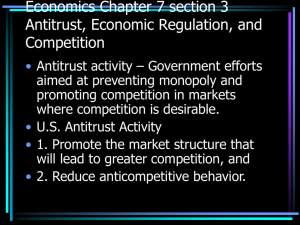

ANTITRUST AND THE COMPETITIVE STRUCTURE OF THE U.S. PULP By:

advertisement