Part II: Liberal Trends in Constitutional Reforms of the Nineteenth Century Historical Narratives:

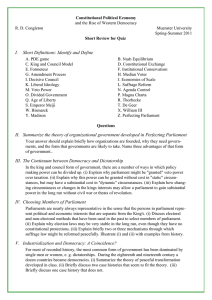

advertisement