Income Support and Social Services for

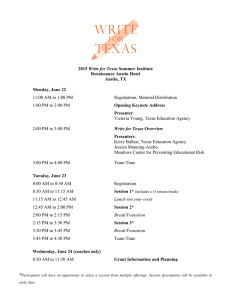

advertisement