Training Resources on Security Sector Reform Assessment, Monitoring and Evaluation and Gender

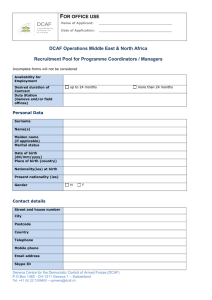

advertisement