Liquidated Damages & Mitigation: A Construction Contract Thesis

advertisement

LIQUIDATED AND ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD)

AND REQUIREMENTS OF MITIGATION

YONG MEI LEE

UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA

PSZ 19: 16 (Pind. 1/97)

UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA

BORANG PENGESAHAN STATUS TESIS ♦

JUDUL: LIQUIDATED AND ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD) AND

REQUIREMENTS OF MITIGATION

SESI PENGAJIAN : 2005 / 2006

Saya

YONG MEI LEE ___________________________

(HURUF BESAR)

mengaku membenarkan tesis (PSM / Sarjana / Doktor Falsafah)* ini disimpan di

Perpustakaan Universiti Teknologi Malaysia dengan syarat-syarat kegunaan seperti

berikut:

1. Tesis adalah hakmilik Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

2. Perpustakaan Universiti Teknologi Malaysia dibenarkan membuat salinan untuk

tujuan pengajian sahaja.

3. Perpustakaan dibenarkan membuat salinan tesis ini sebagai bahan pertukaran

antara institusi pengajian tinggi.

4. ** Sila tandakan (9)

9

SULIT

(Mengandungi maklumat yang berdarjah

keselamatan atau kepentingan Malaysia seperti yang

termaktub di dalam AKTA RAHSIA RASMI 1972)

TERHAD

(Mengandungi maklumat TERHAD yand telah

Ditentukan oleh oprganisasi/ badan di mana

Penyelidikan dijalankana)

TIDAK TERHAD

Disahkan oleh

__________________________________________

(TANDATANGAN PENULIS)

Alamat Tetap:

22, Jalan Saga SD8/2E,

Bandar Sri Damansara,

52200 Kuala Lumpur.

Tarikh: ____________________

CATATAN:

__________________________________________________

(TANDATANGAN PENYELIA)

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rosli Abdul Rashid

Nama Penyelia

Tarikh: ______________________

* Potong yang tidak berkenaan.

** Jika tesis ini SULIT atau TERHAD, sila lampirkan surat daripada pihak

berkuasa/organisasi berkenaan dengan menyatakan sekali sebab dan

tempoh tesis ini perlu dikelaskan sebagai SULIT atau TERHAD.

Tesis dimaksudkan sebagai tesis bagi Ijazah Doktor Falsafah dan

Sarjana secara penyelidikan, atau disertasi bagi pengajian secara kerja

kursus dan penyelidikan, atau Laporan Projek Sarjana Muda (PSM).

“We hereby declare that we have read this thesis and in our opinion this thesis is

sufficient in terms of scope and quality for the award of the degree of

Master of Science in Construction Contract Management.”

Signature

: .................................................................

Name of Supervisor I : .................................................................

Date

: .................................................................

Signature

: .................................................................

Name of Supervisor II : .................................................................

Date

: .................................................................

LIQUIDATED AND ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD)

AND REQUIREMENTS OF MITIGATION

YONG MEI LEE

A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the

requirements for the award of the degree of

Master of Science in Construction Contract Management

Faculty of Built Environment

Universiti Teknologi Malaysia

MARCH, 2006

ii

DECLARATION

I declare that this thesis entitled “Liquidated and Ascertained Damages (LAD) And

Requirements of Mitigation” is the result of my own research except as cited in the

references. The thesis has not been accepted for any degree and is not concurrently

submitted in candidature of any other degree.

Signature

: .................................................................

Name

: .................................................................

Date

: .................................................................

iii

Specially dedicated to my family for your love and support

“With love and appreciation”

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express my thankfulness to those who have helped me in

completing this thesis. First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere

appreciation to my supervisor, Associate Professor Dr. Rosli Abdul Rashid, for his

encouragement, support, guidance and dedication in assisting me to succeed in

writing out this thesis.

Special thanks to En. Jamaludin Yaakob for his concerns, comments and

professional advices. Besides that, I would also like to acknowledge Associate

Professional Dr. Maizon Hashim, En. Norazam Othman for their support and

motivation.

My appreciation also goes to all my classmates, Nor Jalilah Idris, Ling Tek

Lee, Dennis Oon Soon Lee; my friends Sze Nee, Voon Chiet and Wan Siang for their

great support, opinion and willingness to share their knowledge towards the

completion of my research.

Finally, I would like to extend my truthful appreciation to all my family

members, especially my father, the late Yong Weng Lok and my beloved mother,

Mdm. Kok Nyok Moi for her love and support.

Yong Mei Lee

March, 2006

v

ABSTRACT

When a project is late in completion due to contractor’s fault, the employer is

entitled to a contractual remedy by enforcing the Liquidated and Ascertained

Damages (LAD) provisions.

However, contractors often seek to challenge the

enforceability of LAD by alleging that the employers suffer no loss and that they are

under a duty to mitigate their losses. Therefore, the objectives of the research are to

determine the requirements of mitigation and the extent of the employer’s duty to

mitigate his losses when enforcing his right under the LAD clause. The objectives of

this research are achieved by analysing relevant laws governing LAD and mitigation.

The governing laws include relevant statutes, judicial decisions, and the Contracts

Act 1950. The research found that although the requirements is silent in standard

forms of contract, an employer is bound to comply with the requirements of

mitigation in enforcing LAD by taking all reasonable steps to mitigate his losses.

Furthermore, employer’s duty to mitigate his losses is governed by the principles of

mitigation. He is only bound to take all reasonable steps in order to comply with the

requirements and does not has to embark on hazardous or uncertain courses of action

that will cause him incur substantial expense or inconvenience, damage his

reputation, or breach any contracts, in order to mitigate. The reasonable actions to

mitigate will be determined on a case-to-case basis.

In short, this research is

expected to grab the attention of employers in enforcing LAD, so that they can

safeguard their claims.

vi

ABSTRAK

Apabila sesuatu projek mengalami kelewatan disebabkan kegagalan

kontraktor, majikan akan menuntut gantirugi tertentu dengan mengenakan klausa

Ganti Rugi Tertentu (Liquidated and Ascertained Damages, LAD).

Walau

bagaimanapun, kontraktor sentiasa mencabar pengenaan klausa tersebut dengan

menyatakan bahawa pihak klien tidak mengalami kerugian dan mereka adalah

dikehendaki mengurangkan kerugian yang dialami. Oleh yang demikian, kajian ini

dijalankan untuk mengenalpasti keperluan pengurangan kerugian dan sejauh

manakah klien perlu bertindak untuk mengurangkan kerugian yang dialami semasa

mengenakan haknya dibawah klausa LAD.

Objektif kajian ini dicapai dengan

menganalisa undang-undang yang mengawal LAD dan pengurangan.

Undang-

undang kawalan yang berkaitan termasuklah statut, keputusan mahkamah dan Akta

Kontrak 1950.

Kajian ini mendapati walaupun kehendak tersebut adalah tidak

dinyatakan, klien adalah terikat untuk mematuhi kehendak pengurangan semasa

mengenakan LAD dengan mengambil langkah-langkah yang munasabah bagi

mengurangkan kerugiannya.

Tambahan pula, hak klien untuk mengurangkan

kerugiannya adalah dikawal oleh dasar pengurangan. Klien hanya terikat untuk

mengambil langkah-langkah munasabah bagi mematuhi kehendak tersebut dan tidak

perlu bertindak sehingga menyebabkannya mengalami kerugian lanjutan atau

ketidaksenangan, menjejaskan reputasinya, atau memungkiri mana-mana kontrak

dalam

usaha

mengurangkan

kerugian.

Kemunasabahan

tindakan

mengurangkan kerugian ditentukan berdasarkan kes-kes yang tersendiri.

untuk

Secara

ringkasnya, kajian ini dijangka akan menarik perhatian klien semasa mengenakan

LAD, supaya mereka dapat mempertahankan tuntutan mereka.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER

TITLE

PAGE

TITLE

i

DECLARATION

ii

DEDICATION

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

iv

ABSTRACT

v

ABSTRAK

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

vii

LIST OF CASES

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

xvi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

xvii

LIST OF APPENDICES

xviii

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1

Background Of Study

1

1.2

Problem Statement

6

1.3

Objectives Of The Study

8

1.4

Scope And Limitations Of The Study

8

1.5

Significance Of The Study

9

1.6

Research Methodology

9

1.6.1 Stage 1: Identifying Research Issue

10

1.6.2

Stage 2: Literature Review

10

1.6.3

Stage 3: Data And Information Collection

10

1.6.4

Stage 4: Research Analysis

11

viii

1.6.5

Stage 5: Conclusion And Recommendations 11

1.7

Research Flow Chart

12

1.8

Conclusion

13

1.8.1

Chapter 1: Introduction

13

1.8.2

Chapter 2: Liquidated And Ascertained

Damages (LAD)

13

1.8.3

Chapter 3: Mitigation

14

1.8.4

Chapter 4: Requirements of Mitigation and

The Extent of Mitigation in Enforcing

LAD Provisions

1.8.5

14

Chapter 5: Conclusion And

Recommendations

14

CHAPTER 2 LIQUIDATED AND ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD)

2.1

Introduction

15

2.2

Breach Of Contract

17

2.2.1

19

2.3

2.4

2.5

Remedies For Breach Of Contract

Damages

20

2.3.1

General Principles of Damages

21

2.3.2

Types Of Damages

22

2.3.3 Statutory Provisions

24

2.3.4 Recovery Of Damages

26

2.3.4.1 Remoteness Of Damage

27

2.3.4.2 Measure Of Damage

29

2.3.5 Proof Of Damages

30

Liquidated And Ascertained Damages (LAD)

32

2.4.1

Express Contractual Provisions

32

2.4.2

Definition Of LAD

34

2.4.3

Merit Of The LAD Provision

35

2.4.4

Advantages Of LAD Provision

37

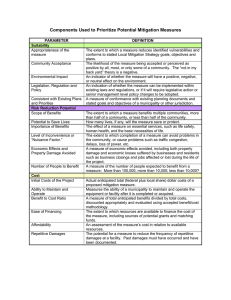

Component Costs Of LAD

38

2.5.1

39

Loss Of Income

ix

2.6

2.5.2

Financing Loss

40

2.5.3

Business Disruption Loss

40

2.5.4 Management Costs

41

2.5.5 Professional Fees

41

LAD And Penalties

41

2.6.1 Distinction Between LAD And Penalties

42

2.6.2

Pleading Cases In Distinguishing LAD

And Penalties

2.7

44

Liquidated And Ascertained Damages:

The Malaysian Position

46

2.7.1 Applicable Statutory Provision

46

2.7.2 Interpretation Of Section 75 Of

Contracts Act 1950

2.7.3

Recovery Of Liquidated And

Ascertained Damages (LAD)

2.8

47

Conclusion

51

53

CHAPTER 3 MITIGATION

3.1

Introduction

54

3.2

Definition Of Mitigation

55

3.3

General Rules And Principles Of Mitigation

55

3.4

Mitigation In Malaysian Position

57

3.5

The Duty To Mitigate

59

3.6

Limitation Of Mitigation Upon Recovery

Of Damages

63

3.7

Mitigation In Building Contracts

64

3.8

Significance Aspects In Relation To Mitigation

65

3.9

Conclusion

67

x

CHAPTER 4 REQUIREMENTS OF MITIGATION AND THE EXTENT

OF MITIGATION IN ENFORCING LAD PROVISIONS

4.1

Introduction

4.2

Requirements Of Mitigation in Enforcing LAD

Provisions

70

4.2.1 Malaysian Law

70

4.2.2

English Law

71

4.2.3

English Commercial Law

74

4.2.4

Requirements Of Mitigation In Building

Contracts

4.3

75

To What Extent That Employer Has To Mitigate

His Losses In Enforcing LAD Provisions

78

4.3.1 The Extent In Loss Mitigation

78

4.3.2

4.3.3

4.4

69

Reasonableness In Taking The Duty

To Mitigate

79

Bottom Line Of Mitigation

80

Conclusion

81

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1

Introduction

83

5.2

Research’s Findings

83

5.2.1

Objective 1: To Determine The

Requirements Of Mitigation In Enforcing

The LAD Provisions in Construction

Contracts

5.2.2

84

Objective 2: To Determine The Extent That

Employer Has To Mitigate His Losses In

Enforcing LAD Provisions

85

5.3

Research’s Constraints

86

5.4

Suggestions For Further Research

86

5.5

Conclusion

87

xi

REFERENCES

89

APPENDICES

A

General Procedure in Recovery of Liquidated Damages

96

B

Clause 40 of the JKR Forms 203A (Rev 10/83)

99

C

Clause 22.0 of the PAM 1998 Forms

100

D

Clause 26 of the CIDB Form (2000 Edition)

102

E

Section 74-76 of Contracts Act 1950

104

F

Section 3, 5 of Civil Law Act 1956

110

G

Case 1: Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr Jasawant

Singh a/l Jagat Singh [2003] 5 MLJ 116

114

H

Case 2: Payzu Ltd. v Saunders [1919] 2 K.B. 581

123

I

Case 3: Selva Kumar a/l Murugiah v

Thiaragajah a/l Retnasamy [1955] 1 MLJ 817

127

xii

LIST OF CASES

CASE

PAGE

AMEV-UDC Finance Ltd. v Austin [1986] 162 CLR 170, 193

………15

Balfour Beatty Construction (Scotland) Ltd v Scottish Power plc

[1994] 71 BLR 20

………………………………………………28

Ban Hong Joo Mine Ltd. v Chen & Yap Ltd [1969] 2 MLJ 83

………19

Bhai Panna Singh v Bhai Arjun Singh [AIR 1929 PC 179] ......47, 48, 49, 53

Boyo v Lambeth London Borough Council [1994] ICR 727

Brace v Clader [1895] 2 Q.B. 253

………77

………………………………………60

British Westinghouse Electric Co. v Underground Electric

Railway Co. of London [1912] AC 673

Chiam Keng v Wan Min [1924] 5 FMSLR 4

………...…….19, 56, 78

………………………..4

Choo Yin Loo v Visuvalingam Pillay [1930] 7 FMSLR 135

Chou Choon Neoh v Spottiswoode [1869] 1 Ky. 216

Chulas v Kolson [1867] Leic.462

……4, 19

………………73

………………………………………73

Chung Syn Kheng Electrical Co Bhd. v Regional Construction

Sdn Bhd. [1987] 2 MLJ 763 ……………………………………4, 49

Dennis v Sennyah [1963] MLJ 95

..……………………………………..23

Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd.

[1915] AC 79

..……………………………………....4, 16, 42

Fateh Chand v Balkrishan Dass AIR 1963 supreme court 1405

Frank & Collingwood Ltd v. Gates [1983] 1 Con LR 21

.……….5

…..…………..22

Gebruder Metel Mann GmbH & Co. KG v NBR (London) Ltd.

[1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 614

..……………………………………..62

xiii

Government of Malaysia v Thelma Fernandez [1967] 1 MLJ 194

............5

Government of Pakistan v Seng Peng Sawmills Sdn Bhd.

[1979] 1 MLJ 219

……………………………………………..66

Hadley v Baxendale [1854] 9 Ex 341 ………4, 24, 26, 27, 28, 30, 50, 51, 52

Hong Leong Co Ltd v Pearlson Enterprise Ltd (No 2 )

[1968] 1 MLJ 262

………..…………………………....23, 57, 58

Hopkins v Norcross plc [1993] 1 All ER 565)

..……………………77

Hua Khiow Steamship Co. Ltd. v Chop Guan Hin

[1930] 1 MC 175, 1 JLR 33 .………………………..…………….4

Hutchinson v Harris [1978] 10 BLR 19

……………………………..65

Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr. Jaswant Singh A/L Jagat Singh

[2003] 5 MLJ 116

.……………………...5, 76, 77, 82, 84, 87, 88

Kabatasan Timber Extraction Co. v Chong Fah Shing

[1969] 2 MLJ 6

..………………………………………….5, 59

Kemble v Farren [1829] 6 Bing 141

...…………………………....44

Khoo Hooi Leong v Khoo Chong Yeok [1930] A. C. 346

...……………73

Khoo Tiang Bee v Tan Beng Guat [1877] 1 Ky. 423

……………...73

Kilbourne v Tan Tiang Guee [1972] 2 MLJ 94

...……………………23

Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Birmingham City Council [1996] 4 All ER 733 …77

Kon Thean Soong v Tan Eng Nam [1982] 1 MLJ 323

..…………….75

Kueh Sing Khay v Lim Boon Chuan [1950] SCR 23

...……………67

Larut Matang Supermarket Sdn. Bhd. v Liew Fook Yung

[1995] 1 MLJ 379

..…………………………………………….17

Law v Redditch Local Board [1892] 1 QB 127

...……………………43

Linggi Plantation Ltd v Jagatheesan [1972] 1 MLJ 89 ...4, 17, 47, 48, 49, 53

Malayan Credit Ltd. v Mohammed Kassim [1965] 2 MLJ 134

...……..5

Maredelanto Compania Naviera SA v Bergbau-Handel GmbH;

'The Mihalis Angelos' [1970] 3 WLR 601

……………………...77

Morello Sdn Bhd v Jaques (International) Sdn Bhd.

[1995] 1 MLJ 577 (also reported at [1995] 2 CLJ 23,

[1995] 1 AR 873 and [1995] 1 MAC 153)

……………………..67

Pacific Electrical Co Ltd v Seng Hup Electrical Co (S) Pte Ltd.

[1978] 1 MLJ 162

……………………………………………..66

Paradine v Jane [1647] Aleyn 26

………………………………………1

xiv

Pasuma Pharmacal Corp v McAlister & Co Ltd.

[1965] 1 MLJ 221

………………………………………65, 79, 81

Payzu Ltd. v Saunders [1919] 2 K.B. 581 ……...60, 61, 62, 66, 79, 81, 84, 87

Penang Port Commission v Kanawagi s/o Seperumaniam

[1996] 3 MLJ 427

………………………………………………76

Pilkington v Wood [1953] 2 Ch 770; [1953] 3 WLR 522 …..66, 68, 80, 82, 85

Public Works Commissioner v Hills [1906] AC 368

Robinson v Harman [1848] 1 Ex 850

...…………….45

…………………………...19, 28

Rockingham Country v Luten Bridge Co. [1929] US Ct of App

……….65

SEA Housing Corporation Sdn. Bhd. v Lee Poh Choo

[1982] 1 MLJ 324

……………………………………....30

Selva Kumar a/l Murugiah v Thiaragajah a/l Retnasamy

[1955] 1 MLJ 817

……………………3, 24, 50, 52, 53, 87

Selvanayagam v University of the West Indies

[1983] 1 WLR 585

…………………………………..64, 81

Smith Construction Co. Ltd. v Phit Kirivata [1955] MLJ 8 ………………19

Song Toh Chu v Chan Kiat Neo [1973] 2 MLJ 206 ………………………17

SS Maniam v The State of Perak [1975] MLJ 75

………………..4, 47, 48

Stanor Electric Ltd v R Mansell Ltd. [1988] CILL 399

………………44

Syarikat Batu Sinar Sdn. Bhd. & Ors v UMBC Finance Bhd.

& Ors. [1990] 3 MLJ 468

………………………………………73

Syed Jaafar bin Syed Ibrahim v Maju Mehar Singh Travel &

Tours Sdn. Bhd. [1999] 4 MLJ 413 ………………………………31

Tan Hock Chan v Kho Teck Seng [1980] 1 MLJ 308

………………19

Tansa Enterprise Sdn Bhd v Temenang Engineering Sdn Bhd.

[1994] 2 MLJ 353

………………………………………………58

Techno Land Improvements Ltd v British Leyland (UK) Ltd

[1979] EGD 519

………………………………………76, 77, 84

Tham Cheow Toh v Associated Metal Smelters Ltd [1972] 1 MLJ 171 ..28, 28

Toeh Kee Keong v Tambun mining Co. Ltd [1968] 1 MLJ 39

………28

T & S Contractors Ltd v Architectural Design Associated QBD

(Official Referee's Business) 16 October 1992

………………77

Victoria (Laundry Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd

[1949] 2 KB 528

………………………………………………26

xv

Wearne Brothers (M) Ltd v Jackson [1966] 2 MLJ 155 ...4, 24, 25, 48, 49, 53

Wee Wood Industries Sdn. Bhd. v Guannex Leasing Sdn. Bhd

[1990] 2 CLR 1060

……………………………………………….4

West v Versil Ltd & Ors Court of Appeal (Civil Division)

………………77

Westwood v Secretary of State for Employment [1985] AC 20

………77

William Tompkinson & Sons Ltd. v Parochial Church Council of

St. Michael [1990] 6 Const. LJ 319 ………………………………64

Woon Hoe Kan & Sons Sdn. Bhd. v Bandar Raya Development Bhd.

[1972] 1 MLJ 75

………………………………………………17

WT Malouf Pty Ltd v Brinds Ltd [1981] 52 FLR 442

………………..4

Yerkey v Jones [1940] 63 CLR 649 ………………………………………19

xvi

LIST OF FIGURES

FUGURE NO.

TITLE

PAGE

1.7

Research Flow Chart

12

xvii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AC

-

Appeal Cases

AIR

-

All India Reports

Bing

-

Bingham Reports

BLR

-

British Law Reports

Con LR

-

Construction Law Reports

Ex

-

Exchequer Reports

FMSLR

-

Federated Malay States Law Reports

ICE

-

Institute of Civil Engineering

JLR

-

Johore Law Reports

KB (or QB)

-

King’s (or Queen’s) Bench

LAD

-

Liquidated and Ascertained Damages

Lloyd’s Rep

-

Lloyd’s List Law Reports

MC

-

Malayan Cases

MLJ

-

Malayan Law Journal

PAM

-

Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia

PC

-

Privy Council

PCC

-

Privy Council Cases

PWD

-

Public Work Department

SCR

-

Supreme Court Reports

SIA

-

Singapore Institute of Architects

SO

-

Superintending Officer

UTM

-

Universiti Teknologi Malaysia

WLR

-

Weekly Law Reports

xviii

LIST OF APPENDICES

APPENDIX

TITLE

PAGE

A

General Procedure in Recovery of Liquidated Damages

96

B

Clause 40 of the JKR Forms 203A (Rev 10/83)

99

C

Clause 22.0 of the PAM 1998 Forms

100

D

Clause 26 of the CIDB Form (2000 Edition)

102

E

Section 74-76 of Contracts Act 1950

104

F

Section 3, 5 of Civil Law Act 1956

110

G

Case 1: Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr Jasawant

Singh a/l Jagat Singh [2003] 5 MLJ 116

114

H

Case 2: Payzu Ltd. v Saunders [1919] 2 K.B. 581

123

I

Case 3: Selva Kumar a/l Murugiah v

Thiaragajah a/l Retnasamy [1955] 1 MLJ 817

127

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

Background of Study

A contract is an agreement enforceable by law. 1 When two or more persons

enter into a contract, their intention is normally to carry out the terms of contract as

promised. 2 As a general principle, once a party enters into a contract, he must perform his obligations strictly according to the terms of contract. 3 He is liable to answer for any of the obligations, which he has failed to discharge and it is no defence

to an action for incomplete performance that the party has done everything that can

be reasonably undertaken if the end result falls short of that required of the contract. 4

There are only two parties to a building contract: the employer and the contractor but due to the customary divisions of duties within the building process, several other persons are named. 5 Some of these are professional advisers to the em1

Section 2(h) of Contracts Act 1950.

Alsagoff, Syed Ahamad. (2003). Principles of the Law of Contract in Malaysia. Malyaisa: Malaysia

Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.1

3

Chow, Kok Fong. (1988). An Outline of the Law and Practice of Construction Contract Claims. Singapore: Longman Singapore Publishers Pte. Ltd., pp.27

4

Paradine v Jane [1647] Aleyn 26

5

Turner, D.F. (1971). Building Contracts: A Practical Guide. London: George Godwin Ltd., pp.9

2

2

ployer, who are also given defined responsibilities and powers under the contract,

some of which may be quasi-judicial. 6 A breach of contract is essentially a non performance of a contractual obligation under conditions for which no legal excuse for

the non performance exists. 7 The ordinary remedy for breach of contract is an action

for damages; the innocent party is entitled to claim for a financial amount, which

would compensate him for the loss incurred as a result of the breach committed by

the other party. In the example of late completion, the usual redress afforded the

employer would be to award him liquidated damages calculated according to a rate

stipulated in the contract. 8 In exceptional cases, where a breach takes on a very serious nature so that it adversely affects some fundamental aspect of the contract, the

innocent party may under common law, bring the contract to the end. 9

Liquidated damages may as a provision in a contract, and therefore agreed

between the parties to the contract at the time if entering into it, which aims to determine in advance the extent of the liability for some future, specified breach. 10

Construction contracts frequently contain a “liquidated damages” clause in favour of

the owner. This typical liquidated damages clause provides that if the contractor

fails to complete the work by the agreed completion date, he will be required to pay

the owner a stipulated amount for each day thereafter until completion. 11

For example, clause 40 12 of PWD Forms 203A (Rev 10/83), and clause 22 of

PAM 98 13 provides a provision of Damages for Non-completion. Briefly, the provi-

6

Ibid.

Chow, Kok Fong. (1988). An Outline of the Law and Practice of Construction Contract Claims. Singapore: Longman Singapore Publishers Pte. Ltd., pp.28

8

Ibid, pp.29

9

Ibid.

10

Turner, D.F. (1971). Building Contracts: A Practical Guide. London: George Godwin Ltd., pp.17

11

Kenny, P. (2001, March). Liquidated Damages: how much of a threat can they be? Heavy construction News. Toronto: Mar 2001 vol.45. Iss.3. Pg.32. URL:http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did37477610&sid-8&Fmt-3&clientld.21690&RQT-309&VName-PQD

12

If the Contractor fails to complete the Works by the “Date for Completion” stated in the Appendix

or within any extended time under Clause 43 hereof and the S.O. certificates in writing that in his

opinion the same ought reasonably so to have been completed the Contractor shall pay or allow the

Government a sum calculated at the rates stated in the Appendix as Liquidated and Ascertained Damages for the period during which the said Works shall so remain and have remained incomplete and

the S.O. may deduct such damages from any monies due to the Contractor.

7

3

sion indicates that in the event of late completion, the contractor shall pay to the employer the LAD a specified amount per day of delay until the completion date. The

employer may deduct such sum from any monies payable to the Contractor under

this Contract. In addition, the LAD is considered as the actual loss that will be suffered in breach f contract and the contractor agrees to pay the said sum without the

need of proving damages by the employer.

Statutory provision for liquidated damages in Malaysia is found in Section 75

of the Contracts Act 1950. 14

“When a contract has been broken, if a sum is named in the contract as the

amount to be paid in case of such breach, or if the contract contains any

other stipulation by way of penalty, the party complaining of the breach is entitled, whether or not actual damage or loss is proved to have been caused

thereby, to receive from the party who has broken the contact reasonable

compensation not exceeding the amount so named or, as the case may be, the

penalty stipulated for”.

The Federal Court in Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy 15 held that the employer is required to prove his actual loss suffered in accordance with the general principles of proof of damages. The Federal Court, in interpreting Section 75 held that the plaintiff who is claiming for actual damages in an

action for breach of contract must still prove the actual damages or reasonable com13

22.1 If the Contractor fails to complete the Works by the Date for Completion of within any extended time fixed under Clause 23.0 or sub-clause 32.1 (iii) and the Architect certifies in writing that

in his opinion the same ought reasonably so to have been completed, then the Contractor shall pay to

the Employer a sum calculated at the rate stated in the Appendix as Liquidated and Ascertained Damages (LAD) for the Date for Completion or any extended date where applicable to the date of Practical

Completion. The Employer may deduct such sum as a debt from any monies due or to become due to

the Contractor under this Contract.

22.2

The Liquidated and Ascertained Damages stated in the Appendix is to be deemed to be as the

actual loss which the Employer will suffer in the event that the contractor as in breach of the Clause

thereof. The Contractor by entering into this Contract agrees to pay to the Employer the said

amount(s) if the same become due without the need of the Employer to prove his actual damage or

loss.

14

Sundra Rajoo. (1999). The Malaysian Standard Form of Building Contract (The PAM 1998

FORM). 2nd ed. Kuala Lumpur; Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.195

15

[1995] 2 MLJ 817

4

pensation in accordance with the settled principles in the English landmark case of

Hadley v Baxendale. 16 Any failure to prove such damages will result in the refusal

of the court to award such damages. The Contracts Act s75 provides an instance in

which Malaysian law departs significantly from the line of English common law. 17

Under common law, a liquidated damages clause must comply with the ‘penalty’ principle establish by Lord Dunedin in the landmark case of Dunlop Pneumatic

Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd. 18 that:

“The essence of liquidated damages is a genuine covenanted pre-estimate of

loss.”

What is meant by the term ‘genuine pre-estimate’ was further explained in

WT Malouf Pty Ltd v Brinds Ltd 19 as:

“A genuine pre-estimate means a pre-estimate which is objectively of that

character: that is to say, a figure which may properly be called so in the light

of the contract and the inherent circumstances. It will not be enough merely

that the parties honestly believed it to be so.”

The court in Malaysia have concluded that the distinction between liquidated

damages and penalties does not apply, the situation being governed by section 75 of

the Contracts Act which has been held to have erased this distinction. 20

16

[1854] 9 Ex 341

Robinson, N.M., et.al. (1996). Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia 2nd ed. Singapore: the

Butterworth Group of Companies., pp.244

18

[1915] AC 79

19

[1981] 52 FLR 442

20

See e.g. Choo Yin Loo v SK Visuvalingam Pillay [1930] 7 FMSLR 135, The Hua Khiow Steamship

Co. Ltd. v Chop Guan Hin [1930] 1 MC 175, 1 JLR 33; SS Maniam v The State of Perak [1957] MLJ

75; Wearne Bros (M) Ltd. v Jackson [1966] 2 MLJ 155; Linggi Plantation Ltd v Jagatheesan [1972]

1 MLJ 89, [1971] 2 PCC 749, reversing [1969] 2 MLJ 253, which in turn reversed [1967] 1 MLJ 177;

and Wee Wood Industries Sdn. Bhd. v Guannex Leasing Sdn. Bhd. [1990] 2 CLR 1060. See also the

Bruneian Case of Chung Syn Kheng Electrical Co Bhd. v Regional Construction Sdn Bhd. [1987] 2

MLJ 763 which, however, is not, with respect, wholly unambiguous. Cf Chiam Keng v Wan Min

17

5

In addition, there is a general duty requiring that reasonable steps to be taken

to mitigate losses flowing a breach particularly in the case of anticipatory breach. 21

The party who has failed to mitigate the losses cannot later recover any such loss

flowing from his neglect. 22 This is a long established principle applied in Kabatasan

Timber Extraction Co. v Chong Fah Shing. 23 The Federal Court held that, it was the

duty of the respondent to take reasonable steps to mitigate the damages caused by the

appellant when he failed to deliver logs to the mill but left them some 500 feet away.

This principle also applied in Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr. Jaswant Singh a/l

Jagat Singh. 24 The respondent counterclaimed for loss of rental income against appellant’s claim for the balance sum due for the completed building works was dismissed by the High Court due to respondent’s failure to show that he had taken all

reasonable steps to mitigate his damage.

Construction contracting is extremely time sensitive and timely completion of

a project is frequently seen as major criteria of a project success. 25 Owners lose opportunity and profits waiting for completion of late projects. 26 Hence, a liquidated

damages provision provides a straight forward method of calculating damages recoverable by an owner in the event of late completion. However, the recent position

seems to put more burdens to employer in his effort to impose LAD. The recent

case, Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr. Jaswant Singh A/L Jagat Singh 27 , employer

is now liable to take mitigation in enforcing LAD although it is silent in the provision

of LAD in the forms of contract. Failure in taking mitigation will cause the employer fail in recovering the LAD.

[1924] 5 FMSLR 4 at 14. But cf Malayan Credit Ltd. v Mohammed Kassim [1965] 2 MLJ 134 and

Government of Malaysia v Thelma Fernandez [1967] 1 MLJ 194. Reference may be also be made to

the Indian Supreme Court decision of Fateh Chand v Balkrishan Dass AIR 1963 supreme court 1405.

21

Vohrah, B. and Wu, Min Aun. (2003). The Commercial Law of Malaysia. Malaysia: Pearson Malaysia Sdn. Bhd., pp.179

22

Ibid.

23

[1969] 2 MLJ 6

24

[2003] 5 MLJ 116

25

Allen, P.E.(Jan, 1995). The Estimation of Construction Contract Liquidated Damages.

URL:http://www.library.findlaw.com.civil.remedies/damages/liquidated.damages./html

26

Ibid.

27

Supra.

6

As a result, the court is now applying the principle of mitigation in awarding

LAD and the employer should be prudent while imposing LAD, whereby they will

have to make sure that they fulfil the requirements of mitigation by taking reasonable

steps to mitigate his losses and damages upon the breach of contract by the contractor.

1.2

Problem Statement

Each of the standard form of contract provides for payment of an agreed sum

by the contractor when completion of work is not within the stipulated time. The

payment is known as liquidated and ascertained damages. The amount is usually recorded in the appendix to the form of a contract. 28 Liquidated damages are a sum,

which represents a genuine pre-estimate of the loss caused by the breach, that is, of

what is needed to put the plaintiff into as good a position as if the contract had been

performed. 29

The liquidated damages provisions in the usual standard forms of contract for

construction work is to stipulate a rate for each day of delay in completing the works,

clearly links the severity of delay to the quantum of damages payable. 30 Most standard forms of construction contract are drafted to permit the parties to fix the damages payable for late completion in advance. When these damages are a genuine preestimate of the loss likely to be suffered or a lesser sum, they can rightly be termed

as liquidated damages. 31

28

Ashworth, A. (2001). Contractual Procedures in the Construction Industry. 4th ed. England: Pearson Education Limited., pp.32

29

Burrows, A. S. (1987). Remedies for Torts and Breach of Contract. London: Butterworth & Co.

(Publishers) Ltd., pp.283

30

Chow, Kok Fong. (1988). An Outline of the Law and Practice of Construction Contract Claims.

Singapore: Longman Singapore Publishers Pte. Ltd., pp.159

31

Eggleston, B. (1997). Liquidated Damages and Extension of Time in Construction Contracts. 2nd ed.

London: Blackwell Science Ltd., pp.4

7

Most construction contracts provide a contractual mechanism, which allows

the employer to deduct liquidated damages from amounts due to the contractor. 32

For examples, in PAM 98 33 (clause 22), PWD 203A 34 (Clause 40), and CIDB 35

(Clause 26) provide a provision of Damages and Non-completion to enable the employer to recover their damages in the event of late completion by contractor. However, contractors often seek to challenge the enforceability of Liquidated Damages

clause 36 , which they consider that it has been wrongly deducted and alleged that employer actually suffered no loss in the event of delay and fails to mitigate his losses

in the event of breach. 37

Such challenges may cause an uncertainty to the employer, as it is not expressed in the provisions. Further, the employers may not be aware that they are obligated to take mitigation in enforcing LAD. Thus, this matter may give raise to

some queries, such as, whether the employer is bound to mitigate his loss in the event

of enforcing the LAD. Since all standard forms of contract are silent about the duty

to mitigate loss, then what are the rules that may override the provisions of LAD in

the contract? In addition, if the employer is really bound to comply with the mitigation rules, then what are the circumstances does the employer could take mitigation

and to what extent they should act to mitigate his losses?

Regarding the quantum of damages, whether the employer is entitled only for

the loss that he managed to mitigate, or he is totally not entitled to recover his loss if

he failed in taking the duty of mitigation. Furthermore, it may be doubted that what

are the circumstances that the employer is considered has conducted the said duty

and how does the tribunal make the decision on this matter.

32

Steve, Chan. (2004). Lecture 4: Duty to Mitigate, Constructive Acceleration, Challenges to Liquidated Damages. Bullet-Proof EOTs-with Particular reference to PWD/JKR standard Forms of Contract. 27 July, 2004. Kuala Lumpur: James R Knowles (M) Snd. Bhd., pp.17

33

Agreement and Conditions of Building Contract

34

Standard Form of Contract to be used where Bills of Quantities Form Part of The Contract

35

Standard Form of Contract for Building works (2000 Edition)

36

Steve, Chan. (2004). Lecture 4: Duty to Mitigate, Constructive Acceleration, Challenges to Liquidated Damages. Bullet-Proof EOTs-with Particular reference to PWD/JKR standard Forms of Contract. 27 July, 2004. Kuala Lumpur: James R Knowles (M) Snd. Bhd., pp.18

37

Ibid.

8

In short, whether the duty to mitigate should have a controlling influence on

the conduct of the innocent / injured party, or whether it is merely a method of assessing the recoverable loss and how does the mitigation may effect the enforcement

of LAD by the employer? As a result, it is important to investigate the actual position of employer in enforcing the LAD.

1.3

Objectives of the Study

The objectives of the study are:

1.

To determine the requirements of mitigation in enforcing the LAD

provisions in Construction Contracts.

2.

To determine the extent that employer has to mitigate his losses in enforcing LAD provisions.

1.4

Scope and Limitations of the Study

This research will be focused on following matter:-

1.

The provision of Liquidated and Ascertained Damages in the standard

forms of contract used in Malaysia, namely, JKR 203A, PAM98, and

CIDB 2000.

2.

Court cases related to the issue particularly Malaysian cases. Reference is also made to cases in other countries such as United Kingdom,

Brunei, Singapore, Australia, and Hong Kong.

9

1.5

Significance of the Study

The provision of LAD is provided in most standard form of building contracts in favour of the employer to recover their damages or losses due to delay in

completion. However, the contractor often seek to challenge the enforcement of

LAD is challenged by the contractor on certain grounds as before discussed. Such

challenge put the employer in an uncertain position while enforcing LAD although

the compensation for non-completion has pre-agreed by the contracting parties and

stipulated in the contract.

Therefore, this study is expected to unfold the queries that arise in the event

of enforcing LAD in relation to mitigation. Thus, an employer will be aware of their

obligations, rights, and duties in the event of recovering his damages or losses. In

short, the finding of the study could be used as guidance to the employer and putting

them in a better position in enforcing LAD. Finally, it is believed that the result will

also be capable to resolve disputes in relation to LAD in the construction industry.

1.6

Research Methodology

Briefly, the research process will be divided into five (5) stages:

a.

Identifying the research issue,

b.

Literature review,

c.

Data and information collection,

d.

Research analysis,

e.

Conclusion and recommendations

10

1.6.1

Stage 1: Identifying Research Issue

Identifying the research issue is the initial stage of the whole research. To

identify the issue, firstly, it involves reading on variety sources of published materials, such as journals, articles, seminar papers, previous research papers or other related research papers, newspapers, magazines, and electronic resources as well

through the World Wide Web and online e-databases from University of Technology

Malaysia, UTM library’s website. 38

1.6.2

Stage 2: Literature Review

Literature review is the second stage of the research. Literature review will

be involved the collection of documents which from secondary data for the research,

such as books, journals, newspapers. 39 Indeed, published resources like books, journals, varies standard form of contract, and related statutory are the most helpful in

this literature review stage. Besides this, reported court cases from different sources

like Malayan Law Journal, Australia Law Report, and Building Law Reports will be

referred.

1.6.3

Stage 3: Data and Information Collection

Third stage of this research is data and information collection stage. This is

an important stage towards achieving the objectives. This stage will be begun just

38

39

http://www.psz.utm.my

Blaxter, L., et al. (1996). How to research. Buckingham; Open University Press., pp.109

11

after the previous two stages are completed. The further action is to collect the relevant information based on the secondary data from the published resources and carry

out case studies. Lexis-Nexis database is the main source in getting the related cases.

The system provides cases based on different sources of law reports available, such

as Appeal Cases Report, All England Report, Building Law Report, King’s Bench

Report, Singapore Law Report and other common jurisdictions.

1.6.4

Stage 4: Research Analysis

In this stage, it is able to determine whether the stated objectives has been

achieved or vice versa. Different types of analysis will be carried out according to

the requirements of the objectives. It is important in conducting case study in the

way to identify the trends and developments in the issue that is to be studied.

1.6.5

Stage 5: Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion and recommendations is the final stage of the research. In this

stage, the findings would able to show the result of the research. A conclusion need

to be drawn in-line with the objectives of the research. At the same time, some appropriate recommendations related to the problems may be made for a better solution

in relation to the said problem, or for further research purposes.

12

13

1.8

Conclusion

Briefly, this research is related to the issues on principles of mitigation, and

Liquidated and Ascertained Damages (LAD) in building contracts. The report will

be divided into five (5) chapters.

1.8.1

Chapter 1: Introduction

The first chapter is an introduction to the whole research and consisting of a

few sub topics. The first sub topic is background of the study; followed by problem

statement, that influence such research to be carried out. Subsequence is the objectives of the research that stated the aims of the study; the significance of the research

as to overcome certain problems in the industry; scope and limitations to the research

and finally is the research methodology that to be used during the process of research.

1.8.2

Chapter 2: Liquidated and Ascertained Damages (LAD)

Briefly, this chapter will be covered by a few important subtopics, such as

introduction, definition of the term, LAD and LD, principle of LAD, LAD in the Malaysian position and finally the issues or cases in relation to the enforceability of

LAD in the event of breach of contract.

14

1.8.3

Chapter 3: Mitigation

This chapter will discuss the definition, theories, rules, and principles of mitigation. Besides that, the function of the principle applied in damages as remedy in

the event of breach of contract will also be discussed. Related cases will be incorporated in the explanation for getting a better understanding of the terms and its application.

1.8.4

Chapter 4: Requirements of Mitigation and The Extent of Mitigation in

Enforcing LAD Provisions

This chapter is the essential part of the whole report. The significant task is

to obtain the research’s findings, namely the requirements of mitigation, and to what

extent the employer has to mitigate his losses in enforcing LAD provisions.

1.8.5

Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations

This chapter is the final part of the whole report and is considered the conclusion chapter. Briefly, this chapter includes the summary on the research findings,

conclusion and recommendations and suggestions for further research.

CHAPTER 2

LIQUIDATED AND

ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD)

CHAPTER 2

LIQUIDATED AND ASCERTAINED DAMAGES (LAD)

2.1

Introduction

The parties to a contract may themselves specify in that contract an amount

which is payable to the plaintiff in the event of breach, such clauses are known as

liquidated or agreed damages clauses 1 Liquidated damages, synonymous with the

term Liquidated and Ascertained Damages and the abbreviation ‘LAD’ remain a

remedy most commonly encountered consequence of non-completion. 2

When the contractor is unable to complete the works by the original date for

completion set in the contract or by any new date fixed by the contract administrator

and the cause or causes of delay does not entitle the contractor to any valid extension

of time under the contract, he is guilty of breaching the contract. 3 A liquidated

damages clause ‘makes for greater certainty by allowing the parties to determine

more precisely their rights and liabilities consequent upon breach or termination’. 4

1

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.450

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Commencement and

Administration. . Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.501

3

Ibid.

4

AMEV-UDC Finance Ltd. v Austin [1986] 162 CLR 170, 193

2

16

In many projects, where time is the essence of construction, the owner and

the contractor agree under the contract that if the contractor fails to complete the

project by the stipulated date, it is finally liable to the owner for a pre-agreed sum for

each day beyond the specified completion date that it takes the contractor to finish

the work. 5 When liquidated damages are agreed in this way, the employer’s only

remedy for late completion is a sum not exceeding the specified liquidated damages

amount and the employer does not have the option to claim unliquidated damages. 6

In English Law, the courts will have to decide if they are liquidated damages

or a form of penalty. 7

The rules against penalties renders void a clause which

requires payment of a sum which is extravagant or unconscionable having regard to

the greatest loss which could be suffered by the plaintiff following the breach of

contract to which the sum relates. 8 If the amount is found to be a penalty then the

employer can only recover damages to the extent that they are proved. In addition,

the burden of proving that a stipulated sum is a penalty and not liquidated damages in

such situations rests with the contractor. 9 Whether a stipulated sum is liquidated

damages or a penalty depends upon the intention of the parties, but the Court have

laid down certain guiding rules. 10

However, the distinction between damages and a penalty does not apply in

Malaysia by virtue of Section 75 of the Contracts Act, 1950 as both are dealt in the

same manner. 11

5

Section 75 of the Contracts Act provides an instance in which

Fisk, E.R. (2004). Construction Project Administration. 7th Ed. New Jersey; Prentice Hall., pp.580

Martin, R. In What Circumstances Does An Employer Have The Right To Levy Liquidated

Damages? James R Knowles (M) Sdn. Bhd. URL:

www.jrk.com.sg/ARTICLES/employerliqdamages.htm

7

Vohrah, B. and Wu, Min Aun. (2003). The Commercial Law of Malaysia. Malaysia: Pearson

Malaysia Sdn. Bhd., pp.178

8

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.450

9

Martin, R. In What Circumstances Does An Employer Have The Right To Levy Liquidated

Damages? James R Knowles (M) Sdn. Bhd. URL:

www.jrk.com.sg/ARTICLES/employerliqdamages.htm

10

see Lord Dunedin in Dunlop Tyre Co. Ltd. v New Garage & Motor Co. Ltd. [1915] AC 78

11

Martin, R. In What Circumstances Does An Employer Have The Right To Levy Liquidated

Damages? James R Knowles (M) Sdn. Bhd. URL:

www.jrk.com.sg/ARTICLES/employerliqdamages.htm

6

17

Malaysia law departs significantly from the line of English common law. 12

Compensation is apparently recoverable up to the limit of the stipulated figure if that

was a genuine pre-estimate and is considered by the court to be reasonable. 13 There

is no support for the view that a plaintiff may recover a genuine pre-estimate without

proof of any actual loss. 14 Thus, it is important for the employer to ensure that the

amount stipulated as liquidated damages is a reasonable calculation of the likely loss

to the employer and not an exaggerated sum since the purpose is only to provide the

employer with reasonable compensation. 15

In short, this chapter addresses the consequences of non-completion

focussing on the issue of ‘LAD’, as a remedy to be compensated by the nonbreaching party flow from a breach of contract.

2.2

Breach of Contract

A breach of contract occurs where a party does not perform her or his

obligations in accordance with the terms of the contract. 16 Eggleston, B. (1997) in

his book Liquidated Damages and Extensions of Time in Construction Contract 17

mentioned that every breach of contract carries with the potential for dispute and

breach of contract in the construction industry are common either by the employer or

12

Robinson, N. M., et al. (1996). Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia. 2nd ed. Singapore:

The Butterworth Group of Companies., pp.244. See also in Linggi Plantations Ltd v Jagatheesan

[1972] 1 MLJ 89.

13

see Larut Matang Supermarket Sdn. Bhd. v Liew Fook Yung [1995] 1 MLJ 379, Song Toh Chu v

Chan Kiat Neo [1973] 2 MLJ 206, Woon Hoe Kan & Sons Sdn. Bhd. v Bandar Raya Development

Bhd. [1972] 1 MLJ 75.

14

Dato’ Visu sinnadurai. (1987). The Law of Contract in Malaysia and Singapore: Cases and

Commentary. 2nd ed. Singapore: Butterworth & Co. (Asia) Pte Ltd., pp. 704.

15

Martin, R. In What Circumstances Does An Employer Have The Right To Levy Liquidated

Damages? James R Knowles (M) Sdn. Bhd. URL:

www.jrk.com.sg/ARTICLES/employerliqdamages.htm

16

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.333

17

Eggleston, B. (1997). Liquidated Damages and Extensions of Time in Construction Contract. 2nd ed.

London: Blackwell Science Ltd.

18

by the contractor because of lack or neglect in the performance of his obligations

under the contract. 18

When the employer is in breach by way of interference or prevention arising

from late supply of information, failure to give full possession of the site and the like,

the result for the contractor is delay, disruption, and involvement in loss and expense

or extra cost. 19 On the other hand, the contractor’s breaches of contract are most

commonly due to failure to proceed with due diligence, failure to meet specified

standard and failure to complete the project on time. 20

The employer’s position is significantly different from the contractor’s.

Whereas the contractor has a financial remedy for numerous and various breaches,

the employer has his for only one breach of common occurrence – failure by the

contractor to complete on time. 21 The financial effects of the employer’s breach on

the contractor can rarely by estimated in advance because of the involvement of subcontractors, but the financial effects of the contractor’s late completion can usually

be estimated with some certainty. 22

Consequently, in order to resolve these disputes, most standard forms of

construction contract are drafted to permit the parties to fix the damages payable for

late completion in advance and containing clauses that detailing with the procedures

to be applied in the event of breach. 23

18

Eggleston, B. (1997). Liquidated Damages and Extensions of Time in Construction Contract. 2nd ed.

London: Blackwell Science Ltd., pp.3

19

Ibid.

20

Ibid.

21

Ibid, pp.4

22

Ibid.

23

Ibid.

19

2.2.1

Remedies for Breach of Contract

A breach of contract occurs when one party fails to perform an obligation

under the terms of the contract. 24 An award of damages is the primary remedy for

any breach of contract. 25 Contract law uses various remedies to repair the damage

caused by a breach of contract. 26 The purpose of contract damages is to compensate

the plaintiff for loss caused by a breach of contract. 27 An award of damages is to

place the victim of the breach, so far as an award of damages can, in the position he

would have been in if the contract had been performed. 28 When there is a breach of

contract, the party who is not in default may claim one or more of the remedies,

namely rescission of contract, damages, specific performance, and injunction. 29

Rescission is a form of relief which, in appropriate circumstances, is available

to victims of the following vitiating factors: mistake, misrepresentation, duress,

undue influence, unconscionable dealing, breach of fiduciary duty, and under the rule

in Yerkey v Jones [1940] 63 CLR 649. 30 The purpose and effect f rescission, as

traditionally understood, is to set aside the contract and restore the parties to their

original pre-contractual positions. 31 Section 40 of the Contracts Act stated that when

a party to a contract has refused to perform / disable himself from performing his

promise, then the promise may put on end. 32

24

Ashworth, A. (2001). Contractual Procedures in the Construction Industry. 4th ed. England:

Pearson Education Limited., pp.31

25

Ibid

26

Damages and otherRemedies for Breach of Contract.

URL:http://www.law.washington.edu/courses/ramasastry/A50k/handouts/remedies.html

27

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.234

28

Robinson v Harman [1848] 1 Exch 850. See to similar effect Viscount Haldane LC in British

Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co Ltd v underground Electric Railways Co of London Ltd

[1912] AC 673 at 689: ‘The first is that, as far as possible, he who has proved a breach of a bargain to

supply what he had contracted to get is to be placed, as far as money can do it, in as good a situation

as if the contract had been performed. The fundamental basis is thus compensation for pecuniary loss

naturally flowing from the breach.’

29

Vohrah, B. and Wu, Min Aun. (2003). The Commercial Law of Malaysia. 2nd ed. Selangor: Pearson

Malaysia Sdn. Bhd., pp.176

30

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.605

31

Ibid.

32

In Choo Yin Loo v Visuvalingam Pillay [1930] 7 FMSLR 135, the court affirmed the view that

section 40 enacted English law on the subject. See also in Ban Hong Joo Mine Ltd. v Chen & Yap

Ltd [1969] 2 MLJ 83, Tan Hock Chan v Kho Teck Seng [1980] 1 MLJ 308, and Smith Construction

Co. Ltd. v Phit Kirivata [1955] MLJ 8

20

Specific performance is an order of the court compelling the defendant to

perform his or her part of the contract.33 The courts will enforce a party to do what it

has contracted to do, in preference to awarding damages to the aggrieved party. 34

Specific performance will only be granted where damages are an inadequate

remedy. 35 However, specific performance will not be granted where the contracts

requiring constant supervision, or the contracts involves personal services or lack of

mutuality at the time of the judgment. 36

Oxford dictionary of law stated that injunction is a remedy in the form of a

court order addressed to a particular person that either prohibits him from doing or

continuing to do a certain act or orders him to carry out a certain act. In other words,

an injunction may be granted to restrain a breach of negative stipulation (a promise

not to do something) in the contract. 37 In addition, the Specific Relief Act, defines

injunction as a remedy is classed in the Part III as ‘Preventive Relief’ and there are

various types of injunction, namely, Prohibitory Injunction, Interlocutory Injunction,

Quia Timet Injunction, Mareva Injunction, Anton Piller order and Erinford

Injunction. 38

2.3

Damages

Whenever a party (the defendant) breaches a contract, the other party (the

plaintiff) will be entitled to an award of damages as monetary compensation for the

breach. 39 Damages are normally awarded based on a basis of placing the innocent

33

Duxbury, R. (1991). Contract in A Nutshell. London: Sweet & Maxwell., pp.101

Ashworth, A. (2001). Contractual Procedures in the Construction Industry. 4th ed. England:

Pearson Education Limited., pp.33

35

Duxbury, R. (1991). Contract in A Nutshell. London: Sweet & Maxwell., pp.101

36

Ibid.

37

Ibid, pp.102

38

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.217-222

39

Paterson, J. et.al. (2005). Principles of Contract Law, 2nd ed. Sydney: Lawbook Co., pp.411

34

21

party in the same financial position as if the contract had been properly performed. 40

In addition, whether rightly or wrongly, under the English law, damages for breach

of contract are designed to compensate the innocent party for the breach, to make

good the actual loss, within certain parameters rather than to punish the guilty party.

2.3.1

General Principles of Damages

Damages are granted to the innocent party for the damage, loss or injury he

has suffered for a breach of contract. 41 In addition, there are two further points need

to be considered in relation to the general approach to damages. These are:

a.

If the parties have expressly agreed and stipulated in their contract or

agreement a particular remedy for the breach complained or, due

effect will be given to this means of redress provided, it is not

repugnant to the law; and

b.

Once the innocent party has selected a particular remedy to pursue

and has manifested his choice to the defaulting party; who in reliance

upon the manifestation has taken any action, the choice is binding and

will bar recourse to any other alternative.

Syed Ahmad Alsagoff (2003) states that the law grants the damages to a party

as monetary compensation for the damage, loss or injury suffered through a breach

of contract. He added that, the court will not award compensation to the plaintiff for

all the losses suffered because of breach, provided he has fulfil certain qualifications

required. The requirements are related to remoteness of damages and the plaintiff

40

Duxbury, R. (1991). Contract in A Nutshell. London: Sweet & Maxwell., pp.102

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.200

41

22

must shows that it was the defendant’s breach that caused him to suffer the said loss.

The both requirements will be discussed in further detail in subtopic 2.3.4.

2.3.2

Types of Damages

Damages can be classified into a few types 42 as following:

a)

General Damages

These are damages, which the law presumes to have resulted from the act of

the defaulting party (defendant) and which need not be specially pleaded.

They are recoverable as compensation for such loss as the parties may

reasonably foresee as a natural consequence of the breach or act complained

of. Examples include damages for pain, inconvenience, disappointment, etc:

Frank & Collingwood Ltd v. Gates. 43

b)

Special Damages

Special damages are damages of a kind which the law will not presume in the

innocent party’s (plaintiff’s) favour, but which must be specially pleaded and

proved at the trial or arbitration hearing, e.g. loss of profit, interest on money,

etc.

42

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.209

43

[1983] 1 Con LR 21

23

c)

Nominal Damages

Nominal damages are damages awarded where, although there is a technical

breach resulting in the contravention of a right but it results in no real loss to

the innocent party.

Examples include trespass 44 , failure of claimant to

mitigate loss 45 , or where the plaintiff is better off as a result of the breach.

d)

Substantial Damages

Substantial damages represent compensation that is given for loss actually

sustained by the aggrieved party.

These are in essence, pecuniary

compensation intended to put the aggrieved party (plaintiff) in the position he

would have enjoyed had the contract been performed. These represent the

classic example of damages based on the ‘compensatory’ principle.

e)

Exemplary Damages

Exemplary damages are vindictive or punitive and are awarded so as to

punish a defaulting party (defendant). Exemplary damages consist of a sum

awarded which is far greater than the pecuniary loss suffered by the innocent

party. These damages are awarded only in exceptional circumstances, eg.

defamation, breach of promise to marry etc: Dennis v Sennyah. 46

f)

Unliquidated Damages

Unliquidated damages are unascertained damages that need to be proved.

These damages are dependent on the circumstances of the case.

44

Kilbourne v Tan Tiang Guee [1972] 2 MLJ 94

Hong Leong Co. Ltd. v Pearlson Enterprises Ltd (No.2) [1968] 1 MLJ 262

46

[1963] MLJ 95

45

24

g)

Liquidated Damages

These are damages agreed between the parties at the time of contracting and

stated in the contract as the damages payable in the event of a specified

breach, usually that is of late completion. The sum must be a genuine preestimate of loss likely to be caused by the breach or lesser sum. Liquidated

damages cannot be recovered simpliciter: Wearne Brothers (M) Ltd. v

Jackson. 47 These damages are covered comprehensively by the provisions of

section 75 of the Contracts Act 1950.

2.3.3

Statutory Provisions

In Malaysia, the consequences of breach of contract are amply covered under

Part VII of the Contracts Act 1950 principally in the following sections. 48

a)

Section 74 – Compensation For Loss Or Damage Caused By Breach Of

Contract.

(1) When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by the breach is

entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract,

compensation for any loss or damages caused to him thereby, which

naturally arose in the usual course of things from the breach, or which

the parties knew, when they made the contract, to be likely to result from

the breach of it. 49

47

[1966] 2 MLJ 155. See also Selva Kumar a/l Murugiah v Thiaragajah a/l Retnasamy [1955] 1 MLJ

817.

48

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.202

49

see Hadley v Baxendale [1854] 9 Ex 341

25

(2) Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or

damages sustained by reason of the breach. 50

(3) When an obligation resembling those created by contract has been

incurred and has not been discharged, any person injured by the failure

to discharge it is entitled to receive the same compensation from the

party in default as if the person had contracted to discharge it and had

broken his contract.

Explanation – In estimating the loss or damage arising from a breach of

contract, the means which existed of remedying the inconvenience caused by

the non-performance of the contract must be taken into account.

b)

Section 75 – Compensation For Breach Of Contract Where Penalty Is

Stipulated For.

When a contract has been broken, if a sum is named in the contract as the

amount to be paid in case of such breach, or if the contract contains any other

stipulation by way of penalty, the party complaining of the breach is entitled,

whether or not actual loss is proved to have been caused thereby, to receive

from the party who has broken the contract, reasonable compensation not

exceeding the amount so named or, as the case may be, the penalty stipulated

for. 51

Explanation – A stipulation for increased interest from the date of default

may be a stipulation by way of penalty….

50

51

see Tham Cheow Toh v Associated Metal Smelters Ltd [1972] 1 MLJ 171

see Wearne Brothers (M) Ltd v Jackson [1966] 2 MLJ 155

26

c)

Section 76 – Party Rightfully Rescinding Contract Entitled To

Compensation.

A person who rightfully rescinds a contract is entitled to compensation for

any damages which he has sustained through the non-fulfilment of the

contract.

2.3.4

Recovery of Damages

The limits to a plaintiff’s claim for damages under the English law are

governed by the rules relating to the remoteness of damage in contracts. 52 The

classic statement on this aspect of the law can be found in the judgement of Alderson

B in Hadley v Baxendale. 53 The rule enunciated by Alderson B was subsequently

explained in Victoria (Laundry Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd. 54

In Malaysia, section 74 of the Contracts Act sets out the consequences of a

breach of contract and the rule embodied in section 74 has its origin in the rule as

expounded in Hadley v Baxendale. 55

Section 74 of the Contracts Act limits a

plaintiff’s claim for damages caused by a breach of contract.

There are two limbs under section 74 (1) under which compensation become

to the injured party. 56

52

Dato’ Visu sinnadurai (1987). The Law of contract in Malaysia and Singapore: Cases and

Commentary. 2nd ed., pp.669

53

[1854] 9 Ex 341; 156 ER 145

54

[1949] 2 KB 528

55

Dato’ Visu sinnadurai (1987). The Law of contract in Malaysia and Singapore: Cases and

Commentary. 2nd ed., pp.670

56

Syed Ahmad Alsagoff. (2003). The Principles of the Law of Contract in Malaysia. 2nd ed., pp.370

27

1.

When the damage or loss caused to the injured party arose naturally in

the usual course of things fro the breach.

2.

When the parties to the contract were fully aware at the time when

they made the contract that damage or loss or likely to result from the

breach.

In either situation, the compensation claimable must not be too remote or

indirect. 57

2.3.4.1 Remoteness of Damage

A party culpable of breaching a contract is not generally liable for all

damages, which ensues from his breach of contract. 58 Some damage is said to be too

remote and therefore irrecoverable.

In contract, the general rule governing the

remoteness of damage was laid down in the case of Hadley v Baxendale 59 in the

following words:

When two parties have made a contract which one of them has broken, the

damages which the other party ought to receive in respect of such breach of

contract should be such as may fairly and reasonably be considered either

arising naturally, i.e according to the usual course of thing from such breach

of contract itself, or such as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the

contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the

probable result of the breach of it.

57

Ibid, pp.370

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.204

59

1854] 9 Ex 341; 156 ER 145

58

28

In summary, the rule in Hadley v Baxendale comprises of two limbs, i.e: in

the first limb, damages arising naturally or directly; in the second limb, damages as

may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties at the

time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it.

The Contracts Act 1950 had codified the common law rule in Hadley v

Baxendale in the form of section 74(1). This fact has been expressly acknowledged

by local courts in a string of cases, notable of; Tham Cheow Toh v Associated Metal

Smelters Ltd 60 , and Toeh Kee Keong v Tambun mining Co. Ltd. 61 In Tham Cheow

Toh v Associated Metal Smelters Ltd, the appellant had agreed to sell a metal furnace

to the respondent and giving a responsibility that the melting furnace would have a

temperature of not lower than 2,600 degree F. This specification was not fulfilled

and consequently, the respondent brought an action alleging breach of condition and

claimed damages, including loss of profits.

The Federal Court pointed out that the appellant would not liable for the

payment of damages for loss of profits unless there was evidence showing that the

special object of the furnace had been drawn to their attention and they are contracted

on the basis liable to the payment of loss of profits. On the facts, the appellant was

knew about the requirement of producing the specified temperature and the urgency

of delivery. Therefore, they were liable to pay for the certain loss of profits suffered

by the respondent.

Again, the rules were applied in a prominent Scottish’s case, Balfour Beatty

Construction (Scotland) Ltd v Scottish Power plc. 62 . In this case, the plaintiffs were

constructing a concrete aqueduct over a main road, installed a concrete batching

plant and arranged for electricity to be supplied by the defendants. The plaintiffs

needed to pour all the concrete in a single continuous operation and so, when the

60

[1972] 1 MLJ 171

[1968] 1 MLJ 39

62

[1994] 71 BLR 20

61

29

electricity supply failed during the pour, the plaintiffs had to demolish all the works,

which had been done. The case was held that although the defendant were clearly in

breach of contract, they were not liable for these consequences, since they had not

been told that a continuous pour was essential.

In short, the loss recoverable is subjected to the provision that such

compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained

as a result from the breach.

2.3.4.2 Measure of Damage

The measure of damages in contract is the principle involved in the

assessment of the actual monetary compensation that needs to be paid to the innocent

party for the damage sustained as a result of the breach of contract.63 Under the

common law, damages may be claimed under two established principles, namely:

1.

Principle in Robinson v Harman 64

The quantum of damage is assessed in the dictum that provided the

damages suffered is not too remote, the innocent party is entitled to be

placed, so far as money can do it, to the position he would have been,

had the contract been performed (or that the particular damage had not

occurred), ie there must be restitution in integrum. 65

63

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.206

64

[1848] 1 Ex 850

65

Harbans Singh. (2004). Engineering and Construction Contracts Management: Law and Principles.

Selangor: Malayan Law Journal Sdn. Bhd., pp.206

30

2.

Principle under the Rule in Hadley v Baxendale 66

The quantum of damage is assessed on the premise that provided the

damage suffered is not too remote, the innocent party is entitled to

receive damages which are fairly and reasonable considered to be

either arising naturally, i.e according to the usual course of things

from such breach of contract itself or such as may reasonably be

supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties at the time

they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it.

From the two principles adverted earlier, the second principle as codified in

section 74 of the Contracts Act 1950 is commonly employed locally.

2.3.5

Proof of Damages

A plaintiff claiming damages for breach of contract must produce evidence in

court of the loss that he has suffered because of the breach. 67 In the absence of

documentary evidence, the court can make a reasonable evaluation of the loss

incurred. However, the plaintiff must lead at least sufficient or satisfactory evidence

to enable the court to make a fair and reasonable assumption of loss. 68

A local case in relation to construction contracts, SEA Housing Corporation

Sdn. Bhd. v Lee Poh Choo 69 , the developer delayed in completing the house and the

owner claimed for her loss of use and enjoyment of the house at a monthly rate at

RM 2,500.

Her evidence was that she called the developer’s office and was

informed that the rental would be at that monthly rate, without witness or document

66

[1854] 9 Ex 341

Syed Ahmad Alsagoff. (2003). The Principles of the Law of Contract in Malaysia. 2nd ed., pp.387

68

Ibid

69

[1982] 1 MLJ 324

67

31

to sustain her claim. The Judge, Mohamed Dzaiddin held that the house owner could

not recover his loss as she failed to prove her loss of her house and occupation of the

said building by was of rental. Therefore, party who claim for damages they will

have the duty to prove their damages.

In recovery of special damages, plaintiff must have to plead and prove to his

claim. In another local case, Syed Jaafar bin Syed Ibrahim v Maju Mehar Singh