Chapter 10: Constitutional Exchange in England: From the Glorious

advertisement

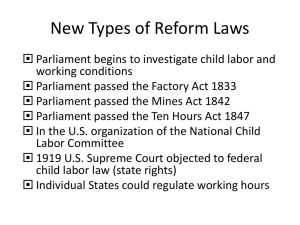

republican government (Claydon, 15). During his adult life, William had become very adept at building support both within the provincial governments and in the States General in order to reclaim the stadtholdership and to secure the monies he desired for national defense--national security being the primary charge of the Dutch stadtholders. (Claydon, 25). As King of England, William continued to have conflict with France and the security of the Netherlands very much on his mind, and he was very interested in raising English support and money for war with France. This is not to say that William was less interested in power and wealth than previous kings, nor that war with France was not in England's long term interests, but it is to say that William, as opposed to Charles II and James II, was very concerned about French power, and was used to working within constitutional constraints to advance his interests in a manner that they were not.103 It is also bears noting that William's crown was more dependent on parliamentary support than had previously been the case, insofar as James II continued to have the more legitimate hereditary claim to the throne. William, consequently, was more interested in parliamentary good will and more willing to trade royal prerogatives for tax revenues than most previous English kings. The parliament, in contrast, was more self-assured and independent than the one that restored the Stuart monarchy, and also more interested in shoring up its own authority. The announcemnt of French support for James II's effort to recapture the English and Scottish thrones, increased parliament's own interest in supporting William's campaign against France. James II might not be as generous as his brother had been after the civil war. Opportunities for constitutional exchange between king and parliament were, consequently, the strongest they had been since the Magna Carta was signed four and a Chapter 10: Constitutional Exchange in England: From the Glorious Revolution to Universal Suffrage 1. Constitutional Exchanges and the Glorious Revolution: William III and the Parliament Although the medieval English constitution remained in place, both the parties in power and their circumstances were substantially different than they had been in the past. This, more than the reaffirmation of the English bill of rights affected the course of public policy during the next several decades. William III was not the usual English heir to the throne. He was not a young Stuart raised in a royal and sovereign English household, but rather an experienced middle-aged man from the most distinguished family in the Netherlands. It is important to recall that in the Dutch republic, sovereignty rested with the states rather than with the House of Orange. The Netherlands was organized as a confederation of provincial governments, which themselves were often organized as confederations of local governments. The stadholdership was a regional office rather than a national one, and the provincial governments could create and eliminate stadtholderships, as Holland had recently done.101 The office of stadtholder was usually combined with the office of captain general, and rose in importance during wars and was diminished (and sometime eliminated) during times of peace. This, of course, is the opposite of the English Crown's historical relationship with parliament. Essentially unanimous support within the States General was necessary to obtain resources for the Dutch military.102 From an early age, William had been educated in the fields most useful for a future Stadholder: in military matters and in strategies for negotiating with a sovereign 101 The office of stadtholder was usually combined with the office of captain general, and rose in importance during wars and diminished during times of peace. For example, Holland, the most important of Province, had eliminated the office of Stadholdership in 1654, partly at the behest of Cromwell (Israel, 722-3). Holland's stadholdership remained defunct until the French invasion of 1672 (Israel, 802). 102 The confederal structure of the Netherlands indirectly gave the city of Amsterdam a veto over national tax requests. Amsterdam have the largest tax base of any community in both Holland and the Netherlands. The province of Holland generally used unanimous agreement to pass on major tax and military bills (Claydon, 24-5). The province of Holland had similar veto power in the national States General. 103 For example, in 1672, William refused King Charles II's (his uncle) offer to press for his elevation to the King of Holland as part of a peace settlement with France. He refused, in part because the offer involved a smaller Netherlands, and in part because "his countryman were more attached to their liberties than they would be to any royal ruler." (Claydon, 19) Shortly thereafter, in gratitude for its liberation from the French, the elites of the province of Gelderland offered William III the sovereign office of duke, rather than the appointed office of stadtholder, which would have ended that province's republican form of government. Several other provinces complained that a Gelderland Dukedom would undermine the Dutch Constitution. William, perhaps with greater aims in mind, refused the elevation to Duke and accepted the lesser post of Stadtholder (Claydon, 23). 100 parliament by keeping it in session for more than a decade as Charles II had done immediately after the restoration. The precedent of parliamentary audit and increased parliamentary control over expenditures were partly a consequence of William's effort to win the trust of parliament on military matters, and thus more resources for his French campaigns. Parliament's power of the purse, ceded early in his administration, when William relinquished several of the revenue sources used by kings and queen over the past century. Resistance, at this point, might have undermined his efforts to fund military campaigns (e.g. to pay the Dutch army) and to build a more powerful British military to confront France on the continent and abroad. The power of the purse allowed parliament substantial control of the military. This is perhaps most apparent, when following the peace of Ryswick in 1697, the British army was reduced to less than a third of William's request, approximately an eighth of its peak during the nine years war. In 1699, parliament induced William to disband his trusted Dutch guards (Claydon, 146-51). In 1698 the civil list act increased William's allotment of tax revenues for life with the caveat that the new tax revenues only up to £700,000 per year could be used for his royal expenses. Revenues beyond that could only be used with parliamentary permission. The latter prevented William (and his successors) from unilaterally increasing rates on the royal income sources in order to secure independence from the parliament as the Charles' and James' had done. Had government expenditures not increase so much, the income from royal properties together with the customs revenues for life might have been sufficient to fund peacetime governance, as £2,000,000 had been sufficient a decade or two before. In the present environment royal incomes were evidently far below that required for peacetime government finace, which made William and his successors, whether at peace or a war, more dependent on Parliamentary subsidies. Finally, in 1701, William accepted the Act of Settlement. This act was not binding on William, but was to bind his successors. The first part of the act affirms Princess Anne's position and greatly elevated the German Electors of Hanover in the line of secession. The second part of the act is of greater constitutional interest, because it half centuries earlier. A deferential, rule following, and resource hungry king with urgent duties abroad confronted a parliament anxious to expand its control over the crown. The constitutional bargains struck over the next dozen years were pivotal events in both English and Dutch history. William's success with the parliament is evident in the enormous funding that Parliament provided him for his war with France. The tax base was expanded and tax rates were increased. Tax receipts more than doubled over those of James II, rising from 2 million to over 5 million pounds in 1694 (Claydon, 125-6). Expenditures rose even more rapidly, with the consequence that British debt expanded to unprecedented levels (North and Weingast, 1989), accomplished in part via the Dutch method of ear-marking some taxes for debt service and repayment.104 Central government employment tripled in size from 4000 under James II to 12,000 under William, while the British army and navy approximately doubled in size during the nine years war (Claydon, 126). The long term geopolitical success of the William's long-standing "English strategy" is also obvious.105 The British had been inclined to intervene on the French side under Charles II and James II, but after William III, the English efforts to contain French influence continued for three centuries (Morgan, 402). The Netherlands survived as an independent country. On the other hand, the price paid for parliament's support in the nine year war with France (1688-1697) was also clear. The Coronation Act of 1689 required the sovereign to "solemnly promise and swear to govern the people of this Kingdom of England,..., according to the statutes in Parliament agreed on, and the laws and customs of the same." Parliaments advanced William the traditional customs duties for life, which as ever were too little to support large-scale military campaigns, but all other taxes were extended for short periods between one and four years. In 1694, a second Triennial Act was passed which (again) required parliaments to be called at least once every three years, but this time limited the terms of parliaments to three years. The Triennial Act together with the parliament's new short term tax policies required more frequent elections to the commons, which made the house of commons, more independent of the crown. No longer, could a King "lock in" an especially amiable 104 Interest paid on foreign debt fell significantly over the period of William's reign, evidently in large part because of the adoption of Dutch practices (Stasavage, 74-8) , which facilitated the large scale borrowing necessary to fund a good deal of the great military expansion. 105 His interest in bringing England over to the Dutch side in its contests with France dates at least back to 1677 when he arranged to marry Princess Mary, who was at that time second in the line of secession, after her father (Claydon, 23-4). 101 invitation, representatives could be routinely judged by their electorates, however small and elite they might have been, at least once every three years. The power of the purse had been increased by ceding control of many revenue sources to the parliament that had previously been used by kings at the same time that the size of and cost of governance expanded to well beyond the royal household's remaining revenues. The precedent of audit and earmarked budgets reduced the sovereign's discretion to use tax receipts as they might desire, and further reduced opportunities for a king to buy support in parliament. Freedom of speech and petition opened up the domain of public discussion on a variety of matters that previously might have been deemed treasonous and punished accordingly. attempts to constrain future sovereigns, especially those born outside of Great Britain. It requires future sovereigns to "join in communion with the Church of England." This new Anglican requirement was more restrictive than required under the 1689 Bill of Rights. Mary, who had died in 1694, would have been eligible for the crown under the new rules, but not William. William was himself Protestant, and, thus, satisfied the 1689 requirements, but he was brought up in the Dutch reform church, which was more Presbyterian than Anglican (Claydon, 99). The Act of Settlement also forbade future kings (from other lands) from engaging in war outside England without the permission of parliament, and prevented all future sovereigns from leaving "the domains of England, Scotland, or Ireland without the consent of Parliament." The act of settlement also elevated the privy council somewhat and specified that, "no persons born out of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, or Ireland, ... , shall be capable to be of the Privy Council, or a member of either House of Parliament." The latter ended the centuries old custom by which the King was automatically a member of the House of Lords, which reduced the Hannoverian kings' ability to directly monitor and negotiate with members of the Lords. The Settlement also reduced royal opportunities for influencing the parliament by declaring that "no person who has an office or place of profit under the King, or receives a pension from the crown, shall be capable of serving as a member of the House of Commons." (This last provision was, subsequently, weakened by the Regency Act of 1706, which required new elections for MPs who became crown employees. This was a much milder restriction, because elections at the time were rarely contested.) Finally, the settlement increased judicial independence by making senior judges life time appoints during good behavior, "judges commissions be made quam diu se bene gesseint," subject only to parliamentary impeachment. By the time of William's unexpected death in 1702, both the formal and informal constitutions of England had been rewritten to increase Parliamentary independence and control over governance.106 Parliaments could meet regularly--with or without royal 2. Royal Power after the Glorious Revolution It was not necessarily the case that these precedents and Acts of parliament would continue to bind future queens and kings. All English constitutional changes are entirely reversible, because the written constitution is not protected by a formal amendment process. A clever king who constructed an amiable parliament could, in principle, repeal or amend all these acts by simple majority votes. Precedent is to a significant extent in the eye of the beholder. Fiscal precedents could be ignored or reinterpreted by congenial parliaments or by kings, as they had been for hundreds of years. Just as many routine disputes under common law are based on disagreements about what the "the law" is, so were many of the long-standing disputes between parliaments and kings in previous centuries. Moreover, then as now, there is no formal procedure by which constitutional violations can be set aside. However, the center of policy making power did not shift back to the Crown as it had on previous occassions. Instead, parliament continued to strengthen its grip on governance during the following century.107 Formal and informal institutional reforms made the parliament increasingly independent, and the next several Kings and Queens were for various reasons were less adept at using patronage and royal innovation to influence parliament or to go round it.108 Political parties evolved into more disciplined 106 William, the heroic military leader of many campaigns, died from injuries sustained after falling off a horse. In this, it could be argued that William achieved his stated goal, announced on October 10 1688 just before the invasion in his Declaration of Reasons: "a free and lawful parliament ... and securing to the whole nation the free enjoyment of all their laws, rights and liberties under a just and legal government." The complete text of William's declaration is available at http://www.jacobite.ca/documents/16881010.htm. 108 William, himself, spent the summers of the Eight Year war on the continent leading military campaigns against the French. Queen Anne (1702-14), whose succession was a consequence of the 1689 Bill of Rights which elevated her above her father and brother, had lived in Denmark with her husband for many years before inheriting the crown, was not trained for leadership, and often suffered from 107 102 account for the whole of parliament, nor were the blocks organized in the modern sense. Being a member of parliament was not a full-time salaried position. Relatively few elections were contested, and MP's attended parliament, more or less at their convenience. The lack of party discipline and professionalism, along with the preponderance of uncontested elections, allowed patronage to affect the balance of power (Field, 140-1). For example the Whigs took power shortly after George I's accession to the crown, in part, because George only appointed Whigs to senior positions in government. The Whigs remained largely in control until George III's accession in 1760, who was less favorably disposed toward partisan politics, in general, and to Whigs in particular than his grand father and great grand father had been. Under George III, the Tories assumed power for the first time in 50 years.110 Neither the party system nor cabinet governance had yet emerged. On the other hand, although the crown could appoint and remove ministers, kings and queens now routinely needed parliament in a way that they had rarely needed parliaments before. The year-to-year tax policy adopted by parliament during William's reign, necessitated annual meetings of parliament, and implied that the King needed ministers who could pass annual tax legislation. This was new. Shifts in the composition of the House of Commons generated by party campaigns and external events, limited the Crown's choice of ministers and affected the ordinary course of public policy, because the King needed ministers who could deliver majorities in both chambers can could only influence rather than control the membership of parliament. The Crown's personal revenue sources were far more circumscribed than they had been, and the size of government was far larger than it had been in the centuries before William III's reign. A man like Walpole who deliver majorities in parliament (and the King's patronage for parliament) was clearly a powerful and influential statesman.111 organizations that made the parliament more difficult for kings to manipulate, while the bargaining power of the various persons holding the crown declined. As a consequence, the next century saw a gradual but steady and substantial shift of power from the crown to the parliament, although not the end of the crown's role in British politics. Although it is often written that the glorious revolution created parliamentary governance in England, Royal power did not disappear with the Bill of Rights, nor with the death of William. The last sovereign to veto a parliamentary decision after it was passed by majorities in both houses was William's successor, Queen Anne, who vetoed the Scottish militia bill in 1707. However, she was not the last to affect the course of public policy in the small, or in the large. The division of power between king and parliament had clearly shifted from king toward parliament between 1689 and 1702, but to an intermediate point rather than from one extreme to the other. The Crown continued to have and to exercise the power to appoint and dismiss ministers, to call and dismiss parliament, and to directly affect the composition of parliament by through town charters and elevation. The power of royal patronage, although reduced after the budgetary and audit practices implemented during William's reign, was still a potent method of influencing the behavior of members of parliament. Although there were many patrons, the Crown was by far the largest. Queen Anne had a hundred "placemen" in parliament (Field, 141). A third of the house of commons was on the executive payroll during George I and II.109 Indeed, the most important of the constitutional reforms of the 19th and 20th century, the election reform of 1832 and the Parliament Act of 1911, occurred in large part because of threatened interventions by the Crown. More or less stable political blocks of MPs had formed in both chambers towards the end of the 17th century (Hayton, 2002; Hill, Ch. 2), however these blocks did not ill-health. The first two Hanovian Kings, King George I and II (1714-1760) were, like William, foreign born. George I spoke German rather than English at court. And, finally, although George III had clear effects on the course of policy on many occasions, he was mentally ill for much of his long reign (1760-1820). 109 Walpole (1721-1742) is often regard to be the first Prime Minister, had the ear of both George I and George II, and used both parliamentary and royal patronage to his and the crown's mutual advantage. They essentially excluded Tories from government positions. On the other hand, it was the Whigs superior access to foreign credit as well as the latent Jacobism of many Tories, that initially predisposed George I to favor Whig ministers (Field, 146; Hill, 59, 77). 110 In his words, George III wanted to "put an end to those unhappy distinctions of party called Whigs and Tories by declaring that I would countenance every man that supported my Administration." Quoted in Hill, p. 105-6. He proceeded to appoint his nonpartisan tutor, the Earl of Brute to be his chief minister. The king, true to his word, subsequently appoint men who would put king over party, both Tories and Whigs, to posts in his administration (Hill, 106). 103 the commons, the Tory base of support being in the upper middle gentry (Field, 143; Hill, 51). The Septennial Act of 1716 allowed an existing Whig parliament to be extended without an intervening election and provided them (and George I) with four more years to use patronage to cement the Whig control of parliament. After the Septennial Act, the written rules of the political game remained stable for more than a century, but the unwritten procedures of governance continued to be revised to take account of the rising cost of governance and a century-long sequence of foreign kings.112 Many of these informal revisions were indirect consequences of the new budgetary circumstances of the Crown. As the size of governance increased well beyond the crown's own revenues, parliamentary "subsidies" became essential for governance (Mathias, 39). The short term tax bills passed by parliament, in turn, necessitated both annual meetings of parliament and royal ministers who could easily deliver majorities in both Lords and Commons. As a consequence, it became commonplace for the Crown's leading minister to be a leading member of the majority coalition in parliament. Once selected, such a leader would generally be allowed to dispense the crown's patronage (jobs) in a manner that would cement his authority in the parliament. This reliance on a single parliamentary leader to craft majority support through policies and royal patronage, as with Walpole and Pitt, helped established organizational patterns and norms that allowed the modern office of prime minister to emerge. The "prime minister's" team, his elite councils of compatriots and advisors, gradually became more involved in major policy decisions and in setting the legislative agenda in parliament, especially on policy matters that the crown had no obvious interest. As the scope of government increased and royal interests focused on foreign polices of the expanding empire, more and more of routine domestic policies were turned over to the council of ministers. The use of ministerial councils was, of course, an ancient royal management technique, but in the present case the need for ongoing parliamentary majorities A new intermediate form of government had emerged, with neither parliament nor crown fully dominant. Although the power of the crown gradually diminished through time, as formal and informal changes in the British constitution were adopted, the crown remained a significant determinant of parliamentary policy well into the 19th century. 3. The Power of the Purse, Constitutional Exchange, and the Emergence of Parliamentary Governance: 1702-1832 Several significant reforms of the written constitution were adopted during the first decades of the eighteenth century. Two of these demonstrate the easy reversability of the English constitutional law of this time. The 1701 Act of Settlement included a major impediment to using patronage to influence parliament by forbidding those on the royal payroll from sitting in the parliament. This separation of the executive and parliament was weakened substantially by the Regency Act of 1706, which required MPs obtaining royal jobs to stand for new elections--elections which were often uncontested. The Scottish Union Act of 1707 bought Scotland firmly into the England sphere by abolishing the Scottish parliament, linking the crowns of Scotland and England. Forty five new seats were created in Commons for Scottish town and county representatives and 9 new peers for the Lords. A revised property qualification for the Commons was adopted in 1711. County representatives (knights) had to have 600 pounds of income per year and Burgesses 300 pounds per year. The Septennial Act of 1716 revised the Trienial Act and extended the maximal length of parliament from 3 to 7 years, reducing what little electoral competition there was, and by most accounts increase corruption by further strengthening patronage. To some extent, these constitutional reforms can be interpreted as "ordinary" partisan majoritarian politics, insofar as the reforms were intended to advance Tory or Whig political objectives. For example, the Scottish Union was adopted by a Whig majority, and the new Scottish members subsequently voted with the Whigs. The Tories adopted a property qualification in 1711 to reduce part of the Whig support in 111 Robert Walpole is often regarded to be the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. He lead the majority in Commons from 1721-1742. The term "prime minister" was coined with him in mind; however, this title was not meant as a complement, but as an insult composed by Walpole's enemies (Field 145). Perhaps, Walpole appeared to be too deferential to George I and II? Walpole was not, of course, the first minister in English history to have had a great effect on English public policy, but he was the first to do so in the post William III era when ongoing parliamentary majorities played an important role in policy formation. 112 William III (1689-1702), George I (1714-27) and George II (1727-60) were foreign by birth. Anne (1702-1714) had lived in Denmark with her husband for nearly 20 years prior to her assention. George III (1760-1820) was born in Britain, but evidently spoke English with a German accent, possibly because he had a Germon speaking mother, father, and wife. 104 Whig dynasty fell (Field, 136-7. 146,149). This royal influence over the composition of parliament continues well into the nineteenth century. Although the role of "placemen" declined somewhat during Pitt's term as prime minister and ministerial power increased somewhat, King George III's implicit veto of catholic emancipation was sufficient to induce Pitt and his talented cabinet to resign in 1801. George IV (1820-30) was known to favor Tories, and, subsequently, had a Tory majority in parliament--partly because he expanded Lords from 339 to 400 members (Field, 164). William IV (1930-37) was known to favor Whigs, and the Tory majority was replaced by a Whig majority in the election that followed his accession to the crown (Pugh, 48; Lee, 58-9). Political speech had not yet become free outside the Parliament. Thomas Paine had to flee the country for France in 1792 after Pitt condemned his "monstrous doctrine" (Pugh, 1999). The long-standing Test Act of 1673 prevented dissenters and Catholics from seeking parliamentary office until 1829. The 1711 property qualifcations for Commons prevented non-wealthy Anglicans from sitting in commons until 1859. Population shifts had greatly reduced the representativeness of borough governments, to the extent that it had ever existed. The great new industrial centers of Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, and Sheffield, 4 of the 7 largest cities in England, had only county representation (2 MPs). There were 49 two member districts with fewer than 50 eligible voters (Field, 142). By 1800, Parliament had far more political power than it had ever had before--indeed dominant policy making power--but British governance was by no means democratic or representative in the modern sense. Royal and Aristocratic interests largely ruled the day, although that day was gradually coming to an end. substantially reduced the range of ministers who could be hired (or fired) by the Crown. The King or Queen remained the principal, but more and more authority was delegated to his or her ministers. The ministers, in turn, support, became increasingly independent of the sovereign, because of the requirement for continuing parliamentary majorities on taxations. In this way, the use of a parliamentary "prime minister" to manage majorities in the Commons and Lords gradually lead to cabinet governance. Cabinet governance in its modern sense, however, did not emerge until well into the nineteenth century. It should be remembered that British politics in the 18th century was not characterized by the competitive elections and intense electioneering that are the trademarks of modern democracies. Parties were loose coalitions of members with common interets rather than disciplined national organizations that crafted platforms and provided substantial electoral support. Many borough elections and most county elections were uncontested and were substantially controlled by local elites (O'Gorman, 334). In 1761 only four of forty county elections were contested, and only forty two of two hundred three borough elections (Field, 143). During the eighteenth century it became increasingly common for borough seats to be controled by local elites as the number of "nomination" boroughs increased from approximately 60 to more than 200 during the course of the century. Indeed, it became increasingly common to purchase nominations. The price of a seat in Commons was bid up from 1000 pounds to 5000 pounds over the course of the century. (O'Gorman, 1989, p. 13, 21). Local elites who sold "their seats" would deliver the necessary votes and/or prevent opposition. The Crown could not fully determine the composition of parliament anymore than it could in previous centuries, but the sovereign could and evidently did significantly influence its composition throughout the eighteenth century. Together, traditions of royal deference and the large number of nomination seats allowed the Crown to influenced the composition of Commons. Elevation and patronage allowed the Crown to influence the composition of the Lords. Consequently, both kings and queens were normally "blessed" with parliamentary majorities whose interests were compatible with their own interests. George I and George II preferred Whigs to Tories, in part because of tory support for James II and James III's claim to the throne--and Whigs majorities George I and II had. George III was less partisan and less pedisposed toward Whigs, and the 4. Ideological Interests and Interest Groups in the Late Eighteenth Century Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a series of economic, technological, political and ideological shocks began to transform the largely medieval lifestyles and political outlooks of the British commonor and elite. Both International and intranational trade expanded rapidly during the eighteenth century, reflecting agricultural innovation, declining transportation costs, and population growth (Mathias, 88, 66-7). English turnpike and canal systems expanded dramatically during the mid to late eighteenth century generated a more integrated domestic economic market (Morgan 428-9,483), while the expanding empire and 105 and women organized to improve their own wealth through collective bargaining, and also to achieve political ends (Pugh, 22; Mathias, 334). Interest in parliamentary reform was not a new phenomena. Parliamentary reform had been seriously debated in the public domain at least since the Leveler's "Aggreement" of 1647. However, the late eighteenth century revolutions in American and in France renewed interest in suffrage reform, and the growth of large scale textile firms in Northern England lead to the development of major new urban centers that were not accounted for under the current apportionment of seats in Commons. Consequently, a variety of groups took up the cause of parliamentary reform at the end of the century: Society for Constitutional Information (1791), the Friends of Univesal Peace and Rights of Man (1791), the London Correspondence Society (1792), Friends of the People (1792), and Sheffield Association (1792). These were, by in large, middle class groups, but membership in such organizations extended both into parliamentary elites and into the working class (Lee, 16; Hill, 150-1,Pugh, 22-3). These groups organized large scale, and more or less peaceful, demonstrations and petition drives that promoted reform rather than revolution. In 1797, Earl Grey, who was a member of Friends of the People and became Prime Minister in 1830, sponsored a parliamentary reform bill that received only 94 votes in commons (Hill, 233).113 Not all reform demonstrations were peaceful, and the reform movement induced the formation of anti-reform groups, which lead to more violent conflicts. Rumours of revolt and revolutionary plots were abundent during those days and France declared war in 1793. England shifted to a war footing and curtailed civil liberties to quell demonstrations. The Habeas Corpus Act was suspended in 1794. The Treasonable and Seditious Practices Act and the Sedititious Meeting Act were passed in 1793 by large supper majorities. Treasonable practices included the transport and publication of writing opposed to the constitution. Paines publisher was sentenced to a year and half in jail for selling the Rights of Man. Meetings of more than 50 persons were allowed only with magistrate approval. Thence forth, large demonstrations in opposition to the Seditious Meetings acts were themselves seditious and broken up. In 1799, prosperity in northern Europe increased international trade worldwide (Mathias, 87-8). New large scale techniques for spinning thread and weaving cloth lead to major new manufacturing centers (Mathias, 243-5), and the industrial revolution began to gather steam with the Watt's modifications of Newcombe's steam engine in the 1774 and 1781 (Morgan, 480). Population expanded, and thanks to with large scale manufacturing and expanded commerce new urban centers emerged and older commercial centers grew larger . Reduced transportation costs also allowed a boader and more rapid dissemination of news and opinion which lead to a more integrated political market. Newspapers became commonplace during the early 18th century, which greatly increased political literacy, or at least increased the breath of political scandals disseminated. A number of influential books were published in the late 18th century by thoughtful men interested in major economic and political reform. Adam Smith's (1776) thoughtful defense of free trade and specialization helped to energize economic liberals for the next two century. Jeremy Bentham's (1789) Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation challenged the customary foundation of law and suggests that both laws and institutions should promote the greatest happiness to the greatest number. His utilitarian arguments continue to affect modern policy debates. Burke's Reflections on the French Revolution was published in 1990 suggests that institutional design, particularly revolutionary design is unlikely to improve long-standing institutions, thereby establishing a rational foundation for institutional conservatism. Paine's rebuttal, the Rights of Man elevated the concept of individual rights in English constitutional debates. His book immediately sold 200,000 copies in 1793 (Field, 156). Petitions and mass demonstrations became increasingly common events. The new middle and upper middle class were largely excluded from political life by the wealth requirements for suffrage and membership in the Commons, many joined or supported groups that lobbied for expansion of suffrage. Industrialists organized groups such as the General Chamber of Manufactures and petitioned parliament for favorable policies and reforms of parliament (Morgan, 482) Groups of working men 113 Some three decades later, Grey became prime minister in more favorable circumstances, and finally passed a bill very similar to his first. Grey's 1797 bill, however, was not the first effort at reforming the rotten boroughs. Reform bills had been offerred even before the French Revolution. For example, in 1785, Pitt had attempted to move seats from the smaller boroughs to the larger ones in Reform bill that included compensation for the "owners" of the small borough seats. In this case, as in 1797, George III was opposed to reform and helped marshal opposition to the bill (Hill, 145). Indeed, Grey's 1797 effort was largely opposed by his own party as well, as Pitt's interest in reform had disappeared after the French Revolution (Hill, 50-1). 106 freer to organize. It also became easier to establish networks between existing clubs, and correspondence societies provided links between the clubs with broader interests, including public policy (Lee, 54; O'Gorman, 312). Well over a hundred politically active groups organized mass meetings, petition drives, and demonstrations, issued pamphlets, and lobbied ministers behinds the scenes (Hamer, 8; Lopatin, 1999, appendix). There were, of course, many objections to the current rules for selecting members of Commons, and proposal for reform varied widely. However, it was widely agreed that seats in Commons were disproportionately allocated to the south, that many of the existing seats were controlled by small local elites, and that many others were not only uncontested. There were some 270 seats from "nomination boroughs" out of the 658 members of Commons (Lee, 57-9; O'Gorman, 26). Moreover, the northern industrial centers were essentially unrepresented in Commons. The county of Lancastershire had a population of over 1.3 million and returned just two members, while Cornwall with a population of three hundred thousand returned 42 members. This did not mean that all elections to commons were simply empty rituals, but it did mean that few seats were selected by broad electorates.116 Niether of the mainstream parties favored a wholesale redistribution of seats nor universal suffrage, but many Whigs had favored a reallocation of seats and for revisions of borough suffrage rules for decades. correspondance societies and trade unions were banned under the Corresponding and Combination Acts (Lee, 19;Field, 157). These "gag acts" as well as medieval laws defining treason were used to prosecute and harras reform, peace and labor organizers, which essentially postponed large scale efforts to promote reform until well after the war with Napolean ended in 1814.114 Both industrialization and democratic revolutions abroad, in the United States and in France, focused attention on the economic and political interests of a rapidly growing and increasingly organized middle class. The language of politics often tends to be intense and emotional, and although there was no counterpart to the American or French revolutions in the United Kingdom, there were outspoken demonstrations, riots, and petition drives which did affect policy indirectly.115 The American and French revolutions also brought constitutional issues directly to the literate public. 5. The "Great Reform" English Governance: 1800 - 1835. Not all organizations were affected by these acts, or the subsequent restrictions passed in 1819 (the Six Acts). For example, "friendly societies" continued to flourish as did local reform oriented newspapers. In 1801, approximately 700,000 people belonged to such local service clubs. By 1815, membership approached a million and by 1830 approximatly, one in four males were members (Gerrard, 2002, p. 169). The Masons continued to expand their membership and influence. With the repeal of the 1799 combination act in 1824, local trade associations and unions became 114 See Field, 156-62; Pugh, 22-24; Hill, 155; Lee, 54; Morgan, 486-8; and Holmberg, 2002. After the war, reform groups sprung up again and organized large scale demonstrations and petition drives. For example, in 1816 more than 400 petitions favoring the abolition of the income tax arrived in parliament (Hill, 176). Although the anti-tax efforts were successful, the reform movements were not. Again parliament reponded to large scale demonstrations with legislation curtaling those groups, the Six Acts of 1819, rather than reform. Juriy trials lessoned the impact of these laws insofar as they did not routinely convict those charged or apply maximal sentences. The treason act of 1351 defined seven offences as high treason, including various assaults upon the royal family and "levying war against the king within his realm or adhering to his enemies." (Holmberg, 2002) 115 Not all of these demonstrations were peaceful, but no coordinated uprisings or attacks on government buildings or persons took place. Indeed it was often quite the reverse as in the Peterloo "massacre" in 1819 when eleven persons at a parliamentary reform meeting were killed by a cavalry charge during a very large but, evidently, peaceful meeting at St. Peters Field in Manchester. The speakers were arrested, as were the newspaper reporters who wrote up accounts of the meeting and cavalry charge. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peterloo_massacre ) 116 The borrough electorates at that time varied widely. At the least represtative boroughs had suffrage rights that were attached to particular peices of property, "burgages," which could be assembled under a single ownership; this allowed a single person to select an MP. Many others were selected by very small electorates, as with the "rotten" borough of Sarum. At the other extreme were boroughs in which all free holders or all taxpayers were entitled to vote (O'Gorman, 1989, p. 21-33). In these more liberal boroughs, the suffrage reforms of 1832 actually reduced suffrage! The composition of the electorate for Commons varied widely; however, on average, the electorate was surprisingly middle class, with skilled craftsmen being the largest group. Recall that the electorate for selecting county and borough representatives to Commons incuded approximately 10-12% of the adult male population. Garrard (2002, p. 26) reports that the electorate in 1830 was composed as follows: 13.6% were landed gentry, 5.8% were merchants and manufacturers, 20% were retailers, 39.5% were skilled craftmen, 19.2% were semiskilled workman, and 6.4% were employed in agricultural. 107 After the defeat in Lords, Grey's ministry resigned, and King William encouraged the formation of a minority Tory government. When this failed, he invited Grey to return to government and agreed to create 41 pro-reform peers, if necessary, to assure passage of the reform act (LeMay, 32). A third reform bill, modified slightly to please the Lords, again easily passed commons.117 The changes, the external pressure, and the royal threat induced a majority of the Lords to accept the reform. The King accepted the bill and the first substantial reform of election laws in 400 years took effect. The great reform approximately doubled the electorate to approximatly 20% of adult males by broadening the franchise in most boroughs to include all households rated at 10 pounds per year, and by increasing the county roles to include 50 pound renters as well as 40 shilling householder enfranchised under the medieval suffrage law of 1430. One hundred and forty three seats were taken from the smaller boroughs, includindg 112 from boroughs with populations under 1000. Sixty five seats went to the new industrial centers, sixty five more to county representatives, and the remainder were redistributed to London, Scotland, and Ireland. The great reform did not fully solve the disprotionate representation of the south relative to the north, radically expand suffrage or fully end patronage, but it did make patronage less decisive in future elections and political competition more so (Lee, 61).118 It also changed the representative basis of the house of commons from a more or less equal representation of boroughs and counties to a system more based on electorate size (Jennings, 13). The redistribution of seats change the distribution of economic interests represented in parliament, as the new industrial interests became better represented. The expansion of suffrage induced changes in the technology of securing majorities in Commons. Both these effects had substantial political and, thereby, constitutional effects in the long run. Parliamentary reform, of course, was politically easier for the Whigs to do for two reasons. First, the preponderance of the reallocated seats would come from Tory districts. Of the 270 nomination districts most likely to be affected by reform, only 70 routinely returned Whigs (Lee, 57). Second, the Whigs had long been a reform coalition by the standards of the early 19th century (Hill, 178). For example the Whig coalition had long opposed restrictions on freedom of the press, pressed for free trade, including repeal of the corn law act of 1815, opposed laws forbidding catholics and dissenters from holding public office, and had proposed several parliamentary reform bills. Public pressure eventually persuaded a majority of the prereform electorate that reform was inevitable, and even, perhaps, influenced a future king. (George IV's brother William IV had served in the Lords, and generally supported the Whigs during his time there.) George IV died in 1830 and the election associated with William IV's accession returned a pro-reform Whig government later in the year, thanks in part to William IV's support (Phillips, 1992, p. 18-21). A flood of 1200 petitions was presented to parliament mostly favoring reform (O'Gorman, 310). The new Whig government proposed a reform bill that called for a major reallocation of seats, uniform rules for the election of burough MPs, and a substantial expansion of suffrage. The Whig proposal was defeated narrowly in the Common at the second reading. Earl Grey asked William IV to call for new elections, and parliament was dismissed. The ensuing campaign focused largely on reform, and returned a large Whig majority to Commons. Grey's coalition received 71.1% of the votes cast in Great Britain (Rallings and Thrasher, 2000, p.3). In thirty five of the forty county elections, the Whigs took both seats. Of the 187 Tories elected, 90 percent came from districts that would lose their seats if the Whig reforms were adopted (Hill, 1996, p.193). This time the reform easily passed Commons, but a majority of the Lords disagreed, and the reform was vetoed, 199 to 158. The rejection of reform by the Lords lead to scattered riots, some of which were targeted at peers and bishops who had opposed reform. It also induced a middle class tax revolt and bank boycott. The middle class widely witheld taxes and withdraw funds from the banks. As a consequence, the Bank of England's reserves fell by 40% (Hill, 195). 6. The Gradual Expansion of Suffrage During the Nineteenth Century: The Second and Third Reforms The creation of a more competitive environment for elections to Commons made majorities in commons more difficult to engineer than they had under the previous regime. Although nomination boroughs still existed after 1832, there were far 117 The modifications implied that fewer seats would be shifted from England to Scotland (6) and Ireland (5). Suffrage in local elections was more extended in 1835 by the Municipal Corporation Act. It replaced 178 unelected corporate municipalities in Wales and England with elected town councils, and extended the vote to all property owners, subject to 30 month residency. 118 108 subject to royal manipulation and ministers more dependent on their support, both of which further reduced the influence of the Crown over public policy in the United Kingdom. However, that these reforms would inevitably lead to further constitutional reforms was not clear. The Chartist movement of the 1840s pressed for universal male sufferage as well as the secret ballot, free trade, and the reform of the poor laws. The Chartist's failed to obtain significant constitutional reform, in part because some prominent members of the movement threatened law and order, which induced a conservative back lash against constitutional reform. Interest in suffrage reform, however, did not end with the Chartist movement, as reform activists continued to press for reform. Reform bills were introduced by "advanced liberals" in 1852 and 1854 and defeated by overwelming, but diminishing majorities (Smith, 29). Electoral support for reform among was evidenty sufficient to induce the conservatives to take up the reform issue, and in 1859 the conservatives introduced a reform bill (Smith, 41), partly with the aim of protecting conservative interests in the face of "inevitable" reform.119 New regional reform organizations, with roots in the Chartist and anti-Corn Law leagues, added to the pressure in the 1860s (Smith, 29, 39-40). The Reform Union was formed in the northern industrial centers by "radical" politicians, merchants, and prominent reformer in 1864 to press for liberal reforms including the secret ballot, a return to triennial parliaments, redistributing seats in Commons in proportion to borough and county populations, and a very broad franchise to include all males not on poor relief. They emphasized the universality of the interests advanced by their programs, citing Mill and Gladstone rather than class-based arguments (Cowling, 243-2). The Reform League was founded in London during 1864, by middle class and working class activists. Its funding came from lessor lords and industrialists, and from the Trade Council. It promoted a similar constitutional agenda, but used somewhat more agressive and radical language to promote reform (Cowling, 246, 248). In 1865, the London Working Men's Association was formed largely from members of the trade unions to campaign for a broad franchise including lodgers not on poor relief (Cowling, 247). These three groups organized numerous talks in medium sized towns fewer of them than before. More opinions, consequently, had to be influenced after the reform than before in order to obtain a seat in the house of commons, which induced a change in electoral technology. In economic terms, the reforms reduced the effectiveness of targetted patronage relative to organized campaigns to disseminate information. Economics implies that poltically active individual and groups would therefore refine their electoral strategies accordingly. In the short run, the effectiveness of existing local and national interest groups increased relative to the Crown and local potentates, who could still dispense favors and jobs but no longer as decisively. In the long run, the change in the relative effectiveness of patronage relative to informational campaigns (and substantial local public progects) would induce local potentates and the Crown to support existing politically active groups that advanced their interests, to promote the formation of new groups and alliances that might also advance their policy and political aims, and to dispense local "pork barrel" projects favored by local electorates in addition to patronage to local political leaders. Granting more seats to the industrial districts made the center of gravity in Commons more interested in industrial development than before. Trade policies were liberalized, monopolies reduced, and the free trade zone of the empire expanded to make up for losses in North America. Innovations in manufacturing gave British manufactures a cost advantage in several markets which generated large trade surpluses and capital inflows. Although those elected to office were often from the landed elite (Pugh, 82), they were, none the less, responsive to local economic and political interests (Schonhardt- Bailey, xxxx). Economic policies changed, and per capita income grew four times as fast in the 1830-50 period as it had in the previous century (Pugh, 36). The two reforms of 1832, thus, indirectly encouraged the development of modern economic and political organizations in nineteenth century Britain: large firms and political parties, and political and economic unions such as the Chartest and Anti-Corn Law Leagues. It can, thus, be said that constitutional reforms lead to prosperity, mass politics, and petition drives. The increasing importance of the increasingly disciplined political parties and interest groups also made elections less 119 In May of 1859, Disraeli argued in Commons that parliamentary reform had become a pressing matter of public policy. "Thus Parliamentary Reform becames a public question, a public question in due cousre of time becomes a Parliamentary question; and then, as it were, shedding its last skin becomes a Ministerial question. Reform has been for 15 years a Parliamentary question and for 10 years it has been a Ministerial question" (Quoted in LeMay, 180). Disraeli's remarks clearly imply that interest groups may directly establish an issue as a "public question" and indirectly establish an issue as a ministerial issue. 109 Three suffrage issues were quickly linked in the Derby-Disraeli government: suffrage extension for national elections, a modest redistribution of seats in commons, and suffrage extention in the boroughs for local elections. The Disraeli reform proposals were more radical than those rejected in the previous year, but were subtly crafted at the margins to benefit conservative electoral interests in light of careful demographic research. The boundaries of boroughs were expanded to remove liberals from county electorates, which remained subject to a higher property restriction, while the borough franchise was expanded beyond the level sought by the Liberals to include renters who might be influenced by their Tory landlords. After a good deal of debate and ammendment, the bill was passed by a coalition of pro-reform liberals and conservatives over the opposition of mainstream liberals who objected to the conservative biases of the new bill.122 The new electorate was nearly doubled, increasing from just over a million in 1866 to just under two million in 1668 in England, and from 1.35 million to 2.48 million in the United Kingdom as a whole. However, the expansion was disproportionately focused on the boroughs where electorates rose from 600 thousand to 1.43 million while that in the counties rose from 758 thousand to just over a million (Smith, 236). Although the borough seats became more representative in the modern sense, they did not have proportionately more representatives in Commons. Only thirty seats from the smallest districts were redistributed, and only about half went to boroughs. The rural south remained over-represented relative to the industrial midlands. The nineteen largest boroughs with a combined population of 5 million returned 46 MPs, while the sixty eight smallest boroughs with an aggregate population of four hundred twenty thousand returned 68 MPs (Smith, 240). and cities throughout England, and partly because their members included journalists as well as elected politicians, their views were widely reported in the press throughout the country. Constitutional reform was again on the mainstream political agenda. In the 1865 elections, there was a changing of the guard as a new generation of members entered Commons for the first time and as the baton of leadership was passed on to new leaders. Earl Russell with the assistance of Gladstone formed a Liberal reform government, with the support of Liberals, Whigs, and radicals (advanced liberals). Early in 1866, Russell proposed a major reform expanding the national suffrage laws substantially beyond that of 1832, although short of that advocated by the reform groups.120 The Russell-Gladstone reform bill obtained a slim majority in Commons on its first reading--one that was much smaller than anticipated because of large scale defections among whig MPs--but the bill failed in second reading (after ammendment) in the face of conservative and Whig opposition. Parliament was recessed, and during the recess, the Reform League and Working Men's Association organized large scale demonstrations in favor or expanding the sufferage throughout the country, including several large and occasionally disorderly demonstrations within London itself (Cowling, 11-12; Smith, 135, 160).121 The Russell cabinet resigned without requesting new elections, and the Queen asked the leader of the opposition, Derby, to form a new government. A new conservative cabinet was formed in 1867 with the able assistance of Disraeli. It relied on the support of conservatives, conservative whigs (the Cave faction) and some radicals in the Commons. As in 1832, there was again royal support for suffrage reform. In her speech to parliament and in subsequent letters to the Derby, the Queen insisted that electoral reform should be addressed by the new government (Smith, 135). 120 Gladstone, for example argued in Commons on May 1864 for a limited expansion of suffrage, to include those "fit" to participate in national politics: "every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness of of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the constitution. [That is to say,] fitness for the franchise, when it shown to exist--as I say that it is shown to exist in the case of a select portion of the working class--is not repelled on sufficient grounds from the portals of the Constitution by the allegation that things are well as they are (quoted in LeMay, 184)" 121 One of the demonstrations is often referred to as the Hyde Park Riot. The riot began as a peaceful march, but involved an unlawful tresspass in Hyde park and some distruction of park property. The police tried to disburse the 20,000 person crowd, at which point a riot ensued. The police were rebuffed with sticks and stones. Several dozen demonstrators and policement were injured in the fray. One policeman subsequently died from injuries. The Calvalry was called out, and the crowd peacefully disbursed. The demonstrators were not entirely political, nor were they surly revolutionists, as games were played throughout the park and trees were climbed. All this took place within sight of Disraeli's apartment, which may have contributed to their influence. The queen evidently took the demonstrations seriously. Mrs. Disreali reported that "the people in general seem to be thoroughly enjoying themselves" (Smith, 129-131, 135). 122 One of the many proposed amendments was sponsored by J. S. Mill who attempted to replace the work "man" with the word "person," which would have expanded suffrage to women. Mill's woman's suffrage proposal received only 73 votes in support (Smith, 204). 110 in England. In the fourteenth century, meetings of a bicameral parliament to consider tax proposal and suggest laws to the crown had become routine. The upper chamber of the parliament included the nobility and senior church officials and the lower chamber included leaders from towns and counties. Although occassionally referred to as the Commons, the lower chamber was explicitly reserved for knights and squires for most of its history, and was consequently peopled with successful businessmen and farmers, and the children of nobles who were not in line for the family title and seat in the Lords. Although parliamentary power ebbed and flowed with the king's need for new tax revenues, the power of the medieval English parliament remained modest by modern standards. For most of the next two hundred centuries, parliaments met irregularly and for relatively short periods of time. Only the veto power the Parliament over new taxes continued essentially uninterrupted. Other protections and powers were obtained by various parliaments and then lost or ignored according to the interests and ambitions of the king or queen of the day. Parliaments were called and dismissed by the crown, and consequently, were often called only when the crown needed additional revenues (subsidies). Other councils whose members were hand picked by the crown played an ongoing role in governance, rather than parliament. A permanent shift of power from the King to the Parliament did not occur until the end of the Seventeenth century, during the reign of William III. This is nearly a century earlier than for the other countries in this study, and reflects unusual opportunities for constitutional exchange between William and the parliament at the time of William and Mary's accession. The English eighteenth century, like the Swedish one, demonstrates that it is possibile to have parliamentary governance without highly contested elections or broad suffrage. The democratization of British politics took place during essentialy at the same time as in the other northern kingdoms, largely in the period between 1825 and 1925--a period in which large scale liberal and labor movements arose that favored suffrage expansion. The conservative advantage was evident in the next elections. For example, in 1874 the conservatives received 38.32 percent of the votes cast in England and Wales, which elected 154 MPs. The Liberals recieved only slight fewer votes, 37.39 percent, but returned only 101 MPs (Smith, 225). In effect, the "advanced liberals" from the industrial midland and northern boroughs got increased suffrage but not increased representation, while the country gentry were protected from a substantial increase in electoral competition. About 1 in 8 persons living in boroughs were eligible to vote after the reforms but only about 1 in 15 persons residing in counties.123 The expansion of suffrage induced a further expansion of partisan organizations and, consequently of party discipline, which hastened the evolution of British politics and parliamentary voting patterns to their modern forms. In 1860, only about 58.9 percent of liberals voted with their government and 63.0 percent of conservatives routinely opposed it. By 1881, 83.2 percent of the liberals supported their party leaders on critical votes and 87.9 percent of conservatives. Party line voting reached the ninety percent levels in both parties in the following decade (LeMay, 178). 7. The Modern Parliamentary Democracy Emerges 1906-1928 In 1906 the liberals swept the parliamentary elections to an extent not seen since 1832. 400 liberals were elected, which along with the support of 40 members of labor and 83 Irish nationalists gave them a large supermajority of the 670 members of parliament. Yet the Lords, with a large conservative heriditary majority, ignored public sentiment, and continued to oppose liberal legislation, includingin 1909 the budget for national government. Another constitutional crisis was at hand, as Lords had violated the norm that clear messages from the electorate be taken seriously (LeMay, 189-192). In response, the House leadership embarked on another series of major constitutional reforms, the first of which adopted in 1911 changed for the five century old equality of Commons and Lords over legislation, and replaced it with a new constitution that formalized the dominance of Commons. 8. Improving Governance through Constitutional Reform: Summary The medieval English parliament emerged in the fourteenth and fifteenth century from earlier councils that emerged about about the same time that national government 123 The expansion of suffrage in Scotland and Irish counties were passed in separate bills in 1868 and were more substantial, although the final fraction of voters was smaller than in England and Wales, 1 in 24 and 1 in 26 respectively (Smith, 239). 111