The Calvinist – Arminian Debate Stephen M. Clinton 1977

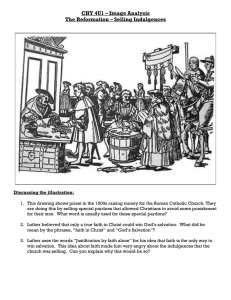

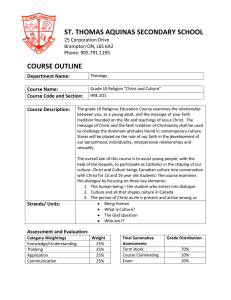

advertisement