CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

advertisement

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

CONSU!mR PERCEPTIONS AS A

GUIDE TO HOME HEALTH PLANNING

A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Public Health

by

Charlotte Lee Laubach

August, 1981

The Thesis of Charlotte Lee Laubach is approved:

California State University, Northridge

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are so many people who deserve recognition

for their contributions to this project.

First, I wish to express my gratitude and

appreciation to the directors and staff at National In-Home

Health Services who provided the setting for, generously

supported, and enthusiastically participated in this study.

Words cannot express my deep appreciation to Ruth Geagea,

Associate Director of Nursing Services and Director of

Educational Activities, and also a member of my thesis

committee.

Her personal interest, support and guidance

were invaluable to me.

I acknowledge my indebtedness to other members of

my committee, to Dr. Michael Kline for his constructive

criticism and enthusiasm, and to my chairman, Dr. Goteti

Krishnamurty for his patience, encouragement and counsel.

I also wish to express my thanks to Dr. Roberta

Madison for her assistance with analysis of the data.

To

Phyllis Mitchell, whose contributions reach far beyond

her typing skills, I express thanks also.

Last, and by no means least, I wish to express my

sincerest appreciation to my friends and family whose interest, encouragement and assistance sustained me

iii

throughout this project.

Very special thanks go to my

husband, Peter, and my four sons for their love and

understanding during my years in school.

iv

;.:

'

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRELIMINARIES

PAGE

APPROVAL •

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • •

iii

LIST OF TABLES

viii

ABSTRACT • • • •

X

CHAPTER

I.

I I.

INTRODUCTION • •

1

Statement of the Problem •

2

Statement of the Purpose

4

Objectives of the Study

4

Definitions

5

Limitations of the Study

6

LITERATURE REVIEW

7

Development of Consumer Role

7

Consumer Role in Health Services

Planning • • • . . . . • . • .

9

Home Health Care Services - Structure

and Utilization

. • • . .

11

Utilization

14

Perceptual Functioning .

15

Attitudinal Research .

17

Behavior of Older Adult

v

.

17

CHAPTER

PAGE

Similar Studies .

III.

• 18

METHODOLOGY

• 20

Target Population .

• • 20

Selection of Survey Instrument

• . 21

Selection of Study Sample .

.

.

• • 22

Construction of the Survey Instrument .

. 23

Pre-Test and Revisions

25

Implementation of the Survey

. 25

Collection and Organization of the Data

Follow-up of Non-Respondents

Organization of Data

~/

/'

'

. . . .

• • 27

.

Description of the Study Sample .

IV.

V.

26

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

•

•

30

•

• 35

Part

I.

Part

II.

Consumer Needs Responses . . . 45

Part III.

Rating of Consumer Responses

by Management Advisory

Committee

. . . • • . . . . . 57

SU}~RY,

Quality of Care Responses

29

. . 35

CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS . . 61

Summary . •

61

Limitations and Weaknesses of the Study

67

• • 68

Conclusions

. 69

Recommendations

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• • • 72

vi

'.··.i.,..

PAGE

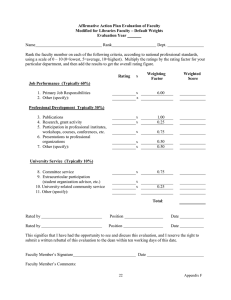

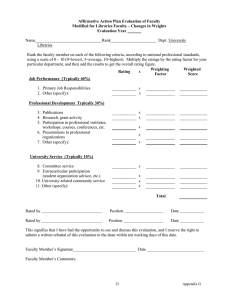

APPENDIXES . • •

78

A.

Questionnaire

79

B.

Cover Letter . .

80

C.

Management Advisory Committee Instrument

83

vii

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE

PAGE

lo

Response to Mailed Questionnaire

2o

Telephone Follow-up: Reasons for NonResponse to Questionnaire o o o o o o o o o 28

3o

Identification of Respondent to

Questionnaire o o o o o o o o

0

0

0

0

0

27

30

4o

Comparison of the Characteristics of

Patients in Sample by Office and Totals o o 32

5o

Patient Characteristics of Sample and

National Study (1978) o o o o o o o

o o 34

6.

Consumer Perceptions of Patient Teaching

o o 37

7o

Respondent by Interest in Additional

Information o o o o o o o o o o o o . o o o 39

8o

Consumer Perceptions of Delivery of Services

9

Consumer Perceptions of Quality of

Professional Staff o o o o

0

0

41

0

43

lOo

Health Education Needs

llo

Relationship of Survey Respondents to

Health Education Needs o o o

o o o • o 48

l2o

Supportive Service Needs

13o

Relationship of Living Arrangement with

Supportive Service Needs o o o o o o o o o 51

14o

Relationship of Age by Sex by Supportive

Service Needs

o o o . o o

o o o o o 53

15o

Needed Psychological Counseling by

Living Arrangement

o o o

46

0

viii

0

0

0

50

o . o o o 54

TABLE

16.

17.

18.

19.

PAGE

Interest in Attending Group Support

Meetings . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

Identification of Respondent Interested in

Group Meetings • • . . . . . . . .

56

Management Advisory Committee Rating of

Consumer Responses to Selected Variables •

58

Mean Rating Scores of Variable Categories

by Management Advisory Committee • . . . .

60

ix

ABSTRACT

CONSUMER PERCEPTIONS AS A

GUIDE TO HOME HEALTH PLANNING

by

Charlotte Lee Laubach

Master of Public Health

August 1981

This exploratory study was conducted to collect

and analyze consumer subjective responses toward home

health services, for the purpose of providing added perspective to agency performance evaluation, and to identify

needs which might suggest modification in planning and

delivery of agency services.

An interdisciplinary literature review was carried

out in the fields of Gerontology, Sociology, Psychology,

Health Services, Consumer Science and Attitudinal

Research.

Using the literature as a background and work-

ing closely with home health agency staff members a survey

questionnaire instrument was constructed.

X

The instrument

contained 19 items with Likert-type scale format being

used where attitudinal responses were desired.

Following

pre-testing and revision the instrument was administered

to 400 randomly selected horne health care consumers who

had received service from the agency during the previous

eight months.

One hundred and forty-three usable ques-

tionnaires were obtained for the study.

Questionnaire response data was coded and mean

frequencies, statistics and cross-tabulations were obtained using the Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences.

Data was tabulated and analyzed.

A second instrument was constructed to collect

ratings of consumer response data by the Management Advisory Committee.

The committee independently rated

those responses from the first questionnaire which pertained to quality of care (teaching, delivery of services

and quality of the professional staff) and consumer needs

(consumer awareness or Health Education needs and support

services needs).

Mean rating scores were tabulated and

analyzed.

The Advisory Committee indicated that they were

most satisfied with consumer perceptions of quality of

care, less satisfied with the unrnet needs expressed by

consumers, and least satisfied with the lack of consumer

awareness of the potential of horne health care services.

xi

Conclusions of the study were consistent with

beliefs held by agency staff personnel prior to the study.

Most of the consumers felt that they were receiving comprehensive and quality care.

Many were unaware or misin-

formed about potential services available from a home

health agency.

A number of home health consumers, espe-

cially elderly persons living alone, felt the need for

more supportive services than they were able to obtain.

Recommendations related to the needs of the home health

care consumer, and to the collection of consumer perceptions.

xii

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

"Good Health care is a basic human right!"

(58:528).

Good health care by recent definition, includes

the right of the consumer to be "heard" and to be "informed" in planning and delivering that health care (1:24)

(2).

This right has been encouraged and protected by

government regulations (U.S. Congress PL 93641)

(OAA).

Planning and responding to consumer needs are considered

essential characteristics of good health services (16:13)

(19:14).

Home-health care is a new and rapidly developing

industry due to the increase of the elderly in our population, the extension of average life-expectancy and rising costs of institutional care (9:14).

Growth has been

spurred by the financial support from government through

Medicare and Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid).

This

growth of home health services accompanied by increased

emphasis on consumer involvement has created a need for

reliable and unbiased methods of eliciting consumer responses.

In 1976 a National Public Health Task Force on

Research and Evaluation suggested in a policy statement

that "research and evaluation activities be designed to

1

2

assess variables such as . • . , consumer satisfaction,

(54:2).

A national professional Horne Health Associ-

ation advocates that "planning strategies should be responsive to gaps in service programs and unrnet needs as

they are identified" (9:4).

Health Services provided away

from the agency setting present a challenge to adrninistrators in evaluating the quality of care.

In an atmosphere

that lends itself to the exploitation of the homebound

and their rights, monitoring and maintaining professional

standards of care is extremely critical (16:13).

Bloom suggests that social research be carried out

which concerns "the sensitivity to and responsibility for

the well being of the participant" (6:292).

An Administration on Aging goal suggests that we

learn about the characteristics, attitudes and behaviors

of older persons, which will require consideration in relation to existing and future policies and program designs

(40:v).

Effective methods for collecting and analyzing

consumer input from a predominantly ill, elderly and hornebound population have not yet been established.

Statement of the Problem

The rationale for consumer involvement is that

it is

An opportunity for the patient to retrieve the

bargaining power dissipated through third party

payment mechanisms, but also to insure that the

3

services and care provided to him will be of

high quality, at a reasonable cost, and relevant

and responsive to the needs of those for whom

they are intended. Community participation in

health services also serves to raise the consciousness of the people regarding the definition of good health care and how to get it

(17:52).

With government support through financial

reimbursements Medicare and Medi-Cal (Medicaid) , also

come government regulations.

Health planners must now

include a social perspective to professional and organizational planning strategies.

A national professional

Home Health Association policy directs that

Community home care systems should be based on

continuous planning.

. Planning strategies

should be responsive to gaps in service programs

and unmet needs as they are identified (11:4).

During this author's internship with a community

based home health agency, it was revealed that the Subcommittee on Agency Evaluation had recommended that an

agency-wide survey of consumers (patients and/or families)

be conducted.

Data from the survey would be used by the

agency as a basis for program evaluation and also as a

resource for program modification and planning.

Discus-

sions with staff members at all levels revealed a high

interest in obtaining and assessing consumer perceptions

toward the services they had received.

In the past, while

helping elderly friends who were receiving Horne Health

services (from a different Home Health Agency), the author

4

had observed the need for home health care services to

be more responsive and relevant to the consumer.

Statement of the Purpose

The purpose of this study was to collect consumer

subjective responses, regarding their perceptions of home

health care services received from a community-based Home

Health Care Agency.

These responses were to be analyzed

and used as one perspective for agency evaluation of their

services and also as a basis for program modification and

planning.

The substantive hypothesis is:

(a) The following specific questions will be

answered by the data:

(1) Do home health consumers feel that they

are receiving comprehensive and quality

services?

(2) I'Vhich specific needs of the home health

consumer are not being met?

Objectives of the Study

There were two main objectives of this study.

The

first was to collect and analyze consumer perceptions of

home health care services.

The second objective was to

identify needs perceived by home health care consumers.

5

Definitions:

Home Health Agency:

A Home Health Agency is one which

basically provides multidisciplinary health care on a

family-centered basis to the sick, disabled, and injured

in their place of residence.

It provides the interweaving

of skills of a variety of health workers who participate

in planning and implementing community health programs.

It may also provide programs in addition to care of the

sick ( 50 : 18) .

Service:

A service refers to the discipline utilized to

give care to the family or patient:

nursing, nutrition,

occupational therapy, physical therapy, physician services, social work, speech pathology services, and homemaker home health aide services.

It also includes support

elements such as medical supplies and equipment, transportation, laboratory services (50:18).

Consumer:

The patient, and or family or household members

who are involved in his care, who have received services

provided by a Home Health Agency.

Perceptions:

The process of evaluating the information

gathered by the senses and "giving it meaning" (3:57).

Consumerism:

The response of people and organizations to

consumer problems and dissatisfactions.

6

Chronic disease:

(from the Commission on Chronic Illness)

All impairments or deviations from normal which have one

or more of the following characteristics:

are permanent;

leave residual disability; are caused by non-reversible

pathological alterations; require special training of the

patient for rehabilitation; may be expected to require a

long period of supervision, observation or care (45:1).

Limitations of the Study

The study population was limited to patients

and/or families who had received services from the agency

within the past eight months.

If the patient had died

within the past six weeks the family was excluded from

the study.

Poor general health status and/or advanced

old age with its frequently accompanying memory and endurance restrictions may have an impact on the quality

and quantity of responses as well as overall return rate

of the questionnaire.

This was a one-time study for which the agency

provided financial support with budget restrictions.

Agency limitations on the gathering of sensitive information, such as income and education, precluded the use of

such information in this study.

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

A search of the literature was conducted to

assist the researcher in the collection and analysis of

home health consumer attitudes.

This search called for a

multi-disciplinary approach involving the fields of

Gerontology, Sociology, Psychology, Health Services, Consumer Science, and Attitudinal Research.

Five areas of focus relevant to the study were

l.

The health care consumer role--its development and

significance in health care planning.

2.

The structure and utilization of home health care

services.

3.

Perceptual functioning--including age related factors.

4.

Attitudinal research--including age related factors.

5.

Health behavior--including age related factors.

Development of Consumer Role

Consumerism became a dominant political movement

in the sixties.

A great deal has been written about its

development and significance, but only in the last decade

has the health care consumer received much literary attention.

Aaker describes the growth of the consumer

7

8

concept and refers to John F. Kennedy•s message, when he

charged the Congress to

11

meet its responsibility to con-

sumers in the exercise of their rights.

The right to

safety, right to be informed, right to choose and the

right to be heard ...

Appointment of the first Consumer

Advisory Council followed.

This Council identified ten

fields of importance to consumers; the tenth and last on

the list was medical care (1:25).

Novello also reviews

the historical background of consumerism, and the subsequent legislation which has expanded the role of the consumer in the health care process.

Significant consumer

legislation discussed included the Hill-Burton Act of

1946, PL 89-749 in 1966, Amendment to Section 314 of the

Public Health Service Act and in 1974 PL 93-641, the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act.

She

identifies four major characteristics of the consumer•s

role which she feels are needed to improve the health system.

One of these is .. participation in direct health ser-

vices ...

She suggests that the

11

most accepted role of the

consumer is in planning .. (32:3).

The consumer•s role in direct health services is

supported by the Patient•s Bill of Rights (American Hospital Association, 1972) and through the use of ombudsmen

or patient representatives.

Although the Patient•s Bill

of Rights has been modified to cover the home health

9

consumer, the use of ombudsmen in a broad based community

setting would be costly and time consuming.

At the pres-

ent time patients must report dissatisfaction with services by talking directly to the provider, the home health

agency, or if they wish anonymity by calling the County

Health Services.

Consumer Role in Health Services Planning

Most reports in the literature substantiate the

belief that the use of consumer input is an important element in evaluating program effectiveness and planning that

is responsive and relevant.

Schmidt reports that patient needs have often been

evaluated by health status reports or in the case of the

elderly and infirm by those caring for them, or medical

personnel.

Often these reported needs have been found to

be quite different or of a different intensity than those

perceived by the patient himself (39:544).

Hochbaum feels

that "If people are involved in planning it gives them

some feeling of control--a visible symbol of their 'equal

human rights'" (15:267-269).

Sociological literature views the consumer rule

as one of little power and urges the consumer to take a

more active role.

"Consumer awareness of their role in

affecting the output of the health system must be extended

to include awareness of their input contribution and

10

primarily the need for consumer effectiveness on the

entire internal social organization of health" (26:23,24).

The sociologists suggest that social science

should be the discipline to evaluate consumer participation as a means to improve health services.

Social scientists .

. come closest to meeting

the professional and technical requirements for

reliable and objective investigations both of

the concept of consumer participation in the

planning of health services and of the various

operational systems based upon it.

. Such

scientific investigations . . . are desperately

and urgently needed (15:267).

The implementation of consumer participation in

the planning process is still in the exploratory and developmental stage.

In a review of health consumerism is-

sues, Feingold presents a ladder representing different

levels of consumer participation.

The lowest degree is

referred to as "informing" where there is information presented to consumers but no allowance is made for feedback

or discussion.

The second level he calls "consultation"

where the citizen's perceptions are elicited.

He suggests

that it is a step in the right direction but that there

is no assurance that the information will be used (38:

157,158).

A report on a workshop for health professionals

to discuss the new consumer role, reported skepticism

about learning "how to hear from those who need to be

heard"

(56:86).

Professional planners felt that consumer

11

interest is only shown when the patient is ill (56:87).

One participant suggested "Consumers could evaluate the

care they receive by a means of a questionnaire asking

what they thought of treatment received" (56: 87, 88).

Home Health Care Services Structure and Utilization

A

rapid growth in home health agencies followed

the advent of Medicare and Medi-Cal (Medicaid).

In 1980

there were approximately 2,500 home health agencies in the

United States (42:23).

Home health agencies are public

or private agencies that provide a coordinated multidisciplinary range of health care services to the homebound patient who needs skilled health care, on a parttime, intermittent basis.

Most of the time these services

are paid for by hospital and medical insurance plans

developed by Medicare (51).

In recent years private in-

surance companies have begun to recognize the cost benefits of covering health services in the home, instead of

in institutions, and an ever-increasing number are willingly providing reimbursement for in-home services.

A

very small percent of services are paid for by private

individuals.

"Your Medicare Handbook" printed in 1975, lists

services which are covered by Medicare and defines

12

eligibility requirements for hospital and medical

insurance coverage (51:35-37).

Home Health Services Covered by Medicare

Medicare can pay for:

1.

2.

3.

Part-time skilled nursing care

Physical therapy

Speech therapy

If you need part-time skilled nursing care,

physical therapy, or speech therapy, Medicare

can also pay for:

- Occupational therapy

- Part-time services of home health

aides

- J1.1edical social services

- Medical supplies and equipment

provided by the agency

Home Health Services Not Covered by Medicare

Medicare cannot pay for these items.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Full-time nursing care at home

Drugs and biologicals

Meals delivered to your home

Homemaker services

When Hospital Insurance Pays for Home Health Care

Medicare's hospital insurance (Plan A) can

pay for home health visits if six conditions are

met. All six conditions must be met. These

conditions are:

(1) you were in a qualifying

hospital for at least 3 days in a row, (2) the

home health care is for further treatment of a

condition which was treated in a hospital or

skilled nursing facility, (3) the care you need

includes part-time skilled nursing care, physical therapy, or speech therapy, (4) you are

confined to your home, (5) a doctor determines

you need home health care and sets up a home

health plan for you within 14 days after your

discharge from a hospital or participating

skilled nursing facility, and (6) the home

13

health agency providing services is

participating in Medicare.

Under these conditions, hospital insurance

can pay the full cost of up to 100 horne health

visits after the start of one benefit period

and before the start of another.

Payment for

these visits can be made for up to a year following your most recent discharge from a hospital or participating skilled nursing facility.

You may be charged only for any non-covered

services you receive.

The horne health agency will submit the

claim for payment. You don't have to send

in any bills yourself.

When Medical Insurance Pays for Horne Health Care

Medicare's medical insurance (Plan B) can

help pay for up to 100 horne health visits in a

calendar year. You do not have to have a 3-day

stay in the hospital for medical insurance to

pay for horne health care. But medical insurance

can pay for the visits only if four conditions

are met. All four conditions must be met. These

conditions are:

(1) you need part-time skilled

nursing care or physical or speech therapy, (2) a

doctor determines you need the services and sets

up a plan for horne health care, (3) you are confined to your horne, and (4) the horne health agency

providing services is participating in Medicare.

Medical insurance can also pay for horne health

visits if this care is still needed after you

have used up the 100 visits covered under hospital

insurance.

After you meet the $60 yearly deductible,

medical insurance pays the full costs for

covered horne health services in each calendar

year. You may be charged only for any noncovered services you receive.

The horne health agency always submits the

medical insurance claim for horne health care.

You don't have to send in any bills yourself.

14

A revised, updated, edition of this book is soon

to be released.

Although home health agencies participating in

Medicare receive a very high percentage of their reimbursement for covered services from Medicare insurance

plans they still receive less than one percent of the

Medicare dollar.

Utilization

30 to 40% of patients in nursing homes could be

safely and effectively treated in the home . .

10% of patients in acute hospitals could be

managed at home

is Dr. Schrifter's interpretation of reports submitted

by the United States General Accounting Office (42:26).

Two doctors claim restrictive eligibility

criteria, over-regulation and inadequate reimbursement

from government sources are some of the reasons that such

a small portion of the Medicare budget is spent for services; services which they claim can improve the patients'

quality of life and reduce the costs of institutionalization dramatically (31:37-41)

(42:23-28).

The fact that

many physicians are unaware of potential services available from home health agencies reduces their utilization

rate.

A study of 600 physicians in New York State re-

vealed that one fourth were unaware of home health services (42:24).

15

Physicians' concerns over loss of control and

malpractice liability, restrict the prescribing of home

services (42:26), even though the patient is more happy

and comfortable at home and would prefer to be there.

Perceptual Functioning

The senses provide the means for assembling and

classifying information but they do not evaluate it. The process of evaluating the information gathered by the senses and giving it

meaning is called perception (3:57).

McKinley writes that the process of perception or

of "evaluating the information" is influenced by both external (social, cultural, economic) and internal (psychological) factors (29:285).

Botwinick agrees with McKinley and also claims

that the processes of perception and the processes of

sensation cannot be separated (7:156-157).

For the older

person, the ability to interpret what is going on around

him is affected by changes in perceptual processing and

sensory processing attributable to physiological aging

(28:9).

These changes in older persons reduce the rate

at which incoming information is integrated.

This is re-

£erred to, in the literature, as "perceptual slowing"

(28:9).

Atchley discusses similar findings in regard to

"perceptual slowing" but feels that they do not seriously

affect the behavior of the individual until after the age

of seventy.

Botwinick also reports on disparate views

16

presented in the literature, regarding the importance of

"slowing" to cognitive and perceptual abilities.

He con-

cludes, by proclaiming, that slowing with age is experienced by everyone, appears to be independent of culture

and health status and is related to vital functions

(7:203).

Factors which may reduce "slowing" include

exercise habits, opportunities for learning, motivational

activities and individual differences (7:203).

No clear-

cut pattern for perceptual functioning with age was found

in the literature.

Individual differences alone, are of

such a wide range that many old people respond more

quickly than many young adults (7:205).

Since sensory functioning is reported to be

inseparable from perceptual functioning, the literature

was examined on physiological aging of sensory organs.

Age associated changes in peripheral sensory apparatus

are reported to alter the quality and quantity of information received from the environment (28:9).

These sen-

sory losses associated with aging are well documented in

the literature ( 6)

( 3)

(53) .

Impairments in vision and hearing are agreed to

have the most impact on perception, with losses in taste

and touch also having a significant effect.

Other

17

physical and psychological factors involving perception

described are emotionality, mentation and intelligence

(6:292).

Attitudinal Research

No attempt will be made to report on the

literature examined on behavioral research.

Discussion

of some advantages and disadvantages of survey research

methods will be discussed under methodology and data

analysis.

Behavior of Older Adult

An understanding of age and its relationship to

behavior, prior to comparing age related behaviors with

selected variables was needed.

That age related behavior

patterns are extremely varied was shown.

Older people show more variability of lifestyles

and personalities than any other (3:53).

Schutz, also reports that there is a wide range

of behavior in the elderly, and his studies examine the

behavior of older adults in relation to lifestyle

(40:152-159).

Botwinick completed an extensive review of the

literature on aging and behavior.

Some of his findings

were (1) the elderly show reluctance to be involved in

decision-making and may exhibit a pattern of avoidance or

non-commitment; that is, they are more inclined to give

18

"no opinion" or "don't know" responses.

( 2) There are

disparate study results regarding the relationship between

levels of "opinionation" and education (7:138-139).

A

study by Gergen and Back indicated that the elderly with

a high school education were more likely to exhibit low

"opinionation."

A previous study done by Botwinick him-

self showed that "opinionation" was higher among those

with a h·igh school education.

He suggests that "the role

of education in the cautiousness of later life requires

further investigation" (7:140).

Similar Studies

Very few actual studies have been done to examine

consumer behavior of the elderly with regard to health

care.

Schutz, Baird and Hawkes report on a study done in

1979, examining the relationship of lifestyle and adult

consumer behavior.

behavior.

Only one chapter deals with health

Unfortunately, only 9 people in this study had

received home health services.

Some conclusions reported

were that elderly people

are generally satisfied with health care services

and express favorable attitudes toward the leadership, professional competency and personal

qualities of health professionals.

They have

found greater concern for economic, time-related,

convenience, and psycho-sociological factors

than for quality of care or where to go for

health care (40:113).

19

Those least satisfied with health care services were

women, blacks and Medicaid recipients (40:113).

Actually there was not a high relationship between

age and consumer health behavior except in evaluating the

competence of doctors, where men over 65 gave them a positive ra-ting that was significant at the .05 level (40:113).

Those in poor health and needing a support

system of friends find the medical care system

least responsive to their needs (40:124).

Bloom discusses problems associated with

interviewing the elderly.

Although directed to those

doing personal interviewing the physical limitations

described are common to respondents of mailed questionnaires.

Physical disabilities which may affect the qual-

ity of data and/or response rate include impaired vision

and/or hearing, physical stamina, language function, emotionality and intellectual capacities (6:292-299).

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

A research study was conducted to collect and

analyze consumer perceptions toward health care services

received from a selected home health care agency.

Re-

sponses would be used by the agency to assist in evaluating their services and to identify consumer needs which

are not being met.

Procedures discussed in this chapter

will include, description of the target population, selection of the survey instrument, selection of the sample,

construction and approval of the survey instrument, pretesting and revision of the instrument, implementation of

the survey, collection and organization of the data and

analysis of the data.

Also discussed will be the use of

a second instrument to obtain ratings by the Management

Advisory Committee of selected data from the first instrument.

These ratings will be analyzed and discussed.

Target Population

The target population consisted of consumers

(patients and/or families) who had received services from

National In-Home Health Services, a community-based home

health agency.

These consumers resided in widely

20

21

dispersed geographic locations covering a large portion

of Los Angeles County, including Santa Clarita Valley,

Glendale, San Fernando Valley and the west side of Los

Angeles, the service areas covered by either the Los

Angeles or San Fernando Valley branches of the agency.

Residential settings ranged from the densely populated

inner city to isolated rural ones.

alone or with an elderly spouse.

A large portion lived

Most of the patients

were over age 65, were predominantly female and had a high

incidence of one or more chronic diseases.

Selection of Survey Instrument

A mailed questionnaire was selected to collect

consumer responses for the following reasons.

1.

Its capability of reaching a larger number of people

living in widely dispersed geographic locations, with

less cost of money and human resources (43:238-245).

2.

Higher quality data can be expected when anonymity

and confidentiality are assured (43:238-245).

3.

Written responses allow the elderly respondent time

to deliberate, time to consult with family members

and thereby presenting a more reliable, better overall

response (43:240).

4.

Self-responding completion, allows self-pacing, that

can be done in small increments or delayed temporarily if patient's health status is lower than normal.

22

This method also reduces fatigue and avoids

emotionality (39:545).

The use of a mailed questionnaire was approved by

the agency and financial support (a budget of $400) was

allocated.

Selection of Study Sample

The budget provided resources which permitted 400

questionnaires to be used in the study.

Costs included

printing and mailing of a four-page questionnaire and

cover letter accompanied by a stamped return envelope.

Four hundred patients were selected randomly from the target population.

Starting with the current patient roster

and working back in time, patients were selected by rolling dice.

If the numbers presented, summed to an equal

number, the patient was chosen for the study, if odd, they

were rejected.

The sample included patients who had re-

ceived home health services between April 1980 and September 1979.

This selection included 120 patients from the

Los Angeles office and 280 from the Valley office.

The

numbers selected from each office correspond to the ratio

of patients serviced by that office in relationship to

total agency clients--approximately 1-3.

23

Construction of the Survey

Instrument

The purpose of the study, as stated in the

previous chapte4was to collect consumer subjective responses regarding their perceptions to home health care

services.

1.

Two questions were to be answered by the data:

Do home health consumers feel that they are receiving

comprehensive and quality services?

2.

Which specific needs of the home health consumer are

not being met?

Agency policies and objectives were reviewed to

identify content areas to be examined in program evaluation, which would suggest "comprehensive and quality services."

Personal interviews were conducted, by the

researcher, with the Management Advisory Committee, to

better understand various dimensions of the content areas

to be examined and identify other subject areas, that they

deemed useful in the study.

Based on the objectives of the study, the policies,

purposes and objectives of the agency and discussions with

management advisory staff personnel, three main content

areas were established to examine data for "comprehensive

and quality services" or to answer the first question.

1.

Teaching

2.

Delivery of Services

24

I

I

~ I

3.

Quality of Professional Staff

The identification of needs which are related to

agency services was also considered important to quality

of care evaluation.

The second question was approached by seeking to

identify all needs, both perceived and unperceived, of

the horne health consumer.

Questions which would elicit the data desired

were formulated and organized into a 19 item questionnaire

format.

This process was guided by reviewing attitudinal

research literature by Kerlinger, Parten, Isaac and

Miller (23)

(34)

(20)

(30).

Feedback from agency staff

suggested additional considerations.

Identification information, not available from

patients' records, was requested.

Questions asking for

sensitive information such as educational level or income

were not included.

Most of the questionnaire items asked for a fixedalternative response.

These included dichotomous choice

questions (yes or no) or selection of "appropriate response" questions.

Likert-type summated rating scales

were used when attitudinal (perceptual) information was

sought.

Some open-ended questions were included to probe

for additional information.

25

The questionnaire was then submitted to the

Management Advisory Committee for review and comment.

Their input added validity to the individual questions.

Modifications were performed.

Two research methodology

specialists were asked to review and comment on the questionnaire and appropriate revisions were made.

Two

elderly women, who had received home health services in

the past, were also asked to review and comment.

No re-

visions were indicated as a result of this step.

As a final step, the full agency staff was asked

to review and comment.

Agency approval was granted.

A

cover letter to accompany the questionnaire was written

and approved.

Its purpose was to explain the purpose of

the questionnaire and to encourage consumer response.

(Appendixes 1 and 2.)

Pre-Test and Revisions

The survey instrument (questionnaire) was pretested on 50 members of the sample population who had

received services from the Valley office.

Two very minor

revisions were made in the instrument as a result of the

pre-test but no other problems were identified.

Implementation of the Survey

Questionnaires were printed in two colors to

identify which office had provided services.

Yellow

26

questionnaires were sent to 120 patients who had received

services from the Los Angeles office and the remaining 230

sample members, who had received services from the Valley

office, received white one.

(A code number, representing

the patient's record number, was placed above the return

address of the return envelope, so that data from the

patient's record could be obtained to facilitate analysis

of selected responses.)

Collection and Organization

of the Data

The rate of response from the 400 questionnaires

is presented in Table 1.

Overall response rate was 35.8

percent which netted 143 usable questionnaires for the

study.

Individual office rates ranged closely with 36

percent from the Valley consumers and 34 percent from Los

Angeles consumers.

Nine of the undeliverable question-

naires that were returned had been sent to families where

the patient had died.

The remaining ten had post office

notices attached, stating that there was no forwarding

address.

Two questionnaires returned without data indi-

cated that the patient had died, and the other stated

that patient had been readmitted to the hospital.

Ten

post office notices informed the researcher that the questionnaire had been forwarded to a new address.

27

Table 1

Response to Mailed Questionnaire

Valley

Los Angeles

Total

280

120

400

116

11

3

49

8

0

165

19

3

Number of questionnaires

in study

120

41

Percentages of responses

to questionnaires in

sample study

36

34

Number of questionnaires

mailed

Number of questionnaires

returned not deliverable

without data

-

-

143

35.8

Follow-up of Non-Respondents

The researcher had planned to make ten follow-up

contacts with non-respondents, to complete questionnaires

and to look for non-respondent biases.

After 22 follow-up

telephone contacts, only three had been reached who were

able to complete a questionnaire.

When offered the al-

ternative of completing one by telephone or having a horne

interview, all three chose to respond by telephone.

The

responses from these surveys closely resembled the mean

percentage ratings of the consumers who had returned

questionnaires.

No response bias was identified.

Data

from these questionnaires was not included in the study.

28

Based on the follow-up telephone calls, the reasons for

non-response were attributed to a variety of factors,

with death of the patient representing more than onequarter of them.

More than one-quarter of them were

unable due to health status.

Table 2

Telephone Follow-up:

Reasons for Non-Response

to Questionnaire

Number

NonResponses

Reasons for Non-Response

%

NonResponses

l.

Consumer stated questionnaire

not received (questionaire

completed by telephone)

3

13.6

2.

Expiration of Patient

6

27.2

3.

Physical weakness--mental

confusion

3

13.6

4.

Patient now in Nursing Home

3

13.6

5.

Readmitted to Hospital

l

4.6

6.

Language Barrier (Hispanic

household)

l

4.6

7.

Very short duration of

services (2-3 visits)

2

9.1

8.

Unable to locate patient

by telephone

2

9.1

9.

Stated that questionnaire

had been. returned

l

4.6

TOTAL

22

100%

29

Following follow-up contacts it was observed that

of the questionnaires mailed, 10 were undeliverable due

to no forwarding address.

new address.

Ten had to be forwarded to a

Seventeen were not returned or were returned

unopened or without data in cases where the patient had

died.

Eight were not returned or were returned without

data in cases where patient's health status was reduced

(confusion, weakness, institutionalization).

These num-

bers represent 45 recipients or more than 11 percent of

the sample population suggesting that morbidity, mortality

and fluctuating places of residence may have had considerable impact on the questionnaire response rate.

Organization of Data

Responses from the questionnaires were examined

for reliability, appropriateness and inconsistency.

The

data was then coded, cards were punched and using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences frequencies,

statistics and cross-tabulations were computed.

Results

were tabulated to prepare for analysis.

A second instrument was developed to assess the

Management Advisory Committee's ratings of consumer

responses, to achieve a broader-based, more objective

assessment of the data.

30

Description of the Study Sample

Respondents.

For purposes of this study the

consumer is defined as the person or persons who responded

to the questionnaire.

Table 3 shows that more than half

of the questionnaires were completed by the patient, 36

percent by a family member, and a little over 12 percent

by patient and family together.

Less than 2 percent of

respondents were unknown.

Table 3

Identification of Respondent to Questionnaire

Number

of

Responses

Respondent

Percent

of

Responses

Patient

70

50.4

Family

50

36.0

17

12.2

6

1.4

Patient

&

Family

Unknown

TOTAL

143

100%

While data from the questionnaire was supplied by

respondents, it is important for the reader to recognize

that patient characteristics data (age, sex, living arrangement, primary and secondary diagnosis) was obtained

31

from the patient's record and describes the patient who

directly received the horne health services.

Patient Characteristics.

A comparison of the

Valley patient characteristics, with those of Los Angeles

patients, reveals minor differences (Table 4).

The Los

Angeles sample included about 6 percent more females and

a little more than 6 percent more patients in the over-60

age group, than the Valley sample.

There was only a small

difference in numbers living alone (less than 3 percent).

The biggest difference was in the number living with an

older person or a younger person.

Los Angeles patients

were 13 percent more likely to live with an older person

while Valley patients were about 13 percent more likely

to be living with a younger person.

Los Angeles patients

had a higher incidence of heart and circulatory problems

(6%), CVA (3%) but were 6 percent less likely to have

musculo-skeletal problems and 4 percent less likely to

have diabetes.

Discussion.

The higher percentage of over 60-

year-olds in the Los Angeles area may be a result of population distribution, as a higher concentration of elderly

people are reported to live in the Los Angeles office

area.

Studies show that in an elderly population there

is usually a higher percentage of women and a higher

32

Table 4

Comparison of the Characteristics of Patients

in Sample by Office and Totals

Patient

Characteristics

Valley

Office

N = 102

%

N

Sex:

Male

Female

Unknown

36

65

1

36

64

Age:

Under 40

40-59

60-80

Over 80

Unknown

3

10

57

31

1

3

10

56

31

Total over 60

LA Office

N = 41

N

%

12

28

1

30

69

3

26

12

7

63

29

86.27

Combined

Offices

N = 143

%

N

48

93

1

34

66

3

13

83

43

1

2

9

58.5

30

92

88.11

Living Arrangement:

Alone

With older person

(over 60)

With younger person

Deceased

Unknown

27

33

27.3

33.3

10

19

25

47.5

37

52

26

37

23

16

3

23.2

16.2

4

7

1

10

18.8

27

23

19

16

23

19

4

8

9

22.5

18.6

3.9

7.8

8.8

12

7

1

3

5

29

17

2

7

12

35

26

5

11

14

25

18

4

8

10

10

6

21

2

9.8

5.9

20.6

2.0

3

1

6

3

7

2

15

7

13

7

27

5

9

5

19

3.5

Primary Diagnosis:

Heart & Circulatory

Cancer

Urinary incant.

Respiratory Insuf.

CVA

Decubitus

Post-op Wound

Diabetes

Musculo-skeletal

Other

33

incidence of heart and circulatory problems.

Considering

age of population distribution, it appears that there is

a great deal of similarity in the two sample groups, suggesting that sampling error is low.

For the remainder of the study, the study sample

will be examined as one unit; the total number of patients

from both offices, unless stated otherwise.

Overall study sample characteristics show strong

similarities with those of patients in a national study

in 1978 which involved 11,182 patients from 19 agencies

across the nation (25:3-7).

Table 5 shows identical percentages of male and

female distribution.

Although slightly different age

intervals are reported, both groups still had between 50

and 60 percent in the

~0

to 80 year age range.

percent more of the study sample (32%)

in the national study (29%).

Only 3

lived alone than

34

Table 5

Patient Characteristics of Sample and

National Study (1978)

Patient Characteristics

Sex:

Age:

Percent of

Sample

Percent of

National Study

(1978)

Male

34

34

Female

66 •

66

60-80 years

59

50

63-81 years

32

29

Heart and Circulatory

25

27

Neoplasms

18

13

Musculo-skeletal

19

8

Living Alone:

Primary Diagnosis:

CHAPTER IV

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

This chapter presents and discusses data obtained

from the survey questionnaire pertaining to specific questions stated in the purpose of the study.

Analysis and

discussion of the Management Advisory Committee's ratings

is also included.

Part I will look at the data for answers to the

first question.

Do home health consumers feel that they are

receiving comprehensive and quality services?

Part II will examine perceived needs and

unperceived needs, for an answer to the second question.

Are the needs of the home health consumer

being met?

Part III will present and discuss the Management

Advisory Committee's rating of

th~

data examined in Part

I and Part II.

Part I.

Quality of Care Responses

Items associated with quality of care were

structured under three main components; teaching, delivery

of services, and quality of professional staff.

associated with these components were

35

Variables

36

Teaching

Self-help encouraged

Technique

Effectiveness

Additional Information Desired

Delivery of Services

Reliability

Coordination

Time of Delivery

Quality of Professional Staff

Nurse

Home Health Aide

Physical Therapist

Occupational Therapist

Speech Therapist

Medical Social Worker

The following tables list these variables, number of

responses, frequency percentage responses and mean rating

of the sample responses by Management Advisory Committee.

Table 6 shows that 91 percent agreed that the patients

were encouraged to help themselves as much as they were

able, that 4.5 percent were undecided and that 1.5 percent

disagreed.

High quality of teaching techniques was agreed

on by 92 percent of the respondents.

were undecided or disagreed.

Less than 3 percent

A much higher percentage

Table 6

Consumer Perceptions of Patient Teaching

Questionnaire

Item #

Teaching Variables

#6

#7

#8

Self help encouraged

Technique

Effectiveness

#9

Additional Information

Diet

Treatment

Equipment

Drugs

Number

Respondents

133

137

123

Mean

Percentage Percentage Percentage Percentage

Not

Rating

Agree

Undecided

Disagree Applicable Score*

91

92.0

82.1

4.5

2.2

10.6

1.5

2.9

2.4

3.1

2.9

4.9

1.1

1.1

1.4

Percent of Sample

11

16

1

15

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

7.7

11.2

.7

10.5

2.2

2.3

1.5

2.0

*Ratings done by Management Advisory Committee are rated on a scale of 1-5.

v.

.....

38

(10.6) were undecided about teaching effectiveness

although the percentage who disagreed was slightly less

than for teaching techniques.

rate

(10~14

A lower consumer response

less) was also noted.

Discussion.

Wording of the question (Item 8) may

have suggested that professional staff would outline the

"course of an illness"--a procedure unlikely to be carried

out due to the unpredictable nature of many illnesses.

It is unclear how respondents rated the first three teaching variables when the health status of the patient restricted teaching efforts.

Did they rate how family mem-

bers were taught, or did they just not respond?

Two

written responses stated "patient was unable" and "patient

too sick."

A "not applicable" alternative would have been

helpful in interpretation of responses to Item 8.

Additional information was desired by a number of

respondents.

Eleven were interested in diet information,

16 in treatment, and 15 in drug information.

needed information about equipment.

One person

Cross tabulations

were made between "respondents" and "information desired"

to examine who desired what information.

Although num-

bers were too small to generalize findings to the sample

population, some interesting differences were noted

(Table 7).

Twice as many "patient" respondents (55%)

wanted additional information on diet and treatment than

Table 7

Respondent by Interest in Additional Information

Additional Information Desired

Respondent

Diet

Respondent

N

%

Treatment

%

N

%

N

Equipment

%

N

Drugs

%

N

Patient

70

49

6

55

8

50

1

100

3

20

Family

50

35

3

27.2

4

25

0

9

60

Patient & Family

17

12

1

9.09

3

18.75

0

---

2

13.33

6

4

1

9.09

1

6.25

-

--

1

6.67

1

100%

Other & Unknown

Total

143

100%

11 100%

16 100%

15 100%

w

\.0

40

did "family member" respondents.

However, three times as

many family member respondents wanted additional information about drugs than did "patient" respondents (60%).

Interest in treatment information was indicated by 11

percent of the study sample, followed closely by an interest- in drug information by over 10 percent.

Discussion.

Cross tabulations were computed for

"information desired .. by "primary diagnosis."

Since most

patients had more than one medical condition the results

were misleading and are not included.

A study done of

the general public on a group of people over the age of

45 reported that 22 percent of them would like to have

more information about diet, showing more interest in

diet information than the sample population (40:37).

Data describing delivery of service is presented in Table

8.

Ninety-one percent of the consumers felt they could

rely on staff visits most of the time, 6 percent some of

the time, and only 2 percent felt that the staff were

seldom reliable.

Adequate coordination of multiple ser-

vices was accomplished most of the time according to 75

percent of those who responded, 6.6 percent reported satisfaction some of the time and 2 percent felt that services had not been coordinated well.

Many patients do

not receive multiple services as indicated by 15.6 percent,

who reported that it was not applicable.

This probably

Table 8

Consumer Perceptions of Delivery of Services

Item #

Delivery of Service

Variables

Number

Respondents

Percentage

Response

Percentage

Response

Percentage

Response

Percentage

Response

most of

time

some of

time

seldom

not

applicable

Mean

Rating

Score*

#10

Reliability

136

91.2

5.9

2.2

7.1

1.6

#11

Coordination

122

75.4

6.6

2.5

15.6

2.1

#12

Inconvenient Hours

10

Yes

1.7

*Ratings done by Management Advisory Committee are rated on a scale of 1-5.

*'"

1--'

42

accounted for a lower response rate.

One respondent who

rated coordination of services negatively wrote that the

"patient was critically ill" and too tired for physical

therapy visits.

Ten people felt that the staff arrived

at inconvenient hours.

A high level of satisfaction with professional

staff was expressed (Table 9).

Professional nurses were

rated "very good" by 96.2 percent, satisfactory by 3.8

percent, and no one considered them unsatisfactory.

Discussion.

High ratings of professional staff

are consistent with those found in studies by Schutz

(40:113).

The quality of Horne Health Aide was agreed to be

very good by 79.1 percent.

The same percentage (10.4) of

respondents felt that quality was "satisfactory" as those

who felt that quality was "unsatisfactory."

Discussion.

Dissatisfaction is a result of unrnet

expectations (24:153).

There were respondents whore-

ported that they expected housekeeping, shopping and

transportation services; perhaps services they expected

of a Horne Health Aide.

One respondent wrote disparagingly

of a Horne Health Aide but an investigation revealed that

he was referring to a homemaker-chore person from

another agency.

Table 9

Consumer Perceptions of Quality of Professional Staff

Questionnaire

Item #

#12

Quality of

Professional

Staff Variables

Number

Respondents

Percentage

Response

Percentage

Response

Percentage

Response

Mean

Rating

Score*

N

very

good

satisf.

unsat.

104

96.2

3.8

--

Home Health Aide

67

79.1

10.4

Physical Therapist

46

91.3

8.7

Occupational

Therapist

3

67.0

--

33.0

2.9

Speech Therapist

5

--

---

1.2

13.1

2.4

Nurse

Medical Social

Worker

32

100.

65.6

31.2

10.4

--

1

1.8

1

* Ratings done by Management Advisory Committee are rated on a scale of 1-5.

*""

w

44

Physical therapists were also perceived to be

"very good" (91.3%) with 8.7 percent seeing them as "satisfactory" and no one giving them an unsatisfactory rating.

High ratings again are consistent with literature

cited above (40:113).

Only 2 percent of the sample received Occupational

Therapy and 3.5 percent Speech Therapy.

One consumer

rated the quality of the Occupational Therapist "unsatisfactory.

n

Medical social workers were rated "-very good"- by

65.6 percent of those who had received services, while

31.2 percent felt that their performance was only satisfactory and 3 percent were dissatisfied.

Discussion.

Again higher levels of expectation

may be related to levels of satisfaction (24:153).

response rate to this question was noted.

A low

Although 39

respondents indicated that they had received medical

social services only 32 rated this item.

Patients' rec-

ords indicate that 69 patients in the sample had actually

received their services.

This lack of awareness could be

due to the fact that in some cases only one visit was made.

It is possible also that the person receiving the visit

was different than the person responding to the questionna,ire.

45

Part II.

Consumer Needs Responses

Consumer needs were structured under two main

categories, Health Education Needs (consumer awareness of

services) and Supportive Service Needs (consumer needs}.

Variables analyzed were

Health Education Needs:

Needed more information before discharge

(Item 2, Part III)

Knew why eligible for services (Item 4)

Knew reimbursement source (Item 5}

Expected services not available (Item 7)

Supportive Service Needs:

Transportation (Item 16)

Psychological help (Item 16)

Housekeeping (Item 16)

Shopping (Item 16)

More visits (Item 16)

Willingness to attend group support

meetings (Item 18)

Table 10 presents data on the variables associated

with Health Education Needs.

Fifty-three percent felt

that they would have been helped by "having a better

understanding" about home health services at time of

discharge.

Table 10

Health Education Needs

Questionnaire

Item #

Health Education Variables

N

Percentage

Response

Yes

Percentage

Response

No

#2

Needed more information before

discharge

77

#4

Knew why eligible for services

134

87.3

12.7

1.8

#5

Knew reimbursement source

140

77.8

22.2

2.1

94

18.1

81.9

2.2

#17

Expected services not available

53

Mean

Rating

Score*

1.9

* Ratings done by Management Advisory Committee are rated on a scale of 1-5.

.j::.

0"\

47

Discussion.

Since many of the patients are

readmissions and already are aware of services, one might

suspect that more than 53 percent of first time patients

need to know more about potential services.

A poignant

message was written by one respondent.

Wish I knew of Horne Health Services.

I found

out about it on my mother's last day in hospital

and nurse found me crying.

I did not want my

mother sent to a convalescent hospital.

To the question regarding eligibility, 12.7

percent of the respondents did not respond or responded

incorrectly.

As long as one appropriate criteria for

eligibility was identified, no penalty was assessed for

also checking secondary services such as social services

or occupational therapy.

An even larger 22.2 percent of

respondents did not accurately know how horne health services were paid for.

The largest misconception occurred

among the elderly who were eligible for Medicare A and B

and Medi-Cal.

Medi-Cal was credited with providing reirn-

bursernent much more frequently than it actually does.

Inappropriate expectations (services expected

for which horne health agencies are not reimbursed) were

held by 18.1 percent of those who responded to Item 17.

Table 11 shows the relationship between

respondents and lack of awareness of horne health services.

Half of those who wanted more information about horne

health services were the patients themselves (50%).

A

Table ll

Relationship of Survey Respondents to Health Education Needs

Understand

Home Health

Respondent

Did not know

eligibility

Did not know

Reimbursement

N

%

N

%

N

%

Patient

70

49

24

50

9

53

14

45

ll

65

Family

50

35

18

38

6

35

10

31

3

17

Patient & Family

17

12

4

8

2

12

5

16

2

12

6

6

2

4

-

--

2

6

l

6

143

100

48

100

17

100

31

100

17

Unknown

N

Faulty

Expectations

%

N

%

100

,j::..

00

49

slightly larger percentage (53%) did not know why they

were eligible for home care and a slightly smaller percentage (45%) did not know how services were paid.

The

biggest difference in respondent awareness was that 65%

of those who expected services that are not covered, were

"patient" respondents.

Needs for supportive services were perceived and

unmet as indicated by 83 responses from the study sample.

Some consumers perceived need for more than one supportive

service (Table 12).

The most prevalent need was perceived

for more visits (16.8%).

Other needs were housekeeping

(14.7%), transportation (11.9%), shopping (8.4%) and

psychological help (6.3%).

Discussion.

Stringent regulations regarding

criteria_ for visit reimbursement, limit the agency from

providing additional visits.

(It was observed that the

agency provided visits, free of charge, when needs were

urgent and patient did not meet the eligibility requirement for reimbursement.)

Housekeeping, transportation,

shopping and psychological help are also services for

which home health agencies are not reimbursed.

Studies show that lifestyle and needs are highly

related (40:153).

Living arrangements of patients were

cross tabulated with supportive services needs (Table 13).

Of those who needed more visits, 42 percent live alone.

Table 12

Supportive Service Needs

Questionnaire

Item #

Supportive Services Needed

#16

Transportation

#16

Psychological Help

#16

Number

Responses

Percent

of

Sample

Mean

Rating

Scores*

17

11.9

2.0

9

6.3

1.8

Housekeeping

21

14.7

1.9

#16

Shopping

12

8.4

1.7

#16

More visits

24

16.8

1.8

Total Services Needed

83

* Ratings by Management Adivisory Committee are rated on a scale of 1 to 5.

1 - - -

very acceptable

-

- - -

5

unacceptable

U1

0

Table 13

Relationship of Living Arrangement with Supportive Service Needs

Living

Arrangement

N

%

Needed

Transp.

Needed

Hskpg.

N

%

N

%

Needed

More

Visits

N

Needed

Psych.

Help

Needed

Shopping

%

N

%

N

%

Alone

37

26

8

47

9

43

10

42

2

22

6

50

Older

52

36

5

29

7

33

6

25

4

44

5

42

Younger

27

19

3

18

4

19

6

25

-

--

1

8

Deceased

23

16

1

4

1

5

2

8

3

33

4

3

0

143

100

17

100

21

100

24

100

9

100

12

100

Unknown

Total

U1

1-'

52

Those who lived alone also expressed the greatest

percentage of need for transportation (47%) and housekeeping {43%) and shopping (50%).

Age and sex were examined

for their relationship to needs.

frequencies.

Table 14 presents raw

Age and sex refer to the patient's charac-

teristics but we do not know whether patient and/or family

expressed the need, hence the data is of little value.

Although the sample numbers are small, they

follow patterns similar to those in studies reported by

Schutz; the greatest needs are expressed by sick elderly

without a social support system (lived alone)

(40:124).

Only 9 people expressed need for psychological

counseling, but one-third of these were from families

where the patient was deceased (Table 15).

A willingness to attend group family meetings was

interpreted as a consumer need.

Of those responding,

42.3 percent said they would attend meetings (Table 16),

and 54 percent of this group were the patients themselves (Table 17).

Discussion.

Underlying needs which motivated

respondents to agree to attend meetings could be

Psycho-social needs - Group support

Educational - to learn more about care of patient

Informational - to exchange ideas about common

problems

Table 14

Relationship of Age by Sex by Supportive Service Needs

Needed

Transportation

Needed

Housekeeping

Needed

Psychological

Help

Male

Female

Male

Male

Under 40

-

-

-

2

-

-

-

-

-

40 - 60

1

2

3

-

-

1

3

-

2

60 - 80

4

5

2

10

3

3

1

10

2

3

80+

1

4

1

3

1

1

3

7

1

3

Totals by Sex

6

11

6

15

4

5

7

17

5

7

Age

Female

Female

Needed

More

Visits

Male

Needed

Shopping

Female

Male Female

1

Totals f0r

Both Sexes

17

21

9

24

12

Ul

w

54

Table 15

Needed Psychological Counseling by

Living Arrangements

Living Arrangement

N

%

Needed

Psychological

Counseling

N

%

Alone

37

26

2

22.2

With Older Person

52

37

4

44.4

With Younger Person

27

19

Patient Deceased

23

16

3

33.3

4

2

Unknown

Total

143

100%

9

100%

Table 16

Interest in Attending Group Support Meetings

Questionnaire

Item

#18

Would attend group

support meetings

Number

Responses

Yes

97

41

Percentage N0

Response

42.3

47

Percentage Unde- Percentage RM~~n

Response cided Response S~o~~~

48.5

8

8.2

2.2

*Ratings done by Management Advisory Committee and rated on a scale of 1 to 5.

1

very acceptable

5

unacceptable

U1

(Jl

Table 17

Identification of Respondent Interested in Group Meetings

Would Attend Group Meetings

Respondent

%

N

% of Responses

N

Patient

70

49.0

22

53.7

Family

50

35

16

39

Patient and Family

17

11.9

Other

2

1.4

Unknown

4

2.8

Totals

143

100%

3

7.3

0

41

100%

Ul

~

57

I

Problem solving - to assist with problems

Although some dissatisfaction with services was

expressed and many needs were unfulfilled, an overall

positive attitude toward home health services in general

was indicated.

Responses to Item 15 showed that 96.7 per-

cent of those who responded agreed that the advantages of

receiving health care services at home outweighed the disadvantages while only 3.3 percent disagreed.

Part III.