Pitfalls [and Possibilities] in the Use of Maps to Visualize Earth Data and Understand Earth Processes

advertisement

![Pitfalls [and Possibilities] in the Use of Maps to Visualize Earth Data and Understand Earth Processes](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015134490_1-90e7c3fb6420d106aaeab9c5dc28ed99-768x994.png)

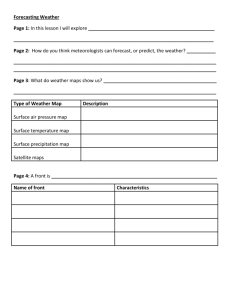

Pitfalls [and Possibilities] in the Use of Maps to Visualize Earth Data and Understand Earth Processes Kim Kastens Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University Presented at workshop on Use of Visualization in Geosciences Carleton College, February 27, 2004 Pitfalls: Preview • Many students are weak in projective spatial skills: bad news for map projections • Students’ prior map skills training may have lacked any connection with the real world • When maps and profiles are combined to explore a data volume, likelihood of nonpenetrative errors • Clearly articulating and modelling an approach to mapbased data exploration that works for professionals may be insufficient for novices • Understanding is not the same as believing and acting upon. Pitfall #1 Projective spatial skill includes the ability to anticipate the shape of a projection (or shadow) cast by an object held up to a light. (from Downs & Liben, 1991) Good answers show understanding of variation as a function of the angle of presentation of shape relative to the light and screen. Good answers show understanding of variation as a function of thickness of the shape. Mistaken answers include: • upside down “shadows” • incomplete “shadows” • concave “shadows” of convex objects • asymmetrical “shadows” of symmetrical objects • inconsistent treatment of thickness of object (from Downs & Liben, 1991) This projective spatial skill is important in teaching about maps because map projections are often illustrated by having students envision a light inside the globe that projects shapes from the surface of the globe onto a sheet of paper held tangent to the Earth’s surface. (http://www.cfr.washington.edu/research.urbaneco/GIS_Tutorial/UEGIS-tutorial-notes.htm) Data from Downs & Liben (1991) Degrees of rotation of object from vertical Mean number of correct answers selected (out of 6) 30° 60° 90° (flat) Male 5.4 5.2 5.1 Female 4.9 4.9 3.3 Male 1.1 1.3 4.9 Female 0.7 0.9 2.8 Thin Forms Thick Forms Many college students do very poorly on Downs & Liben’s shadow projection test. How well do you suppose these students will understand standard explanations of map projections? What can we do to help them? [Not to mention other, more obscure, spatial representations used in Geosciences, which rely heavily on projective spatial skills.] from: Hobbs, Bruce E., Winthrop D. Means, and Paul F. Williams (1976) An Outline of Structural Geology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pitfall #2 Frontispiece from Geography for Life: The National Geography Standards What is odd about this picture? Frontispiece from Geography for Life: The National Geography Standards It doesn’t show a school or a school activity! That’s because the crucial and complex skill of translating between the real world and the representation (the map) is usually not taught in school. The City Park is between which streets? A and B Streets B and C Streets A and C Streets How many stores are on the map? 0 1 2 3 4 5 For many elementary school map skills activities there is no actual represented space. Or even if the represented space does exist, the questions can be answered entirely in the frame of reference of the map, without thinking about the represented space. It’s like learning to read musical notation without connecting it to the heard sounds. ? equals SK A T PLACE ("reality") CHILD REPRESENTATION (map) (diagram after Liben, 1997) Dependent Variable (after Liben, 1997) Many elementary school map skills curriculum materials involve tasks that can be solved entirely in the frame of reference of the map, without ever thinking about the represented space (the real world). Vi deo Sta rt bu tton Map Key bu tton : Click for expl anation of map symb ols Symbo l fo r wate r fo unta in ha s be en ad ded to th e ma p. Wa ter fountain i n vide o Tu rn Righ t arro w Move Forward Arro w Symbo ls that can b e dra gged an d dro pped on to m ap Tu rn Le ft a rrow Retu rn to mai n me nu b utto n Red dot shows wh ere you are "stan ding ." Arro w shows wh ich way you a re " l ooking." Bla ck bal l ma rks wh ere an incorrect l oca tion was clicked . Hint Button: bring s ba ck the red dot and arrow te mpora rily. Red dot and arro w are o nly visi ble wh en you first sta rt Are We There Yet?, or if you click the "Hin t" bu tton . Comp ass Rose Gold sta r ma rks where ch ild clicked th e correct lo cation. Red line Comp ass: tra ces Sho ws th e rou te th e di rection fo llowed . to wa rds whi ch you are l ooking. Destination Pitfall #3 Many important aspects of the Earth system are inherently threedimensional, not flat like a map nor even a draped surface like the Earth’s surface….. ….. for example the ocean and its spatial distribution of salinity and temperature. So we combine maps with profiles/sections to allow students to explore a threedimensional data volume to “discover” 3-D structure and infer flows and process. It looks to me, from watching students try the ocean salinity exercise, that many are making “nonpenetrative errors” in the sense of Kali & Orion (1996): In ocean salinity exploration students can draw any N-S or E-W profile they want or maps at any water depth …. …. But they can only see one map or profile at a time. How to help learners grasp internal structure of 3-D volume? Pitfall #4 (from Mayer, 2002, based on software by W. Prothero) First Training Approach: Look at sketches of possible geological features: “Pictorial Training” (after Mayer et al, 2002) Second training approach: “Strategic Scaffolding” (after Mayer et al, 2002) Correct answers out of 5: Control (no aids) M=2.36 SD=1.52 M=3.25 SD=1.41 M=2.90 SD=1.78 Both aids M=3.39 SD=1.41 Analyzing and clearly articulating the strategies used by experts….. …. Isn’t necessarily going to be the strategy that is most effective for novices. What happens when we try to communicate outside our cozy circle of geoscientists and geoscience students? What geologists are trained to think about. Pitfall #5 What society wants to know about Forecast maps combine two challenging skills or understandings: • spatial thinking • probability How well does the intended audience of decision-makers and policy-makers understand such maps? (from International Research Institute for Climate Prediction: http://iri.columbia.edu/forecast/net_asmt) “Suppose that you were given this forecast map in January 2003. Based on this map, how would you answer the following question: ‘Which area will receive a greater amount of total precipitation for this forecast period, Southern California or Washington State?’ “ (from International Research Institute for Climate Prediction: http://iri.columbia.edu/forecast/net_asmt) Participants: 47 students in the Masters program in Environmental Science and Policy, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University (from Ishikawa, Barnston, Kastens, Louchouarn and Ropelewski , in prep) Forecast Subsequently Observed (from International Research Institute for Climate Prediction: http://iri.columbia.edu/forecast/net_asmt) “… how would you characterize the correspondence between the forecast and the observation?” (from Ishikawa, Barnston, Kastens, Louchouarn and Ropelewski , in prep) “… how would you characterize the correspondence between the forecast and the observation?” “… would you recommend that such forecasts be used to make decisions about what crops to plant?” (from Ishikawa, Barnston, Kastens, Louchouarn and Ropelewski , in prep) Understanding data (from map or otherwise)…. ….is different from believing data…. … is different from acting upon data. (from Ishikawa, Barnston, Kastens, Louchouarn and Ropelewski , in prep) Pitfalls: Review • Many students are weak in projective spatial skills • Students’ early map skills training often lacks any connection with the real world • When maps and profiles are combined to explore a data volume, likelihood of nonpenetrative errors • Clearly articulating and modelling an approach to mapbased data exploration that works for professionals may be insufficient for novices • Understanding is not the same as believing and acting upon.