1 WHEN JUSTICE PROMOTES INJUSTICE: WHY MINORITY LEADERS WHO ACT

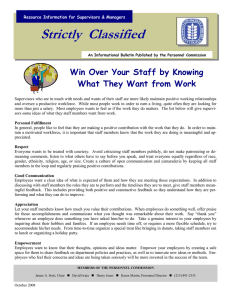

advertisement