Early Pentecostalism in India: the case of the Mukti... Dr. Arun W. Jones © 2007

advertisement

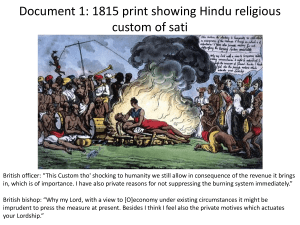

Early Pentecostalism in India: the case of the Mukti Mission Dr. Arun W. Jones © 2007 It seems to me that Pentecostalism is one of the most catholic Christian movements in the world today, the other being Roman Catholicism. Catholicity implies two very different, even contradictory things. One of them is universality: the church is catholic because it is found everywhere, and it is the same church that is found everywhere. But catholicity also implies diversity: the same church that is found everywhere is not everywhere the same. Each ethnic or national church has its own particularities and characteristics. For a number of reasons there is a tendency for observers both inside and outside Pentecostalism to notice and pay attention to its universal aspects, its intercultural and international connections. This afternoon, therefore, I would like to highlight the distinctive nature of one particular Pentecostal revival that occurred in India in 1905, and I want to look at one way in which this revival is rooted in the soil of Hindu religion and religiosity. The revival took place at the Mukti Mission in Kedgaon in southwestern India, a mission for girls and women that was operated by a very remarkable woman, Pandita Ramabai. Ramabai Dongre was born into a Brahmin family in southwest India in 1858.1 Her father, quite unusually for his times, insisted on his wife and daughters being educated. So Ramabai learned and memorized prodigious amounts of sacred Sanskrit texts in her childhood and teenage years. The experience of extreme deprivation and the loss of all of her family except her brother during a severe famine caused Ramabai to question the efficacy of her religion—the gods did not respond to religious rituals and privations as they were supposed to—and she converted first to a reform movement in Hinduism, the Brahmo Samaj, and then to Christianity. 1 A good biographical sketch of Pandita Ramabai’s life can be found in Robert Eric Frykenberg, “Pandita Ramabai Saraswati: A Biographical Introduction,” in Pandita Ramabai, Pandita Ramabai’s America, ed. Robert Eric Frykenberg, trans. Kshitija Gomes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 1-54. 1 At the same time, she became absorbed by the plight of Indian women, especially high caste widows who lived bound by social structures and customs in abject misery, and she dedicated her life to their advancement and liberation. In 1883 she went to England for further studies. From there she went in 1886 to America where she stayed for two years raising awareness and money for Indian women’s causes. Once back in India in 1889, she opened a home named “Sharada Sadan” (House of Learning) in Bombay for Brahmin widows, many of whom were mere children and who were shunned in their families because the deaths of their much older husbands had been attributed to the widows’ evil deeds in a previous life. The school was religiously neutral, which made it palatable to high caste Hindu families. The next year Ramabai moved the school to Pune due to the high cost of living in Bombay. Pune, however, was the bastion of conservative forces that disapproved highly of her amelioratory activities. Moreover, Ramabai experienced a religious awakening which led her to be more open about her own religious convictions. Girls at the Sharada Sadan in Pune were attracted to Ramabai’s religiosity, and rumors started to circulate that there were conversions occurring. Indeed, after some time baptisms did occur, although at the insistence of the girls and against Ramabai’s preference. Indian support for Ramabai plummeted over the next few years,2 and she was never again influential on the national stage for reform and liberation, although she continued to work until her death in 1922 to change the conditions of women, especially widows, in her beloved land. Once the break was made with strict Hindu society, the Sharada Sadan became an “avowedly and explicitly Christian” institution.3 From 1896 a severe famine once again ravaged 2 3 Frykenberg, 34. Frykenberg, 36. 2 the country, and Ramabai “launched herself into a massive rescue and relief campaign.”4 She rescued famine orphans and brought them to Pune, but then was forced to move them to the nottoo-distant village of Kedgaon where she had purchased some land. What was needed, Ramabai discovered, was not simply food and shelter: given their depravation and degradation, the girls had to be taught a whole new way of life, a completely new culture. “This massive rescue operation profoundly altered Ramabai’s work.”5 It gave birth in Kedgaon to Mukti Sadan and the Mukti Mission, a large institution for girls rescued from the famine. The word Mukti is a synonym for Moksha, which is literally the escape from the horrible repeated cycle of life and death. Moksha is what all Hindus long for; it is salvation, it is also freedom and liberty; it is release from bondage to the misery of life; it is escape from materiality into the bliss of immaterial nothingness. Thus the Mukti Mission was a place for liberty, release, salvation. In 1905 Ramabai and the girls in the Mukti Sadan experienced a pentecostal revival. News of revivals in Wales and in northeast India had intensified Ramabai’s longstanding yearning for a powerful religious experience.6 Thirty young women were meeting daily to pray for spiritual power when the Revival came upon them. On the morning of June 29 Minnie Abrams, a missionary working at the Mukti Mission “was awakened at 3.30, by one of the senior girls saying, ‘Come over and rejoice with us, J. has received the Holy Spirit. I saw the fire, ran across the room for a pail of water and was about to pour it on her, when I discovered that she was not on fire.’ When Miss Abrams arrived, all the girls of that compound were on their knees weeping, praying, and confessing their sins.”7 The next evening, during the prayer meeting held by Ramabai (and while she was expounding John 8, which contains the story of the woman 4 Frykenberg, 38. Frykenberg, 41. 6 The following account is taken from Helen S. Dyer, Revival in India: A Report of the 1905-1906 Revival (Akola, Maharashtra: Alliance Publications, 1987, reprint of 1907), 32 ff. 7 Dyer, 32. 5 3 caught in adultery), we are told that “the Holy Spirit descended with power, and all the girls began to pray aloud so that she had to cease talking. Little children, middle-sized girls, and young women, wept bitterly and confessed their sins. Some few saw visions and experienced the power of God, and things that are too deep to be described. Two little girls had the spirit of prayer poured on them in such torrents that they continued to pray for hours. They were transformed with heavenly light shining on their faces.”8 We are told by another source that the girls called the revival “a baptism of fire. They say that when the Holy Spirit comes upon them it is almost unbearable—the burning within. Afterwards they are transformed, their faces light up with joy, their mouths are filled with praise.”9 Ramabai confessed that she herself had inexplicable ecstatic experiences: “a consciousness of the Holy Spirit as a burning flame within her and times when, alone in prayer, she involuntarily uttered some sentences in Hebrew.”10 The revival was marked by confession of sins, prayers, much singing, dancing, clapping, glossolalia, and sensations of being consumed by fire. In my paper, which is much longer, I trace three themes as they develop from Ramabai’s Hindu background to the 1905 Revival. I have time however to make only one observation that on the one the one hand is rather obvious, and on the other hand layered with complexity. The observation is that some of the reports about the revival speak about the girls or women (and later others) feeling as though they were actually on fire. In India, to this day, the rhetoric of fire and widows is explosive material indeed. The practice of sati, where a widow dies on her husband’s funeral pyre, or on a separate pyre soon afterwards, had been outlawed in British India 8 Dyer, 33. Quoted in Dyer, 34. 10 Frykenberg, 51. 9 4 in 1829.11 However, it continued to be discussed and at times practiced. Ramabai herself alludes to the practice occasionally in her writings, and not always in the same way. In The High Caste Hindu Woman, written in America, Ramabai describes the desperate plight of upper caste women and especially widows, and spends a number of pages describing sati. On the one hand, she calls it a “terrible custom,” a “horrid rite,”12 an “inhuman custom.”13 On the other hand, she explains why it could in good conscience have been practiced,14 how abolishing it has not solved the terrible problems faced by Indian widows,15 and how in fact at times sati or suicide may be a fate preferable to the life of misery currently faced by Hindu widows.16 So Ramabai ends up giving qualified support to what she calls a terrible and inhuman custom. Her views of sati, then, are highly complex and contain a degree of ambivalence. There are two aspects of Sati that are relevant to this paper. The first is that in theory, however it may have worked in practice, sati was a means for attaining moksha (mukti) or liberation/salvation. As Ramabai put it, “The priests and their allies, pictured heaven in the most beautiful colors and described various enjoyments so vividly that the poor widow became madly impatient to get to the blessed place in company with her departed husband. Not only was the woman assured of her getting into heaven by this sublime act, [notice the adjective “sublime”] but also that by this great sacrifice she would secure salvation to herself and her husband, and to their families to the seventh generation. Be they ever so sinful, they would surely attain the highest bliss in heaven, and prosperity on earth. Who would not sacrifice herself if she were sure of such a result to herself and her loved ones?”17 Thus being consumed by the fire of one’s 11 Cf. “Sati” in Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., vol. 12 (New York: Thomson Gale, 2005), 8129-31. High Caste Hindu Woman, 74. 13 High Caste Hindu Woman, 78. 14 High Caste Hindu Woman, 77. 15 High Caste Hindu Woman, 81 ff. 16 High Caste Hindu Woman, 86, 90. 17 High Caste Hindu Woman, 75. 12 5 husband or “lord,” was a means to salvation: to mukti. Is it simply a coincidence that women, some of them widows, at Mukti Sadan, the Home of Salvation, experienced being literally burned by the purifying fire of the Holy Spirit, giving them a taste of salvation? There is a second aspect of Sati that is relevant to our discussion. In popular tradition, the virtuous wife who immolates herself, the sati, on the funeral pyre is not simply throwing her body on burning flames. Rather, the fire which is “sat,” meaning being itself, truth, and virtue, is within the woman. In some lines of thinking, the “sat” or fire comes into the woman as a god or demon or spirit and penetrates her body when she cries out at the funeral pyre, “I am going to eat fire,” “I am going to follow my husband,” “I am going to be a sati,” “Praised be such and such a god, such and such a goddess!” She is possessed by the god or spirit, her body (and the bodies of those witnessing the rite) shakes convulsively and she is spirited away by the god.18 There is another line of thinking that believes that the woman already possesses “sat” because she is virtuous. Since she possesses the sat she actually dies not by the fire of the funeral pyre but by “an instantaneous death, devoid of either burns to the body or physical suffering, by ‘selfcombustion.’ Fire is not the agent of the satis’ death, but rather the essence of their being.”19 In both these lines of thinking, what we have are deeply held religious beliefs, corroborated even by some experiences, of women who are possessed by the fire of being, of truth, of virtue, even of God, and are transported to moksha or mukti or salvation, by burning. They even talk of “agnisnan,” or fire bath: which is the literal meaning of baptism of fire, a phrase used by some of the girls at the Mukti Mission to describe being possessed by the Holy Spirit. I do not think that the girls and other Christians in the revival of 1905 who experienced the Holy Spirit as fire burning within them were thinking of themselves as “satis.” What I do 18 Catherine Weinberger-Thomas, Ashes of Immortality: Widow-Burning in India, trans. Jeffrey Mehlman and David Gordon White (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 22. 19 Catherine Weinberger-Thomas, Ashes of Immortality, 23. 6 think is happening is that the Indian Christians who participated in the Pentecostal revival of 1905 were drawing on local as well as universal (including missionary and biblical) stores of religious knowledge and experience, and that the local understandings combined with the universal ones to shape the way they experienced the revival. 7