2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

6

CHAPTER 6

SUICIDALITY AND SELF-INFLICTED INJURY

INTRODUCTION

Nationally, youth suicide rates tripled in the second half of the 20 th century (6a). In 2003, suicide was the third

leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 24 in Massachusetts and in the United States as a

whole (6b). One risk factor for suicide is untreated depression, yet only a small percentage of Americans who

suffer from depression are accurately diagnosed and treated (6c). Other risk factors include bullying, other

physical or sexual abuse, interpersonal losses, and school or work problems (6d).

National Health Objectives for the Year 2010 include reducing the incidence of suicide attempts and completed

suicides among adolescents. The 2005 MYRBS asked students several questions about suicidal thoughts and

behaviors during the previous year, including questions concerning (1) feeling sad or hopeless, (2) serious

considerations of suicide, (3) plans to commit suicide, (4) actual suicide attempts, and (5) medical treatment

required as the result of a suicide attempt. In addition, the MYRBS asked about intentional self-injury including

cutting, burning, or bruising.

KEY FINDINGS FROM THE 2005 MYRBS

Significantly fewer students in 2005 than in previous years seriously considered suicide (13%), made a

suicide plan (12%), or actually attempted suicide in the past year (6%). Two percent (2%) of all students

received medical attention for a suicide attempt.

Slightly less than one-fifth of all students (19%) reported hurting themselves on purpose.

Female students were more likely than male students to report suicidal thinking, feeling sad or hopeless

for two weeks or more, or to have injured themselves on purpose. Small gender differences in actual

suicide attempts were not statistically significant.

Students receiving special education services, homeless students, sexual minority youth, students who

engaged in binge drinking or illegal drug use, and students who have experienced violence were more

likely than their peers to report a suicide attempt.

RESULTS

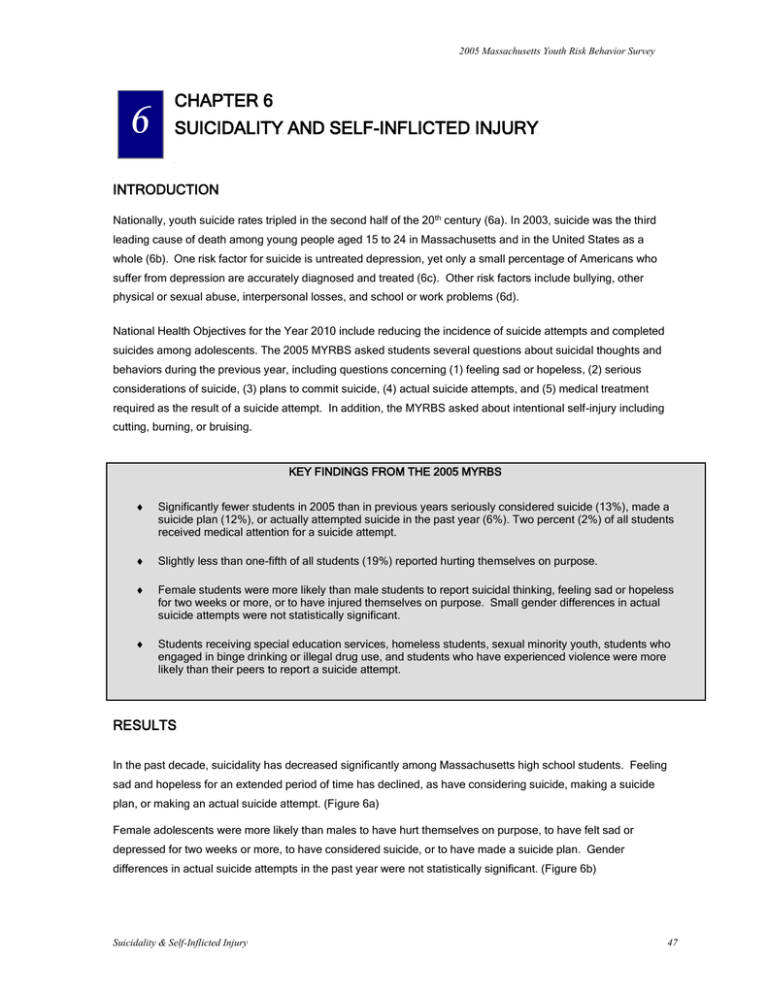

In the past decade, suicidality has decreased significantly among Massachusetts high school students. Feeling

sad and hopeless for an extended period of time has declined, as have considering suicide, making a suicide

plan, or making an actual suicide attempt. (Figure 6a)

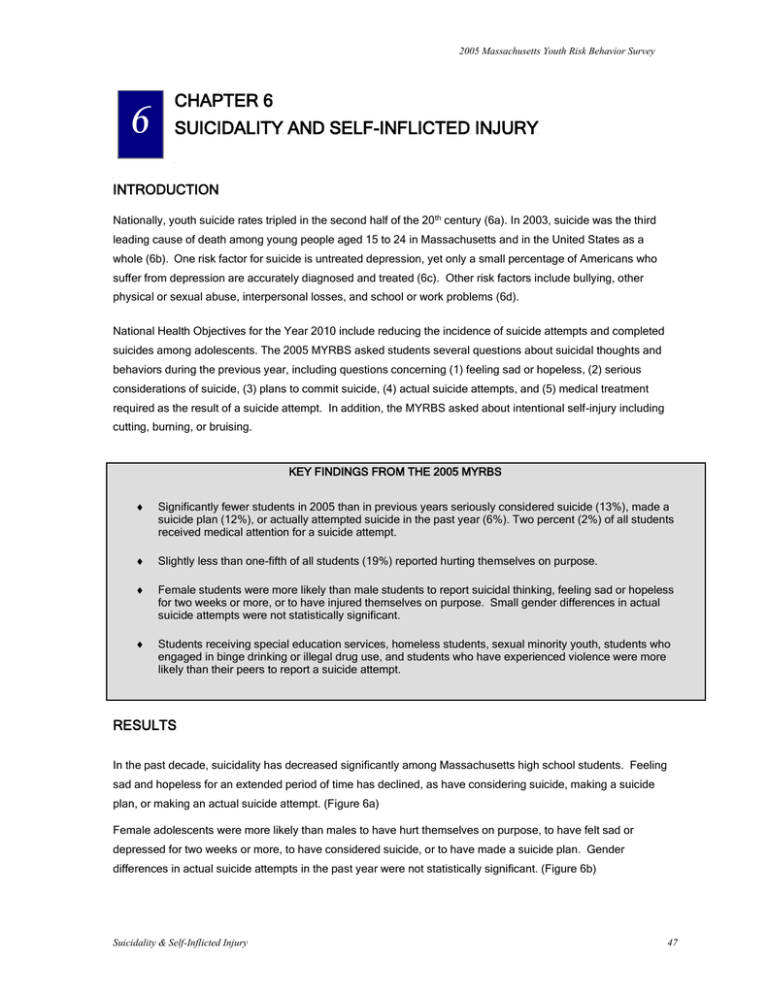

Female adolescents were more likely than males to have hurt themselves on purpose, to have felt sad or

depressed for two weeks or more, to have considered suicide, or to have made a suicide plan. Gender

differences in actual suicide attempts in the past year were not statistically significant. (Figure 6b)

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

47

2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Figure 6a: Suicidal Thinking and Behavior Among Massachusetts High School Students,

1995 - 2005

1995

30.4

28.8

28.0

26.7

35

1997

25.8

23.5

21.2

20.1

12.7

16.3

20

2001

15

2003

2005

10.4

9.5

8.3

9.6

8.4

6.4

25

1999

18.8

19.2

16.6

15.2

12.5

11.7

30

3.6

3.7

4.1

3.5

2.8

2.4

10

5

0

Felt sad or hopeless Seriously considered Made a suicide plan,

for 2 weeks or more, suicide, past year

past year (*b)

past year (*a)

(*b)

Attempted suicide,

past year (*c)

Suicide attempt with

injury, past year (*a)

(*a) Statistically significant decline from 1999 to 2005, p < .05. (*b) Statistically significant decline from 2001 to 2005, p < .05. (*c)

Statistically significant decline from 2003 to 2005, p. < .05.

Figure 6b. Suicidal Thinking and Behavior Among Massachusetts

High School Students by Gender, 2005

Female

33.4

40

35

Male

2.5

5

2.4

5.6

20.2

10

7.2

9.8

13.5

10.2

15

15.2

20

14.2

25

22.8

30

0

Hurt self on

Felt sad or

purpose, past hopeless for 2

year (*)

weeks or more,

past year (*)

Seriously

considered

suicide, past

year (*)

Made a suicide

plan, past year

(*)

Attempted

suicide, past

year

Suicide attempt

with injury, past

year

(*) Statistically significant gender differences, p < .05

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

48

2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

26.8

28.2

26.0

25.1

Figure 6c. Suicidal Thinking and Behavior Among Massachusetts High School

Students by Grade, 2005

10th Grade

11th Grade

12th Grade

Seriously

considered

suicide, past

year

Made a suicide

plan, past year

6.9

6.5

5.3

6.3

10

5

2.5

2.3

1.5

3.1

15

11.1

11.7

10.4

13.2

20

14.0

12.1

11.1

12.8

16.5

14.0

25

9th Grade

21.4

20.8

30

0

Hurt self on

Felt sad or

purpose, past hopeless for 2

year

weeks or more,

past year

Attempted

suicide, past

year

Suicide attempt

with injury, past

year

Black

Hispanic

27

Asian

5

14.8

1.9

3.6

4.8

5.8

5.9

10

9.2

15

Other/Mixed

12.9

12.4

9.7

12.2

15.5

20

11.2

10.6

12.7

13.4

20.5

25

5.2

7.7

30

25.7

25.6

35

29.8

35.4

40

36.9

Figure 6d. Suicidal Thinking and Behavior Among Massachusetts High School

Students by Race/Ethnicity, 2005

White

0

Felt sad or hopeless

Seriously

for 2 weeks or more, considered suicide,

past year (*)

past year (*)

Made a suicide

plan, past year

Attempted suicide, Suicide attempt with

past year (*)

injury, past year (*)

(*) Statistically significant racial/ethnic differences, p < .05.

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

49

2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Female adolescents were more likely than males to have hurt themselves on purpose, to have felt sad or

depressed for two weeks or more, to have considered suicide, or to have made a suicide plan. Gender

differences in actual suicide attempts in the past year were not statistically significant. (Figure 6b)

Nearly one in five students (19%) indicated that they had hurt themselves on purpose at least once in the past

year, for example by cutting, burning, or bruising themselves. This represents a slight, non-significant, increase

over the 18% reported in 2003, the first year the question was included on the survey.

ADDITIONAL GROUP DIFFERENCES IN SUICIDALITY

Community differences in suicidality varied by question asked. Rural youth were more likely than their urban or

suburban counterparts to indicate that they had cut, burned or hurt themselves on purpose in the past year (23%

vs. 16% and 19%). On the other hand, rural adolescents were less likely than urban and suburban peers to

report that they had made a past-year suicide attempt that resulted in an injury (1.3% vs. 3.3% and 2.2%). Other

community differences were not significant.

Special education students were more likely than general education students to report considering suicide (17%

vs. 12%), making a suicide plan (15% vs. 11%), and making a suicide attempt resulting in injury (5% vs. 2%).

Sexual minority adolescents – those who self-identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual or who reported any samesex sexual contact – had suicidality rates nearly double those of their peers. For example, they were more likely

to have hurt themselves on purpose (44% vs. 17%), to have seriously considered suicide (34% vs. 11%), and to

have made a suicide attempt in the past year (21% vs. 5%).

Immigrant and US-born adolescents were similar in terms of suicidal thinking and behavior.

Every measure of suicidality was over twice as high among homeless youth as among adolescents living at home

with their families. For example, homeless students were significantly more likely than their peers to have hurt

themselves on purpose (38% vs. 17%), to have seriously considered suicide (28% vs. 12%), and to have made a

suicide attempt in the past year (19% vs. 6%).

RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR SUICIDALITY

As has been found in numerous other studies, substance abuse was significantly associated with suidicality. For

example, past-year suicide attempts were significantly more frequent among youth who reported binge drinking

than among those who did not (11% vs. 5%) and among those who had ever used cocaine than among those

who had not (24% vs. 5%).

Suicidal thinking and behavior were more common among youth who had been victimized. For example, pastyear suicide attempts were significantly more common among students who had been bullied at school than

among their peers (12% vs. 5%) and among adolescents who had experienced dating violence than among their

peers (23% vs. 5%).

Suicide attempts were reported significantly more frequently by overweight adolescents than by their peers (9%

vs. 6%).

Perceived social support appeared to exert a protective effect against suicidality. Suicide attempts were less

common among students who believed there was a teacher or other school staff member they could talk to if they

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

50

2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

had a problem (5% vs. 11%) and among youth who reported that they could talk with family adults about things

that were important to them (5% vs. 13%).

Students who were earning passing grades – A’s, B’s, and C’s – were significantly less likely to have made a

suicide attempt in the past year than those who were not (5% vs. 12%)

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Massachusetts can be encouraged by the significant declines in suicidal thinking and behavior among youth over

the past decade. Even so, over one-eighth of Massachusetts high school students report having felt so much

distress and despair over the past year that they seriously consider killing themselves; many actually make

suicide attempts. All schools and communities need to address the seriousness of adolescent suicide. The

National Strategy for Suicide Prevention includes an objective to increase the proportion of school districts and

private school associations with evidence-based programs designed to address serious childhood distress and

prevent suicide (6e).

Researchers have begun to identify successful school-based approaches to youth suicide prevention (6f, 6g).

Schools can address the problem of youth suicide directly using effective prevention programs that help students

learn to recognize and manage the feelings of stress and depression that may lead to suicidal thinking and

behavior. However, research has shown that suicidal adolescents are not likely to seek help on their own (6e).

Therefore, it is important that school staff be trained to recognize early signs of depression and serious emotional

disturbances among young people (particularly among high-risk subgroups such as sexual minority youth, and

students who have been victims of violence), and be able to direct at-risk students to appropriate mental health

services.

One early sign of depression and suicidality may be self-inflicted injury. Students who reported hurting

themselves on purpose (for example, by cutting, burning, or bruising themselves) were far more likely than their

peers to have felt sad or hopeless, or to have considered, planned, or attempted suicide.

Many influences may contribute to an adolescent’s intention to commit suicide, but some promising protective

factors have also been identified. Recent research from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health

found suicidality to be significantly lower among high school students who felt emotionally connected to their

parents and/or family (6h). The 2005 MYRBS results support that view. Massachusetts students who felt there

was a parent or other adult in their family they could talk to about things that were important were less likely than

their peers to have attempted suicide. Conversely, adolescents who were threatened, bullied, or intimidated at

school or who felt so unsafe that they sometimes skipped school altogether had far higher rates than their peers

of suicidal thinking and behavior. Schools should work to foster an environment in which all students feel safe,

accepted, and supported, and where all have the opportunity for social recognition and for responsible

involvement in school activities.

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

51

2005 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey

CHAPTER 6: REFERENCES

6a. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1990). Prevention ‘89/90: Federal programs and progress.

Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

6b. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. (2006).

WISQUARS leading causes of death reports. Retrieved November 5,2006 from

http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus.html

6c. American Psychiatric Association (1994). DSM-IV: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

6d. Gould, M., Greenberg, T., Velting, D., & Shaffer, D. (2006) Youth suicide: A review. The Prevention

Researcher, 13, 3-7.

6e. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service (2001). National strategy for suicide

prevention: goals and objectives for action. Rockville,MD: author.

6f. Aseltine, R.H., & DeMartino, R. (2004). An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program.

American Journal of Public Health, 94, 446-451.

6g. Kalafat, J. (2006). Youth suicide prevention programs. The Prevention Researcher, 13, 12-15.

6h. Resnick, M. et al (1999). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study

on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 823-832.

Suicidality & Self-Inflicted Injury

52