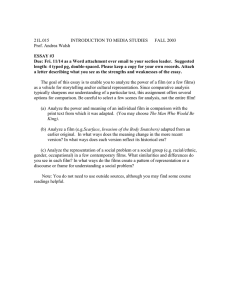

FILM 4200 Fall 2005

advertisement

Kennesaw State University Department of English Minor in Film Studies Dr. David King Office: English Building 271 Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays 1:00 – 3:00 and other times by appointment 770-499-3220 dking2@kennesaw.edu SYLLABUS FILM 4200: Advanced Studies in Film Fall Semester 2005 Monday 6:30-9:15 p.m. Wilson Building 103 Topic for this semester: Rebels with a Cause: Social Realism, Genre Revision, and Individualism in Films of the 1950s COURSE DESCRIPTION (From the Kennesaw State University Catalog effective Fall 2004) FILM 4200—Advanced Studies in Film—(Prerequisites: FILM 3200 or FILM 3220, or permission of instructor) is an intensive study of selected topics in American and international cinema, emphasizing critical theory and analysis of films and related readings. COURSE DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES FOR THIS SEMESTER Two films by Billy Wilder bookend the selections for this course that revisits what many critics now believe was the most important decade in the history of cinema. This course surveys an exciting period when American creativity and ingenuity reacted to changes in society and Hollywood, and explores as well the beginnings of the European art film renaissance. Though the course requires close readings of all the films we will watch and discuss in class, it also encourages you to better understand art within cultural and social contexts. Films for consideration include: Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, Kazan’s On the Waterfront, Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Zinnemann’s High Noon, Ford’s The Searchers, Sirk’s Written on the Wind, Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, Mackendrick’s The Sweet Smell of Success, Fellini’s La Strada, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, and Wilder’s The Apartment. COURSE REQUIREMENTS AND GRADING SCALE Though I will occasionally assign readings that I will provide, the essential texts for this course are the films, most of which we will watch and discuss in class. Each week, I will give you questions, or an essay, to consider about each film. These questions and readings do not limit the scope of our discussion, but they do provide a good beginning for an active and engaged viewing of each film. Watching movies is not a passive exercise; neither should their discussion be uninformed by lack of contextual understanding, nor should the viewing of films usually be a solitary activity. Many 1950s directors were very interested in the notion of audience, and as a student in this class, remember that you are part of our collective audience. That said, however, there may be times that I ask you to view a film on your own at home, particularly if I have interesting secondary materials about the film that I want to show you in class. For this reason, you may want to have an account with Netflix or a similar provider, or you may want to purchase films for yourself. Most of the films on the syllabus are widely available and not expensive. 1. *A take-home midterm exam—20% 2. *A comparative literature/film assignment OR a detailed essay including a decoupage, or shot analysis—40% 3. *An oral introduction to a 1950s filmmaker presented to the class and general class participation—20% 4. *A final essay exam—20% I use a traditional grading scale: A = 100-90 B = 89-80 C = 79-70 D = 69-60 F = below 60 *Exams The midterm exam is a take-home assignment, so that we don’t lose a valuable class day. The final essay is completed during the assigned final exam period. Both exams are primarily subjective; that is, I am interested in your own thoughts, ideas, and opinions. But your subjectivity must be informed by the text, class notes, and class discussion. *Detailed Research Essay/Decoupage This assignment represents the majority of your grade and asks you to assimilate all you have learned about a particular film’s themes and style. Choose one scene, not more than five minutes in length, and analyze the scene shot by shot. The paper should incorporate secondary sources, but the principal ideas should be primarily your own. While the essay considers the film as a whole, the primary exercise here is to show how one representative scene contributes to the overall film. The text of your essay should refer the reader to appropriate stills included in an appendix. Film stills are available from a variety of sources; searching for them will further broaden your knowledge of printed and electronic film resources. Drawings will suffice if they are clearly rendered, but most of you should be able to scan images from DVDs. Your essay must demonstrate that you can analyze all the visual and spatial elements of the film frame including mise en scene, camera angles, shots, and location of cuts; obviously you are considering the “script” and the soundtrack, as well as the film’s narrative or organizational structure, but you must be able to demonstrate an equal understanding of the film’s visual form and style. I will give you more detailed guidelines about this assignment at the middle of the semester. *Comparative Literature/Film Assignment (chosen instead of decoupage) The 1950s were a time of innovation in all of the arts, not just film. In painting, in theatre, in Jazz and classical music, even in the beginnings of rock and roll, artists were continually revising approaches to form, genre, and theory. As many of you are aware, the 1950s were also a remarkable period in American literature. In the modern novel, especially, authors experimented with departures from conventional narrative and pointof-view, and many books from the period reflect the same sort of structural revision apparent in many films of the decade. Thematically, many of these novels were also concerned with the anti-hero and have at their center strong anti-establishment, antiauthority conflicts. The writers of the Beat movement; new young novelists such as J.D. Salinger, John Knowles, and William Styron; and prolific authors such as John Cheever, John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Bernard Malamud were publishing novels that—like their cinematic counterparts—challenged readers to accept new and often subversive approaches to conventional forms. Some students may choose to write a paper on a modern novel that demonstrates its similarity to prevalent themes, characters, and subject matter in 1950s cinema. The authors I’ve named above will give you some ideas, but you are free to choose whatever novel you like, as long as it was published in the 1950s. You may compare the novel to one film, or you may choose to demonstrate how elements of the novel are apparent in several films. *Oral Introduction to a 1950s Filmmaker and Class Participation Each student in the class will introduce to the rest of the class a key filmmaker of the 1950s. All of the directors whose films are being shown and discussed in class will be introduced, but we will also hear about some directors whose work is not being seen in class. Each class meeting, near the beginning of the class, the student or students presenting that evening will give a brief oral introduction to the filmmaker that includes relevant biographical information and discusses key characteristics of the director’s style and themes. Each student must supply a printed filmography of at least five films by the director, as well as a bibliography that lists at least two standard reference works. Students who are so inclined may choose to also show a brief film clip that demonstrates some unique aspect of the director’s technique. Presentations should not be more than about ten minutes in length. On the first night of class, students will sign up for presentations. Finally, a word about participation: the advanced film course is typically small and its success depends upon group discussion and interaction. Make every effort to attend all classes; certainly don’t miss more than one. While I have always been hesitant to implement formal attendance policies, you should be aware that excessive absences will hinder your chances of success in the course. COURSE CALENDAR WEEK 1 – 22 August Introduction to the course, and discussion of 1950s cinema in the context of film history. In particular, we will discuss the social context of the decade and the dramatic changes that took place in the American film industry. Students sign up for filmmaker presentations. Documentary: Hollywood on Trial. WEEK 2 – 29 August Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend and Hollywood Social Realism. WEEK 3 – 5 September LABOR DAY NO CLASS WEEK 4 – 12 September Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront and Social Realism continued. Essay on the film by Edward Murray. WEEK 5 – 19 September Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and subversive genre revision. WEEK 6 – 26 September Alfred Hitchock, Hollywood auteur. Watch Rear Window. WEEK 7 – 3 October Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon and the beginnings of the New Western. WEEK 8 – 10 October John Ford’s The Searchers and the New Western continued. Watch documentary on Ford. TAKE-HOME MIDTERM EXAM DUE. LAST DAY TO WITHDRAW WITHOUT ACADEMIC PENALTY IS FRIDAY 14 OCTOBER. WEEK 9 – 17 October Douglas Sirk and the Hollywood Melodrama. Watch Written on the Wind. Essay on Sirk by Tag Gallagher. WEEK 10 – 24 October Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause. James Dean and the film star as American icon. WEEK 11 – 31 October Alexander Mackendrick’s The Sweet Smell of Success and a discussion of British Social Realism. WEEK 12 – 7 November This week, we shift our attention to the European Art Film Renaissance, a period of international innovation that grew from a number of distinct nationalist cinemas and a variety of aesthetic and philosophical influences. We begin with Federico Fellini’s La Strada, chosen like the subsequent foreign films we’ll consider, because of its impact in the United States. Essay on the film by Edward Murray. WEEK 13 – 14 November Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The European influence upon the Hollywood Renaissance of the 1960s. WEEK 14 – 21 November The American influence upon European filmmakers. The French New Wave. Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. Essay on the film by Edward Murray. WEEK 15 – 28 November Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, and a look toward the New American Cinema of the 1960s. WEEK 16 – 5 December Last night of class. Papers due, except for students who have requested extensions. FINAL EXAM: MONDAY 12 DECEMBER 6:30-8:30 p.m. WB 103 Classroom Policies and Statement of Academic Honesty 1. Turn off all cell phones and pagers before entering the classroom. 2. Food is not allowed in class; water, coffee, cokes, etc. are acceptable, but not in a computer lab. 3. Be attentive during class discussions; exhibit respect for the person who is talking, and raise your hand to be recognized. A college course should be enjoyable, but this does not excuse you from either civility or common courtesy. 4. Make-up work and late work are only permitted at my discretion, and only allowed if you have consulted with me in advance. Dr. King’s Attendance Policy: As a college student, you are privileged to enjoy new freedoms and responsibilities. The decision to attend class should be your choice. However, you should remember these important points: If you miss a class, you are responsible for gathering all notes, activities, and assignments. Because class participation is an implicit part of your course grade, students who miss several class meetings cannot expect to earn a good participation grade. If you have a legitimate excuse for missing class—illness, family emergency, accident—let me know. If you miss class because you are asleep or otherwise incapacitated, accept the consequences. As a general guideline, I recommend that you miss no more than two class meetings for any course you take as a college student. If you must be late to class, or if you must leave class early, please let me know in advance. ACADEMIC HONESTY STATEMENT: Every KSU student is responsible for upholding the provisions of the Student Code of Conduct, as published in the Undergraduate and Graduate Catalogs. Section II of the Student Code of Conduct addresses the University’s policy on academic honesty, including provisions regarding plagiarism and cheating, unauthorized access to University materials, misrepresentation/falsification of University records or academic work, malicious removal, retention, or destruction of library materials, malicious/intentional misuse of computer facilities and/or services, and misuse of student identification cards. Incidents of alleged academic misconduct will be handled through the established procedures of the University Judiciary Program, which includes either an “informal” resolution by a faculty member, resulting in a grade adjustment, or a formal hearing procedure, which may subject a student to the Code of Conduct’s minimum one semester suspension requirement.