CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THROUGH CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

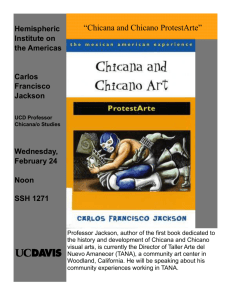

advertisement