Promoting Fair Access: Final Report [DOC 648.00KB]

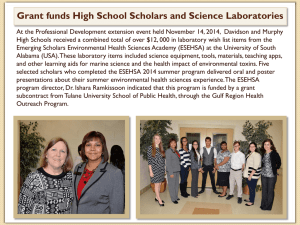

advertisement

![Promoting Fair Access: Final Report [DOC 648.00KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/014995420_1-1cf3ecb0a45b323f63309e0e8e5da9db-768x994.png)