CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE MARKING

advertisement

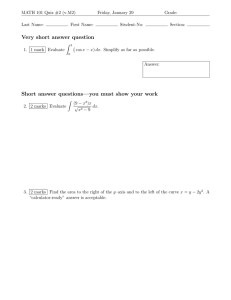

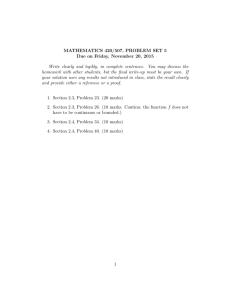

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE MARKING Tlt~E An abstract submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Mollie Doctrow January 1984 0 ' The Abstract of Mollie Doctrow is approved: Marvin Harden Ci M!y Marsh - Tom Fricano, Chair California State University, Northridge i i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with a deeper understanding and appreciation of my family, friends, and teachers that I submit this paper. For their sincere and careful guidance I thank my graduate committee, Tom Fricano, Marvin Harden, and Cindy Marsh. A special thanks to my parents, Flo and Jerry Doctrow; my grandfather, Mr. Sam Silverstein; and my friend, Ron Fisher, for their love, support, and encouragement. ii i TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i i i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . v INTRODUCTION 1 DEVELOPMENT 3 TECHNIQUE 6 CONCLUSION 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure ~ 1 Swamp Song . . 2 Merlin Make Me Wise 10 3 Dead End . . . 11 4 Broken Fence 12 5 Memory of a Garden . . 13 6 Keeper of the Gate 14 7 Air . . . 15 8 Cold Chill 16 9 Daydream in Blue . 17 Thicket 18 10 9 ...... . v . ~_- - ABSTRACT MARKING TIME by Mollie Doctrow Master of Arts in Art INTRODUCTION In the November 5, 1983, issue of Artweek, Jeff Kelley wrote, 11 To call something a 'mark' is to empty it of reference other than the reference to itself ... l This could be a profound statement, but I suspect it is very near the opposite, shallow and simplistic. It would be a profound statement depending upon Kelley's metaphysics. Kelley is saying that a mark is just a mark. statement about reality. This makes a Things are just what they are. But Kelley is really taking a formalistic viewpoint about 1Jeff Kelley, "The Inquiring Mark, 11 Artweek Vol. 14, No. 37. November 5, 1983, page 5. l 2 what constitutes a work of art--three marks on the left, two on the right, and you have a picture. Japanese art has a long tradition of using marks to represent objects and processes. With simple, subtle strokes, the Japanese artist deftly captures the flight of a hummingbird, the galloping horse, grasses bending in the wind. Curiously enough, the Japanese artist strives for a concrete and realistic art. But realistic does not mean factual realism in the Western sense of the word. But, rather, it is realistic to the reality of immediate experience, which goes beyond perceptual qualities. 2 The Japanese artist seeks to capture the "essence" or "life force 11 of an object or experience. 3 Mark making for me began as a response to what constitutes space, tiny particles. Space isn't something "filled-in"; rather, space is composed of matter--alive and intelligent. A "squiggly 11 dot denoted matter. Marks proved to be the most direct means to capture an idea or represent something. With the barest of means, mark making manifests the internal an9 the external. It is a visual shorthand with the potential to signify, represent, conjure up associations, and arouse emotions. 2 charles A. Moore, ed., The Jatanese Mind--Essentials of Ja anese Philoso h and CultureHonolulu: East-West Center Press, 1967 , p. 12. 3 Makoto Ueda, Literary and Art Theories in Japan (Cleveland, Ohio: The Press of Western Reserve University, 1967), p. 135. -~ DEVELOPMENT A two-day visit to a swamp provided the necessary, specific, physical impetus to develop the series Time. 11 11 Marking The swamp left a haunting memory of overgrown, tangled vines, twisted branches, dried-up leaves, bits of clothing and paper. I sought to capture the rushing wind, the crackling leaves, the dancing light, the traces of humanity, all interweaving with each other, moving through time. Specific marks were used to represent various ele- ments. Layering marks added the element of time and the means to portray the simultaneity of several 11 events. 11 A love-hate relationship with the swamp developed. The dense, dark foliage was engulfing. of death, loathing and fear. It aroused feelings And yet, simultaneously, the crisp, fresh air injected a sparkling life to the myriad of details, beckoning surrender. In its wake solitude and peace remained, coexisting with fear of the unknown. Color, and the application and immediacy of certain marks, were used to express the emotional aspects of the experience. Collaged elements were added to heighten the physical presence of the pieces and suggest more explicitly the human involvement. Eleven prints comprise the It begins with the 11 Swamp Song. 11 3 11 Marking Time 11 series. The piece is composed 4 entirely of layered marks. A large brushstroke (rhythm)~ various "scraggly" marks (fragments), a "net-like" drip (tangled vines), sticks, the "squiggly" dot and printed objects (screens, papers, washers) comprise the repertoire of marks used in the prints. With the "Swamp Song," "Merlin Make Me Wise," "Stagnant View," and "Dead End," I sought to capture the deep, dark mystery of nature overgrown. "Broken Fence," "Memory of a Garden," "Keeper of the Gate," and "Air" are primarily about the rhythm and variety of the swamp experience. They range in color and mood from the light, atmospheric color or "Air" to the bright, dancing color of "Memory of a Garden." Curiously enough, along the banks of the swamp domesticated red geraniums grew beside vivid pink, wild sweet peas and gold mustard flowers. In "Broken Fence" the all-over gold pat- tern of the marks is emphasized. This is intended to create a more compressed confrontation of the experience and heighten the metaphysical associations. 11 Cold Chill, 11 "Daydream in Blue," and 11 Thicket" more aggressively seek to capture mood, place, and movement. Collage is used more liberally. larger, the marks are bolder. The color patches are The clarity of colors in the "Cold Chill," the coolness of the purples, the clusters of collaged papers and tangled marks evoke fragments caught up in a gust of wind. The 11 Chill" is that moment of recog- nition when, with goose bumps, the world is a cold place, p • 5 and be i ng warm i s all that matters . The a real thicket than an emotional thicket. 11 Th i c ke t 11 i s 1 e s s It is a place where memory and reality are tangled up, going around and around. 11 0aydream in Blue 11 is that patch of cerulean blue peaking through the foliage, dancing about as the trees bend and sway. TECHNIQUE All of the work was printed from a collograph base plate. The base plate, made primarily with gel medium, carried the main image. This image was enhanced either by printing a secondary plate or with monotype techniques. This involved placing acetate over the print, drawing marks with a grease pencil, reversing the acetate, applying ink over the pencil marks, and running through the press. Most of the prints have been "run through" the press at least six times. The base plate was often printed three times in order to achieve the desired density. ink was applied with small rollers. Thick The goal was to over- print as necessary in order to build up an actual paint surface on the paper. Different papers required varying amounts of ink to achieve this effect. Arches, Rives BFK, and German Etching were used in this series. German Etch- ing required the least amount of runs to achieve a rich, dense surface. The physical presence of the work was an important consideration. It was necessary that the work exude "abjectness" rather than "picture-ness." My intent was to capture the physical and metaphysical experience of the swamp rather than represent a picture of it. 6 CONCLUSION The swamp served a secondary purpose. It became a perceptual metaphor for the way in which space is structured. Intertwining branches formed a three-dimensional model for things to hang-on, move-through, and behind. In "Thicket," transparent purple printed over black weaves in and out of hot, intense gold patches and black and red jagged marks. This was intended to suggest fragmented memories intertwining with the present. Mark making is not without reference to something beyond itself. instant in time. At the very least a mark represents an This logically implies a maker, a sur- face, materials, etc. But further, a strategically placed mark, sensitively executed, hqs the potential to capture a specific feeling, arouse emotions, refer to itself and beyond itself. 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY Hofstader, Albert. Agony and Epitaph. Braziller Inc., 1970. New York: George Kahler, Erich. The True, the Good, and the Beautiful. Ohio State University Press, 1960. Kelley, Jeff. 11 The Inquiring Mark. 11 Artweek Vol. J.i, No. 37. November 5, 1983, p. 5. Mathieu, Georges. From the Abstract to the Possible. Paris: Editions Du Cercle D'Art Contemporain, 1960. Moore, Charles A. The Japanese Mind--Essentials of Japanese Philosolhy and Culture. Honolulu: East-West Center Press, 967. Rose, Bernice. Jackson Pollock: Drawing into Painting. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1980. Seitz, William. Mark Tobey. Modern Art, 1962. Schmied, Wieland. 1966. Tobey. New York: The Museum of New York: Henry N. Abrams, Inc., Ueda, Makoto. Literary and Art Theories in Japan. Cleveland, Ohio: The Press of Western Reserve University, 1967. 8 9 Figure 1. Swamp Song (26x38 11 ) )· ·, 10 .·. Figure 2 . Merlin Make Me Wise (18 ~ x32") l2 \ Figure 4. Broken Fence (26x38") 14 Figure 6. Keeper of the Gate (26x38 11 ) 15 Figure 7. Air (26x38 11 ) l6 j· Figure 8. Cold Chill (30x3l 11 ) 17 Figure 9. Daydream in Blue (30x31 11 )