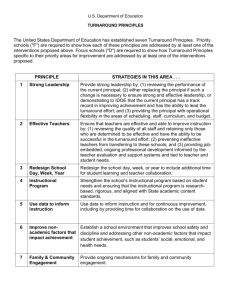

spec item1 emergingpractices

advertisement