Prepared prior to the meeting on PLCs. All items were... were: Dr. Julia Rankin Morandi

advertisement

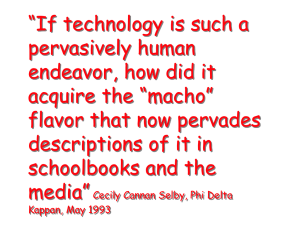

Prepared prior to the meeting on PLCs. All items were not discussed. Many others were: Dr. Julia Rankin Morandi April 30, 2009 Comments for Cecily Selby Panel1 As the Director of Science of NYC schools, I met many amazing people, none so influential/important to my personal and professional life as Cecily Selby. We first met at an event at the Hall of Science, an organization she and her family have been intimately involved in for years. We immediately bonded, sharing a love of science and respect for science education. She took me under her wing, introducing me to many prominent scientists, politicians, researchers and educators who cared deeply about science and science education as she did. Cecily and I spent many hours devising ways to unite interested parties around science education. We invited people to her home to speak of diverse topics such as evolution, patterns of democracy that do or do not support science education in America and always inquiry and the importance of evidence. With Cecily, the conversation is always intense, the questions always probing, her quest for evidence to support science relentless. She brings people together for stimulating discourse on topic of great depth. Today I am here to talk about Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), an appropriate topic to honor Cecily. When I think of PLCs, I think of Cecily. She is the ultimate connector. On my visits to the city, we meet with our own informal PLC the ‘NYC Ladies of Science’, a group of wonderful women dedicated to various forms of science and science education with a connection to NYC. PLCs are dynamic systems that are sensitive to change. They take a variety of forms and have a life of their own. Etienne Wegner describes such systems as collaborative communities of practice. Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. They are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavor. In California, I work closely with 5 K-12 teacher directed networks (Target Science for Urban Education Partnership, UEP) in Los Angeles and 9 university based PLCs under a science teacher retention grant with the California Science Project, CSP. According to Eric Hirsch, director of special projects with The New Teacher Center at the University of California at Santa Cruz, teachers want control over their own learning. One of the powers of a PLC is the ability to choose what to focus on as a community. When given the choice, teachers in UC San Diego began to work together to organize their labs and sharing websites, eventually focusing on academic testing and scores. But it was their choice. They decided when and how to focus and invited the college professors to assist. Another is the ability to choose where their PD should occur. In the PLC with CSU Northridge, the decision was made to have the professors bring the PD to the school. They meet in grade level teams to design their own PD that is administered at the school site. At Urban Advantage in NYC, another program, I helped develop, teachers meet at the informal institutes such as the Museum of Natural History and the NY Hall of Science to work with researchers in science. I interviewed many teachers for Sheila Tobias for her book that will be released April 15 entitled, Science Teaching as a Profession. I found teachers wanted to be viewed as professionals and felt that their participation in the PLCs formed with CSP and UEP did in fact give them the tools to help students achieve those ‘aha’ moments and the ability to feel part of an intellectual community with professors of science and science education, other teachers and practitioners in their field of expertise. For the Partnership for Teacher Excellence in NYC, I was able to collaborate with NYU, CUNY and the NYCDOE on the recruitment of science undergraduates into the teaching profession. I had the opportunity to speak to science undergrads considering the teaching profession. They were concerned about no longer being able to do real science. The same was true of many of the teachers I spoke with in NYC and California. In conversations with science and science education professors at various universities, we discussed the need to include teachers in the development of research questions. In “Learn by Doing” Labs at CSU Chico and Cal Poly at San Luis Obispo, teachers in their PLCs bring their students to science labs at the universities to learn alongside their students. NYU is seeking funding to expand on a similar program. Graduate and undergraduate students help deliver science content. These are the types of programs we need, programs that bring the larger community (undergrads, grads, science educators and scientists) together to support teachers. At a recent ASTE convention, science education professors expressed their need to publish or perish. I commented, “publish with teachers or perish”; that the secret to their success and the success of our schools is to form research partnerships with teachers. Not to simply provide what they think they need but to work in unison to develop strong research questions that impact upon teaching and learning. I met some amazing people through Cecily and continue to be impressed by her farreaching grasp. Just last week at the California Institute of technology, I had the opportunity to converse with Alice Huang, future president of AAAS, a colleague and neighbor of Cecily and her husband at Woods Hole. She spoke highly of Cecily, as did a former leader in the Girl Scouts at another totally unrelated event in Long Beach that same week. We need to rally around the beliefs and practices of Cecily Selby to improve the understanding of science by all members of society. In particular, we need to support our science educators so that they may adequately share that knowledge by treating them like science professionals. They need to be embraced by all members of the scientific community Some of these comments came out in various sections. Not exactly sure which: 1. In NYC, we developed a Common Scope and Sequence for 1400 schools in five boroughs! The reason we did this was to promote equity. We felt it was important that all students gain access to the same materials. With mobility so high in inner cities, it helped ensure equal access for all. I would love to be involved in a national movement to do the same. 2.?? Partnerships are important. We need to feel connected and work collaboratively. As the Director of Science for NYC, I faced the same issues as those I experienced as the Director of Science in Bridgeport only on a much larger scale. Seeking assistance, I worked with NSTA to develop the Urban Science Education Leaders (USEL) to bring science directors and others interested in the unique features of urban schools together. That program has grown and continues to gain momentum. Questions at end. One of the issues we see happening in education is the control within cities by business leaders without input from educators. It was done in NYC and now in LA. Again, showing a lack of respect for education community. We need to work together to make changes that effect education. Not separately.

![Download [epdf] Book The Hidden Life of Cecily Larson by Ellen Baker](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/027346769_1-af4d9f7f6231c73111da452bc7b38194-300x300.png)