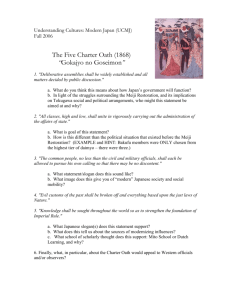

Chapter 17: The Japanese Transition to Democracy and Back A. Introduction

advertisement