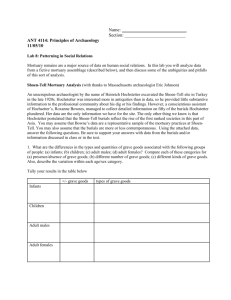

ANALYSIS OF 23SN777: SLOW DRIP ROCK SHELTER A Thesis by

advertisement