Document 14912738

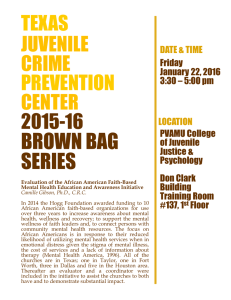

advertisement