Appropriate and Inappropriate Sources

advertisement

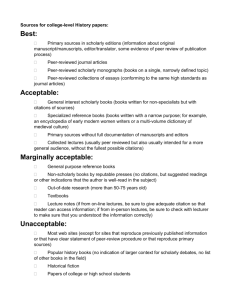

APPROPRIATE AND INAPPROPRIATE SOURCES Secondary Sources: One of the skills that you will need to have to write good college-level papers is the ability to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate sources for research. The form of the source is usually less important than the way that the information in the source has been gathered and presented. It is also possible for a source to contain "correct" information, but not be an appropriate source for research. For example, an internet source that contains footnotes with references to primary sources, scholarly debates, and scholarly works, and is logically and fairly argued would be acceptable, while another source (whether book, journal article, or internet page) might include many of the same facts but not be acceptable, because the author did not give sources for information or did not put the information into the larger context of other research in the field. Some general characteristics of appropriate secondary sources: citations of sources (footnotes, endnotes, or parenthetical references) use of both primary (first-hand) and secondary sources use of recent scholarly works (relative to the original publication date--for a work published in 1960, sources from the 1950s would be "recent" but they would not be recent for a work published in 2000, though the 2000 work might contain some earlier references as well) evidence that the author has looked at material in archives and/or material written in other languages putting facts into a larger historical context making an argument about the facts (rather than just "telling a story") assumption of an adult audience for the source indication that the source has been peer-reviewed (approved for publication by someone who is an expert in the field). Generally, scholarly journals (such as The American Historical Review) are peer-reviewed as are books by university presses (such as University of Chicago Press). Some general rules for identifying inappropriate secondary sources: no citations of sources use of only tertiary sources (textbooks or broad surveys of a particular time or place) use of out-of-date sources (if more than half of the sources were more than 20 years old at the time of publication, then one might doubt how connected the author was with current scholarship) no reference to primary sources giving facts without a larger context or discussion of their historical significance name-calling or otherwise implying that those who have come to different conclusions are not just mistaken, but somehow stupid, immoral, or otherwise deficient as human beings sources clearly designed as overviews for beginners (high school students, college students in an introductory Western Civ course) no date of composition of the source anonymous works (meaning that no one is putting his/her good name behind the accuracy of the information) Primary sources: Primary sources are sources that are immediate to the event being investigated. They may be official documents that record a specific event (treaties, marriage contracts, etc.), personal accounts by eye-witnesses to an event (diaries, letters. etc.), or cultural texts that reveal something about the attitudes of people living at the time (epics, lyric poetry, etc.). For primary sources, unlike secondary sources, there is less a question of the appropriateness of the sources, than of whether the editions of the sources accurately reflect what the author(s) originally said. For example, if a modern editor has mistranslated material or only included those parts of the source that support a particular argument, then that source would be less valuable than a full translation of the text by a (relatively) unbiased editor/translator. Some general rules for identifying full and authentic primary sources: date of composition within a short time of the events being studied (the further back in history, the rarer good primary sources are and the less picky historians can afford to be, so in the 1500s, something written within 50 years of the events might be considered pretty good, but for the 1900s, something written more than a year or two after the event might be considered faulty) author who was an eye-witness to the events (or a document that was a legally binding record of the events) full text of the source discussion of potential problems in putting forward a good edition or translation (either in an introduction, in an appendix, or in notes by the editor/translator) Some general rules for identifying questionable primary sources: date of composition long after the events being studied (or not indicated at all) excerpts only no notes or other comments on how the text came into being or came down to us no identification of editor/translator Questionable sources can still be used if no full and authentic primary source is available, but the student should be aware that the source might not accurately reflect the author's full meaning. A good way to check on a source would be to see what the secondary literature says about it. If it is not discussed at all or if several reviewers of the source have complained about its accuracy, then the student might not want to rely on that source too heavily. Even full and authentic primary sources might present problems (if the original author was biased or ignorant or just expressed ideas in a way hard for us moderns to understand), but questionable sources have an added level of possible confusion for the beginning researcher.