Sue Lyle: Narrative, imagination, philosophy and the young child [PPTX 9.95MB]

advertisement

![Sue Lyle: Narrative, imagination, philosophy and the young child [PPTX 9.95MB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/014974106_1-2a1b7e2912db9d3cb753c2e78448a32c-768x994.png)

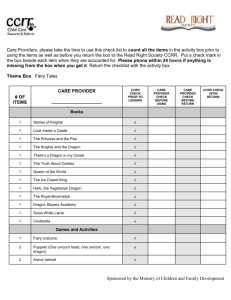

Narrative, Imagination, Philosophy and the young child Dr Sue Lyle Former Head of CPD, Swansea Metropolitan University. Director of: Dialogue Exchange April 18, 2016 Story When did you last tell a story? What are we? We are story-telling creatures To a far greater degree than we are consciously aware, we look at the world in terms of stories all the time. They are the most natural way in which we structure our descriptions of the world around us. We naturally see our own life as a story, as we do those of others... Through the media, we view the pageant of public life as a continuous kaleidoscope of story. Booker, C. (2004;2) The Seven Basic Plots: Why we tell stories. New York: Continuum Narrative Understanding Narrative Understanding is the primary meaning making tool Narrative Understanding rests on the assumption that human beings make sense of experience by imposing story structure on it Narrative is our way of experiencing, acting, living and dealing with time Implications The narrativity principle has important implications for how we plan learning and teaching The curriculum should be conceived as a story to be told, a story to be heard, a story to be created – TEACHING AS STORYTELLING SUMMARY We are story-telling animals We have a basic need for story to organise our experience Children and adults are no different – we all need story Key authors: Bettelheim 1976; Rosen, 1985; Bruner 1990; Egan 1991; Paley, 1991; 2005; Lyle, 1998; Murris, 2016) Key Question What is the most important resource in any classroom, and particularly one with young children? What word was most frequently used by respondents to the Cambridge Primary Review? HOW DO WE CONNECT TO STORIES? Story depends on the imagination Imagine a Panda Your bedroom A dragon breathing fire Imagination is central to all learning Particularly powerful for the young when playing WE HAVE TO FEED CHILDREN’S IMAGINATIONS THROUGH STORY AND PLAY Stories and Learning Stories = thinking. Promote wondering = ‘I wonder’ STORIES SUPPORT CHILDREN’S: Emotional engagement language acquisition articulation emotional intelligence exploration and understanding of concepts knowledge and understanding that is meaningful Who is the child? Our work with children is the product of who we think the child is. Myth busting: Kieran Egan Learning goes from the concrete to Learning goes from the simple to WRONG WRONG Is Peter Rabbit concrete or Children master the complex rules the abstract abstract? How about the small birds who begged Peter to assert himself and escape from the gooseberry net in Mr McGregor’s garden? How about the anxiety felt by Hansel and Gretel? How about children’s grasp of symbols by age 4? the complex of language and social interaction and adults can’t work out how to operate simple machines. Start with what they know and build on that WRONG Children’s minds are full of monsters, talking middle-class rabbits and titanic emotions. Build on the distant and different, the fantasy and imagination. Support from cognitive research: Alison Gopnik THEORY OF MIND (PSYCHOLOGICAL WORLD) Between 15-18 months a child has developed a theory of mind and demonstrates empathy. PHYSICAL WORLD Understands causality COUNTER FACTUALS Understands ‘what if?’ John Wall Even the youngest child under the most difficult of circumstances interprets their own worlds and relations, however much they are also constructed by them… Each of us is and has been shaped by many layers of surrounding persons, communities and histories…. from the moment of birth open to the world and active in creation of herself... Wall, J. (2010) Ethics in the light of childhood. The cognitive & cultural tool of oracy Language shapes the pre- literate child’s learning and thinking through: Story Pattern, rhyme, rhythm Metaphor Abstract binary opposites Fantasy Awe and wonder Drama and role play The story so far Children and adults are active participants in constructing themselves and the world. Children's development is incoherent and discontinuous, rather than orderly and predictable. The child develops like ginger – influenced by intersectionality: gender, class, ethnicity, age, (dis)ability and experience. Children’s emotions and imaginations are powerful. The child accesses the abstract world through fantasy and metaphor. Barriers Influence of prevailing psychological and social perspectives both on child and on ways of knowing. Hegemonic discourses about child and childhood. Government dictats about ‘good practice’ Multiple models of the child today: The developing child – not-yet-adult – needs time to unfold The innocent child – needs protection Criminal/unruly child (evil) – requires control/socialisation Ignorant child (blank slate) – needs to be developed Excluded child – needs protection Disabled child – victim Economic child – preparation for the workforce All deficit models of the child who is less than the adult Philosophical roots: all presuppose the adult/child binary Rousseau – the child will unfold naturally (nativist) Locke – the child needs to be developed (empiricist) Kant – needs to be interacted with in order to become ‘fully human’ (interactionist) Childism Such models of the child feed prejudice against the child and constructs discriminatory practices. Positions the child as citizen- to-be not as citizen. Prevents critique of developmental psychology and socialisation theories that inform current practice in settings and on training courses. Epistemic injustice – Mirander Fricker Childism is a socially structured prejudice that all children are subject to. It renders children susceptible to identity prejudice. It corrupts hearers' judgements of speaker credibility. Credibility deficit leads to lack of respect for the child speaker. The child is wronged specifically in their capacity as a knower – a distinctive epistemic injustice. To be wronged in one’s capacity as a knower is to be wronged in a capacity essential to human value. The Posthuman child: Murris, 2016 Education should not start from ideas about what a child should become (according to adults) but by articulating an interest in the child who is coming into the world. A subject’s coming into the world is always shaped by the actions of others. The space that is created by the adult for the child must allow freedom to appear To give the chance for the child’s own, unique voice to bring something new into the world. Children are people I attribute to the child the same needs I find in myself: for autonomous action, for personal choice, for privacy, for respect from others, for personal exploration, for moments or periods of psychological regression, for nurturance, for meaningful work, for a reasonable level of power…, for leisure, for equal treatment in situations of dispute. Kennedy, 2006, The Well of Being Bringing it together What happens when children are immersed in stories – where their imaginations drive the curriculum they create for themselves? What happens when we support children’s play and meaning-making with philosophy? Philosophy by children with adults where the context of the play, the connections with other human beings and non-human objects endlessly constructs and reconstructs ‘child-storyartefact-movement-talk’ Stanley & Lyle, (2016) (in print Story-Play-Philosophise Let the children decide where to take the story – their role playing, philosophising and storytelling. Create storytelling spaces Construction areas Pop-up role-play – small world and dressing up Creative areas – art, craft, Themed around the story Through play children experience in an embodied way concepts that are recognized as philosophical problems. As children give shape to their selves in the aesthetic space of play where they can explore their moral selves WHAT STORIES? From age 2-7 focus on Fairy tales, myths, fables, traditional stories – told orally as often as possible with as much animation as possible. Picture books. Children’s own stories. Through stories the children experience in an embodied way concepts that are recognized as philosophical problems. Planning a Storytelling Philosophical curriculum 3-7 years Use Story to work with children’s: Imagination Emotional engagement Fantasy play Drama and role play Metaphor Rhythm, rhyme and pattern Stories express emotions struggle fear loneliness anger deprivation love courage friendship determination jealousy persistence kindness triumph cruelty Fairy tales embody abstract concepts through binary opposites • friends / enemies • right / wrong • powerful / weak • fair / unfair • friend / foe • beautiful / ugly • naughty / well behaved truth / lies anger / forgiveness brave / afraid Create opportunities for philosophical play and story telling Children’s play is like “a traveling troupe of medieval players who arrive, set up their theatre, and then begin performing. It is a world that is run more like a theatre is run than like an everyday world”. Sutton-Smith, 1997: 159. Stories stimulate philosophical play Create spaces where the children play within a story setting they have co-created. Seek to make meaning from the children’s conversations and play . Look for the philosophical potentials. Marion the Princess and the Dragon Once upon a time there was a beautiful princess. She lived in a castle and there was a prince and a witch. She came up and hurt the princess. The dragon was friendly the dragon killed the witch. The dragon rescued the princess. The princess went outside and went to the park then back to the castle again. She took her coat and shoes off and put on her PJs and she danced with the prince. The day the dragon came Once, there was a little girl called Ellie and her mother was very nasty. Her dad was called Miskin and her mum was called Donna. They also had a dog that was really smelly and their dog was called Ben. Just then the almighty wind flew about the ground and a dragon came. The dragon was red and had blue spots all over his body. His eyes were glowing and his nose purple. His horns were gigantic and peach and his claws were brown. The little girl screamed but then Becky came to help, she was the little girl’s grandma. Becky jumped up onto the dragon’s face and took the little girl out of his mouth. The dragon said, “aaaaahh!’ and cried. He was only in disguise, he was actually a kind elf who was making a joke and he didn't mean to scare anyone. Becky felt sorry for the dragon and said to him, ‘please don’t cry’. They all became friends and they all lived happily ever after as they lked off to the park. Preschool children use abstract concepts naturally • It’s my turn (fairness) • You’re not my friend any more (friendship) • Not now (time) • No that toy is mine (ownership) • You’re the baddy and I’ll be the goodie (good/bad) • You’re not sharing (sharing) • Don’t scream at me. That’s not what friends do (friendship) • The fairy is here but she’s invisible (proof) • That’s going to be impossible (possibilities) • The dragon is going to get you back (revenge) • Only girls can play this game (gender) Explore concepts & emotions: developing thinking skills Philosophical play creates a multiplicity of possibilities for children’s thinking Q: Can you be friends with a monster? Q: What if the monster had no friends? Would you change your mind? What if it was so small it could fit in your pocket? Q: I wonder what would happen if a monster came to our classroom? Build on fantasy Would you rather… Have a magic wand Or, A magic carpet? Reception Listening to children Be attentive to the children, their stories and their needs Find diverse ways to let the children's stories be created and told Respect the stories that children create, build on them, develop them Think and talk about stories to explore abstract concepts. Their stories and our response to them is an important part of safeguarding the rights of children. Implications for ITE Students need to examine their beliefs about child Examine key concepts and the emotions associated with adults/children, eg freedom, control, power, social status, Ask: who is worth listening to from an epistemic perspective? Philosophical play needs an experienced listening ear from adults that can connect with the imagination. Conclusion If the teacher has an equity-focus and seeks children's questions, their conjectures and beliefs and can help the children clarify their thinking, exchange ideas and subject them to enquiry, then the child has the opportunity to become who they are.