What Works, Wisconsin: From good intentions to effective interventions for delinquency prevention

advertisement

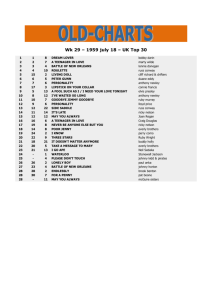

What Works, Wisconsin: From good intentions to effective interventions for delinquency prevention Wisconsin State Prevention Conference July 19, 2006 Cailin O’Connor, Steve Small & Mary Huser University of Wisconsin-Extension and University of Wisconsin-Madison What Works, Wisconsin Full report and additional information available at: www.oja.state.wi.us/jj Overview of today’s presentation What are evidence-based programs? What does it mean for a program to be “cost-effective”? What are some principles of effective programs? How can we use this knowledge to improve existing programs? What are evidence-based programs? A new class of programs that: Are based on a solid scientific and theoretical foundation Have been carefully implemented and evaluated using rigorous scientific methods Have been replicated and evaluated in a variety of settings with a range of audiences Have evaluation findings that have been subjected to critical review and published in respected scientific journals Have been “certified” as evidence-based by a federal agency or respected research organization History of evidence-based programs Medical practice and health care Public health Social work Clinical and school psychology Prevention science Other fields Number of evidence-based programs 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s Evidence-based program registries Number of registries is growing Most focus on a particular area of interest There is a great deal of overlap between evidence-based registries Common program labels Exemplary Programs (Department of Education) Effective Programs (CDC, NIDA, DHHS) Model Programs (SAMHSA, OJJDP Blueprints, Surgeon General) Proven Programs (Promising Practices Network) What Works (Child Trends) Why the interest in evidence-based programs? Body of scientific evidence has reached a critical mass Public accountability Efficiency (don’t need to reinvent the wheel) Increases the likelihood that programs will have the impact that they were designed to produce Evidence helps sell the program to funders, stakeholders and potential audiences Data may be available to estimate cost effectiveness Sample evidence from an evidence-based program Aggression and Hostility Index Aggressive and hostile behaviors 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 Control group 0.6 SFP 10-14 Program 0.4 0.2 0 6th 6th grade grade pretest posttest 7th grade 8th grade 10th grade SOURCE: Spoth, R., Redmond, C., & Shin, C. (2000) Reducing adolescents' aggressive and hostile behaviors: Randomized trial effects of a brief family intervention four years past baseline. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 154, 1248-1257 Barriers to effective prevention policy Short-sighted policy making Concerns with the here and now outweigh future issues Inequitable funding Cost-benefit analysis Assessment of program impact taking costs into account “Evaluation of alternatives according to their costs and benefits when each is measured in monetary terms.” Levin & McEwan (2002) Program economic-benefit indicators: 1. Net economic return is Benefits – Costs 2. Benefit-cost ratio is Benefits / Costs An illustration of cost-benefit analysis: Two children born in similar circumstances Johnny Ricky Both live in similar environments characterized by risk factors such as: Poverty Family history of criminal behavior Family history of maltreatment or neglect Single parent household Low parental education At age 3 Johnny is cared for at home by his older sibling and aunt Ricky is enrolled in the Chicago Child-Parent Center Johnny Ricky The program provides educational enrichment for Ricky Parent education for Ricky’s mother Home visits, health screening, and other services The Chicago Longitudinal Study Study follows a cohort of students who were 3 or 4 years old in Chicago in 1985 Study looks at various combinations of preschool participation (1 year or 2 years), school-age program participation, or no program participation Wide range of outcomes measured: educational success/attainment, criminality, childbearing, etc. Age-21 follow-up interviews: 989 young adults who attended a Child-Parent Center preschool and 550 who did not Overall, the preschool program was found to have benefits of $10.15 for every dollar spent Learning from Johnny and Ricky “Johnny” and “Ricky” are examples of the best- and worst-case outcomes for youth from the study sample for CPC preschool or no CPC preschool We will look at Johnny’s and Ricky’s outcomes at critical points in their development, and the public costs and benefits associated with those outcomes We will also see what percentage of the preschool group and what percentage of the comparison group experienced each outcome, positive or negative Most participants in the study probably experienced a mix of negative and positive outcomes Public costs for Johnny & Ricky in the preschool years $0 Johnny - $5,364 per year for 2 years Ricky NOTE: All dollar amounts are converted to 2006 dollars, based on present-value calculations in 1998 dollars published in Reynolds, Temple, Robertson, & Mann (2002). Age 21 Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Title I Chicago Child-Parent Centers. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 24(4), 267-303. At age 9 Johnny is enrolled in special education classes - $9,497 per year for 4 years (Above and beyond normal instruction costs) Johnny Ricky succeeds at school $0 (Only normal instruction costs) Ricky At age 9 Johnny is enrolled in special education classes Ricky succeeds at school 24.6% of comparison children were enrolled in special education for at least one year, compared to only 14.4% of the preschool participants. Johnny Ricky At age 10 Johnny is found to be the victim of child abuse - $10,861 Ricky’s family has no contact with the child welfare system $0 (Average cost for child welfare services with a substantiated report) Johnny Ricky At age 10 Johnny is found to be the victim of child abuse Ricky’s family has no contact with the child welfare system 10.3% of comparison children were found to be victims of maltreatment between the ages of 4 and 17, compared to only 5% of the preschool participants. Johnny Ricky At age 14 Johnny is arrested - $16,690 Ricky stays out of trouble $0 (Average juvenile justice system expenditure for a court petition) Johnny Ricky At age 14 Johnny is arrested Ricky stays out of trouble 25.1% of comparison children had at least one petition to juvenile court by age 18, compared to only 16.9% of the preschool participants. For violent arrests in particular, the numbers were 15.3% for the comparison group and 9% for the preschool group. Johnny Ricky At age 14 Johnny is arrested Ricky stays out of trouble • For every 100 children served by the program, 17 eventually came into contact with the juvenile justice system. • For every 100 children not served by the program, 25 had at least one petition in juvenile court. • That means eight fewer juvenile offenders - and $133,520 saved in the juvenile justice system alone – for every 100 children served. • This translates to juvenile justice savings of $1,335 for each child served by the preschool program. Johnny Ricky At age 18 Johnny doesn’t graduate from high school and is often unemployed $0 Ricky graduates from high school and enrolls in college - $4,039 per year for 4 years (Average taxpayer share of cost for tuition at a Chicago university) Johnny Ricky At age 18 Johnny doesn’t graduate from high school and is often unemployed Ricky graduates from high school and enrolls in college 61.9% of preschool participants had graduated from high school by age 21, compared to only 51.4% of the comparison group. At age 21, 47% of preschool participants were attending college. Johnny Ricky Entering adulthood Johnny is in and out of jail for petty crimes - $40,195 (Average criminal justice system expenditure over an adult criminal career) Johnny Ricky graduates college and gets a good job + $78,838 (Increased tax revenue based on lifetime earnings of $223,303 greater than a nongraduate) Ricky Entering adulthood Johnny is in and out of jail for petty crimes Ricky graduates college and gets a good job These projections for adult outcomes were based on the age-21 follow-up and national statistics. Researchers continue to track the preschool participants and comparison group and will refine these estimates based on reports of actual outcomes throughout their adult years. Johnny Ricky Other differences in Johnny and Ricky’s adult lives Johnny has poor health Ricky is more likely to be healthy Johnny relies on public systems for living expenses and health care Ricky supports himself and his family, pays taxes, and stays out of trouble Ricky is more likely to be involved in raising his own children Based on findings from the Perry Preschool Age 40 follow-up and projections from the Chicago Child-Parent Study at Age 21 Overall costs and benefits to society Special education - $37,988 Child welfare system - $10,861 Juvenile delinquency - $16,690 Chicago Child-Parent Center - $10,728 College tuition - $16,156 Increased tax revenue + $78,838 Adult crime - $40,195 TOTAL: - $105,734 Johnny TOTAL: + $51,954 Ricky Cost-benefit analysis summary Cost-benefit analysis builds on a rigorous evaluation of program impacts over time The analysis takes into account: Costs of program participation Costs and monetary benefits – for individuals and for society – of various outcomes Percentage of individuals in each group who experience those outcomes Result: Average impact of the program across individuals Some limits of evidence-based programs May not address targeted issues (most are prevention oriented) Often problem-focused May deter grassroots program development Can be costly to implement May not be practically feasible at site May not be well matched to local context Tells you what works but not why May ignore local knowledge, experience & expertise A less orthodox view of evidence-based programs FINDING A BALANCE BETWEEN: Only scientifically proven interventions Centrally designed and certified interventions vs. vs. Interventions based on good intentions or recent fads Interventions reinvented in every new setting Finding the balance: Evidence-based practices & principles Implementing evidence-based programs is not always possible or desirable Community ownership of programs and local, practitioner knowledge of “what works” are also valuable The accumulating evidence from evidencebased programs can be used to improve current practice even when it is not possible to implement a “gold standard” program Principles of effective interventions Program characteristics that are consistent across effective programs Derived from evaluations of evidence-based programs Only rarely studied independently Useful for Improving existing programs Selecting programs Evaluability assessment Funding decisions Principles of effective prevention programs Delivered at a high dosage and intensity Comprehensive Appropriately timed Developmentally appropriate Socio-culturally relevant Implemented by well-trained, effective staff Implemented using varied, active methods Based on strong scientific theory Evaluated regularly Principles of effective juvenile offender programs Provide human services, not just punishment Assign offenders to programs based on risk of recidivism Address criminogenic needs of offenders Be responsive to offenders’ learning styles and readiness to change Implement programs with fidelity to their original design Moving toward evidence-based practices Assess your own program practice against the principles of effective programs General principles for prevention programs or juvenile offender programs More specific principles for your type of program Engage staff and other stakeholders in making improvements based on those principles Seek assistance from evaluation specialists (University, Extension, others) to support continuous program improvement Moving toward evidence-based practice: Discussion How do you see yourself moving toward evidence-based programs or practices in your work? What are the barriers? What kind of support do you need?