ONLINE APPENDIX A. Causal Ordering of the Study Variables

advertisement

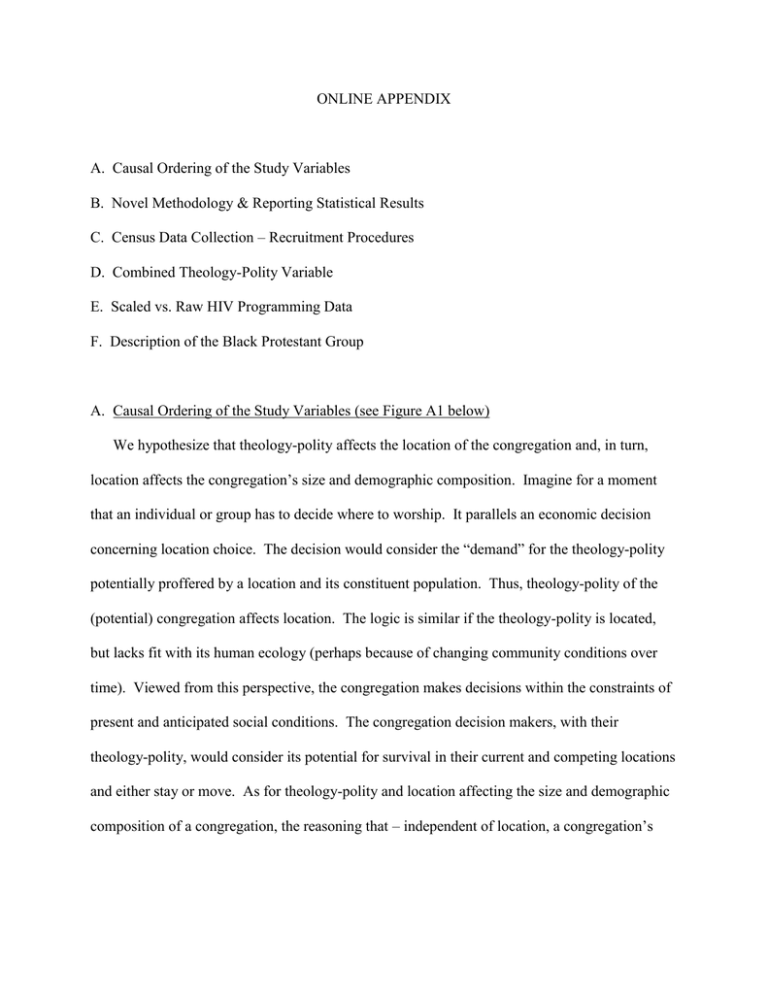

ONLINE APPENDIX A. Causal Ordering of the Study Variables B. Novel Methodology & Reporting Statistical Results C. Census Data Collection – Recruitment Procedures D. Combined Theology-Polity Variable E. Scaled vs. Raw HIV Programming Data F. Description of the Black Protestant Group A. Causal Ordering of the Study Variables (see Figure A1 below) We hypothesize that theology-polity affects the location of the congregation and, in turn, location affects the congregation’s size and demographic composition. Imagine for a moment that an individual or group has to decide where to worship. It parallels an economic decision concerning location choice. The decision would consider the “demand” for the theology-polity potentially proffered by a location and its constituent population. Thus, theology-polity of the (potential) congregation affects location. The logic is similar if the theology-polity is located, but lacks fit with its human ecology (perhaps because of changing community conditions over time). Viewed from this perspective, the congregation makes decisions within the constraints of present and anticipated social conditions. The congregation decision makers, with their theology-polity, would consider its potential for survival in their current and competing locations and either stay or move. As for theology-polity and location affecting the size and demographic composition of a congregation, the reasoning that – independent of location, a congregation’s Size (Average Attendance) TheologyPolity1 Location (Urban vs Suburban) SocioDemographics (Composition): Age Race Education Family Type Operational Resources: Paid Clergy & Staff Worship Site Changed Site Years Existed Religious/ Worship Activity (Number of Weekly Worship Gatherings) Service/Community Work: Spiritual Counseling General Service Health Programs (non-HIV) Handicap Access Guest Speakers HIV Programs / Services: Education / Prevention Counseling Testing Figure A1. Path diagram of relationships between congregational theology-polity and HIV prevention/counseling programs belief system and organization appeals to and attracts members to differing degrees and of certain types and thus determines the size and demographic composition of the congregation – is so well-documented as to have attained the status of conventional wisdom in the sociological study of religion. Similarly, there is an overwhelming body of literature that corroborates that central city and suburban locations affect the size and composition of their populations via constraining a surrounding population’s decisions regarding where to move. In turn, the size and composition of a location’s population becomes the market that theology-polity congregations penetrate to varying degrees; of course, some theology-polity types are more niche-oriented than others. There is no clear guidance from the literature on the causal ordering of the variables of interest, and one may feel pushed to use these variables as correlates versus predictors. The purpose of causal models is to test hypotheses about the causal ordering of variables. In our study, we test a prediction of theology/polity determining congregation’s location and sociodemographic composition, and we open a way for others to test other hypotheses about the relationship between these variables. B. Novel Methodology & Reporting Statistical Results This analysis involves compromises in testing alternative hypotheses about the causal ordering of variables, but at the same time, it constitutes a substantial methodological advance. Path analysis generally relies on coefficients from ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions (or coefficients that have the sense of OLS estimates, but estimated based on other statistical procedures, such as maximum likelihood estimation). While correctly presented here in a role subsidiary to the theoretical ideas, we developed and used a method of combining results from a variety of regression models. The procedure allows combining results of regression procedures that produce better estimates of effects at the various steps in the sequence of variables – e.g., binary, ordinal, and multinomial logistic regressions, Poison and negative binomial regressions, and OLS regressions – to test direct and indirect effects with intuitively meaningful, comparable coefficients. Also, because of these complexities, we do not present the results for each path implied by the model. Rather we present a parsimonious version of the findings, focusing on the effects of theology-polity on HIV programming. This can be viewed as a triage approach that underscores the priority of the mediators. This paper makes an important, innovative methodological contribution to structural equation modeling (SEM) by expanding the capability of path analysis so that theory testing can address causal models involving more than only OLS regressions. The strength of path analysis is that it yields information on how 2 variables are related by partitioning their covariance (correlation) into spurious, direct, and indirect effects. In general, the indirect effects are most informative. These are the antecedent variable of interest effects on a dependent variable of interest that are hypothesized to occur through specific mediating variables. The tests of these mediating effects are explicit tests of hypothesized causal mechanisms. They make path analysis a highly sophisticated procedure and a basic component of articulated SEM. However, an indirect effect involves manipulating coefficients from at least 2 equations. In general, a particular path operating through 1 or more mediating variables is statistically significant if all the coefficients involved in path’s steps are statistically significant. Again, each coefficient on the path’s steps come from different equations. Any indirect effect involves at least 2 test statistics and 2 p values. The “summary” or “triage” method presented in this paper involves combining information from 2 equations. However, there are added complications due to the complexity of the phenomena being studied. One notable complexity is the 6-category typology making up theology/polity. As with any categorical predictor in regression models, a nominal variable requires [(n*(n-1))/2] paired comparisons to establish the statistically significant differences between 2 categories; in this case, 15 paired comparisons – giving rise to Table 4’s 15 boxes marking failure to reject the null, null-rejected 2-tailed test, and null-rejected 1-tailed test (alpha = .05) for each effect of theology/polity on HIV programming explored (and presented in Table 3), except those operating through the sociodemographic composition of congregations. These tests are accomplished by rotating 1 “reference category” to be omitted from a run of the equation; thus, these 15 tests required running 5 versions of the same equation. The sociodemographic composition variables were more complex because the influence of theologypolity on each dimension of composition required multinomial logistic regressions that produced 2 equations and required an additional run to complete significance comparisons among 3 categories. These comparisons were nested within the 5 versions of equations necessary to test theology-polity type differences. The upshot is that many test statistics were examined and their presentation would require many tables and make the work less comprehensible. A statistician can follow the logic of the procedure and, with experience in path analysis with categorical variables and with multinomial logistic regression, will know that the number of test statistics examined will be numerous. Although not a quick read, researchers should be able to follow how the numbers presented are arrived at and only need to take on faith that we have not erred in looking at p values in our output from runs. C. Census Data Collection – Recruitment Procedures Interviewers were trained to make multiple call-backs for various reasons including inconvenient time, a message was left, or the call was unanswered after 10 rings. Those congregations requiring call-back were called on different days and at different times during the day. The interviewers were instructed to use their judgment in regard to the number of voice messages left. Usually 1 message was considered sufficient, but further calls and messages were warranted in case of a different “follow-up” interviewer or when trying to reach a specific person. We avoided calls to congregations close to and during major holidays based on a congregation’s religion. We also followed up once after a refusal. We tried calling the second time on a different day/time of day to increase the probability of speaking with a different person or catching somebody at a better time. We did not conduct in-person follow-up. However, we sent a follow-up postcard and we located email addresses for some congregations via the internet and personal contacts in the community and contacted those congregations via email. The follow-up resulted in 28 additional census completions. D. Combined Theology-Polity Variable Using ordered logistic regression analyses, we contrasted regressions of “having HIV program[s]” on theology and polity as separate variables (an additive model) and on theology and polity combined into a typology (an interaction model). The interaction-based typology showed a marked, statistically significant improvement over the additive model. Thus, we used a combined theology-polity (interaction) variable. E. Scaled vs. Raw HIV Programming Data The scaled data “correct” the raw data based on the census items by differentiating between single and multiple-type program offerings (compare Table 2 with the table below). For example, based on the HIV programming scale, 12% of Black Protestant congregations offered education/prevention only, 9% offered education/prevention and counseling, and 15% offered all 3 types of programs. In contrast, in raw data, 33% of Black Protestant congregations offered education/prevention, 18% counseling, and 15% testing (summing to 36% offering any programming). F. Description of the Black Protestant Group There were 33 congregations in the Black Protestant category (7% of all congregations); 31 were congregational and 2 were episcopal in terms of polity. The majority (64%; N=21) were affiliated with a denomination/convention: 14 Baptist (including National, United, American, Southern, and Ohio conventions), 3 Church of God, 2 African Methodist Episcopal, 1 Pentacostal, and 1 Non-denominational (affiliated with Bible Way Church); 36% (N=12) were not affiliated with a denomination/convention. In terms of theological orientation, 39% of the Black Protestant congregations were “right in the middle”; 24% were “more on the conservative side”; 18% were “more on the liberal side”; 9% were “clearly liberal”; and, 6% were “clearly conservative.” In terms of religious identity/culture, 33% claimed no specific religious culture/identity, 18% were Evangelical, 15% mainline, and 9.1% each Liberal and Charismatic; the remaining were spread through other categories. The city-suburb split was 70%-30%. All but 2 (94%) worshiped in a church/synagogue/temple vs. some other building. Most (64%) of the Black Protestant congregations offered no HIV programming; 15% offered education, counseling, and testing programs; 12% offered education programs only; and 9% offered education and counseling programs. Subgroup analysis was limited due to small numbers. Generally, more congregations that were affiliated with a denomination/convention offered HIV programs/services versus congregations that were not affiliated with a denomination/convention (43% vs. 25%). Among the 14 Baptist congregations, 9 offered no programs, 3 offered education, counseling, and testing programs, 1 offered education programs only, and 1 offered education and counseling programs. There was not much difference between congregations that were “more on the conservative side” and congregations that were “more on the liberal side” – half of each offered no HIV programs/services; by comparison, 60% of congregations that were “right in the middle” offered no HIV programs/services. In terms of religious culture/identity, none of the 6 Evangelical congregations offered HIV programs/services whereas 5 (45%) of those with no specific culture/identity offered some type of HIV programs/services. Also, more Black Protestant congregations located in the central city vs. a suburb (39% vs. 30%) offered HIV programming. The sociodemographic and organizational characteristics of the Black Protestant category vis-à-vis the other theology-polity groups are shown in the table below. Comparison of theology-polity groups by selected characteristics Central city location (%) Years in existence (mean [median]) Changed worship site over time (%) Size (regular attendance; mean [median]) Number of paid clergy & staff (mean [median]) Number of weekly worship sessions (mean [median]) Predominantly Black (%) Predominantly more than high school education (%) Predominantly ages 50+ (%) Predominantly families with children (%) Roman Catholic/ Episcopal Mainline Protestant/ Episcopal Mainline Protestant/ Congregational Conservative Protestant/ Congregational 33 106 [104] 33 1750 [1950] 10 [7] 2 [2] 7 47 16 11 25 117 [120] 53 559 [343] 8 [6] 2 [1] 4 60 38 11 30 118 [123] 55 355 [259] 6 [6] 2 [3] 3 69 44 6 13 63 [51] 71 426 [265] 6 [4] 2 [2] 2 38 16 15 Black Other Episcopal Protestant/ & Congregational Episcopal & Congregational 70 66 [62] 79 602 [378] 10 [8] 2 [2] 85 30 3 9 9 85 [54] 82 949 [627] 6 [3] 2 [2] 9 91 27 18