Event structure influences language production: Evidence from

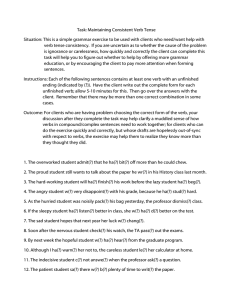

advertisement