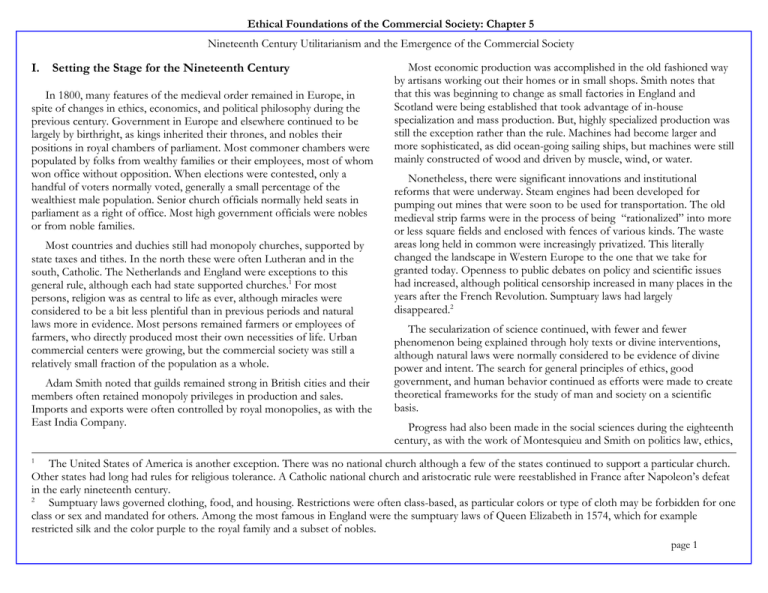

Nineteenth Century Utilitarianism and the Emergence of the Commercial Society

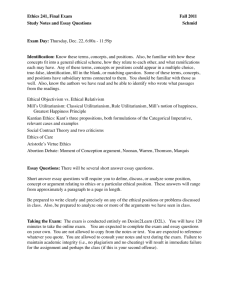

advertisement