I. Federalism as a Form of Polycentric Governance

advertisement

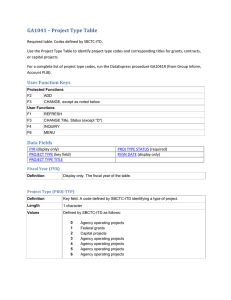

EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments I. Federalism as a Form of Polycentric Governance a. For example, in some cases a subset of local officials are appointed by higher levels of government. b. In other cases, local governments have relatively little ability to make tax, expenditure, or regulatory decisions. A. Thus far in the course, we have analyzed: i. the positive properties of a single tax or expenditure program in isolation ii. the normative properties of such taxes and expenditures iii. the normative or "economic" case for government services and regulation: externalities and public goods problems iv. and, the politics the underlie the main (large and well known) tax and expenditure programs selected by elected governments. v. All these analyses were grounded in relatively simple and general models of rational decision making. iii. The parliaments of most federal governments include a chamber that represents state (provincial, lander, etc.) interests. y Some political scientists insist that a truly federal government always have a chamber in the national legislature that represents state interests. y However, such a structure is not necessary for what economists refer to as “fiscal federalism.” y What is required for fiscal federalism is simply some local independence and some authority to make fiscal (tax and/or spending) decisions. B. We now turn to settings in which governments are not monolithic unitary organizations, but rather decentralized, federal, or confederal governments. i. Such policy making structures are common: within most countries, there are regional and local governments, as well as central (national or federal) governments. II. Public Finance in Federal Systems A. In cases in which several of the “levels” of government have independent taxing and/or spending authority, a country or nation state can be said to exhibit fiscal federalism (Oates 1972, 1977, 1999; see also Mueller in Congleton and Swedenborg 2006). For example, within the US, there are national (federal), state, county, and town governments. Similar divisions exist in most countries. ii. In most cases, the rules of the central government constrain the authority of the regional and local governments. iii. Nonetheless, in cases in which the various governments are independently elected--rather than appointed by the central government in some way--and the local governments have significant control over local fiscal and regulatory policy, the result is a decentralized, “polycentric” system of governance. i. Fiscal federalism does not require political federalism, but it does require “polycentric” governance (Ostrom 1972, McGinnis 1999, Hooghe and Marks 2003). C. In federal systems of governance, the central government is formally sovereign, rather than the “member” states, but the states have independent formal legal (constitutional) status. i. Federal states, thus, include a hierarchy of governments with more or less overlapping jurisdictions, but more or less independent policy making procedures. ii. Some federal systems are more decentralized than others, because their local governments are less independent and/or have less authority than in others. ii. The greater is the independence of local governments and the broader is their fiscal and regulatory authority, the more decentralized is a federal (or other polycentric) government. iii. In other less decentralized federal systems, control over many local taxes and expenditures is exercised by higher levels of governments. a. Within the US, individual state, county and town governments (local voters) can usually control local taxes and expenditures. b. Similar decentralized control over taxes and expenditures also exist in Canada, Australia and Switzerland. a. Independent state and local governments exist, but they are not able to set many (or any) local tax rates or may have very limited control over local expenditures. b. Fiscal federalism exists in such countries as well, if local governments can make some independent fiscal decisions. 1 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments iv. Within "unified" governments, local governments may also be more or less independent and more or less free to determine taxes, expenditures, borrowing, and regulations. C. Among the vertical relationships given most attention by economists are intergovernmental grants and political feedbacks. i. One important strand of state and local public finance explores the effects of "intergovernmental grants" on state and local policy choices. y Such states may be considered to be "federal" in the fiscal sense because taxing and/or spending authority is distributed between national, state, and local governments.) y Illustration of the effect of an intergovernmental grant on local expenditures. ii. Another concerns the political effects that "states" have on higher levels of government, insofar as state voters and their representatives have "regional" rather than national interests (See Knight in Congleton and Swedenborg 2006). Figure 1: Levels of Government Central Government a. The existence of intergovernmental grants and targeted grants tend to induce local and state governments to lobby in favor of such programs. b. One possible result is "Pork barrel politics" a.k.a. the "fiscal commons problem" (discussed below). Intergovernmental Grants Regional (State) Gov. 1 Local Gov A Local Gov B Local Gov C Regional (State) Gov. 2 Local Gov D iii. Still another concerns how bargaining between levels of government affect the extent of centralization observed (Congleton, Bacaarria, and Kyriacou 2003). iv. In addition to the vertical relationships, there are several “horizontal” relationships that are of interest to economists. Local Gov E a. For example, to the extent that "tax base" is mobile across local governmental jurisdictions, intergovernmental competition over taxes, expenditures, and regulation tends to emerge. If community A has higher taxes than Community C, people from community A will tend to move to community C--unless the services in community B are noticeably better than those in community C. (The effects of competition between government are discussed below.) b. There are also regulatory externalities that tend to be associated with local governments. B. Federal systems of governance have both “vertical” and “horizontal” relationships among governments. i. With respect to “vertical” relationships: some services and taxes may simply be mandated by higher levels of government. a. Local governments are constrained in what they can do by state laws. b. State governments are constrained in what the can do by national laws. c. In the diagram above, the red arrows can be thought of as "mandates" placed on local governments and/or as grants (subsidies) paid to local governments. D. The economics and politics of these fiscal relationships not only allow us to understand federal governments operate but also help us analyze how federal systems should be designed. ii. In addition to mandates and prohibitions from higher levels of government, there are often subsidies from "upper" levels of governments to "lower" levels of governments that create new opportunities for local governments to provide services without having to raise local taxes. III. The Effects of Intergovernmental Grants A. Modeling the effects of intergovernmental grants requires a model of local governmental decision making (Bradford and Oates 1971, Romer and Rosenthal 1980, Gramlich 1998). 2 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments b. (Add indifference curves to diagrams like that above, and analyze how different i. Within democracies, these can be based on the median voter model, perhaps augmented by the effects of interest groups and intergovernmental competition (see below). ii. The median voter model ( and median legislator model and governor models) allow the decisions of government to be modeled as if they were made by a single person. iii. This, in turn, allows us to use diagrams from microeconomics to represent the effects of conditional and unconditional grants on local governments. kinds of grants tend to affect the level and distribution of government services within a community.) iv. For the most part, the empirical evidence on the effects of grants is consistent with such one person (median voter) models of government decision making. v. There is however one puzzle, often termed the "fly paper effect" (Hamilton 1983, Bailey and Connolly 1998, Jacoby 2002). a. Block grants, which resemble lump sum grants, increase government services by more than one would expect based on standard consumer models. b. The grants "stick" to the programs they are aimed at, rather than inducing tax reductions that the median voter model seems to predict. That is to say, in a community that spends 10% of its income on government B. The median voter and intergovernmental grants. i. As was the case for ordinary subsidies, intergovernmental grants can be "lump sum" or "marginal" (block grants or matching grants). services why aren't 90% of block grants used to reduce taxes? y As true of ordinary subsidies, grants may also be conditional or not. (There are several theories that can be used to explain this, but all require more complex models of governance than our simple median voter model, and not all are very convincing.) ii. Both conditional and unconditional matching grants affect relative prices of alternative government services. y Both conditional and unconditional block grants have income effects but not relative price effects. IV. The Fiscal Commons Problem (aka the Pork Barrel Dilemma) A. The existence of intergovernmental grants creates incentives for state and local governments (and state representatives and senators) to lobby for programs that benefit their own states--even if they do not benefit the nation as a whole. i. The federal government funds specific highway and water projects that benefit only a particular city or metropolitan area, but which are paid for by taxes imposed on everyone in the country. The Median Voter's Allocation Problem G2 Lump Sum Grant T/Pg2 (Draw in the Median Voter's indifference curves to see the effects of these grants.) Conditional Lump Sum Grant No Grant Circumstance a. Programs that often have regional rather than national benefits include: flood insurance, hurricane relief, ports and harbor spending, railroad and airport subsidies. b. Many highway and irrigation projects, national parks, and museums also mainly produce local benefits. Matching Grant T/Pg1 G1 Gov Service 1 ii. Groups will press for targeted projects that generate benefits for them that are lower than their own tax costs. iii. How intergovernmental grants change the public budget constraint is illustrated above. How such grants affect public policy require adding the indifference curves of the "pivotal policy maker." a. Such targeted programs (ear marks) can lead to inefficient policies at the national level, because central government expenditures are normally funded with general revenues. a. For most of our purpose the relevant indifference curves are those of the median voter (or directly elected city planner). 3 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments b. In such cases, the national funding of local projects induces a good deal more lobbying than would occur if the projects were funded at local levels, because local benefits are more likely to exceed local tax costs if other taxpayers are paying most of the cost. the Pork Barrel Dilemma Region B iii. Most central government revenues are raised through broad-based taxes, as with the income tax, corporate income tax, and sales (VAT) tax. Build Road Don't Build Road A, B A, B Build W (-2, -3) ( +2, -4) Don't build W ( -4, +1) ( 0, 0) Region A y This implies that the cost of targeted programs are spread over the nation or state as a whole, even if benefits are only locally distributed. iv. Adopting such targeted programs requires majority support within the central government's legislature. a. The payoffs to the region B and region A coalitions consist of their own narrow benefits from their projects less half of the total cost of the projects adopted. a. Thus, not every possible project that has local support can be funded. b. However, it is possible that a majority of voters (or legislators) receives net benefits that are smaller than the costs imposed on the minority opposed to the project or program of interest. c. It is also possible for majority coalitions to be assembled for a group of earmarks that have benefits that are smaller than their costs for the nation as a whole. d. This problem is sometimes called the "fiscal commons" problem or the "pork barrel dilemma." y If neither project is built, no benefits and no costs are realized. y If just the road is built, then region A gets (1 - 10/5) = -4 in net benefits. Region B, on the other hand pays its share of the costs and receives only very small benefits (6 - 10/2) = +1. y If just the water project is built, then region A gets most of the benefits but pays only half the costs, (8 - 12/2) = +2. Region B gets its small benefit at the cost of half of the water project, (2 - 12/2) = -4. B. Illustration of the Pork Barrel Dilemma i. Consider two programs with negative social net benefits, but majority support from two narrow coalitions. y If both projects are built, Region A gets (1-4) = -3 and region B gets (2 - 4) = -2 in net benefits. b. Each coalition has incentives to press for passage of their project, regardless of what the other coalition does. Notice that the payoffs in this case resemble those of a Prisoner's dilemma game. Each group has a dominant strategy c. As a consequence, each project is adopted at the Nash equilibrium of this game. a. Each project has total costs that exceed its total benefits, but that regional benefits are greater than regional costs under central government financing, because of the use of general taxes. b. For the purposes of illustration, assume: y that a regional highway costs 10 billion dollars and provides 1 billion dollars of benefits to region A and 6 billion dollars of benefits to region B. y Assume also that a regional water project costs 12 billion dollars and generates 8 billion dollars of benefits for region A, but only 2 billion dollars of benefits for region B. y However, both coalitions would be better off if neither of the projects were actually built! iii. The fiscal commons problem arises because of fiscal externalities. One region's centrally funded programs impose costs on other regions, who have to pay for those projects even though they receive little if any benefit. ii. The following game matrix can be used to illustrate this pork barrel dilemma. 4 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments d. A tax-revenue maximizing government (leviathan) will set the tax rate to maximize revenue (at the top of the Laffer curve). iv. This problem can be avoided by (i) making the regions fund their own projects, (ii) by rigorously using cost benefit analysis, or (iii) by adopting a generality rule (see Buchanan and Congleton 1998). y Given R = tQ* = (at-bt2)(c)/(b+c), the revenue maximizing tax can be found by differentiating R with respect to t and setting the result equal to zero: a. (Explain why these three solutions would all solve the dilemma.) b. (Are there other solutions that would also avoid the PD outcome while allowing projects with positive net benefits to be built? For example, how might user fees or benefit taxes be applied?) y t* = a/2b which implies that Q* = (1/2)(ca/(b+c)) y Market output under leviathan taxation is exactly half the untaxed market quantity, see part a. e. Now suppose that taxes are imposed by two independent tax-revenue maximizing governments, in which case t = t1 +t2 and tax revenue for a single government is tiQ* ( where Q* can be written as in part b). C. Overlapping Tax Bases: Another Fiscal Commons Problem i. In cases in which government fiscal authority is decentralized, there can be competition between levels of governments, and in some cases governments at the same level, over a tax base. a. The problem of over using a given tax base is a fiscal externality problem is similar to the fiscal commons problem for expenditures outlined above, but in this case generates over taxation rather than over supply of services b. (Of course, both phenomena may occur with the same federal government.) c. The common tax base problem is one possible rational choice explanation for taxation beyond the level that maximizes revenue in a Laffer Curve diagram (Flowers, 1988). y For government 1 this is simply y R = t1Q* = t1 (a-bt)(c)/(b+c) = (a t1 - bt12 - bt1t2)(c)/(b+c) y Differentiating with respect to t1 , setting the result equal to zero, and solving for t1*, produces the best reply function for government 1: y t1* = (a-bt2)/2b y A similar function can be derived for the second government: ii. Consider the case in which excise taxes are imposed by two tax revenue maximizing governments on the same tax base (product or service market). y t2* = (a-bt1)/2b f. At the Nash equilibrium, both governments will be on their best reply functions. a. Suppose that the demand curve for this market is: QD = a - bP and the supply curve is QS = cP, with QD(P*) = QS(P*) in the pretax equilibrium. y Solving for the symmetric case, allows the Nash equilibrium taxes to be characterized: ti** = a/3b y In the absence of an excise tax, the market clearing price would have equated supply and demand: cp = a - bP , which implies that y This implies a combined tax of t= a/3b +a/3 = 2a/3b at the Nash equilibrium. y P* = a/(b+c) and Q* = cP* = ca/(b+c) b. In the case in which an excise tax of amount t is imposed, the condition for market clearing price(s) is QD(Pc*) = QS(Pc*-t) or c(Pc-t) = a - bPc. c. A bit of algebra allows the consumer and supplier price, market output, and tax revenue to be determined: y Note that this is higher than the revenue maximizing tax found in part c, (2/3)(a/b) > (1/2)(a/b). y Two leviathan governments that rely on the same tax base would jointly impose tax rates that are beyond the revenue maximum of a Laffer curve. g. Students should work this duopoly taxation problem out as an exercise. What happens if the number of governments is N rather than 2? Is this a more plausible scenario for democratic or autocratic governments? Explain. y Pc* = (a+ct)/(b+c) ; Ps* = (a+ct)/(b+c) - t = (a-bt)/(a+b); y Q* = (a-bt)(c)/(b+c) ; R = tQ* = (at-bt2 )(c)/(b+c) y Note that prices are higher for consumers, lower for firms, and overall market output is lower than in the untaxed setting. y (Students should work this linear taxation problem out as an exercise.) 5 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments V. Intergovernmental Competition: the Tiebout Model B. Tiebout's model provides one of the strongest arguments in support of decentralized governance. A. Charles Tiebout (1954) pointed out that intergovernmental competition between local governments can be very similar to competition between firms in competitive markets. y Decentralizing the provision of local services potentially allows voters to get just what they want from goverment--no more and no less. y That is to say, intergovernmental competition can generate patterns of local public services and taxes that are Pareto efficient. C. Although Tiebout may be a reasonable first approximation for competition between local governments (and condo associations) within a metropolitan area, clearly there are limits to its applicability--just as there are limits to the applicability of his theory of perfect competition in ordinary markets. i. How sensitive are the Tiebout results to the assumptions? i. Tiebout uses migration and changes in local tax bases to characterize a perfectly competitive version of intergovernmental competition at state and local levels. a. He assumes that moving from one community to another is costless and motivated entirely by differences in local public services and taxes. b. He also assumes that competition for residents produces a wide range of fiscal packages to choose from. c. In this model, "tax and service competition" can be very similar to "price and quality competition" in private competitive markets. a. Clearly, the cost of moving between governments is not trivial, and tends to vary with the level of government. Does this imply that none of the predictions will hold up? b. Or is there enough mobility into and out of communities within many regions to put competitive pressure on local governments? A large number of persons are always moving for other reasons and may choose communities in large part for the combination of services and taxes offered. ii. In the limit, "voting with one's feet" produces a competitive equilibrium among communities in which: a. Each community provides its bundle of public services at least cost. b. Every community is ideally sized to produce its bundle of services. c. Each community's residents are "homogeneous" in their demand for local public services. d. Each voter-resident pays the marginal cost of his own services. ii. Economies of scale or networks may reduce the number of competing "town-firms" that can be sustained in a "Tiebout world" in a manner that reduces the range of choice available to voter-taxpayer-consumers. The menu of government services that voter-taxpayer-consumers can choose from may be more limited than the Tiebout model implies. The effect of economies of scale parallel those in the microeconomic analysis of perfect competition vs. monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly. In such cases, local politics will again be an important determinant of citizen welfare. iii. Such tax and service combinations meet the Lindalh conditions for efficient provision of public services (as well as the Samuelsonian ones). iv. Note that this process does not require an effective political system to achieve Pareto efficient results, only very mobile tax payers who can take their part of the tax base with them. iii. The existence of intergovernmental externalities may also imply that some services are under provided locally and others are over provided. In order to tax mobile resources, communities (towns, states, and countries) have to provide services commensurate with their tax costs. Otherwise "public consumers" will vote with their feet and move to other places that provide better value for their tax dollars (taking "their tax bases" with them). a. The logic closely parallels our earlier analysis of externalities between individuals and/or firms. NIMBY problems may also emerge. Transfer programs may be underprovided. b. Solving externality and public goods problems may require "treaties-Coasian contracts" or "interventions by other levels of government." v. Intergovernmental competition does not always work as well as Tiebout suggests, but this idea has informed a good deal of discussion about the desirability of decentralizing the provision of services. 6 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments D. The existence of economies of scale and externalities provide an economic rationale for federal systems with several "levels" of government with responsibilities for providing services in different sized jurisdictions. $/G Losses from Cenralized Mandates of Uniform Provision of Local Public Services If Tiebout worked perfectly, it would imply that an efficient federal government would be composed largely of local governments with a very small central government with the sole task of guaranteeing citizen mobility among communities. (Explain why) Reduced NSB = a' + b' +c' MBal VI. The Economic Logic of Assigning Fiscal Responsibilities to Different Levels of Government MBbob A. The Tiebout case for decentralization suggests that services should be provide by government's with the smallest jurisdictions (territories) sufficient to realize all economies of scale for the service of interest. c' a' c' MC b' MBcathy a. Oates (1972) develops this point more formally with his decentralization theorem. b. The EU adopts this idea with its "subsidiarity principle." G*c G*b Qcentral G*a Q of governmetnt Service (G ) B. The optimal size of governmental that provide particular services can be analyzed by studying economies of scale in producing the services of interest.. i. Services with global economies of scale should be provided by the national government (national defense, macroeconomic policy, redistribution) ii. Services with that require relatively large service areas or numbers of customers should be produced by state governments. (regional highways, higher education, etc.) iii. And services that can be effectively provided in relatively small service areas or for relatively small customer bases should be provided by local governments. (police and fire protection, elementary education, local roads, sanitation services etc.) C. Wallace Oates (1972) argues that if policy or service X has an effect on region Z, then the whole region should be managed by one government. i. Similarly, it can be argued that the "service district" (regional governed) should be large enough to realize all economies of scale in producing the service of interest. a. For example, some forms of education, police services, and environmental regulation have only local effects. b. The Oates-Tiebout analysis suggests that responsibilities for those services should be local rather than state or national. c. (Variety is good in the Oates-Tiebout framework.) d. (Would fiscal equalization make sense in this framework? Discuss.) (Note that the simple production-based arguments imply that particular services should be provided by only a single level of government.) iv. Addressing problems of intergovernmental externalities and economies of scale will require governments with larger jurisdictions than those that provide local fire protection. ii. On the other hand, other services tend to have regional effects as with commuter networks, other forms of air and water pollution, and some forms of police authority. 7 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments iii. Large--but not national--externality problems, such as lake or river water pollution can be best addressed by state government or regional consortiums of states. iv. There are evidently great economies of scale in military force, which suggest that national governments should have responsibility for this service. ii. The same logic applies to international settings, insofar as governments may negotiate a treaty where the countries "trade regulations." a. For example, in the various international environmental treaties, countries agree to strengthen various environmental regulations to deal with an international externality. b. Examples include international water commissions (US and Canada, Sweden and Denmark) and international environmental treaties. y Similarly, insofar as the advantages of free trade zones increase with size, so the national government should have responsibility for maintaining free trade within the nation. C. Another solution possible within a country is to "ask" higher levels of government to regulate the matter of concern. a. Adjacent counties may ask states to regulate "county externalities," states may ask the federal government to regulate "inter state externalities." In Europe the regulation of many international externalities is coordinated by the European Community. b. Note that this solution is of limited value for international regulation and public good problems because there are no world or continental governments. The results of Coasian contracts can be highly imperfect (relative to Pareto VII. Externalities between Governments: A. There are cases in which a l government cannot adopt Pareto efficient regulations or service levels--even if it wants to--because part of the problem is generated by persons or companies outside their jurisdiction. i. In such cases, regulation itself can be an externality generating activity. a. For example, a town’s regulations on water pollution may impose externalities on towns further down stream. b. Similarly, the environmental and trade regulations in one nation state may impose benefits or costs on resident of other adjacent countries. optimality) in international settings. Discuss some of these. [We will analyze the demand for treaties and their effectiveness later in the course.] ii. Consequently, there may be unrealized gains to trade between governments regarding appropriate regulation. VIII. Political and Economic considerations when assigning or revising responsibilities among governments. B. There are two general methods for dealing with such governmental externality problems. i. First, the affected parties may attempt to negotiate a "Coasian" contract that "internalizes" the externality. A. These production and externality-based economic arguments, however, neglect the advantages of variation in the services provided and also the political costs associated with larger regional governments with greater monopoly power. i. There are political costs associated with merging quite different areas into a single metropolitan area. a. In a median voter model, the existence of externalities would provide the median voters of the communities of interest with an economic reason to coordinate their policy choices. b. That is to say, it is possible that Coasian contracts (regional alliances or treaties) may be used to address inter-jurisdictional externality problems. a. The community becomes more heterogeneous. b. Monitoring costs tend to increase. c. Each voter has a smaller effect on service levels through his locational choice and voting behavior. d. Competition tends to fall as the number of government service packages diminishes. y State and local governments may negotiate with each other and sign agreements to coordinate policies or to create a "special use district" of the same "size" as the externality. y (Examples include airport and transit authorities, as with those between NY, NJ and CN, or between VA, MD, and DC. y (Indeed, come "community mergers" may be just cartelizing behavior by local politicians who attempt to escape from competitive pressures.) 8 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments ii. It also bears noting that carefully assigning fiscal responsibilities to specific levels of government is only one method of addressing these kinds of problems. governments and, moreover, implies that political power within their respective democratic central governments is also likely to vary widely by state, lander, and province. a. Other solutions also exist, as noted in our previous analysis of solutions to externality problems. b. One can also use mandates and Pigovian subsidies and taxes (conditional grants) to address intergovernmental externality and public goods problems. c. The federal structure can also be left a bit open ended so that communities and states can form "consortiums" or "regional authorities" to address regional interests. (Treaties or Coasian Contracts). B. That regional interests and bargaining power vary is important for fiscal federalism, because national constitutions do not fully specify the degree of decentralization within a nation at any single point in time or through time. i. Rather, the degree of decentralization is determined by a series of political bargains within and between national and regional legislatures in which both the details of policy and the powers to make policies are negotiated and renegotiated through time. ii. Differences in the bargaining power and interests among participating governments is likely to affect the distribution of fiscal and regulatory authority adopted. B. The best (utilitarian or contractarian) assignment of authority for providing services to specific levels of government (should) take account of both economic and political costs. C. It bears noting, however, that in practice the degree of decentralization that occurs within a polity is determined by constitutional and quasi-constitutional negotiations rather than by utilitarian philosophers or economists. C. In Practice, a good deal of asymmetry is observed within federal and confederal systems. i. For example, in Spain, Navarra and the Basque communities have formal tax and expenditure powers beyond those of the other "autonomous communities." IX. Endogenous Decentralization and Asymmetric Federalism A. Most economic models of federalism assume that each government at a given level has the same authority to make fiscal and regulatory decisions. However, the assumption of uniform jurisdictional size and power is not completely accurate. i. For example, we observe significant differences in physical size, population, income, and political representation for state and local governments. Galicia and Catalonia have special authority over education, language, and culture. In Canada, Quebec has special powers to encourage the use of the French language and protect the French-Canadian culture. In the United Kingdom, the Scottish Parliament has significantly more policy-making authority than the Welsh Parliament. In the United States, Indian reservations have their own specific taxing and regulatory authority that differ from those of ordinary state governments. California, the most populous state, has unique powers of environmental regulation. In China, Hong Kong has been granted unique legal and political institutions: "one country, two systems." a. In the United States, California is physically the third largest state with 11% of the citizens, whereas Wyoming, the sixth largest state includes less than 1% of the U. S. population. b. Requejo (1996) notes that New South Wales includes 35% of the population of Australia, whereas Tasmania includes less than 3%. North Rhine Westfalia includes some 21% of the population of Germany, whereas Bremen includes less than 1% of the population. c. Uttar Pradesh includes 16% of the population of India, whereas Sikkim includes less than a twentieth of one percent. ii. Large cities in many countries often have powers of taxation and regulation that smaller cities lack or rarely use. New York City and Washington D. C. have their own income and sales taxes. ii. That population and population densities vary so widely implies that demands for local services also tend to vary widely among these regional iii. Asymmetries are also common among the members of large international organizations. 9 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments a. This provides the city with a unique source of revenue and also a unique economic advantage. b. Both effects allow the more autonomous government to provide a more attractive fiscal and economic environment for its residents than possible for otherwise similar governments. In the European Union, some members retain more autonomy than others inasmuch as they have opted out of or delayed membership in the menu of treaties that define the responsibilities of affiliated countries. The responsibilities of members of the United Nations with respect to military armaments, human rights, and environmental regulations are similarly defined through a series of treaties with quite different signatories. Different nations formally retain different degrees of autonomy both within and without these very decentralized confederations. ii. Light rail has the effect of reducing transport costs to city apartments, shops, and factories that operate in an otherwise competitive market. a. Individuals prefer to work for firms that are close to the rail lines, and consumers prefer to live and shop at stores near the rail lines—other things being equal—because the net of transport real wages are higher and net of transport prices are lower along the rail lines. b. This increases net benefits and profits for consumers and firms located near the rail lines. c. Moreover, rental revenue from the right of ways allows the favored city to reduce other tax rates within the city. D. Service differences across communities may also emerge in both decentralized and unified states, because communities may have unequal influence over the decisions of the central government because of differences in population, political heterogeneity, history, or size. i. For example, equal representation by population often implies unequal representation by regions or economic interests, and vice versa. In the US, some states have far more influence in the House than in the Senate, and these differences have been shown to influence the pattern of intergovernmental grants iii. Given these economic advantages, persons and firms from within the favored city and throughout the country of interest will attempt to relocate near to the rail lines of the favored city. ii. Unequal influence within the central government implies that central government policies will often favor some regions or communities over others. In principle, the favored city continues expanding its rail network and attracting tax base up to the point where the marginal increase in revenue and tax base generated by an extra kilometer of new right of way equals the marginal cost of the right of way less any loss in tax base generated by investor fears concerning the use of eminent domain—or until no private firm is willing to expand its rail network because traffic densities are too low to recover its costs. The latter, of course, expands outward from the city center as immigration of capital and labor occurs. Analysis of variation voting power has a long and distinguished history in the public choice literature. (See for example: Mueller, 1989.) However, this form of asymmetry is not the same as that analyzed here in which regional governments acquire different degrees of local policy-making authority. E. Asymmetric federalism exists whenever governments at the same level of geographic responsibility—towns, counties, cities, or states—have different regulatory and fiscal powers. iv. Although there is a limit to the urban growth encouraged by this city’s unique power of eminent domain, the favored city becomes an important commercial and cultural center well before this limit is reached. Its internal market and population expands. Such differences in policy authorities create a "supply-side" source of variation in government services, regulations, and taxes in addition to the standard demand-side variation in local demand stressed in models of local fiscal competition. Specialization increases; and wages and profits increase as productivity rise. Other cities that have to rely entirely upon private provision of rail services falter, because holdout problems make assembling long right of ways very difficult—indeed intractable—for private firms acting alone. The more autonomous city grows and prospers—while other similar cities that would have copied the strategy of the favored city are legally unable to do so. F. For example, consider the case in which only a single city is granted authority to use eminent domain to produce “right of ways” for light rail transport services. i. Suppose that the favored city sells or rents the right of ways to private railroad companies. 10 EC950 Handout 7: Fiscal Relationships Among Governments v. Other local fiscal and regulatory "privileges" can have similar effects, insofar as the additional authority allows favored governments to provide a more attractive fiscal package than legally possible for other similar governments. Internal Institutional Asymmetry within Federal Governments G. Asymmetric federalism may take a variety of institutional forms. i. Specific asymmetries may be created by a nation’s constitution by assigning different areas of competency to various regions of the country. ii. Alternatively, the constitution may allow the possibility of alternative internal arrangements that allow the formation of many levels and combinations of fiscal authority. Central Government Inter Regional Organization a. For example, a national constitution may simply allow states to organize themselves into various subnational organizations of states, cities, or counties. b. An international treaty organization may allow a subset of member states to pursue their own interests within the terms of the treaty. Regional Government 1 iii. This possibility allows a range of federal structures that is more complex than normally analyzed by economists. However, it is clear that that many internal organizational structures tend to produce asymmetric forms of fiscal federalism. Regional Government 2 Regional Government 3 H. Surprisingly little research has been done asymmetric forms of federalism. i. Tiebout, 1956, and Oates, 1972, pioneered the economic analysis of fiscal federalism and intergovernmental relationships. a. The figure below illustrates one such internal structure. b. If we interpret the interregional government as another level of centralized control, it is clear that local government 1 retains more autonomy than local governments 2 and 3, because it is not bound by the decisions of the regional government, if the regional government is not granted exclusive areas of competency. a. Inman and Rubinfeld (1997) provide a nice survey of issues in subsequent literature. b. Molander (2004) provide a more international review of fiscal federalism in unitary states. c. Qian and Weingast (1997) elaborate the role that federalism can play in solving various commitment and information problems. ii. None of these papers or books includes any reference or comments on asymmetric forms of federalism. a. Requejo (1996) analyses some general features of existing asymmetries within modern states. b. Congleton, Bacarria, and Kyriacou (2003) analyze the political foundations of asymmetric distribution of authority within nation states and international organizations. 11