Here is the link for a download.

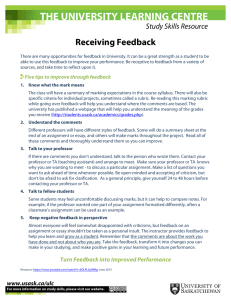

advertisement