Training Resources on Security Sector Reform and Gender Gender and Security Sector Reform

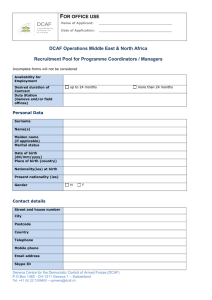

advertisement