et al.Catherine E. Snow,

for Learning About Science Academic Language

and the Challenge of ReadingDOI:

10.1126/science.1182597 , 450 (2010);

328Science

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only.

. clicking herecolleagues, clients,

or customers by , you can order high-quality copies for yourIf you wish

to distribute this article to others

. herefollowing the guidelines can be obtained

byPermission to republish or repurpose articles or portions of articles

including high-resolution figures, can be found

in the onlineUpdated information and services,

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/328/5977/450 version of this

article at:

found at: can berelated to this articleA list of selected additional

articles on the Science Web sites

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/328/5977/450#related-conten

t

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/328/5977/450

#otherarticles , 1 of which can be accessed for free: cites

9 articlesThis article

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/328/5977/450#

otherarticles 1 articles hosted by HighWire Press; see:

cited byThis article has been

on May 13, 2010 www.sciencemag.orgDownloaded from

(this information is current as of May

13, 2010 ): The following resources related to this article are available online

at www.sciencemag.org

:

subject collectionsThis article appears in the

following

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/collection/educ

ation Education

CopyrightAmerican Association for the Advancement of Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW,

Washington, DC 20005. (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published weekly,

except the last week in December, by theScienceregistered trademark of AAAS. is aScience2010

by the American Association for the Advancement of Science; all rights reserved. The title

S

c

i

e

n

c

e

,

L

a

n

g

u

a

g

e

,

a

n

d

L

it

e

r

a

c

y

their l earners ’ st r u g g l e s t o c o m e t o t e

r m s w i t h unfamiliar l anguage, discourse

patterns, and the often f ormidable conventions

of science ( 27 ).

References1. P. Fensham, Science Education

Policy-Mak ing: Eleven Emerging Issues [Com

missioned by United Nations Educational, Scienti fic,

and Cultura l Organization (UNESCO) Section for

Science, Technical, and Vocational Education; Paris;

2008] .2. S . P . N o r r i s , L . M . P h i l l i p s ,

Sci. Ed uc. 87 ,224 (2003).3. L. D. Yore, G. L.

Bisanz, B. M. Hand, In t. J. Sci . Edu c. 25 , 689

(2003).4. B. M. Hand, V. Prain , L. D. Yore, in Writi ng

as a Learning Tool: Integrating Theory and Practice ,

P. Tynjälä, L. Mason, K. Lonka, Eds. (Kluwer, Dordrec

ht, Netherla nds, 2001), pp. 105 –129.5. L . D . Y o r

e , D . F . T r e a g u s t , Int. J. S ci. E du c. 28

,291 (2006).6. H. Alidou et al ., Optimizin g Learning

and E du cation in Africa—the L anguag e Factor: A Stock

Tak in g Re search on Mother Tongue and Bilingual

Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (U N ESCO In s ti tu t e f

o r E d u c a ti o n , Lib r e vi ll e, G a b on , 2 00 6) .7. N.

R. Romanc e, M. R. Vitale, J. Res. Sci. Teach. 29 ,

545 (19 92).8. N. R. Romanc e, M. R. Vitale, in Linking

Sci ence and Literacy in the K – 8 Classroom , R.

Douglas,

PERSPECTIVE

M. P. Klentschy, K. Worth, W. Binder , Eds. [National

Scienc e Teacher s Association (NSTA) Press,

Arlington, VA, 2006] , pp. 391 – 405.9. N. R. Romance,

M. R. Vit ale, NSF/IERI Science IDEAS Project (Techn

ical Report 0228353- 0014, Florida Atlanti c Univers ity,

Boca Raton, FL, 2008).10. G. Cervetti, P. Pearson, M.

Bravo , J. Barber, in Linking Sci ence and Literacy in the

K– 8 Classroom , R. Douglas, M. Klentschy, K. Worth,

Eds. (NSTA Press, Arlington, VA, 2006) , pp. 221 –

224.11. O. M. Amaral, L. Garrison, M. Klent schy, Biling.

Res. J. 26 , 213 (2002).

12. M. Revak, P. Kuerbis, pap er presented at the

Inter national Meeti ng of the Association for Science

Te acher E du cation, S t. Lou i s, MO, 9 to 12 J

anuary 200 8.13. B. Hand, Ed., Science Inquiry,

Argument and Language: A Case for the Science

Writing Heuristic (Sense Publis hers, Rotte rdam, Neth

erlands, 2007).14. M. Gunel, B. Hand, V. Prain, Int. J.

Sci. Math. Educ. 5 , 615 (2007).

15. M. A. McDermo tt, B. Hand, paper presente d at

the Inter national Meeti ng of the Association for

Science Teacher Education , St. Louis, MO, 9 to 12

January 2008.16. M. Setati, J. Adler, Y. Reed, A.

Bapoo , Lang. Edu c. 16 , 128 (2002).17. Depar tment

of Education , National Education Quality Initiative and

Edu cation, Science and Skills Developm ent

Academic Language and

the Challenge of Reading

for Learning About Science

Catherine E. Snow

L

Grade 6 Systemic Evaluation (Department of Edu

cation, Pretoria , South Africa, 2005) .18. V. Rodse th,

Bilingualism and Multi lingualism in Education (Centre

for Continuing Development, Johannes burg, 1995).19.

C. Ballenger, Lang. Edu c. 11 , 1 (1997 ). 20. P .

W e b b , D . T r e a g u s t , Res. Sci. Educ . 36

,381

(200 6). 21. M. G. Villanueva, P. Webb, Afr. J. Res.

Math. Sci. Technol.Educ. 12 , 5 (2008). 22. P. Webb, Y.

Willia ms, L. Meiring, Afr. J. Res. Mat h. Sci.Technol.

Edu c. 12 , 4 (2008). 23. P. Webb, Int. J. Enviro n. Sci.

Educ. 4 , 313 (20 09). 24. C. R. Nesbit, T. Y. Hargrove,

L. Harrelson, B. Maxey,Implementing Science

Notebooks in the Primary Grades: Sc ience A ctivities J

ournal (Heldref, Washington, DC, 2003).25. D. August,

T. Shanah an, Eds., Developi ng Literac y in

Second-Lan guage Learners: Report of the National

Literacy Panel on Language-Mi nority Children and You

th (Lawrence Erlb aum, Mahwah, NJ, 2006) .26. J.

Cummins , Appl. Linguist. 2 , 132 (1981). 27. D. Hodson

, Teaching and Learni ng About Science:Language,

Theories, Methods, History, Traditions and Values

(Sense Publishers, Rotte rdam, Netherland s, 2009).

10.1126/science.1 182596

is no single variety of educated American

English. Academic language features

vary as a function of discipline, topic, and

mode (written versus oral, for example),

but there are certain common

characteristics that distinguish highly

academic from less academic or more

conversational language and that make

academic language— even well-wri tten,

careful ly c onstructed, and professionally

edited academic language—difficult to

comprehend and even harder to produce

( 8 ).

arts (mostly narratives) suggests that the

comprehension of “academic language”

may be one source of the challenge. So

what is academic language?

A

iteracy scholars and s econdary teachers

alike are puzzled by the frequency w ith which

s tudent s who read words accuratelyand

fluently have trouble comprehending text (1,

2). Such students have m astered what was

traditionally considered the m ajor obstacle t o

reading success: the depth and complexity of

the English spelling system. But many middleand high-school students are less able to

convert their word-reading skills into

comprehension w hen confronted with texts in

s cience (or m ath or social studies) than they

are when confront ed with texts of fiction or

discursi ve essays . The greater diff iculty of

science, math, and social studies texts than of

texts encountered in English language

Harvard Graduate School of Educatio n, Harvard

University, Cambridge, MA.

c

a

d

e

m

i

c

l

a

n

g

u

a

g

e

i

s

o

n

e

o

f

t

h

e

t

e

r

o

f

a

c

a

d

e

m

i

c

l

a

n

g

u

a

g

e

a

r

e

u

s

i

n

g

a

h

i

g

h

d

e

n

s

i

t

y

o

f

a

v

o

i

d

i

n

g

e

n

s

u

r

i

n

g

r

e

d

u

n

d

a

n

c

y

;

p

r

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

o

f

gDownloaded from

i

n

c

f

o

o

n

r

c 2010 VOL 328 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

m 450

23 APRIL

i

a

s

t

e

i

n

o

e

n

s

s

b

,

e

a

a

r

c

i

h

n

i

g

e

v

w

e

o

d

r

d

b

s

y

,

SPECIAL SECTION

From http://www.lowrider.com/forums/10-Under-the-Hood/topics/183-HP-vs-torque/posts (spelling as in the original

posting)

Often times guys get caught up in the hype of having a big HP motor in their

lolo. I frequently get asked whats the best way to get big numbers out of

their small block. The answer is not HP, but torque. "You sell HP, you feel

torque" as the old saying goes. Most of us are running 155/80/13 tires on

our lolo's. Even if you had big HP numbers, you will *never* get that power

to the ground, at least off the line. I have a 64 Impala SS 409, that i built

the motor in. While it is a completely restored original (I drive it rolling

on 14" 72 spoke cross laced Zeniths), the motor internals are not. It now

displaces 420 CI, with forged pistons and blalanced rotating assembly. The

intake, carb and exhaust had to remain OEM for originality's sake, and that

greatly reduces the motors potential. Anyway, even with the original 2 speed

powerglide, it spins those tires with alarming ease, up to 50 miles per hour!

In my 62, I built a nice 383 out of an 86 Corvette. I built it for good bottom

end pull, since it is a lowrider with 8 batteries. And since it rides on

the obligitory 13's, torque is what that car needs. It pulls like an ox right

from idle, all the way up to its modest 5500 redline. But I never take it

that high, as all the best power is from 1100 to 2700 RPM.

So when considering an engine upgrade, look for modifications that improve

torque. That is what your lolo needs!

Posted by Jason Dave, Sept 2009

Jason you are right on bro. I have always found an increase in torque

placement has not only provided better top end performance but also improved

gas mileage in this expensive gas times.

Posted by Gabriel Salazar, Nov 2009

From http://www.tutorvista.com/content/physics/physics-iii/rigid-body/torque.php

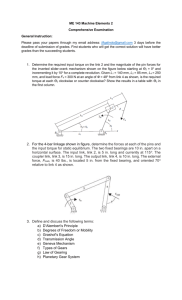

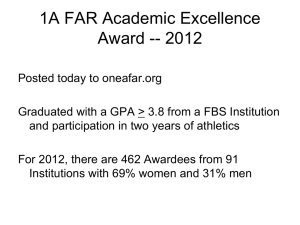

Fig. 1. Examples of nonacademic text (Lowrider, top) and academic text (TutorVista, bottom).

derives from m embership in a community th a n s p e c if i c c la i m s . Ma i n t a in i n g th

committed t o a shared epistemology; this e i mp e r s o n a l authoritative s tance creates

(“Jason you are r ight on bro ”).

stance is expressed t hrough a r eduction a distanced tone that is often puzzling to

Though both t he Lowrider authors are in the use of personal pronouns, a

adolescent r eaders and is extremely difficult for

writing t o i nform, they are not

preference for epistemically warranted

adolescents to emulate in wr i ti n g .

assuming the i mpersonal aut

evaluations (such as “ri g o r o u s s t u d yPerhaps the simplest basis f or comparing

horitative voice that is characteristic of ” and “qu e s t i o n a b l e a n a l y s i s

the Lo wr i d e r a n d Tu t o r Vi st a t e x t s

academic language. They claim t heir ”)overpersonallyexpressi ve evaluations (s i s t o c o n si d e r h o w rare in other

authority t o provide information about uch as “great st udy ” and “funky analys contexts are the words t hey use most

the advant age of torque over

is”), and a focus on general rather

horsepower adjust ments on t he basi

s of personal experience. The

scientist’sauthoritativestance,ontheoth

erhand,

Lever arm

Torque is the product of the magnitude of the force and the lever arm

of the force. What is the significance of this concept in our everyday

life?

Dependence of torque on lever arm

To increase the turning effect of force, it is not necessary to increase the

magnitude of the force itself. We may increase the turning effect of the force

by changing the point of application of force and by changing the direction

of force.

Hinge

Axis of

rotation

Let us take the case of a heavy door. If a force is applied at a point, which

is close to the hinges of the door, we may find it quite difficult to open or

close the door. However, if the same force is applied at a point, which is at

the maximum distance from hinges, we can easily close or open the door. The

task is made easier if the force is applied at right angles to the plane of

the door.

When we apply the force the door turns on its hinges. Thus a turning effect

is produced when we try to open the door. Have you ever tried to do so by applying

the force near the hinge? In the first case, we are able to open the door with

ease. In the second case, we have to apply much more force to cause the same

turning effect. What is the reason?

The turning effect produced by a force on a rigid body about a point, pivot

or fulcrum is called the moment of a force or torque. It is measured by the

product of the

force and the

perpendicular

distance of the

pivot from the line

of action of the

force.

force = Force x Perpendicular distance of the pivot from the

force. The unit of moment of force is newton metre (N m).

In the above example, in the first case the perpendicular distance of the

line of action of the force from the hinge is much more than that in the second

case. Hence, in the second case to open the door, we have to apply greater

force.

M

o

m

e

n

t

o

f

a

on May 13, 2010 www.sciencemag.orgDownloaded from

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 328 23 APRIL 2010 451

Science, Language, and

Literacy

frequently. The rarest words used i n t he

Science t eachers are not generally well

Lowrider text are t he special term “lol o ”

prepared t o help t heir students penetrate

and its alternative form “low r ider, ”“up g r a the linguistic puzzles that science texts

d e , ”“carb, ”“HP, ”“exhaust,”“spin, ” and

present. They of course recognize that

“torque. ” Only two words from the Academic teaching vocabulary i s key, but typically

Word List (10 ), a list of words used

focus on t he science vocabulary ( the

frequently across academic texts of diff

bolded w ords in the t ext), often without

erent disciplines, appear in this passage.

recognizing that those bolded words are

The Tu t o r Vi s t a t e x t r a r e w o r d s i n defined with general-purpose academic

words t hat s tudent s also do not know.

c l u d e “magnitude,” “perpendicular,

”“lever,”“pivot, ”“hinge,”“fulcrum, ” and

Consider the TutorVi st a definition of

“torque,” and it uses t he academic words

torque: “To r q u e i s t h e p r o d u c t o f t h

e magnitude of the force and the lever arm

“tas k , ”“maxi mum ,”“significance,” and

of the force. ” Many 7th graders are

“illust rati on. ” The difference i n word s

election reflects t he convention i n t he

unfamiliar with the t erms “magnitude ” and

more academic text of presenting precise

“lever ”;andsome proportion will think t hey

understand “product,”

information in a dense, concise manner.

Nominalizations are a grammatical pr

ocess of converting entire s entences (such as

“Gutenberg invented the printing press

”)intophrasesthat can then be embedded in

other s entences (such as “Gutenberg ’s

invention of the printing press revolutionized

the dissemination of information”).

Nominalizations are crucial to the conciseness

expected in academic language. I n t he Tu t o

r Vi s t a s e n t e n c e “We m a y i n c r e a s e

t h e t u r n ing eff ect of the f orce by changing

the point of application of f orce and by

changing the direction of force,”“application”

and “direction” are nominalizations

representing entire pr opositions. “Application ”

is shorthand for “where w e apply,” and

“direction ” is shorthand for “how we direct.”

Thus , although this sentence has t he same

apparent s tructure as “We c a n g e t a s m i l

e f r o m a b a b y by changing his diaper and

by patting his back,” the processing load is

much higher. “Increase” in the original s

entence i s a verb referring to a r elation

between two quantities, whereas “get ” in the

baby-sentence adaptation refers to an action

or effect in the r eal world. “Diaper ” and “back

” are physical entities subjected to actions,

whereas “application ” and “direction” are

themselves actions that have been turned into

nouns. Part of the complexity of academic

language derives f rom the fact that we use t

he syntactic structures acquired f or talking

about agents and actions to talk about entities

and relations, without recognizing t he

challenge that t hat transition poses to the

reader. I n particular, in science classes we m

ay expect students t o process t hese

sentences without explicit instruction i n t heir

structure.

“force,” and “arm ” without r ealizing t hat t

hose terms are being used i n technical,

academic ways here, w ith m eanings quite di

ff erent from t hose of daily l ife. Yet this

definition, with its s ophisticated and unfamiliar

w ord m eanings, i s t he basis f or all the rest

of the TutorVista exposition: the trade-off

between magnitude and direction of force.

Efforts to he lp s tudent s understand

science cannot ignore their need to

understand the words used to write and talk

about science: the allpu rpo s e a ca dem i c

w or ds a s wel l as t he d isci pline specifi c

ones. Of course some students acquire

academic vocabulary on their own, if they

read widely and if their comprehension skills

are strong enough to support inferences

about the meaning of unknown words (11 ).

The fact that many adolescents prefer

reading Web sites to books (12 ), however,

somewhat decreases access to good models

of academic language even for those

interested in technical topi cs. Thus, t hey

have f ew opportunities to learn the academic

vocabulary that is c rucial across their

content-area learning. It is also possible t o

explicitly teach academic vocabulary t o m

iddleschool s tudents. Word Generation i s a

middleschool program developed by the

Strategic Education Research Partnership t

hat embeds allpurpose academic words i n i

nteresting topics and provides activities for

use in math, s cience, and social studies as

well as English l anguage arts classes i n w

hich the target w ords are used ( see t he We

b s i t e f o r e x a m p l e s ) ( 13 ). Among the

academic w ords taught in Word Generation

are t hose used to make, assess, and defend

claims, s uch as “data,”“hypothesis,”“affi r m

,”“convince,”“disprove,” and “interpret. ” We d

e s i g n e d Wo r d G e n eration to f ocus on

dilemmas, because these promote discussion

and debate and provide motivating contexts

for s tudents and teachers t o use t he target

words. For example, one week is devoted to

the t opic of whether junk food should be

banned from sc hools, and another t o

whether physician-assisted suicide should be

l egal. Discussion i s i n itse lf a key

contributor to science learning ( 14) and to

reading comprehension (15 , 16 ). Words l

earned through explicit teaching are unlike ly

to be retained i f t hey are taught in lists r

ather t han embedded i n m eaningful texts

and i f opportunities to use t hem i n

discussion, debate , and writing are not

provided.

It is unrealistic to expect all m iddle- or

precision of word choice, and use of

highschool s tudents t o become proficient

nominalizations to refer t o complex processes

producers of academic language. M any

—reflect the need to present complicated

graduate students still struggle t o m anage t he ideas in effi cient ways. Students m ust be abl

authoritative s tance, and t he self-presentation e to r ead texts that use these features if they

as an expert t hat justifies it, i n their writing. And are t o become independent learners of

it is i mportant to note t hat not all f eatures

science or s ocial s tudies. T hey m ust have

associated with the academic writing style ( suchaccess to t he all-purpose academic

a s the use of passive voice, impenetrability of vocabulary that i s used t o talk about

prose constructions, and indifference t o literary knowledge and that they will need to use i n m

niceties) are desirable. But the ce ntral fe atures aking t heir own arguments and evaluating

of a cade m ic lan guage —grammatical

others’ arguments. Mechanisms for t eaching t

embeddings , s ophisticated and abstract

hose words and the ways that scientists use t

vocabul ary,

hem s hould be a part of the s cience

curriculum. Collaborations between desi gners

of science curricula and l iteracy scholars are

needed to develop and evaluate methods fo r

h el p i n g s t ud e n t s m a s t e r t h e l a n gu

a g e of s ci e nc e at the u nd ergraduate and

h igh-school levels a s well as at the mi

ddle-school level that Word Generation is

currently serving.

Advancing Adolescent Literacy, Time to Act: An Agenda

for Advan cing Adolescent Literacy for College and

Career Success (Carnegie Corporation of New York,

New York, 2010); http:/ /carnegie.org/ fileadmin/

Media/Pu blications/PDF/t ta_Main.pdf. 2. J. Johnson,

L. Martin-Hans en, Sci . Scope 28 , 12 (2005). 3. M. A.

K. Halliday , paper presente d at the Ann ual Internation

al Language in Education Conferen ce, Hong Kong,

December 1993. 4. M. J. Schleppegrell, Linguist. Educ.

12 , 431 (2001). 5. M. A. K. Halliday , J. R. Martin,

Writing Science : Literac y and Discursive Power (Univ.

of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 1993). 6. A. Bailey,

The Language Demands of School: Putting Academic

English to the Test (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT,

2007). 7. R. Scarcella, Academic English : A

Conceptual Framework (Technical Report 2003-1, Univ.

of California Linguistic Minority Research Institu te, Irv

ine, CA, 2003) . 8. C. Snow, P. Uccelli, in The

Cambridge Handbook of Literacy , D. Olson , N.

Torrance , Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, New York,

2008), pp. 112 – 133. 9. Z. Fang, Int. J. Sci . Educ. 28 ,

491 (2006).1 0 . A . C o x h e a d , T E S O L Q . 3 4 ,

213 (2000 ). 11. J . L a w r e n c e , Read.

P sy chol. 30 ,445 ( 2009). 12. E. B. Moje,

M. Ov erb y, N . T ysvaer, K . Mo rri s, H arv.

E d u c . Rev. 78 , 107 (2008). 13. C. Snow, J. Lawre

nce, C. Wh ite, J. Res. Educ. Effectiven ess2, 325

(2009 ); www.wordgener ation.org. 14. J. Osborne,

Science 328 , 463 (20 10). 15. J. Lawrence, C. Snow, in

Handbook of Reading ResearchIV, P. D. Pearson, M.

Kamil. , E. Moje, P. Affle rbach, Eds. (Routledge

Education, London, 2010).

16. P. K. Murph y, I. A. G. Wilkinson, A. O. Soter, M.

N. Hennessey, J. F. Alexander, J. Edu c. Psychol. 62,

387 (2009 ).

17. P r e p ar a t io n o f t h is p ap e r w as m ad e p

os si b l e b y co l la b o r at i on s s u p p o r t e d b y t

h e St r at e g i c Ed u ca t io n R e s e ar ch P ar t ne r

s hi p an d re s e a rc h f u n d e d b y t he Sp e nc e r

F o u n d at i o n, t he W i ll i am an d F l or a H e w le

tt F o u nd at i on , t h e Ca rn e g i e Co r p o ra t io n

o f N e w Y o rk , an d t he I ns t i t u t e f o r E d u c at

i on Sc i e n ce s t hr o u g h t h e Co u n ci l o f G r e

at Ci t y S ch oo l s. T ha nk s al s o t o w ww . Tu t or

V i st a . co m f o r p e rm i ss i on to re p r in t t he ir le

s s on o n t o r q u e .

10.1126/science.1 182597

23 APRIL 2010 VOL 328 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org452

mag.orgDownloaded from

References and Notes1. Carnegie Council on