Training Resources on Defence Reform and Gender Gender and Security Sector Reform

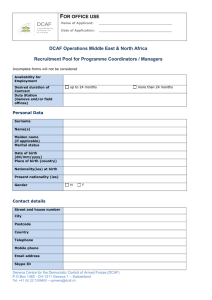

advertisement