Progress and Opportunities, Five Years On: Challenges and Recommendations for Montreux Document

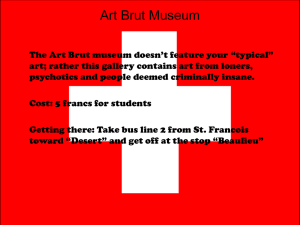

advertisement