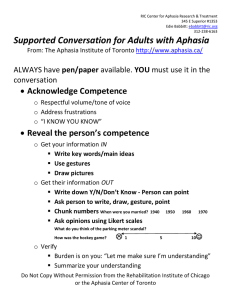

THE IMPACT OF SUPPORTED CONVERSATION STRATEGIES ON PERSONS WITH

advertisement