21_ECEN.pptx

advertisement

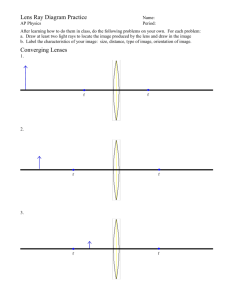

ECEN 4616/5616 Optoelectronic Design Class website with past lectures, various files, and assignments: http://ecee.colorado.edu/ecen4616/Spring2014/ (The first assignment will be posted here on 1/22) To view video recordings of past lectures, go to: http://cuengineeringonline.colorado.edu and select “course login” from the upper right corner of the page. Lecture #21: 3/03/14 Real and Virtual Objects A real image is created by actual rays, which could be intercepted by a screen, where the image would be seen: Optical System Screen position for image viewing When we block those rays with a lens, say, the real image is no longer formed, but becomes a virtual object for that lens, which may create a real image at another location: Optical System Virtual Object Screen position for new image viewing Real and Virtual Objects P P’ Optical System Any two rays (from the same object point) which converge define the corresponding image point. When we intercept those rays with a lens before the image position (turning the image into a virtual object), only the ‘graphical’ subset of the rays can be traced through the lens without calculation: A B f f’ C A: Ray parallel to the axis passes through the focal point after refraction. B: Ray passing through the focal point is parallel to the axis after refraction. C: Ray passing through the center of the lens is undeviated after refraction. Homework Problems Light guiding in a glass rod: a2 n=1 a1 a1 ’ n The problem asks you to find the maximum angle, a1, which still results 1 in TIR in the rod – in other words, the maximum angle for which a2 sin1 n First, it’s helpful to derive a relationship between a1 and a2: a1 90 a2 sin(a1 ) cos(a2 ) sin(a1 ) n sin(a1 ) n cos(a2 ) 1 a1 sin1 n cos sin1 n But, when we plug in n=1.52 the answer becomes: a1 sin1(1.447) So obviously there is no a1 which results in a2 being the critical angle. Does this mean that the rod can’t guide light? No, because if a1=0, light will obviously go straight down the rod. We can resolve this by setting a1=90o: we calculate a2=48.86o, which is greater than the critical angle, sin-1 (1/1.52)=41.14o, so what this means is that ANY light reaching the rod face will be refracted into the rod such that it will be guided. In engineering, it is a good idea to subject your conclusions to a ‘reality check’: Nearly everyone has seen decorative lamps and displays that use glass (or plastic) rods to guide light: So, the conclusion that a glass rod cannot guide light runs counter to our experience and hence the conclusion should be evaluated more closely. The Coronagraph: A significant problem solved with graphical ray tracing (and ingenuity) Problem: How to image something dim that is close (in angular terms) to a much brighter object? Examples: The Sun’s corona, when the Sun is not eclipsed by the Moon: A planet orbiting a star: In both cases, the radiance differs by a factor of millions to one. Optical systems, however, typically have a SNR of ~100:1 The Coronagraph First Attempt: Image the objects on a plane that contains an occulting disk to block the bright object, but let the dim object pass, then re-image the dim object. Light from bright object 1st Image Plane 2nd Image Plane Image of Dim Object Light from dim object Bright Object Image Stop The Coronagraph Why it doesn’t work: The system stop and entrance pupil (the first lens, in this example) is brightly and uniformly illuminated by the bright object. Hence, there is significant diffraction from the edges of the entrance pupil, which is spread over both image planes, and not removed by the Image Stop: Diffracted Light from Entrance Pupil Essentially, the edges of the stop have become secondary light sources, due to diffraction. This light might only be a fraction of a percent of the bright object’s light, but that is enough to obscure an image of an object that is thousands (or millions) of times dimmer. The Coronagraph The solution is called the ‘Lyot Stop’: Diffracted Light from Entrance Pupil Lyot Stop: (at image of entrance pupil) Light from dim object is passed to image plane. Diffracted light from bright object is stopped. What is happening here is that the entrance pupil (the first lens, in this case) is re-imaged at the Lyot Stop plane. Hence, the light that diffracts from the edges of the entrance pupil is re-imaged into a bright ring of light at the Lyot plane. The Lyot stop is just an annular opaque ring which blocks the (reimaged) diffracted light. The Coronagraph This method can be carried out for multiple iterations: 1. The bright object is imaged to a plane, where an opaque stop blocks it. 2. The first brightly illuminated lens (aperture) diffracts light from near its edges, producing a secondary source of interfering light. a. The offending lens is re-imaged and an annular stop blocks the diffracted light. 3. The 2nd lens (which re-images the first lens) may also be too brightly lit, and diffracts interfering light from its edge. a. The 2nd lens is re-imaged by a third lens and an annular stop blocks the edge-diffracted light. And etc…. Eventually, scattered light from the surface and/or bulk of the lenses will dominate the stray light. Separating this light from the image light optically requires other techniques, such as spatial filtering. Laying out a Coronagraph b a c K1 d 1. The first lens must image the bright object to the first stop: K2 e 1 a K1 2. The second lens must image the entrance stop to the Lyot stop: 1 1 K2 b d 3. The second lens must also image the first stop (image plane) to the second image plane: 1 1 K2 e c These equations constrain, but do not determine the design: The designer must find reasonable values to use. Laying out a Coronagraph Another serious design constraint is to determine the rate at which the PSF from the first lens decays, and whether that is enough to mask the image from the dim object(s). The larger the first lens, the smaller the angular extent of the PSF, so the PSF dropoff and angular separation between dim and bright objects constrain the minimum diameter of the first lens. The difficultly of building low F/# lenses means the the focal length will also increase with the diameter. The Fourier Transform of a circular aperture can be worked out analytically and its square is the intensity of the Airy Pattern. For an aperture with radius a, the intensity of the Airy Pattern as a function of angle is: 2J1 ka sin I I0 ka sin 2 Where J1 is the Bessel function of the first kind, order 1, and k 2 The design methodology here is: • Decide what minimum angle (away from the Sun or star) is required. • Determine the ratio of the Sun/Star irradiance in the image to the target irradiance. • Find the aperture radius, a, where the PSF drops to less than than ratio from the peak. • Based on reasonable F/# for the optics, determine the minimum focal length required. Laying out a Coronagraph The PSF intensity calculation allows us to define the required radius of the objective, a. Construction constraints (for apochromats, for example) determine the minimum focal length achievable, f; and that determines the needed size of the first image stop, D f a D This constraint results in Solar coronographs having focal lengths in the 10’s of meters range: Laying out a Coronagraph A similar calculation is required to determine the necessary size and focal length of the second imaging lens and the size of the Lyot stop: b a c K1 d K2 e Laying out a Coronagraph For detecting planets around other stars, the angular requirements result in extremely long focal lengths (100’s of km), so another approach is to use a phase mask at the prime focal plane in order to null out the star image: The phase mask can be considered a Fresnel Zone Plate, where the zones are calculated to null the on axis focus, rather than to enhance it. Slightly off-axis light is not nulled, so the planet’s image can make it through. This avoids the need to have an image stop, so allows a much more compact system. This image is from: A nulling wide field imager for exoplanets detection and general astrophysics, O. Guyon and F. Roddier, Astronomy & Astrophysics, V391, pp 370-395 (2002) Laying out a Coronagraph Another approach is one being taken here at CU: The ‘Star Shade’ is a separate spacecraft that IS a stop, ~10 m in diameter. It is to be positioned 10,000 km away from the space telescope such that it blocks the light from the target star, but not from the star’s planets. A key element in this line of research is to find aperture shapes which have extremely small amounts of diffracted light on axis – that is, they create extremely dark shadows. An example is the “Starshade” designs being created at CU: Read more at: http://newworlds.colorado.edu/starshade/ Optical Instruments: Telescopes Telescopes can be considered as an Objective lens creating a real image of distant objects and an eyepiece working as a magnifier to allow the eye to observe the real image: Image of Distant Object Image of Objective Lens One of the tasks of the eyepiece in a telescope is to re-image the Objective Lens into the space behind the eyepiece. Since the Objective Lens is the stop (limits the amount of light from the object), it’s image is the exit pupil of the system. The distance that this image is behind the eyepiece is known as the eye relief, and the user should try to match this image with their eye’s pupil. This allows all of the light that enters the Objective Lens to pass into the eye, producing the greatest brightness and field of view. Telescopes Objective Lens Image of Distant Object Exit Pupil Image of Objective Lens A telescope is an afocal system. However, as we have shown, a afocal system can produce a real image of a nearby object. In particular, the exit pupil is an image of the objective lens, which you can see by looking at the exit pupil from 15 inches or so away, while putting your finger in front of the objective lens – you will see a miniature image of your finger in the exit pupil. I works the other way around, as well. A binocular (or telescope) can be used as a field microscope, by putting the object at the exit pupil and observing the magnified image at the objective lens. Pupil Matching Objective Lens Image of Distant Object Image of Objective Lens The angular magnification is the ratio of the focal lengths of the objective to the eyepiece. Because the eyepiece is usually significantly shorter focal length than the objective, the ratio of the diameter of the objective to the diameter of the exit pupil is also about the same as the angular magnification. The size of the exit pupil determines if the telescope or binocular can be reasonably used at night. The Human eye’s pupil expands to ~ 5-7 mm diameter when darkadapted. If the exit pupil is significantly less, then no extra light will be coupled to the eye and the image will remain dark. The exit pupil diameter is ~ the ratio of the objective diameter to the magnification.