CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

advertisement

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

MULE DEER HABITAT REQUIREMENTS

AND THEIR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

FOR CHEESEBORO CANYON

A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in

Geography

by

Janet M. Edwards

May 1987

The thesis of Janet M. Edwards is approved:

Dr. Robert Hoffpa\1\it\

Dr. Phillip Kane, Chair

California State University, Northridge

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several

individuals assisted me with the thesis.

Superintendent John Reynolds,

Park,

North Cascades National

suggested mule deer as the subject for the thesis.

Robert Plantrich, forester for the Santa Monica Mountains

National Recreation Area,

graphs,

fire

assisted with aerial photo-

the vegetation map,

management

Plantrich,

deer observation data and

information.

Paul Rose,

David Ochsner,

Robert

and Timothy Thomas, all members of

the park's Resource Management Division,

reviewed the

draft thesis and provided useful comments;

Tim Thomas

critiqued the draft as thoroughly as a committee member.

Assistant Superintendent Nancy Ehorn provided critical

information

on

the

practices.

Dr.

park's

management policies

Gerald \vright,

National

and

Park Service

biologist, Cooperative Parks Study Unit at the University

of

Idaho,

offered

Kheryn Klubnikin,

insights

into the

original draft.

formerly environmental specialist at

the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area,

also commented on the scope of the project.

I

Mount

am grateful to Jerry Sanders,

former dispatcher,

Rainier

his

National

Park,

iii

for

support

and

encouragement throughout the tedious hours of typing the

first

draft.

I

also wish to thank Robert Ortman for

proofreading the draft and providing numerous

insights

and Nikki Nachun for typing the final editions.

Special thanks are extended to my committee members,

Dr. Phillip Kane,

Logan.

Dr. Robert Hoffpauir,

and Dr. Richard

Dr. Kane not only commented on the written work,

but provided a valuable critique of the project while in

the field.

Dr. Logan critiqued the written drafts,

in a

manner

thorough

I

as

as

that

of

a

thesis

chair.

am

particularly grateful to these professors as well as

California State University graduate advisors

in the

Geography Department, Dr. Gordon Lethwaite and Dr. Robert

Gohstand,

for

their

support

to students who conduct

graduate work in conjunction with a full-time profession.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

iii

LIST OF TABLES . • • . • . . . • . • • • • . • • . . • . . . . . • • • • . . . . . . . • . viii

LIST OF FIGURES.... . • . • . . . . . • . • . • • • . . . . • • . .. . . . . . . • . .

ix

ABSTRACT • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

X

FRONTISPIECE ••••••••••.•.•••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••

xii

CHAPTER

I.

II.

INTRODUCTION •••• .•••••.••••.•••••••••••••••••••

1

Purpose of Study.

1

Study Area............... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

Scope of Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF CHEESEBORO CANYON

7

Climate and Hydrology.

7

Geology and Soils ••••••••••••.•••••.••.••••••.. 11

III.

Flora .••

15

Fa una . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22,

Wildfires •.••

23

HABITAT REQUIREMENTS OF MULE DEER IN

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA •••••••••••••••

27

Nutrition.....................................

27

Variation and Utilization of Forage and

Water •.•••.•••••••••.••••••••.••••••••.•

v

29

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

III.

HABITAT REQUIREMENTS OF MULE DEER IN

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (continued)

Forage ............................................ 29

Water . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Home Range. • .. • • • • • . • • • • • .. • .. . • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • . • 41

Trails and Deer Movements ••.•••.•••.••.••.•.•.. 43

Cover. . . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

IV.

THREATS TO HABITAT PRESERVATION IN

CHEESEBORO CANYON. • • • . • • • • • • • . • . • • • . • . • . • • • • • . • 48

Livestock Grazing ••.•••••••••••••••.••••••••.•• 48

Urban Encroachment ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 54

Visitor Usage.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

V.

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS FOR

CHEESEBORO CANYON.... • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • 65

Current Resource Management Policies and

Practices........ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Management Policies ••.•••.•••.•••••••••••••• 65

Park Legislation ••..•.•.•.•••.•••••••••••••. 66

Land Protection Plan ••••••••••••••••••••.•••

C'7

VI

General Management Plan •••••••••••.•.•••••.• 68

Natural Resource Management Plan ••..••••••.• 70

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation

Area Activities Which Affect Mule Deer ••••.•••• 74

Administration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

Resource Management and Scientific

Research... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Visitor Usage.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

Enforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

V.

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS FOR

CHEESEBORO CANYON (continued)

Response to Urban Encroachment •••.••••••.••• 87

VI.

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

90

REFERENCES CITED. • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

94

vii

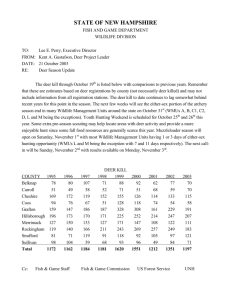

LIST OF TABLES

1.

Canoga Park Monthly Temperature Normals

(1951-1980)......................................

8

2.

Mean Precipitation (1951-1980)..................

9

3.

Percentage of Crude Protein in Forage •••••••••.•

31

4.

Importance of Forage Species By Season •••..•••.•

32

5.

Stomach Analysis in a South Coast Deer

Range. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.

34

Trace Food Items on a South Coast Deer

Range.............................................

35

7.

Inferred Forage Plants of Cheeseboro Canyon....

36

8.

Management Policies and Practices Which Help

or Hinder Mule Deer Resource Protection ••.••••••

75

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

1.

Geographic Range Of Mule Deer................

2

2.

Mule Deer Subspecies in California...........

3

3.

Study Area Vicinity Map ••.....•••.•••.•. Rear pocket

4.

Place Names of Cheeseboro Canyon ....•••. Rear pocket

5.

Sandstone Outcrops of the Chatsworth

For1na t

ion................... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .

13

6.

Vegetation Map ....•.•.......••....••••.. Rear pocket

7.

Chamise, Scrub Oak, and Laurel Sumac.........

17

8.

Middle Canyon After the 1982 Dayton

Canyon Fire..................................

25

The Riparian Zone............................

44

9.

10.

Deer Use of Cheeseboro Canyon .•.......•• Rear pocket

11.

Cattle Grazing...............................

51

12.

Urban Pockets................................

55

13.

Calabasas Landfill...........................

57

14.

Entrance Sign to Cheeseboro Canyon...........

60

15.

Preservation of Mule Deer....................

93

ix

ABSTRACT

MULE DEER HABITAT REQUIREMENTS

AND THEIR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

FOR CHEESEBORO CANYON

by

Janet M. Edwards

Master of Arts in Geography

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area,

is mandated to preserve natural

domain.

One

of

the

California mule deer.

park's

resources within its

wildlife

resources

is

Among their most important habitat

requirements are forage,

cover,

and water.

These basic

elements are found within Cheeseboro Canyon.

Threats

to mule deer habitat in Cheeseboro Canyon

include livestock grazing which alters species composition

and

decreases

the

amount of

forage

and

cover.

Second, urban development, near the south, east and west

boundaries,

Third,

doubled

reduces

the amount of contiguous habitat.

the number of visitors to Cheeseboro Canyon has

in the past year and is expected to jncrease

X

steadily over the next decade.

Heavy visitor usage can

interfere with deers' use of range.

National

Park

Service

actions

which assist

in

habitat preservation include annual prescription burning,

elimination of livestock grazing,

and review of develop-

ment proposals which may adversely affect mule deer.

Habitat

preservation

is

inhibited by

insufficient

information about Cheeseboro's deer population as well as

the quality and quantity of forage.

for

natural

amount of

Insufficient funding

resource management programs restricts the

research and monitoring which can be accomp-

lished.

Using

available

operating

funds,

however,

National Park Service can still protect resources.

the

Those

actions include identification of all mule deer research

needs,

habitat

development of a

requirements,

visitor education program on

assessment

of visitor

impact on

habitat, and implementation of a private land stewardship

program for protecting habitat.

xi

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Purpose of Study

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area

was set aside by Congress in 1978 to protect the natural

resources within this chaparral ecosystem and to provide

opportunities for visitors

that

to enjoy them.

the Santa Monica Mountains range

example

of

island biogeography due

development of nearby properties.

to

It appears

is becoming an

the

constant

Gradually the Santa

Monica Mountains are being isolated from the adjoining

Transverse Ranges because of this development

and Plantrich,

1984,

p.

3}.

(Ochsner

This isolation decreases

plant and animal numbers and diversity which eventually

will lead to loss of species.

One of the wildlife resources within the Recreation

Area which

is

threatened by decreasing open space is

California mule deer

(Odocoileus hemionus californica}.

This subspecies in western North America ranges from the

central foothills of California's Sierra Nevada to the

south coast ranges

(Figures 1 and 2}.

1

2

Figure 1. Geographic range of mule deer.

(1) Rocky Mountain, (2) Desert or burro, (3) California

(4) Southern, (5) Peninsula, (6) Columbian black-tailed

deer, and (7) Sitka black-tailed deer.

Adapted from: Wallmo, 1981, p.3.

3

LEGEND

ROCKY

~

•

Figure 2.

CALIFORNIA MULE DEER

SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS

NATIONAL RECREATION AREA

Mule deer subspecies in California.

Adapted from:

1976, p.S.

California Department of Fish and Game,

4

The purpose of

this study is

to examine National

Park Service policies and practices relating to mule deer

preservation

and

to determine

whether

all necessary

actions are being taken to preserve this wildlife species

in Cheeseboro Canyon,

one of the park sites within the

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

The

physical geography and habitat characteristics of this

site are reviewed to determine if the basic mule deer

habitat elements exist.

In order to verify this,

an

examination of mule deer habitat requirements in Southern

California has been undertaken.

Threats to mule deer in

this park unit are discussed to demonstrate the need for

examination of National Park Service resource management

polices and practices.

one

wildlife

species

Although this study focuses on

in one park

site,

it

also has

resource management implications for the preservation of

other wildlife species within the canyon and in other

areas of the Recreation Area.

Study Area

The Cheeseboro Canyon study site,

at the northern-

most point of the Recreation Area, is located in the Simi

Hills Transverse Mountain Range. Bell Canyon and the San

Fernando Valley 1 i e

to the east and Thousand Oaks and

Agoura to the west (Figure 3, rear pocket). Cheeseboro is

approximately

14 miles

north

of

the

coast

and

is

5

separated from the Santa Monica Mountains by the Ventura

Freeway.

Cheeseboro CanyGn was acquired primarily for

wildlife

Service

resources.

in

1981,

it

Purchased by the

serves

as

a

its

National Park

wildland connection

between the Santa Monica Mountains and the Simi Hills,

Santa Susanna Mountains and mountain ranges

in Santa

Barbara and San Bernadino Counties. The need to retain

Cheeseboro as a

wildlife corridor is critical for the

long-term survival of wildlife, especially larger mammals

such as mule deer (Ochsner and Plantrich, 1984, p. 4).

Cheeseboro Canyon has been chosen as the study site

because

its

abundant

wildlife

resources

are being

increasingly threatened from internal activities such as

visitor usage and external activities,

expansion,

development

on

nearby non-park

such as urban

properties.

Urban

is continually encroaching upon the open

landscape causing Cheeseboro Canyon to become an island

within an island.

Scope of Study

After describing the physical setting in Chapter 2,

Chapter 3 identifies the essential.habitat requirements

for

mule

California.

and horne

deer

in

chaparral

ecosystems

of Southern

The description of necessary forage, cover,

range have been

extracted

from published

6

literature.

Field reconnaissance provided specific

information on the habitat within Cheeseboro Canyon.

Three threats to habitat preservation in Cheeseboro

are

identified and discussed in Chapter 4.

grazing, urban development,

Livestock

and visitor use all have the

potential to adversely impact natural habitat and are

present within the National Recreation Area boundary.

The National Park Service natural resource management polices and practices applying to the Recreation

Area are evaluated in Chapter 5 and 6 according to their

effect

Finally,

on preservation

actions

of

deer

taken by the

and

their habitat.

agency

to monitor and

address threats are also considered.

Sections of the study area will be described using

place names (Figure 4, rear pocket) devised by the author

and most are not officially recognized. They are listed

to clarify the locations of specific canyons and ridges.

CHAPTER II

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF CHEESEBORO CANYON

Climate and Hydrology

Cheeseboro Canyon ranges in elevation from 1300 feet

above mean sea level in the riparian zone,

along the northwest boundary.

mild,

to 2300 feet

The regional Mediterranean

climate

of

rainy winters and hot dry summers

prevails

in Cheeseboro Canyon.

Annual daytime tempera-

tures range between 50 degrees and 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

Average annual precipitation ranges from 16 to 25 inches.

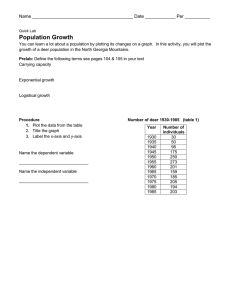

Tables 1 and 2 provide monthly data on temperature and

p r e c i p i t a t i on

f r om

three

Canoga Park Pierce College,

Topanga Patrol Station

stat ions

near

Cheese b oro :

Lechuza Point Station,

(Figure 3,

rear pocket).

and

Also

nearby, the Rocketdyne Test Laboratory at an elevation of

1,550

feet

recorded 62.6 degrees

monthly mean

precipitation.

temperature

with

41

Fahrenheit as

the

inches of annual

In 1984 the test laboratory recorded 65

degrees Fahrenheit as a monthly mean temperature and 11.1

inches of precipitation.

Rainfall dropped again in 1985

7

8

TABLE 1

CANOGA PARK MONTHLY TEMPERATURE NORMALS {1951-1980)

STATION:

ELEVATION:

Canoga Park

Pierce College

790 ft.

MONTH

MAX

MIN

MEAN

January

67.0

39.1

53.1

February

69.9

40.4

55.2

March

71.5

41.3

56.4

April

75.7

44.1

59.9

May

79.7

48.6

64.2

June

86.4

52.6

69.5

July

94.9

57.0

76.0

August

94.0

57.5

75.8

September

91.3

54.4

72.9

October

83.6

48.7

66.2

November

74.4

42.6

58.5

December

68.6

39.1

53.9

79.8

47.1

63.5

ANNUAL AVERAGE

IN INCHES:

Source: Court, 1985, p. 16.

9

TABLE 2

MEAN PRECIPITATION (1951-1980)

Canoga Park

Pierce College

Lechuza Point

Station

ELEVATION:

790 ft.

1600 ft.

January

4.03

5.78

6.78

February

3.26

4.35

5.02

March

2.46

3.12

3.76

April

1.19

1.72

1.85

May

.25

.30

.28

June

.02

.06

.02

July

.00

.01

.02

August

.15

.09

.14

September

.16

.27

.22

October

• 25

.27

.27

November

2.13

2.98

2.99

December

2.10

3.17

3.44

16.00

22.12

24.59

STATION:

ANNUAL TOTALS

IN INCHES:

Source:

Court, 1985, p. 40, 42, 46.

Topanga

Patrol

Station

745 ft.

10

to 10.6 inches and a

monthly mean temperature of 63.4

degrees Fahrenheit (Rocketdyne, 1983-1985).

Cheeseboro Canyon creek is an intermittent tributary

in the Medea Creek watershed, which is the largest within

the National Recreation Area.

Although the

u.s.

Geologi-

cal Survey has established stream flow gauges for some of

the

streams

in the Santa Monica Mountains,

taken for Cheeseboro Canyon.

runoff

feeds

streambed is

no data are

Normally in winter,

the stream channel.

During

storm

summer

the

usually dry and may remain so until late

spring

if winter precipitation has been low.

Besides

runoff,

the stream is fed by four natural springs on the

property, Lower Spring, Sulphur Spring, Upland Spring and

Northwest Spring.

During

field observations after the winter rains,

three to twelve inches of water filled Cheeseboro Creek

south of the springs.

rainy season.

Water was prevalent throughout the

By Apri 1, springs produced less water

and streambeds began to dry.

springs was a

By August,

water at the

few inches deep, but was present for only

several hundred feet downstream from the springs.

pattern of

abundant

water

in winter

This

and scarcity in

summer was characteristic during field studies from 1983

to 1985.

Although no water quality data are available on

springs within Cheeseboro Canyon,

information on springs

11

within Los Angeles and Ventura Counties provides insight

into similar springs.

found

at

rates

range

elevations .from 280 to 5240 feet.

components

from 3 to 61 gallons per

include sodium sulfates,

bicarbonate

sulfate,

bicarbonate

sulfate,

calcium sulfate.

to

Within these counties springs are

sulphur

in

Discharge

minute.

calcium,

Chemical

magnesium,

calcium bicarbonate,

sodium chloride,

and

calcium

magnesium

The springs have a milky appearance due

suspension.

Data

collected on springs

within five miles of Cheeseboro indicated that the water

is

soft

sulphur

lack

and

odor

of

good

(Mendenhall,

of data on

1913,

quality

p.

wildlife,

in the riparian

with

253).

the quality of water

its suitability for

water

drinking

a

strong

Despite the

in Cheeseboro and

deer were often seen near

zone and tracks

are

found

to the

water's edge.

The

Chatsworth

Canyon is eroded,

sandstone,

p. 89).

Format ion,

into

which Cheeseboro

is a thick sequence of upper Cretaceous

mudstone,

and

Cheeseboro Canyon

conglomerate

consists

of

(Carey,

1981,

thin

thick

to

bedded sandstone which is fine to coarse grained.

Shale

and siltstone can also be found but are rare (Schymiczek,

1981,

p. 19).

The Chatsworth Formation

is part of a

large submarine fan complex involving beds of equivalent

12

age and facies

in the Simi Hills and the Santa Monica

Mountains to the south (Link, 1981, p. 7).

Cheeseboro Canyon is carved into the southern face

of the Simi Hills.

for

Its upper portion trends southeast

approximately one

another mile.

mile and

then

The width of the valley floor varies from

approximately 200 feet

in the narrow portions of South

Cheeseboro to approximately 1000 feet

Slopes vary

turns south for

from gentle

inclines

in Northwest Bowl.

in South and Lower

Cheeseboro to steeper canyon walls at the Northwest Bowl

and at Browse Bend.

Rock outcrops are visible at Quail Uplands,

Rocky

Creek Bend and on the east-west ridge overlooking Coyote

Road.

A major rock outcrop is visible at Baleen Rock in

the Middle Canyon.

Outcrops can also be seen at Quai 1

Uplands (Figure 5).

In

it s

sinuosity.

up p e r

pa r t ,

the

rna in stream has

1i t t 1e

In Lower Cheeseboro the stream meanders more

noticeably~

Several

short

side canyons

drain

into

Cheeseboro Creek, primarily in the southeast section of

the study area.

The main creek bed is generally two to five feet

deep,

the

shallower

deep e r

in the south section of the canyon than

Nor t h we s t

Bow 1 .

approximately three to eight feet.

The wi d t h

ranges

f rom

14

So i 1 s

in

the Simi Hi 11 s

are

characteristically

shallow, poorly drained, causing considerable runoff, low

fertility,

low alkalinity,

Park Service,

1982,

p.

soils are dry xeralfs,

and

41.)

low salinity (National

In Cheeseboro Canyon the

with a mean annual temperature

greater than 47 degrees Fahrenheit.

a gray to brown surface.

These alfisols have

The subsurface horizons have a

medium to high base of clay.

Two rna jor so i 1 types are found in Cheeseboro.

the north and

middle

section of

the canyon,

In

Gaviota

association soils have developed on canyonwide sedimentary rock.

These Gaviota association soils are found on

15 percent to 30 percent slopes to steeper hillsides of

30 percent to 50 percent and are well-drained sandy loams

that

are

shallow

underneath,

(8-14

inches)

with a pH of 7.

is moderate to rapid.

sandstone

Vegetation on these soils

generally consists of brush,

(So i 1 Conservation Service,

and cover

annual grasses,

1970, p.

27) •

and oaks

Permeability

Surface runoff is medium to rapid

with moderate to severe erosion.

Soil types of the Calleguas-Arnold association can

be

found

in

the

Cheeseboro Canyon.

middle

and

southern

sections

of

They are characteristic of mountain-

ous uplands of 10 percent to 50 percent slope.

They are

well-drained shaly loams that are shallow over shale or

sandstone and are somewhat excessively drained sands that

15

are very deep over sandstone (Soil Conservation Service,

1970,

p. 15).

brush,

Service,

The associated vegetation consists of

annual

grasses,

1970, p. 15).

and

forbs

(Soil Conservation

Low fertility is characteristic

for both soils which are susceptible to sheet erosion.

Steep slopes

drained,

(those over 50 percent) are excessively

shallow,

soil profile.

and coarse with rocks and gravel

in

They have an angular, blocky structure and

neutral pH at the surface.

Flora

Vegetation in Cheeseboro Canyon is a combination of

mixed chaparral,

grasslands.

coastal sage scrub,

oak woodland,

and

Chaparral grows in shallow, coarse soils and

consists of sclerophyllous

(drought

tolerant) plants,

generally woody shrubs with thin dry leaves and deep

roots.

The

roots

pat tern wi tl1 a

are

extensive and

form a

lateral

second network of deep roots which seek

water during summer drought.

from three to fifteen

feet

Chaparral generally range

in height,

with an average

height of three to six feet (Hanes, 1977, p. 449).

Most chaparral plants are evergreen with thin leaves

for the purpose of conserving moisture.

within the

Tannin is found

leaves of most species increasing suscepti-

bility to fires, a necessary ingredient in the life cycle

of this fire-climax vegetative association.

16

Cheeseboro Canyon

communities

is

representative of the plant

described by Pearsons

for

Palo Comado.

According to Pearsons,. the mixed chaparral association in

the

Palo Comado-Cheeseboro Canyon

following species:

(Quercus dumosa),

loides),

laurel

large

sumac

sugarbush

(Rhus

laurina),

and monkey flower

(Rhamnus

ilicifolia),

southern honeysuckle

p. 55).

toyon

ilici-

Climbing penstemon

(Heteromeles arbutifolia),

(Mimulus australis)

are also found in

although toyon is uncommon.

stoma fasciculatum)

the

scrub oak

hollyleaf cherry (Prunus

1984,

(Keckiella cordifolia),

Cheeseboro,

(Rhus ovata),

leaved redberry

(Pearsons,

contains

mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betu-

(Lonicera subspicata),

folia)

area

Chamise (Aden-

is often in almost pure stands from

six to nine feet tall on south facing slopes which also

support yerba santa (Eriodictyon crassifolium).

ita

(Arctostaphylos glandulosa),

berberdifolia)

and scrub oak

are found on north-facing slopes

Manzan(Quercus

(Taber,

1958, p. 64) (Figure 6, rear pocket).

Mixed chaparral species occur commonly in Middle

Canyon to Northwest Bowl

scrub oak

(Figure 7).

(Quercus berberdifolia)

Creek Bend sunflower

(Datura meteloides),

Near Loop Flats

is common.

(Encelia californica),

tree tobacco

At Rock

jimson weed

(Nicotiana glauca),

mustard (Brassica spp.) and Indian paintbrush (Castilleja

affinis) are found throughout Middle Canyon.

In the

18

central canyon around Loop Flats,

chamise

(Adenostoma

fasciculatum), black sage (Salvia mellifora), and laurel

sumac

(Rhus laurina)

stump sprouts are prevalent.

Tree

tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) is found on the disturbed site

along the road between Middle Canyon and Quail Uplands.

In the Northwest Bowl,

the most predominant species is

chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum).

in this

yerba

location

santa

Other common species

include scrub oak

(Quercus dumosa),

(Eriodictyon crassifolium)

sage

(Salvia

spp.), and laurel sumac (Rhus laurina).

The coast a 1 sage scrub plant community is common in

the canyon.

It is an open, partly woody shrub community

which quickly invades disturbed soils.

drought

deciduous,

that

is,

some

Some species are

leaves drop off,

retaining moisture in the plant during the hot,

months.

This plant community is noted for

quality,

especially sage and sagebrush.

steep

south

facing

slopes

and

is

summer

its aromatic

It is found on

often below the

chaparral community on actively eroding or

unstable

slopes.

Coastal

sage

scrub grows

in dry,

thin

soils on

gravelly or rocky slopes. The soils are low in fertility

and are subject to rapid erosion.

The primary species

included

coastal

in

(Artemisia

phylla),

this

community

californica),

and black sage

are

purple

sage

sagebrush

(Salvia

(Salvia mellifera).

leuco-

Sagebrush

19

may be dense or scattered with £orbs and grasses intermixed.

This

community also

consists

of

yucca

(Yucca

whipplei), California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum),

bush

sunflower

(Encelia californica),

(Nicotian glauca),

sugarbush (Rhus ovata),

elderberry (Sambucus mexicana)

Golden yarrow

sumac

(Rhus

lepida).

(Pearsons,

tobacco

and Mexican

1984, p. 54).

(Eriophyllum confertifolium) and laurel

laurina)

are

coastal sage communities

p. 54),

tree

as well as

found

in Cheeseboro Canyon

(National Park Service,

small-flowered needle grass

1985,

(Stipa

Coastal sage is especially noticeable in South

and Lower Cheeseboro.

Native grasslands

grasses

and both

in the canyon consist of annual

annual

dominant perennial grass

pulchra).

and

perennial

£orbs.

is purple needlegrass

The

(Stipa

Annual grasses such as wild oat (Avena fatua),

slender wild oat (Avena barbata) and

moll is) are found within the area.

melitensis),

mustards,

soft chess (Bromus

Tocalote ( Centaurea

(Brassica spp.),

yellow sweet

clover (Melilotus indicus),

red stemmed filaree (Erodium

cicutarium),

(Bromus diandrus),

ripgut grass

foxtail

barley (Hordeum leporinum), and red brome (Bromus rubens)

are

the common

p. 52).

Owls'

ann ua 1

clover

forb

species (Pear sons,

(Orthocarpus

1984,

purpurascens),

microseris (Microseris linearifolia) and tidy tips (Layia

20

platglossa) are also annual £orbs found within the canyon

(Pearsons,

1984,

p. 52).

Perennial

forbs

include

Catalina Mariposa lily (Calochortus catalinae), golden

stars

(Bloomer ia crocea) ,

wild hyacinth ( Dicelostemma

pulchella) and harvest brodiaea (Brodiaea jolonensis).

Other

weedy herbs

include horehound

(Marrubium

vulgare), bur clover (Medicago polymorpha), white stemmed

filaree

(Erodium moschatum), California chicory (Rafine-

squia californica),

pastoris),

Shepard's purse

and common sow thistle

(Capsella bursa-

(Sonchusoleraceus)

(Pearsons, 1984, p.53).

Ashy leaf buckwheat

Indian paintbrush

(Eriogonum cinereum),

(Castilleja

affinis),

coastal

saw toothed

goldenbush (Happlopappus squarrosus), and deerweed (Lotus

scoparius),

are also scattered throughout the canyon

(Pearsons, 1984, p. 54).

In disturbed areas,

such as canyon bottoms with

, ..: _,..... ... , .. ,. trafficked dirt roads where cattle have grazed

.l..L':::Jlll-.L:J

for years, non-native species have invaded.

mustard

(Brassica

geniculata),

melitensis), horehound

(Nicotiana glauca),

flora),

tocalote

(Marrubium vulgare),

Short podded

(Centaurea

tree tobacco

telegraph weed (Heterotheca grandi-

California chicory (Rafinesquia californica),

soft chess

(Bromus mollis),

and foxtail chess

rubens) have replaced native species.

(Bromus

21

Coast

(Quercus

live oak

lobata),

californica)

oaks,

(Quercus agrifolia),

valley oak

and California black walnut

dominate the oak woodlands.

the most common trees,

(Juglans

Coast

live

are scattered on the north

facing slopes of both the coastal sage and mixed chaparral communities, particularly in canyon bottoms or north

facing slopes where soils are "deep,

moist,

loamy, or gravelly,

well aerated and well drained" {Pearsons,

1984,

10:.

p. 57).

The understory of

of miner's

lettuce

(Stellaria media),

fiesta

flower

the woodland

is composed

(Claytonia perfoliata),

goose grass

(Pholistoma

chickweed

(Galium aparine), blue

auritum),

common

eucrypta

(Eurypta chrysanthemifolia), Pacific sanicle (Sanicula

crass i c au 1 i s ) ,

purple sage

( Sal v i a

leu coph y ll a ) ,

coastal goldenbush (Haplopappus venetus).

is open,

sunlight will dry the soils.

and

If the canopy

The understory

includes western wild rye (Elymus glaucus) and giant wild

rye

(Elymus

condensatus)

(Pearsons,

1984,

p. 57).

Commonly exotic grasses have replaced understory native

annual grasses in these woodlands (National Park Service,

1985, p. 58).

The riparian area extends throughout the center of

the study area

from Northwest Canyon to Lower Canyon.

The densest riparian vegetation is found in Northwest

Canyon and Enchanting Forest.

agrifolia),

Coast live oak

California sycamore

(Quercus

(Platanus racemosa),

22

western verbena (Verbena lasiostachys), white hedgenettle

(Stachys albens),

mulefat

(Baccharis glutinosa),

glauca),

common,

Douglas nightshade

arroyo willow

red willow

(Salix

(Salix

(Solanum xanti),

tree tobacco (Nicotiana

lasiolepis)

laevigata)

are

and

less

the common

riparian zone species (Pearsons, 1984 p. 58-59).

Fauna

Cheeseboro Canyon serves as habitat for

species of

animals.

californicus),

bonii),

Black-tailed

Audubon cottontail

jackrabbit

several

(Lepus

(Sylvilagus audu-

California ground squirrel (Cite1lus becheyi),

valley pocket gopher,

latrans ochropus),

western fence

(Thomomys bottae), coyote (Canis

bobcat

lizard

(Lynx rufus californicus),

(Sceloporus occicentalis biseri-

atus), side blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana herperis),

southern alligator

lizard

(Gerrhonotus multicarinatus

webbi), gopher snake (Pituophis melanoleucus annectens),

common kingsnake

(Lampropeltis getulus californiae), and

western rattlesnake

(Cortalus viridus helleri)

this chaparral region (Pearsons,

racer

1984, p. 76).

(Masticophis flagellum piceus)

the California vole

inhabit

The red

is rarely seen and

(Microtus Californicus) and deer

mouse (Peromyscans boylii) are more common.

Several species of birds frequent the area including

dove

(Zenaida

kingbirds

sp.),

sparrow

(Tyrannus verticalis,

(Passer

domesticus),

Tyrannus vociferans),

23

and quail (Callipepla californica).

The canyon is known

as

species of

a

prime habitat

for

various

raptors

including golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), coopers hawk

(Accipiter cooperii),

red

tailed hawk

(Buteo

jamai-

censis), American kestrel (Falco sparverius), screech owl

(Otus asio),

horned owl

burrowing owl

(Athene cunicularia), great

(Bubo virginianus),

long eared owl

(Asio

otus), and barn owl (Tyto alba).

Sightings by the present writer or by National Park

Service personnel of all the species listed above have

not been recorded for Cheeseboro Canyon itself.

However,

because they are characteristic of the habitat found in

Cheeseboro, they are included.

Wildfires

Southern California with its cool,

hot,

dry summers,

is prone to fire

wet winters and

in summer and early

fall when the vegetation becomes dry and fuel moisture is

low.

the

Santa Ana winds beginning in fall,

vegetation

and

increase

further dry out

susceptibility to fire.

Fires generally are ignited by lightning, although arson

fires are also common in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Historically, local Chumash Indians burned chaparral

to promote the growth of plants which contributed to

their diet (Plantrich, 1986, p. 19).

Although they were

set primarily in grassland communities along the coast,

the fires may, on occasion, have burned farther into the

24

interior of

the

coastal

Spanish settlement period,

burned regularly

mountain range.

During the

large areas of chaparral were

to. encourage grassland

(Plantrich, 1986, p. 19).

for

grazing

These fires had no permanent

detrimental effects on the chaparral community and when

used

sparingly,

During the 1800s

probably

increased hunting

success.

local ranchers and homesteaders set

fires to improve their rangelands.

Many large fires occurred from 1900 to 1918 and, for

the safety of local residents, the need to suppress them

seemed inevitable.

In 1919 an organized fire department

was established for the Los Angeles County unincorporated

areas and,

fires

until

the advent of prescription burning,

were suppressed whenever possible. Most fires

in

this period were either accidentally or deliberately set

by humans. Eighty-five fires larger than 100 acres, were

recorded from 1925 to 1985 in the Santa Monica Mountains

(Plantrich,

1986,

p.2lj.

The

last

major

Cheeseboro Canyon occurred in October, 1982.

fire

1n

The Dayton

Canyon fire, as it is now called, began in the Simi Hills

north of Cheeseboro and swept quickly to the Pacific

coast (Figure 8).

A rare lightning-caused fire occurred in Cheeseboro

Canyon in May,

1984.

The fire burned approximately 200

acres in South Cheeseboro,

then continued to burn large

sections of adjoining Las Virgenes Canyon before it was

26

subdued.

Prior to this 1984 fire,

the canyon burned in

1949, 1967, and 1970.

Fire suppression is still the goals of county and

city fire departments.

These suppression techniques have

already altered the natural succession and have resulted

in an increase of decadent plants which have low nutritional value for deer.

CHAPTER III

HABITAT REQUIREMENTS OF MULE DEER IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

Nutrition

Deer need between 6000 and 10,000 calories per day

depending on

p.

60).

the

These

Approximately 75

size of

the

animal (Dasmann,

calories

are

largely carbohydrates.

percent

of

the

calories

1964,

consist of

lipids (fats) with the remainder being protein, vitamins,

inorganic elements and water.

A 100 pound deer eats 2.2

to 3.0 air-dry pounds of forage per day or five to seven

pounds of green browse (Dasmann, 1981, p. 35).

In order to process the chaparral forage,

stomach has

omasum,

into

chambers called the rumen,

and abomasum.

the

resting,

four

rumen

it will

a deer's

reticulum,

Deer select food that will pass

without

chewing.

regurgitate

Finer materials will pass

the

When

"cud"

the deer

is

and chew it.

to the reticulum,

then the

omasum and finally the abomasum. Coarse vegetation matter

stays in the rumen and is attacked by bacteria.

The digestive system depends on the interaction of

bacteria and protozoa.

The rumen converts carbohydrates

27

28

into organic acids called fatty acids.

Proteins are

broken down into amino acids, organic acids and ammonia.

The

crude

fiber

content

of

digesting crude protein.

forage

is

important

It also assists

for

in breaking

down soluble carbohydrates.

How palatable

process.

type,

a plant

is

affects

the digestion

The palatability of plants depends on the soil

season,

amount

of

shade,

burning,

and other

environmental factors {Dasmann, 1971, p. 41).

Protein

deer's

is

diet.

the most

It not

important

ingredient of the

only maintains a base level of

health, but also builds strength against stress, disease

and injury {Dasmann, 1964, p. 52).

Since fawns have higher protein requirements than

mature

deer,

fawn

survival

is

generally

limited by

available nutrition and ample quantity of summer forage

{Dasmann, 1981, p. 41).

that

if a doe

Bowyer {1981, p. 18) points out

is undernourished,

its fawn may be born

underweight which would reduce its chances for survival.

If the female does not nurse her fawns they become more

susceptible to parasites and diseases.

Nursing requires

a high quality diet and ample moisture.

Dasmann

{1981,

actively seek out

p. 24)

foods

indicates

that

that are best for

deer

them.

may

Deer

test leaves before eating them by licking the leaves and

holding them in their mouth.

They also smell them before

29

eating and select certain leaves over others.

select ion of

However,

food is not based entirely on nutritional

value, but also on edibility. Poisonous plants, unfamiliar to a deer,

may be tasted once and then avoided with

no ill effects

(Dasmann,

1981, p. 25).

Deer will eat a

variety of plants but mostly their diet consists of only

a

few species because deer

feed on preferred species

whenever possible.

Variation and Utilization of Forage and Water

Forage

California mule deer feed on browse species

plants)

(woody

at certain times of the year and on succulent

herbaceous plants at other times.

The presence of winter

green grass significantly affects the nutrition of deer.

During the growing season,

annual and perennial grasses

have high protein,

and mineral content.

water

broadleaf herbs appear after the grasses,

When

the deer will

graze on them as long as they are succulent.

Grasses and

forbs vary in nutritional value and palatability just as

browse

spring.

species do,

with

the high protein

Grasses and forbs

levels

in

are also eaten by deer in

winter when protein levels are higher than common browse

species.

Protein content in forage species

deer)

(plants eaten by

drops significantly during summer months after

peaking in spring.

Toyon

(Heteromeles arbutifolia)

and

30

hollyleaf cherry (Prunus ilicifolia) produce new growth

Within two to three months after most browse

in June.

species have reached their peak, this new growth provides

protein in drier periods when deer seek foods to nourish

them until

fall

Tables 3 and 4

summer

foods

rains

arrive

indicate the

(Blong,

1956,

p. 14).

importance of spring and

such as chamise

(Adenstoma fasciculatum),

poison oak (Rhus diversiloba), western mountain mahogany

(Heteromeles arbutifolia),

crassifolium).

and yerba santa

In the fall,

rains

(Eriodictyon

leach water soluble

carbohydrates and minerals from dry vegetation and cause

losses in nutritional value. Increased rains may further

deplete forage quality.

In September,

time

in

grow.

the

the deer eat acorns and spend more

riparian woodland area where the oak trees

Acorns are

low in protein and minerals but are

high in fats and starches.

Deer select acorns from the

most productive trees.

The California Department of Fish and Game indicated

that

no

rumen

analysis have been

Cheeseboro Canyon.

available for

County,

deer

However,

done

stomach

from similar areas

documented by Blong

(1956).

on

deer

analyses

in

are

in Los Angeles

Blong's data

collected in the summer of 1955 show that the stomachs

contained hollyleaf cherry

(Prunus

ilicifolia),

oaks

(Quercus spp.), and toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) the

31

. I

TABLE 3

PERCENTAGE OF CRUDE PROTEIN IN FORAGE

SPECIES

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

s

0

N

D

Chamise

6%

8

11

14

14

10

9

6

6

4

7

7

8

9

10

14

15

12

11

7

7

6

9

7

24

23

21

16

10 10

7

4

Scrub oak

Poison oak

coast live oak -

5

ho1lyleaf

cherry

western

mtn mahogany

7

toyon

9

redberry

8

yerba santa

8

7

10

sagebrush

manzanita

6

17

20 16 12

12

12

9

8

8 10

9

1 A

1 1

........

9

8

7

8

7

- 11

7

8

5

6

7

7

7

6

6

14

17

15

9

15

.LU

.L '"r

16

10

12

9

10

17

13

4

23

6

, c.

13

6

NOTE: Each species is most important

are highest.

Source:

10

7

9 11

6

~1en

protein levels

Biswell, 1955, p. 148-149; Dasmann, 1964, p. 42.

32

TABLE 4

IMPORTANCE OF FORAGE SPECIES BY SEASON

SPECIES

WINTER

SPRING

SUMMER

XX

X

April-June

June-Aug

Chamise

(Adenostoma

fasciculatum)

0

Coast live oak

(Quercus

agrifolia)

0

Scrub oak

(Quercus

berberdifolia)

X

X

Jan-Feb

May

Poison oak (Rhus

diversiloba)----

X

Feb

Grasses and Forbs

Toyon

(Heteromeles

arbutifolia)

0

0

FALL

0

XX

Sept-Dec

X

XX

XX

May

X

0

XX

X

0

0

X

X

XX

X

June-Aug

Hollyleaf cherry

0

(Prunus ilicifolia)

X

Mountain mahogany

(Heteromeles

arbutifolia)

X

XX

Redberry

Rhamnus crocea)

0

XX

June-Aug

X

X

Sept

X

Mar-May

NOTE: XX=Very Important

O=Unimportant

X

May

X

June-Aug

X

Sept

X=Moderately Important

Source: Biswell, 1955: Blong, 1956: Dasmann, 1964, 1981:

Taber, 1958: Urness, 1981.

33

predominant

crocea)

foods

eaten along with redberry

(Rhamnus

and mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides).

Tables 5 and 6 summarize Blong' s data and indicate the

importance of

(Prunus

such woody species as hollyleaf cherry

ilicifolia),

toyon

(Photinia arbutifolia),

and

manzanita (Arctostaphylos sp.) and forbs such as miner's

lettuce (Montia sp.).

Comparing

the

list

California chaparral

plant species

of

deer

foods

zones with Pearsons

in Palo Comado,

in

southern

list of all

Table 7 has been devel-

oped. Since Palo Comado is adjacent to Cheeseboro Canyon,

species are assumed to be similar (see page 36).

In some

cases the genus is listed as forage, but the species is

unknown.

It cannot be inferred from Table 7 that species

which exist in Cheeseboro are in fact eaten by deer.

species is

listed,

likely that

however, because

A

it would appears

if it is a browse plant in another part of

Southern California,

it probably is utilized by deer

in

Cheeseboro Canyon as well.

Throughout the year, deer tend to feed in different

portions of their home

range~

however,

they do not eat

forage uniformly, and some areas are browsed more heavily

than others.

If an area has been overbrowsed by deer,

and most of the palatable and nutritious plants eaten,

the productivity of the plant will decrease (Longhurst,

1952, p. 54).

34

TABLE 5

STOMACH ANALYSIS IN A SOUTH COAST DEER RANGE

This is an analysis of 27 deer stomachs collect during

the dry period (August, 1955}.

PERCENT PERCENT

VOLUME OCCURR.

PLANT SPECIES

BROWSES

Prunes ilicifolia

Quercus sp.

Photinia arbutifolia

Rhus arbutifolia

QUercus wislenzenii

Eriogonum fasciculatum

Ceanothus cuneatus

Hollyleaf cherry

unident'd oaks (leaves}

Toyon

Poison oak

Interior live oak

Calif buckwheat

Buckbrush

Tree lichen

Quercus dumosa

scrub oak

Quercus douglasii

blue oak

Rhamnus crocea

redberry

Cercocarpus betuloides western mtn mahogany

Salix sp.

willow

Quercus sp.

unident'd oaks (acorns}

Quercus agrifolia

coast live oak (acorns}

Fraxinus dipetala

foothill ash

nightshade

Solanum douglasii

SUBTOTAL

23.0

12.5

11.5

4.5

4.0

4.0

3.5

3.0

3.0

3.0

2.5

2.0

2.0

1.5

1.5

1.0

1.0

86.0%

40.7

29.6

51.9

44.4

14.8

22.2

25.9

37.0

22.2

11.1

33.3

33.3

22.2

11.1

11.1

11.1

11.1

FORBS

unidentified forbs

Melilotus sp.

sweet clover

Amaranthus retroflexus rough pigweed

mock locust

Amorpha californica

ground-cherry

Physalis sp.

ferns

Polypodiaceae

SUBTOTAL

4.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

.5

12.5%

51.9

18.5

11.1

11.1

3.7

11.1

1.5

63.0

GRASSES

unidentified

SUBTOTAL

Source:

1. 5%

Blong 1956, Table VII.

35

TABLE 6

TRACE FOOD ITEMS ON A SOUTH COAST DEER RANGE

Those species listed below were eaten by 27 deer during

the dry period (August, 1955).

PERCENT FREQUENCY

OF OCCURRENCE

PLANT SPECIES

Eriodyction crassifolium

Artemisia californica

Populus fremontii

Lonicers sp.

BROWSES

coffeeberry

common mistletoe

manzanita

chamise

wild rose

quixote plant

valley oak

(probably deerweed)

unidentified leafage

wooly yerba santa

California sagebrush

cottonwood

honeysuckle

Centaurea sp.

Compositeae

Mantia sp.

Erodium cicutarium

Galium sp.

Lathyrus sp.

Liliaceae sp.

Madia sp.

Medicago hispida

Mentha sp.

Polygonum

Trifolium sp.

FORBS

star thistle

composites

miner's lettuce

red-stem filaree

bed straw

campo pea

lillies

tar weed

bur clover

mint

knot weed

clover

Bromus sp.

Avena fatua

Horedeum sp.

Juncus sp.

GRASSES

brome grass

wild oat

wild barley

rush

Rhamnus californica

Phoradendron villosum

Arctostaphylos sp.

Adenostoma fasciculatum

Rosa sp.

YUCCa whipplei

Quercus lobata

Lotus sp.

Source: Blong, 1956, Table VII

22.2

18.5

11.1

11.1

7.4

7.4

7.4

7.4

7.4

3.7

3.7

3.7

3.7

14.8

14.8

11.1

3.7

':!

.J o

'7I

3.7

3.7

3.7

3.7

3.7

3.7

3.7

7.4

3.7

3.7

3.7

36

TABLE 7

INFERRED FORAGE PLANTS OF CHEESEBORO CANYON

SPECIES

REFERENCE

ANNUAL GRASSES

Blong

Trippensee

Blong

Blong

Trippensee

Trippensee

Lupine

Wild oat

Bur clover

Buckwheat

Filaree

Evening primrose

Sagebrush

Paintbrush

Clover

Yucca

Purple sage

COASTAL SAGE SCRUB

Blong

Rue

Blong

Blong

Blong

CHAPARRAL

Blong

Blong

Hollyleaf cherry

Toyon

Laurel sumac

Chamise

Encelia

Mountain mahogany

Mustard

Scrub oak

Longhurst

Rue

Longhurst

Trippensee

Trippensee

Longhurst

Blong

Yerba santa

OAK WOODLAND

Blong

Blong

Blong

Rue

Blong

Blong

Redberry

Poison oak

Miner's lettuce

Elderberry

Coast live oak

Valley oak

Douglas' nightshade

Mistletoe

Oaks

RIPARIAN WOODLAND

Blong

Blong

RIPARIAN SCRUB

Blong

Wild rose

NOTE:

*

= trace only

PARTS EATEN

blades

*

leaves/flowers

stems/flowers

leaves/stems

*

*

*

berries

field observ.

new shoots

leaves

twigs

acorns/new

shoots

*

*

*

*

*

*

37

A plant's

resistance to browsing varies with the

season and its site.

Many species can tolerate 40 to 60

percent

destruction by browsing

32-34).

Deer usually prune

selectively nibbling.

of

the plant

(Dasmann,

1981,

p.

the plants they browse by

This actually enhances the growth

and keeps

it

from growing out of reach

(Dixon, 1934, p. 316).

The age of the stand affects the nutritional value

Seedlings and new sprouts are particu-

of the browse.

larly high in nutrients.

Mature plants are tolerable but

older plants are undesirable because their nutritional

value is low.

Fires can improve the carrying capacity of an area

by increasing the amount of edible browse. Fires burn off

the chaparral

and

decadent

vegetation.

The

extreme

temperatures of the fire stimulate seed germination and

stump sprouting.

Stump sprouters draw food and water

from unaffected roots

direct

rainfall

for

and

require

After

spring burns,

(lignotubers)

moisture.

sprouts will appear within three to four weeks and will

be in ample supply throughout the summer months.

Much of

the highly nutritious forage produced the

first year after a fire is underutilized because deer do

not have adequate cover (Ashcraft, 1979, p. 186).

second year,

however,

deer

By the

return to burned areas to

forage because the plants are of sufficient quantity to

38

provide suitable forage regardless of the reduced cover.

During these early years after a burn, forage is

high in

nutrients.

In Cleveland National Forest,

experiment

showed protein

percent higher

Dasmann

levels

for burned sites

(1971,

p.

87)

reports

a

in

fuel

forage

(Bell,

that

modification

10 to 15

1974, p.

older

169).

stands

of

chaparral in California yield 13 to 106 pounds per acre

of browse.

After prescription burning an acre can yield

800 to 1800 pounds depending on the season.

brush was managed by fire

Ranges where

tripled the number of deer

(Longhurst, Connolly, 1970, p. 147).

Ovulation rates

conditions,

ranges

with

with

71

deer vary depending on range

the highest

incidents

the best quality

Biswell reports

are

for

forage.

occurring on

For

example,

that ovulation rates on unburned brush

fawns per 100 does.

After wildfire the rates

increase to 115 fawns per 100 does and on ranges managed

through prescription burning,

145 fawns are dropped per

100 does (Biswell, 1961, p. 133).

Water

Forage is not the only nutritional requirement for

deer.

Water

is

an

habitat. The need

equally important element of the

for

water depends

on

temperature,

moisture content and type of forage, evaporation rate and

39

the deer's condition,

weight and activity (Trippensee,

1948, p. 206).

Water availability depends on rainfall,

structures,

density of vegetation,

soil,

rock

fire frequency,

the condition of the range.

If a fire

non-wettable

formed within the soil is

layer which

is

thicker and reduces soil porosity.

less

intense

fires

because more water

water table

can

is too hot,

and

the

More frequent and

increase water availability

is absorbed into the soil and the

(Plantrich,

1986, p. 87).

This can lead to

Burning riparian areas

increased runoff and water loss.

near springs or seeps, where the vegetation, is thick may

also increase water availability by reducing the rate and

amount of transpiration (Dasmann, 1981, p.20).

Daily water requirements for a 100 pound deer are

2.5 quarts

(Ashcraft,

1979, p. 180) and because of this

deer are found within a half mile to one mile from a

water

source

p.38).

the

(Linsdale,

1953,

p.

328~

Bowyer,

1981,

Water requirements are less in the winter when

moisture

content

in

the

forage

is high.

Deer

generally drink once in a 24-hour period, usually in the

evening or at

urinate

less

night

(Lin s d a 1 e ,

frequently

in

19 53 ,

summer

and

p.

328).

fall,

thereby

retaining more water when the vegetation has a

moisture content.

vegetation

Deer

lower

When deer begin eating succulent

in winter and spring,

urination frequency

40

Deer will not decrease the amount of water

increases.

intake at the onset of fall

rains, but will reduce the

amount of water only after the appearance of more succulent vegetation {Linsdale, 1953, p. 332).

Linsdale

{1953,

p.

333)

reports that during the

spring months of March through May deer drink 1 it tle or

no water.

This is due to the amount of water contained

within the succulent vegetation.

Nursing fawns do not

need to drink water until they are several months old.

During summer drought deer look for water in deep

side canyons,

where rocky ledges may contain pools of

water.

indicates that pools are generally found

Taber

throughout most deer habitats {Taber, 1958, p. 24).

At the San Dimas Experimental Forest in southern

California,

Cronemiller

numerous seeps were found

year-long flows

of water.

{1950,

p.

349)

noted

that

in the area which provided

Even by the end of summer,

pools along stream courses were still full.

Cronemiller

estimated that San Dimas supported 12 to 15 deer per

square mile {Cronemiller, 1950, p. 351).

Because the main stream in Cheeseboro Canyon

generally dry

in the summer,

water is extremely limited.

is

the amount of available

Although there may be rocky

ledges that serve as drinking holes for deer, none were

discovered during

Cheeseboro Canyon.

field

reconnaissance

trips

into

The natural springs on site provide

41

water year-round,with a

meager

supply

in

the

summer

months.

Home Range

Mule deer

inhabit plains,

foothills,

of the western United States.

and mountains

In these various terrains

mule deer are adaptable to many types of habitats and

climatic regions,

desert scrub.

including forests,

shrublands,

and

In areas where there are distinct seasons

marked by significant temperature changes deer migrate

between

however,

two home

there

between seasons

ranges.

is

not

In

Southern California,

enough change

to warrant

Migration generally occurs

in

temperature

long-distance migration.

in areas where snowfall is

prevalent.

Home

range

is

an

area

large enough

individual's physiological needs.

portion of the home range that

have year

round territories:

to meet an

A territory is the

is defended.

Some deer

others defend territories

only during certain times of the year.

Once established,

the territory is held for years.

The size of the home range is one mile in diameter

or smaller with boundaries determined by the terrain and

the presence of food,

1953,

water and cover (Linsdale, Tomich,

p. 335: Ashcraft,

and shape may change,

familiar areas.

1979,

p. 184).

but deer are

The range size

likely to stay in

42

If deer are frightened,

they flee their home range

temporarily, returning within a few hours.

retreat

in the direction familiar

The deer will

to that

individual.

Deer have no difficulty running up or down steep canyon

walls.

(This was observed several times in Cheeseboro

Canyon.

found

The steepness of slopes on which trails were

also

attests

to

the

agility of

mule

deer.)

Irregular topography actually benefit deer because the

slopes conceal them.

Males and females stay in or near their home range

year

round except during the rut.

During that time,

males may travel several extra miles outside their home

range in an effort to breed.

California

mule

deer

in

chaparral

zones breed

between mid-October and mid-December peaking in November.

Stag groups

(male deer)

ranking scheme

establish a hierarchy.

The

is established by threats of physical

strength with one rna le at tempting to scare away another.

Size,

weight and fitness have a good deal to do with

ranking.

Polygamous by nature,

males with higher rank

rut first and breed to as many females as possible.

Gestation lasts between 205 and 212 days

months).

In Southern California chaparral ranges,

are dropped

in April and May (Ashcraft,

Many fawns die shortly after birth.

p • 179 )

s u spec t s

that

this

is

due

fawns

1979, p. 179).

Ashcraft

to

(seven

(1979,

the mother ' s

43

improper

nourishment before

the birth.

First

time

mothers generally bear only one fawn. In succeeding years

they commonly bear two and sometimes three.

When it is

time to give birth, the doe finds a secluded spot in the

shrubs,

often

in a

riparian area,

where she drops her

five to eight pound offspring (Figure 9).

Trails and Deer Movements

A deer's daily routine includes feeding,

and resting.

watering

Deer generally develop a mass network of

trails to fulfill the various habitat uses with several

deer using a common path.

Trails are generally visible

and well defined, with vegetation often trampled and bare

soil occasionally exposed.

Routes circumvent dense over-

growth. Deer travel along livestock or equestrian trails

and roads, too,

if available and safe.

Several deer trails were located by the writer in

Cheeseboro Canyon between 1983 and 1985 and occasionally

deer

were

seen

along

them.

pinpoints these deer sighting.

Figure 10

(rear pocket)

The National Recreation

Area office maintains

the complete record of reported

sightings in the park.

The field map also distinguishes

between areas of light, moderate, and heavy use by deer.

Where trails were abundant and sightings occurred,

zone is classified as a heavy use area.

If trailing was

more sporadic and sightings less frequent,

labeled as moderate.

the

the area

Those areas unmarked receive

is

45

lighter use. Lower Cheeseboro had not been purchased by

the

National

Park

Service at

reconnaissance trips .and,

the

therefore,

time of

is not

the

field

included in

the descriptions.

Riparian areas,

the greatest use.

as well.

especially near a spring,

receive

Oak woodlands receive considerable use

Moderately used areas

include mixed chaparral

and coastal sage communities farther away from established

roads,

ranches,

and

residential development.

Moderately used areas are also found adjacent to the core

riparian zones.

On moderately used sites,

trails exist

but multiple trails crossing each other are not as common

and sightings are

less

frequent.

include those where forage

Lightly used areas

species are not abundant,

where an area has recently burned, or locations close to

development or human activity.

Areas of heaviest use

include Enchanting Forest,

riparian zones from Sandy Cliff Canyon to Dome Canyon,

Browse Bend, Quai 1 Uplands,

and Northwest Canyon.

Figure 4 for place name locations.)

(See

Moderately used

areas include the zones extending from the riparian areas

upslope to the north, east, and west boundaries.

Lightly

used areas are generally found in South Cheeseboro.

Deer were

lines.

Fences,

frequently sighted near park boundary

maintained by the National Park Service,

border all side of the Cheeseboro property.

At various

46

places along the fence,

enough for deer to

the barbed wire strands are low

jump.

Some lower strands are high

enough that deer can crawl under.

lower

than the

Boundary gates are

fence and can be hurdled easily.

Deer

jump fences without hesitation if they are less than four

foot tall.

The highest fence which Linsdale and Tomich

observed a deer jumping was 62 inches (1953, p. 296).

Cover

Cover assists deer

in escaping from predators and

intruders and protect them from the physical

especially changes

in temperature.

rugged topography as shelter.

elements,

Deer make use of

When spotted in Cheeseboro

Canyon the deer would often quickly travel over a ridge

and

down

into

an

adjacent

canyon

and out of

view.

Cheeseboro lends itself to this because there are several

small canyons off the main channel.

The

most

suitable

temperature

Mediterranean type habitat

heit.

the

for

deer

in

this

is 55 to 65 degrees Fahren-

Dasmann's research (1971, p. 20) indicates that in

southern coas ta 1 area

direct

Ca 1 i forn ia,

sun light on hot summer days.

and shadows change,

location to be

sweat

of

glands

maintain a

When the sunlight

move

to

Since deer have no

another

suitable body temperature.

cold weather,

avoid

the deer may change their bedding

in constant shade.

they

deer

deer move

microclimate to

By contrast,

in

from cooler canyons and north

47

facing slopes to warmer open areas on south facing and

leeward slopes to keep warm {Taber, 1958, p. 22}.

these cold periods,

During

deer hair stands erect and at right

angles to the body to maintain warmth.

Since deer use vegetation for foraging and cover,

there is a careful natural balance between deer consumption of

forage and restraint from browsing.

On ranges

where deer numbers do not exceed carrying capacity, deer

do not deplete their own cover.

protective vegetation has been

discontinued

{Dasmann,

If too much of the

removed,

1981, p. 19}.

browsing

is

A shrub or tree

serves as a hiding place if it is at least five feet tall

{Kerr, 1979, p. 43}.

Deer habitat is most suitable when islands of cover

are interspersed with open areas.

These "edges" create

good browsing conditions while maintaining cover nearby.

Under optimum conditions a range contains 60 percent open

forage and 40 percent cover.

ten to thirty acre

According to one authority,

islands of cover

interspersed with

slightly larger open areas provide the best ratio {Kerr,

1979, pp. 43-44).

---

~

··-

-

--·-

----

-~--

-------·

-

'

CHAPTER IV

THREATS TO HABITAT PRESERVATION IN CHEESEBORO CANYON

Livestock Grazing

Cattle

grazing

California since

Livestock,

has

prevalent

their

dense

and

introduced many

forbs

concentrations

in

took a heavy toll on native grasslands

(California Department of Forestry,

Spaniards

in Southern

Spanish settlement in the late 1700s.

because of

particular areas,

been

into the

1981, p.

M~diterranean

76).

The

annual grasses

western United States.

Annuals

competed with natives and often became dominant species

by the

late 1800s and early 1900s when the area was

overgrazed during drought conditions

ment of Forestry,

1981, p. 76}.

(California Depart-

The present day annual

grasslands in Southern California have largely replaced

native perennial grasslands (Longhurst, 1976, p. 80}.

Cheeseboro Canyon was part of the San Buenaventura

and

San

p. 11).

Fernando mission

rangelands

(Donley,

1979,

After the mission period, the property was held

by private landowners until

purchased it in 1981.

the National Park Service

Cattle grazing had been common in

48

'

49

Cheeseboro Canyon for decades

p. 5).

(Ochsner, Plantrich, 1984,

Evidence of the impacts of grazing can be seen in

the various exotic plant species which have replaced

natural vegetation.

Impacts on vegetation and soils from cattle grazing

are

most

grasses

severe

and

in

the

forbs

riparian