, there was potential for public funds to be used for religious instruction. Because of this potential danger, the state would have to continually monitor the school to make sure the money was being distributed correctly. This would be excessive involvement. Marian Ward, a 17-year-old student, says a prayer over the PA system before a Santa Fe High School football game. In Marsh v. Chambers (1983) the Court upheld the practice of opening a state legislative session with a prayer, relying on the longstanding practice of Congress and of the founders. But is a state-approved, clergy-led prayer at a public school graduation ceremony constitutional? Justice Kennedy initially voted that it was, switched his vote, and finally struck down the policy for a 5-4 majority. Instead of applying the Lemon Test, Kennedy applied what Justice Scalia mockingly called the “psychocoercion test” Kennedy said that “subtle coercive pressures exist and the student had no real alternative which would have allowed her to avoid the fact or appearance of participation.” Similarly, in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000) the Court struck down (6-3) a student-led prayer at a High School football game. For a 5-4 majority, Chief Justice Rehnquist upheld a government program providing tuition vouchers for Cleveland schoolchildren to attend private (including religious) schools. He applied the Lemon test and reasoned that because the vouchers went to parents and they made a “private choice” the program was constitutional. “No reasonable observer would think a neutral program of private choice, where state aid reaches religious schools solely as a result of the numerous independent decisions of private individuals, carries with it the imprimatur of government endorsement.” 1) 2) The dissenters (Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) emphasized two key points: Religious use of public funds will increase the risk of religious strife and religiously-based social conflict—the very thing the Establishment Clause was put in place to avoid Public funds allow religious schools to divert money to religious instruction that would have been used for secular purposes: scholarships, busing, textbooks, etc. The Pledge of Allegiance has included the phrase “under God” since 1954. California requires public elementary school teachers to lead students in the Pledge. Newdow, an atheist, challenged the Pledge that his daughter was required to recite. The Court ducked the issue by holding that Newdow, as a divorced father who did not have legal custody of his daughter, did not have standing to bring the suit. In his opinion for the Court, liberal Justice John Paul Stevens added: “[The Pledge’s] recitation is a patriotic exercise designed to foster national unity and pride in those principles.” Still, Rehnquist, O’Connor, and Thomas went to great lengths in separate opinions to explain why the Pledge was constitutional. It may only be a matter of time before the Court decided the issue on the merits. 1) 2) In two cases, the Court held 5-4 that: Two large, framed copies of the Ten Commandments could not be displayed in a courthouse building because they were placed there relatively recently and were displayed by themselves – McCreary County v. ACLU (2005) But, a six-foot monument displaying the Ten Commandments could be placed on public grounds because it was longstanding and was placed with other historical monuments – Van Orden v. Perry (2005). In each case Justice Stephen Breyer was in the majority. He explained his reasoning in a concurring opinion in Van Orden: “As far as I can tell, 40 years passed in which the presence of this monument, legally speaking, went unchallenged (until the single legal objection raised by petitioner). And I am not aware of any evidence suggesting that this was due to a climate of intimidation. Hence, those 40 years suggest more strongly than can any set of formulaic tests that few individuals, whatever their system of beliefs, are likely to have understood the monument as amounting, in any significantly detrimental way, to a government effort to favor a particular religious sect, primarily to promote religion over nonreligion, to "engage in" any "religious practic[e]," to "compel" any "religious practic[e]," or to "work deterrence" of any "religious belief.“ Those 40 years suggest that the public visiting the capitol grounds has considered the religious aspect of the tablets' message as part of what is a broader moral and historical message reflective of a cultural heritage.” In general, the liberals are separationist and the conservatives are accommodationist. While the Lemon test is still good law, there are other tests for specific areas of Establishment jurisprudence such as the “coercion” test used in Weisman. What will the recent turnover on the Court mean for the future of the Establishment Clause? Will the Lemon test survive?