Aristotle on Ethics and Markets

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

Aristotle on Ethics and Markets

I. Introduction: Why Philosophers, Political Scientists, and

Economists Still Study Aristotle

We being our discussion of ethics and the commercial society with

Aristotle’s work on ethics, politics, and economics. Although Part I focuses for the most part on philosophers and economists written after 1600,

Arisitotle’s work written nearly two thousand years earlier is often necessary to understand their arguments. Essentially all were familiar with his writings and in many cases their work was either an attempt to extend his ideas or to challenge them.

Aristotle wrote during the peak of the golden age of Athens in about

340 BCE. He was a former student of Plato, teacher of Alexander the

Great, and arguably the founder of several fields of philosophy, science, and social science. His ability to see lines of arguments--if not always to express them perfectly--allowed him to presage a surprisingly number of arguments in philosophy, economics, and political science. Aristotle work continues to be studied more than two thousand years after it was written, in part because it has influenced so many of the famous scholars that succeeded him, including religious scholars and secular philosophers through to the present.

His theories of ethics, economics, and politics were well known to the founders of contemporary economics and political science. Aristotle’s discussions included ideas that would later provide the foundations of contractarianism and utilitarianism. Critiques of his analysis would later produce Kantian ideas about universal law and duty, although there too his work provides ideas that would become central features of Kantian philosophy. His theories of relative prices, money, and inflation are still used today, although without attribution. It is clear, for example, that

Adam Smith was very familiar with Aristotle’s thought. Indeed, parts of

Smith’s philosophy and economics can be regarded as efforts to provide deeper foundations for Aristotle’s theories and to generalize them.

Aristotle’s secular philosophy also influenced various religious doctrines on personal conduct in 1600. Many of his ideas about ethics were incorporated into Western religious traditions. Wikipedia, for example, notes that: “In metaphysics, Aristotelians profoundly influenced

Judeo-Islamic philosophical and theological thought during the Middle

Ages and continues to influence Christian theology, especially the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. Aristotle was well known among medieval Muslim intellectuals and revered as ‘The First Teacher’.”

It is thus not entirely accidental that so many religious ideas about ethics are consistent with those developed by Aristotle, although he wrote several centuries before the Christian and Moslem religions were founded.

Aristotle’s major works were familiar to educated persons from the renaissance well into the twentieth century, because it was on the required reading lists of high schools and colleges throughout the West. during most of that period. That Aristotle continues to be read by scholars and college students implies that his ideas about ethics, politics, and markets have directly influenced millions of persons over the centuries. His influence on other scholars implies that he has indirectly affected millions of others who may not have read his major works. His indirect impact is further magnified through his influence on teachers, politicians, priests, and parents.

Aristotle’s work on ethics is thus a very useful point of departure for part I of the book. (1) He provides a coherent self-interest based theory of ethics, which delves into a variety of issues that are still of interest today.

(2) He also explicitly links ethics to markets, specifically ideas about justice, and suggests that work, production, and trade have roles in both a good life and good society.

His approach to knowledge begins with his own observations about the world, the arguments of others, and the rules of logic. Generalizable page 1

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 categories and relationships are discovered by eliminating (or at least reducing) inconsistencies and contradictions, and by looking for categories and relationships that encompass as much as possible about the subjects being analyzed. Problems and contradictions in the work of others and their lack of generality were often a stimulus to Aristotle’s own contributions. His goal, however, was not simply a better expression of other person’s ideas, but a more general and coherent theory.

1 this chapter. This provides a useful introduction to the subject matter of ethics, to the relationships between ethics and economics, and also summarizes some of his conclusions about political systems. The chapter uses more and somewhat longer excerpts from Aristotle’s work than subsequent chapters do in order to provide readers, many of whom will be unfamiliar with his work, with a sense of Aristotle’s fine grained and sophisticated (if not always linear) analysis.

2

His work on Logic, Physics, Biology, Ethics, Politics, and Economics all apply his analytical approach to knowledge. He employed it amazingly well and on an amazing range of topics, which is why so much of his work is still of interest nearly 2500 years after it was first written.

His work is not perfect, and his prose is often less linear than might be desired by comporary readers, at least as translated, but it is admired for its breadth and depth, for its many original insights, and for its profound influence on others.

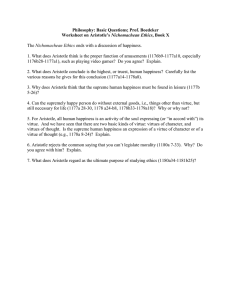

II. Nicomachean Ethics

Aristotle’s approach to ethics is partly empirical and partly deductive.

He believes that the purpose of ethics is to produce what would later be called the “good life,” which he regards to be a life of achievement, happiness and contentment. He takes a close look at persons who appear to be happy and content and attempts to determine aspects of their conduct that contribute to that happiness. He also considers what others in his society believe about virtue and virtue’s connection to happiness.

Aristotle’s methodology differs from that of the modern sciences in that he rarely, if ever, conducted experiments or statistical tests of his theories. (Statistics was developed much later.) Nonetheless, his deductive and synthetic approach continues to be one of the main ones used by contemporary researchers in the social sciences, in history, and philosophy.

It is also the main methodology of this book.

His aim is to identify underlying principles about how virtue contributes to happiness (eudaimonia), that are consistent with the moral intuitions of his time. From these principles, he develops a general outline of the types of conduct and decisionmaking that tend to produce happiness

(or contentment) in the long run. Long run happiness is the ultimate purpose of both moral choice and virtue in Aristotle’s analysis.

For the purposes of this book, insights from his two “practical” books are most relevant: Nicomachean Ethics and the Politics . It is these that provide his thoughts on the good life, the good society, and the appropriate role of commerce in private life and society.

Aristotle builds an empirical case in support of his theory, arguing that persons that invest in virtue tend to be happier, more content with their lives.

We begin with a review of some of his main arguments from the

Nicomachean Ethics , which will be referred to as the Ethics for remainder of

1 Among his many insights and arguments, Aristotle suggests that a young person “ is not a fit student of Moral Philosophy, for he has no experience in the actions of life ” ( Nicomachean Ethics (p. 26).]. There is some truth in this as in the rest of his arguments and conclusions, however, we’ll ignore his wisdom on this point for the purposes of this book. It is aimed as much at students as practicioners in the fields of economics and philosophy.

2 The kindle versions of the J. A. Smith (1937/2012) translation of the Nicomachean Ethics (A Public Domain Book) and the T. A. Sinclair (2009) translation of the

Politics (Penguin/Cybraria LLC) are used throughout this chapter. The punctuation and verb tenses of the excepts used have been slightly modernized to facilitate reading.

All bolding has been added by the author for emphasis. page 2

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

Aristotle’s analysis shows how one can create something general and systematic out of the haphazard collection of ethical theories that exists in a society at a given moment in time. It’s long term influence demonstrates that many of the conclusions of a theory of ethics can be general and robust, in that they continue to be used in other societies and in other times. He also argues, in passing, that ethics and economics are not entirely separate subjects, as many present-day scholars might argue..

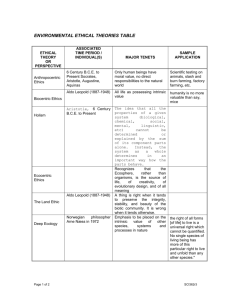

Figure 2.1 Schemata of Aristotle’s Theory of Moral Choice and Happiness

Human

Nature

Rational

Irrational

Circumstances

Moral

Choices

Other

Choices

Virtue

Producing

Vice

Producing

Other

Character

Happiness

III. Human Happiness as the Grounding for Ethics

The first step in Aristotle’s chain of analysis is the determination of whether there is anything general that can be said of human choices and actions. Is there a single essential purpose, an ultimate aim of human action, or not? If there is an ultimate purpose, are there common means that advance that purpose effectively? He answers yes to both questions. His arguments provide the basis for many contemporary normative theories and, perhaps surprisingly, for contemporary microeconomics.

A. The Pursuit of Happiness as the Ultimate End of Human

Action

Aristotle observes that happiness or contentment is widely pursued, and argues that insofar as it is pursued for its own sake, it is an “ultimate end.”

[W]hat good is that which we say [mankind] aims at? or, in other words, what is the highest of all the goods which are the objects of action?

So far as name goes, there is a pretty general agreement: for happiness both the multitude and the refined few call it, and “living well” and “doing well” they conceive to be the same with “being happy;” but about the nature of this happiness, men dispute. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 27).]

Aristotle next discusses several alternatives to happiness as ultimate ends, but argues that these too are normally methods for increasing one’s happiness.

Money and wealth are means rather than ultimate ends. They are pursued for other purposes. As for the life of money making, it is one of constraint, and wealth manifestly is not the good we are seeking, because it is for use, that is, for the sake of something further .

( Nichomachean Ethics (p. 29).)

[S]ince the ends are plainly many, and of these we choose some with a view to others (wealth, for instance, musical instruments, and, in general, all instruments), it is clear that all are not final. But, the chief good is manifestly something final . [ Nichomachean Ethics (p. 33).]

And of this nature Happiness is mostly thought to be, for this we choose always for its own sake, and never with a view to anything further. Whereas honor, pleasure, intellect, in fact every excellence we choose for their own sakes, it is true (because we would choose each of these even if no result were to follow), but we choose them also with a view to happiness. [ Nichomachean Ethics (pp. 33-34).] page 3

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

B. Work as a Method of Producing Excellence and Happiness

Given that happiness is the ultimate end of human action, what in general can be said about the most effective means of achieving it?

Aristotle argues that “work” is required to achieve happiness, in particular work that perfects one’s character.

[T]his object [happiness] may be easily attained, when we have discovered what is the work of man. As in the case of a flute-player, statuary, or artisan of any kind, or, more generally, all who have any work or course of action, their chief good and excellence is thought to reside in their work.

( Nicomachean Ethics (p. 34).)

What then can this be?

not mere life , because that plainly is shared with him even by vegetables, and we want what is peculiar to him. We must separate off then the life of mere nourishment and growth, and next will come the life of sensation: but this again manifestly is common to horses, oxen, and every animal.

[T]he Good of Man comes to be a working of the soul in the way of excellence , or, if Excellence admits of degrees, in the way of the best and most perfect excellence. And we must add, in a complete life; for as it is not one swallow or one fine day that makes a spring, so it is not one day or a short time that makes a man blessed and happy.

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 35).]

Human nature is not, according to Aristotle, simply given, an inflexible feature of nature, as often assumed in economic models and sociobiology, but something that individuals can choose to improve. They can invest time and energy in developing excellence and virtue or in mediocrity and vice.

However, work that perfecting one’s character is not by itself sufficient to assure happiness. Other material conditions are also necessary as well.

[I]t is quite plain that it [happiness] does require the addition of external goods , as we have said: because without appliances it is impossible, or at all events not easy, to do noble actions: for friends, money, and political influence are in a manner instruments whereby many things are done . [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 39).]

Happiness is a kind of contemplative speculation; but since it is man we are speaking of, he will need likewise external prosperity , because his nature is not by itself sufficient for speculation, but there must be health of body, and nourishment, and care of all kinds.

[ Nicomachean Ethics

(p. 277).]

Some of these external goods are inherited or available in a given social and natural environment, but many others are consequences of personal choices and thus also the result of intent or will.

C. General Types of Excellence that Lead to Human Happiness.

Aristotle observes that work is often associated with happiness, but that not all types of work produce it. Is there anything general that can be said about the kinds of work that produce happiness for human beings?

Aristotle suggests that there are two broad categories of work (or focuses of work) that do so. They are activities that improve a person’s character or soul: his or her intellectual and moral excellence. These,

Aristotle argues, are uniquely human capacities. A person’s intellectual excellence are not natural, but products of society and personal choice.

[H]uman Excellence is of two kinds, Intellectual and Moral: now the intellectual springs originally, and is increased subsequently, from teaching (for the most part that is), and needs therefore experience and time; whereas the moral comes from custom, and so the Greek term denoting it is but a slight deflection from the term denoting custom in that language. page 4

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

[

From this fact it is plain that custom . A stone, for instance, by nature gravitates downwards, could never by custom be brought to ascend.

Nicomachean Ethics

IV. Voluntary Choice as a Prerequisite for Improving One’s

Character

(p. 49).] not one of the moral virtues comes to be in us merely by nature: because of such things as exist by nature, none can be changed by

Given that one should work to perfect both one’s own intellectual and moral character, are there any general methods for doing so? Aristotle suggests that the correct answer is yes. Moral character is produced by making virtuous choices in the circumstances that one confronts in life.

[B]y acting in the various relations in which we are thrown with our fellow men, we come to be, some just, some unjust ; and by acting in dangerous positions and being habituated to feel fear or confidence, we come to be, some brave, others cowards. Similarly is it also with respect to the occasions of lust and anger: for some men come to be perfected in self-mastery and mild, others destitute of all self-control and passionate; [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 50).]

It is through a long series of virtuous choices that praiseworthy dispositions such as bravery, self-mastery, and liberality are produced.

To develop such virtues, Aristotle argues that one must be free to choose, the object of one’s choice must be feasible, and the consequences intentional. He imagines a multistage decision process of identifying ends, choosing actions, and implementing actions.

Having thus drawn out the distinction between voluntary and involuntary action, our next step is to examine into the nature of moral choice; because this seems most intimately connected with virtue, and to be a more decisive test of moral character than a man's acts are. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p.

72).]

[T]he object of moral choice is something in our own power , which is the object of deliberation and the grasping of the will. So, moral choice must be a grasping after something in our own power consequent upon deliberation, because after having deliberated we decide, and then grasp by our will in accordance with the result of our deliberation. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 77).]

Since the end is the object of wish, and the means to the end of deliberation and Moral Choice, the actions regarding these matters must be in the way of moral choice, i.e. voluntary. The acts of working out the virtues are such actions, and therefore virtue is in our power.

And so too is Vice . [ Nicomachean Ethics (pp.

78-79).]

Furthermore, it is wholly irrelevant to say that the man who acts unjustly or dissolutely does not wish to attain the habits of these vices: for if a man wittingly does those things whereby he must become unjust he is to all intents and purposes unjust voluntarily; [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 80).]

Not all choices are moral choices, but all moral actions are voluntary.

Moreover, we are responsible for our own moral character.

3

Aristotle notes that even in cases in which the ends to be advanced are not entirely products of the individual--as with our needs for food and water-- the means to those ends are chosen by the individual. Thus, we are all personally responsible for both our virtues and vices.

4

3

4

A similar argument will be much later used by John Locke in his famous (1689) letter on religious tolerance.

Aristotle mentions other factors that affect what an economist might regard as the cost of virtuous choices including early teaching, birth status, and wealth. But at the margin, it is choices in the circumstances confronted that determine all of one’s virtues. page 5

5

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

Whether we suppose that the end impresses each man's mind with certain notions not merely by nature, but that there is somewhat also dependent on himself , or that the end is given by nature, virtue is voluntary because the good man does all the rest voluntarily . ... [T]he vices must be voluntary also, because the cases are exactly similar.

. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 82).]

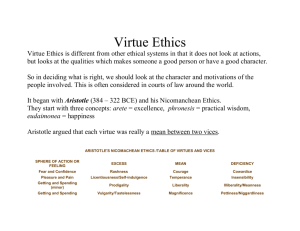

V. Virtue as a “golden mean”

If perfecting one’s moral character requires virtuous choices, is there anything general that can be said about virtue? Aristotle's suggests that virtues are generally means between extremes that are considered vices. His demonstration of this is largely empirical in that he reviews widely acknowledged virtues and attempts to show that they are all in between two vices. Virtues are all praiseworthy activities.

5 thumb is thus to be moderate in all things.

Vices are not. A useful rule of

I. In respect of fears and confidence or boldness: The Mean state is Courage: men may exceed, of course, either in absence of fear or in positive confidence: the former has no name (which is a common case), the latter is called rash: again, the man who has too much fear and too little confidence is called a coward.

II. In respect of pleasures and pains (but not all, and perhaps fewer pains than pleasures): The Mean state here is perfected Self-mastery, the defect total absence of

Self-control. As for defect in respect of pleasure, there are really no people who are chargeable with it, so, of course, there is really no name for such characters, but, as they are conceivable, we will give them one and call them insensible.

III. In respect of giving and taking wealth (a): The mean state is Liberality, the excess Prodigality, the defect

Stinginess: here each of the extremes involves really an excess and defect contrary to each other: I mean, the prodigal gives out too much and takes in too little, while the stingy man takes in too much and gives out too little. (It must be understood that we are now giving merely an outline and summary, intentionally: and we will, in a later part of the treatise, draw out the distinctions with greater exactness.) [ Nicomachean Ethics (pp. 60-61).]

Next let us speak of Perfected Self-Mastery , which seems to claim the next place to Courage, since these two are the

Excellences of the Irrational part of the Soul. That it is a mean state , having for its object-matter Pleasures ...

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 91).]

We will next speak of Liberality . Now this is thought to be the mean state, having for its object-matter Wealth : I mean, the Liberal man is praised not in the circumstances of war, nor in those which constitute the character of perfected self-mastery, nor again in judicial decisions, but in respect of giving and receiving Wealth, chiefly the former.

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 97).]

In respect of truth: The man who is in the mean state we will call Truthful, and his state Truthfulness, and as to the disguise of truth, if it be on the side of exaggeration,

Braggadocio, and him that has it a Braggadocio; if on that of diminution, Reserve and Reserved shall be the terms.

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 62). ]

Self mastery is given considerable attention in his discussion of virtues, which suggests that it is in Aristotle’s mind the most important of the moral virtues. The self mastery that he has in mind is not one of pure

Praiseworthy activities will move to center stage in Adam Smith’s theory of moral sentiments as developed in chapter xx.

page 6

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 asceticism or self denial, however, because that would not be consistent with achieving happiness.

6

[T]he man of perfected self mastery is in the mean with respect to these objects: that is to say, he neither takes pleasure in the things which delight the vicious man, and in fact rather dislikes them, nor at all in improper objects; nor to any great degree in any object of the class; nor is he pained at their absence; nor does he desire them; or, if he does, only in moderation, and neither more than he ought, nor at improper times, and so forth ; but such things as are conducive to health and good condition of body, being also pleasant, these he will grasp at in moderation and as he ought to do, and also such other pleasant things as do not hinder these objects, and are not unseemly or disproportionate to his means.

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 95).]

Many translators of Aristotle use the term “meek” to describe what

Aristotle refers to as self mastery or reasonableness. Others use the words temperate or prudent rather than meek, although neither seems to fully capture what Aristotle is interested in: self mastery.

7

For the notion represented by the term meek man is the being imperturbable, and not being led away by passion , but being angry in that manner, and at those things, and for that length of time, which reason may direct . [

Nicomachean Ethics (p. 114).]

Aristotle develops a much longer list of virtues than need to be covered for the purposes of this book. He uses the list to provide guidance about what sorts of dispositions one should invest in and to demonstrate that all those dispositions tend to be means between extremes that are widely regarded to be vices.

Aristotle also acknowledges that in ethics, as in many other parts of reality, universal principles are impossible, or at least cannot be discovered by man because of irreducible errors in observation and reasoning. In these areas of life, practical wisdom can substitute for universality in that it allows good actions to be chosen in situations in which general principles fail to provide clear guidance.

8

Man's work as Man is accomplished by virtue of

Practical Wisdom and Moral Virtue , the latter giving the right aim and direction, the former the right means to its attainment; [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 167).]

VI. Economic Exchange as an Instance of Just Relations between Men

All but one of the Aristotelian virtues are in the interest of the individual himself to develop. This is because ethics is concerned with self

6

7

The man of perfected mastery differs from the man of perfect self control by his absence of need for or temptation to vices. The man of perfect self control, feels those desires, but is able to resist such temptations.

Note that the above was written nearly a half century before the new testament’s “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth” (Matthew 5.5). Perhaps, the same sense of the word “meek” was intended when the new testament was written and intended to imply self mastery as in Aristotle, rather than the modern usage,

8 which characterizes a timid person.

The distinction between science and practical wisdom is similar to and foreshadows both Knightian and Shacklian uncertainty, ideas worked out in the 20th century. In Aristotle’s analysis, first principles arise from intuition rather than deduction. “[T]he faculty which takes in first principles cannot be any of the three first; the last, namely Intuition, must be it which performs this function .” [Ethics (p. 158).] Thus, “Science is the union of Knowledge and Intuition .” [Ethics (p. 159)].

This argument will be used by Spencer as a foundation for utilitarianism--which Aristotle has obliquely already adopted.

page 7

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 improvement that increase lifetime happiness, rather than the welfare of others. Justice is the only virtue that benefits others more than oneself.

Justice alone of all the virtues is thought to be a good to others , because it has immediate relation to some other person, inasmuch as the just man does what is advantageous to another, either to his ruler or fellow-subject . [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 127).]

With respect to justice, he argues that it has several meanings, some of which are consistent with his mean state theory of virtue.

Justice , it must be observed, is a mean state not after the same manner as the forementioned virtues , but because it aims at producing the mean , while injustice occupies both the extremes. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 137).]

Justice is the moral state in virtue of which the just man is said to have the aptitude for practicing the just in the way of moral choice, and for making division between himself and another , or between two other men, not so as to give to himself the greater and to his neighbor the less share of what is choice worthy and contrariwise of what is hurtful, but what is proportionably equal , and in like manner when adjudging the rights of two other men. [ Nicomachean

Ethics (p. 138).]

The notion of justice that attracts most of Aristotle’s attention is that with respect to what might be called fairness or just deserts. Just relations between men and women are those that are fair in the sense that rewards are “proportionate.”

The just, then, is a certain proportionable thing . For proportion does not apply merely to number in the abstract, but to number generally, since it is equality of ratios ,

[ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 131).]

Reciprocity requires a balance in relationships among persons that is just. For example, I do a favor for you, and you reciprocate with a proportionate favor to me. In others, it may involve violence, you hurt me in some way, and I will do the same to you, as with an “eye for an eye.” It is reciprocity , Aristotle argues, that reciprocity holds society together.

[I]n dealings of exchange such a principle of justice as this reciprocation forms the bond of union , but then it must be reciprocation according to proportion and not exact equality , because by proportionate reciprocity of action the social community is held together , [ Nicomachean

Ethics (p. 134).]

Money and money prices allow goods and services to be compared to one another.

[T]hat all things which can be exchanged should be capable of comparison , and for this purpose money has come in, and comes to be a kind of medium, for it measures all things and so likewise the excess and defect; for instance, how many shoes are equal to a house or a given quantity of food.

As then the builder to the shoemaker, so many shoes must be to the house (or food, if instead of a builder an agriculturist be the exchanging party); for unless there is this proportion there cannot be exchange or dealing, and this proportion cannot be unless the terms are in some way equal . [ Nicomachean Ethics (pp. 135-136).)

Let A represent an agriculturist, C food, B a shoemaker, D his wares equalized with A's. Then the proportion will be correct , A:B::C:D; now reciprocation will be practicable, if it were not, there would have been no dealing. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 136).]

Aristotle is among the first to argue that money allows comparisons which are necessary for the calculation of just (or fair) terms of trade. Money allows proportionate justice to be satisfied, because it serves as a medium of exchange and store of value. page 8

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

Exchange is also a voluntary activity.

Now that what connects men in such transactions is

Demand [money], as being some one thing, is shown by the fact that, when either one does not want the other or neither want one another, they do not exchange at all: whereas they do when one wants what the other man has, wine for instance, giving in return corn for exportation.

And further, money is a kind of security to us in respect of exchange at some future time . [ Nicomachean Ethics (pp.

136-137).]

However, Aristotle notes that the value of money, itself, is not absolute. It may decrease (what we would refer to as a risk of inflation).

the theory of money being that whenever one brings it one can receive commodities in exchange: of course this too is liable to depreciation, for its purchasing power is not always the same , but still it is of a more permanent nature than the commodities it represents. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 137).]

In markets, proportionate reciprocity is determined by relative prices. Rather than equality in weight or numbers, proportionate justice in exchange involves equality of market value (which is determined by money prices). In this respect, markets can be said to have a foundation that is consistent with justice. Money is not the “root of all evil” as is sometime claimed, but provides a basis for just exchange.

The common measure must be some one thing , and also from agreement (for which reason it is called nomisma), for this makes all things commensurable : in fact, all things are measured by money.

Let B represent ten minæ, A a house worth five minæ, or in other words half B, C a bed worth 1/10th of B: it is clear then how many beds are equal to one house, namely, five.

It is obvious also that exchange was thus conducted before the existence of money : for it makes no difference whether you give for a house five beds or the price of five beds. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 137).]

In its first role, money is a “veil” in that the same trades conceptually could have been done without money.

In this short section of the Ethics , Aristotle invents several important ideas in economics and indirectly suggests that exchange (at equilibrium prices) promotes reciprocity and just relations among men and women.

Aristotle’s proportionate equality of exchange is implied by competitive equilibrium prices, a concept not to be developed for more than two thousand years. At that equilibrium, there are no unrealized gains to trade and no profits (in the Marshallian case). In that case, relative prices are such that they produce Aristotle’s equality of value and proportions. In contemporary welfare economics, the “zero profit” norm, perhaps surprisingly, continues to plays a role in normative assessments of markets.

9

For the purposes of this book, it is important to note that Aristotle’s contributions to economic theory are developed in order to illustrate the relevance of his theories of moral choice, justice, and reciprocity.

Commerce simply illustrates what he means by proportionate justice.

9 Aristotle’s principle of proportionality holds at a long run competitive equilibrium. Let P

1

X

1

= P

2

X

2

= P

3

X

3 in equilibrium, where 1,2,3 indicate different goods and the prices are all equilibrium prices for those goods. The X’s then indicate quantities of goods that would be traded when proportionate justice holds. It is the equivalence of money values that makes them just or fair in this sense. Note that the proportions of X

1

and X

2

satisfy P

1

/P

2

= X

2

/X

1

. The no profit condition of

Marshallian long run equilibrium implies that the amounts paid for goods exactly equals their cost of production. If there are no speculative gains possible, then the money equivalence condition tends to hold across all goods.

page 9

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

Nonetheless, Aristotle has some reservations about the kind of behavior that markets tend to induce that are worked out, also in passing, in his next book, the Politics .

VII. Justice, Virtue, and the Law

At various points in the Ethics , Aristotle takes up the extent to which virtue can be promoted through law. That is to say, the extent can public policies promote the moral development of the persons living in the polity of interest. Aristotle argues that virtuous dispositions remain ultimately the product of personal choice, but virtuous choices can be encouraged through good public laws.

The Laws too give directions on all points, aiming either at the common good of all, or that of the best, or that of those in power (taking for the standard real goodness or adopting some other estimate); in one way we mean by

Just, those things which are apt to produce and preserve happiness and its ingredients for the social community. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p. 126).]

A good legal/regulatory system promotes virtue by encouraging moral choices.

Further, the Law commands the doing the deeds not only of the brave man (as not leaving the ranks, nor flying, nor throwing away one's arms), but those also of the perfectly self-mastering man, as abstinence from adultery and wantonness ; and those of the meek man, as refraining from striking others or using abusive language : and in like manner in respect of the other virtues and vices commanding some things and forbidding others, rightly if it is a good law , in a way somewhat inferior if it is one extemporized. [ Nicomachean Ethics (p.

126).]

In this manner, Aristotle shifts his focus from private ethics--how one may perfect oneself and become a happier, more complete, and more praiseworthy person--to an examination of institutions.

In connecting justice as a private virtue with justice in the legal sense, he argues that a community's laws can be just insofar as they are produced through just procedures and tend to preserve or promote happiness. In this he presages the utilitarian and contractarian analysis of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His next book , the Politics , is entirely focused on such issues.

However, his difficulty in creating more than an general outline for ethical behavior implies that developing a perfect, universal, set of laws will also be impossible.

[Although] there is a necessity for general statement, a general statement cannot apply rightly to all cases ,

[T]he law takes the generality of cases, being fully aware of the error thus involved; and rightly too notwithstanding, because the fault is not in the law, or in the framer of the law, but is inherent in the nature of the thing , because the matter of all action is necessarily such.

When then the law has spoken in general terms, and there arises a case of exception to the general rule, it is proper, in so far as the lawgiver omits the case and by reason of his universality of statement is wrong, to set right the omission by ruling it as the lawgiver himself would rule were he there present , [Aristotle (2012-05-17). Ethics

(p. 149).]

VIII. Economics and Ethics in the Politics

Towards the end of Ethics , after discussing friendship as an important example of reciprocity and exchange, Aristotle shifts back to an analysis of institutions, especially political institutions. These are naturally of interest insofar as he believes that good laws promote virtue and social cohesion, page 10

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 but also because he believes that ideas of proportionate justice vary with political institutions. The Politics was written after the Nicomachean Ethics and numerous references to the Ethics appear in the Politics .

The Politics focuses for the most part on the properties of political institutions rather than ethics or moral choices. However, good institutions and virtuous conduct are not entirely independent of one another. For example, good institutions encourage people to become virtuous. Both good laws and public education tend to have this effect. He is also interested in how political and legal institutions affected prosperity.

In Greece, during Aristotle’s time, there were a number of city-state experiments concerning property. In some places, there was little or no private property, in others, most things were private, with relatively little in common. This allowed Aristotle to observe and attempt to generalize the effects that alternative property laws had on various aspects of society.

A. Aristotle on Private Property

A few Greek scholars, as with Socrates, had advocated common ownership. Aristotle challenged their support of communal property, arguing that in many cases it would lead to undesirable results. He notes many practical problems associated with communal property and advantages of private property. Many of theses are similar to ones developed in contemporary law and economics research.

The members of a state must either have (1) all things or (2) nothing in common, or (3) some things in common and some not.

That they should have nothing in common is clearly impossible , for the constitution is a community, and must at any rate have a common place- one city will be in one place, and the citizens are those who share in that one city . [ Politics (KL 371-373).] 10

That all persons call the same thing mine in the sense in which each does so may be a fine thing, but it is impracticable; or if the words are taken in the other sense, such a unity in no way conduces to harmony.

And there is another objection to the proposal. For that which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Every one thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest; and only when he is himself concerned as an individual. For besides other considerations, everybody is more inclined to neglect the duty which he expects another to fulfill. [ Politics (KL

405-409).]

In framing an ideal we may assume what we wish, but should avoid impossibilities.

[ Politics (KL 528).]

He concludes that property should generally be private because there will be fewer disputes and a community’s resources will be used more effectively ( Politics, KL 458-460). There are exceptions, as within families and between friends, but these are exceptions, not the main instance.

Aristotle argues that ownership itself can be a source of pleasure.

Some degree of self interest is natural, and not likely to disappear with common property. Moreover, private property contributes both to personal happiness and the development of virtue.

Again, how immeasurably greater is the pleasure, when a man feels a thing to be his own ; for surely the love of self is a feeling implanted by nature and not given in vain, although selfishness is rightly censured; this, however, is not the mere love of self, but the love of self in excess , like the miser's love of money; for all, or almost all, men love money and other such objects in a measure.

And further, there is the greatest pleasure in doing a kindness or service to friends or guests or companions, which can only be rendered when a man has private

10 KL denotes Kindle Location, an alternative metric to the standard page-count measure, necessary because digital versions of books can be paginated in various ways according to desired fonts and spacing.

page 11

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 property . These advantages are lost by excessive unification of the state. [ Politics (KL 466-470)].

The exhibition of two virtues , besides, is visibly annihilated in such a state: first, temperance towards women (for it is an honorable action to abstain from another's wife for temperance' sake); secondly, liberality in the matter of property. No one, when men have all things in common, will any longer set an example of liberality or do any liberal action; for liberality consists in the use which is made of property. [ Politics (KL 470-473)]

Some of his fellow Greeks argue that private property causes various problems in society. However, Aristotle suggests that their illustrations are really matters of human nature rather than consequences of private property.

[L]egislation [placing everything in common] may have a specious appearance of benevolence; men readily listen to it, and are easily induced to believe that in some wonderful manner everybody will become everybody's friend, especially when some one is heard denouncing the evils now existing in states, suits about contracts, convictions for perjury, flatteries of rich men and the like , which are said to arise out of the possession of private property.

These evils, however, are due to a very different causethe wickedness of human nature . Indeed, we see that there is much more quarreling among those who have all things in common, though there are not many of them when compared with the vast numbers who have private property. [ Politics (KL 458-477).]

Overall, Aristotle’s case in support of private property rests on a variety practical advantages associated with it. There are benefits and costs, but the benefits are far greater than the costs.

Again, we ought to reckon, not only the evils from which the citizens will be saved, but also the advantages which they will lose. The life which they are to lead [in Plato’s ideal community] appears to be quite impracticable.

[ Politics (KL 473-479)]

Communal ownership is impractical, because of what economists would later refer to as the free rider problem and also because it undermines at least two important virtues and eliminates a significant source of pleasure.

B. Aristotle on Investment, Profits, and Interest

Aristotle's ethics suggests that virtuous behavior is always moderate, the mean between two extremes. For this reason, he regards a lust for money as opposed to a moderate regard for it to be a vice rather than a virtue. He implies, although he does not directly say, that some occupations tend to encourage an excessive regard for money, whereas others encourage a more appropriate regard.

There are two sorts of wealth-getting , as I have said; one is a part of household management , the other is retail trade : the former necessary and honorable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another.

The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of an modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural . [ Politics (KL

277-282)]

[T]he art of wealth-getting which consists in household management, on the other hand, has a limit; the unlimited page 12

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 acquisition of wealth is not its business. [Aristotle

(2009-07-02). Politics (Penguin Classics) (KL 250-253)] ]

Aristotle, thus, makes an ethical case in support of what might be called production and exchange (household management) and against commerce and what Kirzner (1978) would much later call

Entrepreneurship.

Productive activities are both necessary and admirable, but the trading of already produced items for profits is less so. And the exchange of money for interest (usury) even less than that. Aristotle’s concern seems to be the excessive interest in money and lack of fairness in bargains that take place between traders and bankers. Opposition to interest rates (usury) and support for farming over commerce remained central beliefs of many persons for much of the next two thousand years and was promoted through public policies.

He is, however, not opposed to maximizing profit, per se. For example he suggests that farmers should know the rate of return from alternative investments in the productive part of the economy:

The useful parts of wealth-getting are, first, the knowledge of livestock which are most profitable, and where, and how as, for example, what sort of horses or sheep or oxen or any other animals are most likely to give a return.

A man ought to know which of these pay better than others , and which pay best in particular places, for some do better in one place and some in another.

Secondly, husbandry, which may be either tillage or planting, and the keeping of bees and of fish, or fowl, or of any animals which may be useful to man. These are the divisions of the true or proper art of wealth-getting and come first. [ Politics (KL 284-288).]

Of the other, which consists in exchange, the first and most important division is commerce (of which there are three kinds the provision of a ship, the conveyance of goods, exposure for sale- these again differing as they are safer or more profitable) ... [ Politics (KL 288-290).]

Although Aristotle does not say as much, he is probably also rejecting commerce as an activity because it violates his concept of proportionate justice. To profit, one must purchase a good at one price and sell it at another, which requires two different trading ratios, both of which cannot satisfy proportionate justice.

He also notes the existence of a third general category of occupations that lies between the productive and unproductive ones.

[A] third sort of wealth getting intermediate between this and the first or natural mode which is partly natural, but is also concerned with exchange, viz., the industries that make their profit from the earth, and from things growing from the earth which, although they bear no fruit, are nevertheless profitable; for example, the cutting of timber and all mining. [ Politics (KL 291-293).]

That mining and timber were acceptable occupations although not as appropriate as farming, carpentry, or sculpture is of interest, because it suggests that innovations in metallurgy were considered to be less important than the production of food and wine by educated Greeks at that time--and by many others until the nineteenth century.

It is doubtful that this rough ranking of honorable economic professions was original with Aristotle, but that his work was read for many centuries afterwards, makes his remarks on this subject important.

It is not clear where his own occupation as educator fits into this hierarchy. Aristotle was not independently wealthy, but earned a living teaching and running a school, where knowledge was traded for money. He regarded this as a form of household production or perhaps he regarded teaching as outside markets and so beyond economics.

page 13

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

IX. Lessons from Aristotle

Perhaps the most important lesson from Aristotle is his methodology.

He listens and observes widely and then attempts to distill general, logically consistent categories and relationships from that body of knowledge. To do so, requires being alert for similarities and connections, but also to contradictions and limitations of both one’s own and other person’s theories. Aristotle works until he is satisfied with the essential principles and relationships that he believes to exist.

The result is partly empirical in that they are partly drawn from observations from life and nature and also because the theories created have to be consistent with life and nature. Other methodologies, statistical and experimental ones, have been added in the past few centuries, but his remains the most used foundation for reason-based theories of living and nature. It is arguably the main method that economic theorists use today.

With respect to human life and ethics, he argues that the happiness

(contentment) is an ultimate end of human action in general and ethics in particular. This is best achieved by working to perfect the soul, ones own character or nature. Excellence in the moral soul is achieved by mastering various virtues, which are acquired through deliberate choices. Intellectual excellence comes from past teaching, experience, and reflection.

The virtues, he suggests, are not extreme forms of behavior but tend to be moderate ones between two extremes. They are not hopeless ideals, but possible for most humans. Vice is equally possible, however, and occurs at the extremes. A good life is not that of a monk, but of an active person who strives to perfect himself, which is in a sense largely self centered.

Ethics for the most part is a personal matter, although concern for others emerges directly through the virtue of justice. Other virtues may also indirectly provide benefits for others, as with bravery and honesty, but this is not the reason one should invest in them. Rather, it is to perfect one’s character and increase one’s lifetime happiness (eudaimonia).

With respect to economics, he suggests that trade (fair trade) involves proportionate reciprocity or justice. The value of what is traded is the same in money terms, which assures that the just ratios of goods are traded.

Money both facilitates exchange and by allowing goods to be compared helps assure that trade is justly done.

With respect to property, he suggests that property systems that are largely private tends to produce better results than one that consists largely or only of common property. Private property reduces conflict, encourages work, and can facilitate the development of virtues, especially liberality

(appropriate levels of generosity) and temperance (resisting temptations, here as with theft or trespass). Ownership can also be a source of pleasure for its owners.

With respect to economic activities themselves, he regards directly production ones (as with farming, carpentry, shoemaking, sculpture, etc.) to be the most honorable professions and most consistent with a good life.

These are followed by professions that simply harvest the fruits of nature rather than producing something of value (as with mining and timbering), followed by traders of merchandise (merchants and speculators) and lastly by those who deal in money (banking and finance).

This rank order of professions is implicitly a rank order of the virtue or tendencies toward virtue that he associates with them. The most virtuous occupations promote moderation and excellence, the least promotes excessive concern with money and unjust behavior.

This order is a bit surprising, since Athens at this time was a great center of commerce. Commerce accounted for much of the wealth and prestige of the city. On the other hand, this perspective was common for the next two thousand years, and remains somewhat common still. The latter may be partly a consequence of Aristotle’s writing on this point, since so many others read and were influenced by it.

Although Aristotle was skeptical of commerce and banking, many of his virtues are market supporting in that they imply conduct that tends to make markets less risky, as with self-mastery and honesty.

With respect to politics (see the appendix of this chapter), he argues that the aim of a good government is to promote the happiness of its people which requires encouraging their moral and intellectual page 14

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 development. He concludes that democracies based on a middle class are the best and most robust forms of government. This is partly because one has to be free to develop one’s character, but also because the choices made tend to be moderate ones and so likely to virtuous ones. In a society that lacks a large middle class, he suggests that other forms of governments, including mixed ones may work as well or better than democracy.

Both his methodology and many of his conclusions accord well with contemporary intuitions about the good life, good society, and good government--although his ideas and analysis came thousands of years before liberal democracies and utilitarian philosophy came into existence.

That this is so, shows that his categories and deductions based on them were more or less on target. That is to say, his categories and the relationships among them are sufficiently general and universal that they still are largely consistent with our moral intuitions.

There is also material in Aristotle’s work that is less relevant and less appealing to modern sensibilities. Most of these also stood the test of time quite well, being mainstream well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

11 For example, his positions on woman’s rights and slavery would have been moderate ones in Western society up until the early nineteenth century. Some of his ideas about education, property, and common meals also seem strange, but it should be kept in mind that Greece was a pre-industrial society, based on trade and agriculture, and states were much smaller then (often relatively small towns with less than 5000 full citizens.)

His strong support for public education would have been relatively extreme in most societies until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The next chapter of part I suggests that mainstream opinion about the role of commerce in a good life were not so different from Aristotle’s in

1500. However, acceptance of the role of markets and commerce in a good or virtuous life gradually changed over the next three centuries.

11 Here it bears noting that some portion of Aristotle’s writing on Ethics, Economics, and Politics seem archaic; for example, his treatment of slavery (which would have been the moderate stance in Europe until around 1800), and also of the rights of women (which would also have been moderate in Europe until around 1800). Some of his remarks on the distribution of property (to be held by citizens but not husbandmen), also clashes with modern intuitions about society--in part because he supports limited (property or education based) participation in government , rather than universal suffrage or completely open political offices.

page 15

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

X. Appendix: Aristotle on Political Institutions

The Politics , explores a variety of issues associated with the state. Many of the constitutional issues are beyond the scope of this book, although it is interesting to see how much of Aristotle’s analysis of political systems remains relevant today. Some parts of the Politics are directly relevant for part III of the book, which analyses relationships between ethics, markets, and public policy. A short overview of these is developed in this appendix.

During Aristotle’s era, there were many different kinds of governments in the various city states in the area that we now call Greece and Western Turkey. There was really no such thing as “Greece” during this time, although there were alliances, trading networks, and linguistic communities. As in the Ethics , an amazing number of issues are dealt with

(usually briefly), many of which disappeared from serious intellectual and public debates in the period after the collapse of the Roman Republic around 60 BC) until around the year 1576, when the Dutch republic was founded.

When several villages are united in a single complete community, large enough to be nearly or quite self-sufficing, the state comes into existence, originating in the bare needs of life, and continuing in existence for the sake of a good life . [ Politics (KL 65-66).]

The state -- by which he means a political community -- is natural feature of human society. Individuals acting alone are not self sufficient, whereas (some) communities are. A group of communities with a government (state) is more self-sufficient than ones without a government.

The state increases the survival prospects of individuals and can increase their virtue and happiness, is thus a great invention. (This point would much later (in 1651) be the basis of Hobbes’ contract theory of the state.)

The proof that the state is a creation of nature and prior to the individual is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole.

Below is a short overview of his analysis of good government, much of which was known to the founders and proponents of more representative institutions in the centuries in which democratic institutions emerged in the West (from roughly 1600-1900).

12

EVERY STATE is a community of some kind, and every community is established with a view to some good; for mankind always acts in order to obtain that which they think good.

[

He who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state. A social instinct is implanted in all men by nature, and

Politics (KL 80-83)].

yet he who first founded the state was the greatest of benefactors

[I]f all communities aim at some good, the state or political community, which is the highest of all, and which embraces all the rest, aims at good in a greater degree than any other, and at the highest good . [Politics

(KL 34-37).]

There are also prerequisites for all political communities (states) including: (1) food, (2) arts, (3) arms (held by the citizens), (4) revenues, (5) religion, (6) a method of choosing policies and resolving disputes.

Let us then enumerate the functions of a state, and we shall easily elicit what we want:

First, there must be food; secondly, arts, for life requires many instruments;

12 studied.

For much of this period, it bears noting, most educated persons learned Greek in order to read Aristotle, Plato, Socrates etc. in the original. Latin was also widely page 16

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 thirdly, there must be arms, for the members of a community have need of them, and in their own hands, too, in order to maintain authority both against disobedient subjects and against external assailants; fourthly, there must be a certain amount of revenue, both for internal needs, and for the purposes of war; fifthly, or rather first, there must be a care of religion which is commonly called worship; sixthly, and most necessary of all there must be a power of deciding what is for the public interest, and what is just in men's dealings with one another.

These are the services which every state may be said to need . For a state is not a mere aggregate of persons, but a union of them sufficing for the purposes of life ; and if any of these things be wanting, it is as we maintain impossible that the community can be absolutely self-sufficing. [ Politics (KL 2869-2876).]

Although governments are always necessary, some forms of government are better than others. He suggests that the institutions of good government can be analyzed in the same manner as ethics, by looking at existing governments and attempting to discern universal principles from them. He argues that the lawgivers (rulers, whether elected or not) can exhibit virtue and vice just as ordinary men can. And, he also argues that lawmakers should attempt to increase the level of virtue and thereby happiness in their communities.

In the end, he supports democratic or mixed forms of government depending on the income distribution in the communities to be governed.

[T]hose who care for good government take into consideration virtue and vice in states .

Whence it may be further inferred that virtue must be the care of a state which is truly so called, and not merely enjoys the name: for without this end the community becomes a mere alliance which differs only in place from alliances of which the members live apart; and law is only a convention, 'a surety to one another of justice,' [ Politics (KL 1100-1103].

There is also a doubt as to what is to be the supreme power in the state : Is it the multitude? Or the wealthy? Or the good? Or the one best man? Or a tyrant? Any of these alternatives seems to involve disagreeable consequences.

[ Politics (KL 1121-1123).]

If government officers (magistrates) are to be elected, who should be the voters?

Does not the same principle apply to elections? For a right election can only be made by those who have knowledge ; those who know geometry, for example, will choose a geometrician rightly, and those who know how to steer, a pilot; and, even if there be some occupations and arts in which private persons share in the ability to choose, they certainly cannot choose better than those who know.

So that, according to this argument, neither the election of magistrates, nor the calling of them to account, should be entrusted to the many . Yet possibly these objections are to a great extent met by our old answer, that if the people are not utterly degraded, although individually they may be worse judges than those who have special knowledge- as a body they are as good or better. [ Politics (KL 1158-1164).]

This is Aristotle’s hint at what will much later be called the Condorcet

Jury Theorem, that a group may excercise better judgment than any of its members.

Next he suggests that there is no principle that clearly implies who should govern. This indirectly suggests that there is no perfect pure or mixed form of government.

page 17

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2

All these considerations appear to show that none of the principles on which men claim to rule and to hold all other men in subjection to them are strictly right . To those who claim to be masters of the government on the ground of their virtue or their wealth, the many might fairly answer that they themselves are often better and richer than the few- I do not say individually, but collectively. [ Politics

(KL 1223-1226).]

Towards the end of the Politics, after reviewing the advantages and disadvantages of various types of governments and states, Aristotle sketches out the ideal city state and ideal constitution for that state.

Consistent with his approach to Ethics , he suggests that the best constitution creates the greatest opportunity for happiness. His vision of happiness is not strictly speaking a utilitarian concept of the ideal state, although it largely is consistent with that perspective (which emerged around 1800). Happiness requires the development of particular virtues at the level of the individual, a notion missing from most utilitarian analysis.

A nice summary of his main argument in the Nicomachean Ethics is also found in Aristotle’s section on happiness in the Politics (Kindle location

3038). These are partly taught, as he suggests in the Ethics , and partly self developed through experience and choice. The latter implies that the best state will have a large number of freemen.

Returning to the constitution itself, let us seek to determine out of what and what sort of elements the state which is to be happy and well-governed should be composed. [ Politics (KL 2984-2985).]

But since our object is to discover the best form of government , that, namely, under which a city will be best governed, and since the city is best governed which has the greatest opportunity of obtaining happiness , it is evident that we must clearly ascertain the nature of happiness. [ Politics (KL 2993-2994).] the form of government is best in which every man, whoever he is, can act best and live happily . [ Politics (KL

2718-2719).]

We maintain, and have said in the Ethics, if the arguments there adduced are of any value, that happiness is the realization and perfect exercise of virtue, and this not conditional, but absolute. [ Politics (KL 2995-2996).]

If we are right in our view, and happiness is assumed to be virtuous activity, the active life will be the best , both for every city collectively, and for individuals. [ Politics (KL

2769-2770).]

[T]he government of freemen is nobler and implies more virtue than despotic government . [ Politics (KL

3058-3059).]

Aristotle’s analysis of the state also includes a discussion of the role of the state in education. Aristotle favors public education, but the best type of education depends in part on the kind of government in place. In this his opinion differs from some “doctrinaire” liberals such as Adam Smith, who argued that public education is unnecessary. (Adam Smith’s views are discussed in chapter 4.)

[T]he legislator [constitution writer] should direct his attention above all to the education of youth; for the neglect of education does harm to the constitution The citizen should be molded to suit the form of government under which he lives . [ Politics (KL 3172-3174).]

Aristotle notes, however, that there is much disagreement about which virtues to promote. (He notes also that some places place too much emphasis on athletics.) Good governments make/have good laws that are followed by the citizenry. A good citizen should be able to both lead and obey.

[T]he good citizen ought to be capable of both ; he should know how to govern like a freeman, and how to page 18

Ethics and the Commercial Society: Chapter 2 obey like a freeman- these are the virtues of a citizen. And, although the temperance and justice of a ruler are distinct from those of a subject, the virtue of a good man will include both; for the virtue of the good man who is free and also a subject, e.g., his justice, will not be one but will comprise distinct kinds, the one qualifying him to rule, the other to obey, .[ Politics (KL 990-993).]

[T]here are two parts of good government; one is the actual obedience of citizens to the laws, the other part is the goodness of the laws which they obey. [ Politics (KL

1607-1608).]

In the end, the best state is likely to be a more or less democratic state based on middle-class citizens.

The basis of a democratic state is liberty ; which, according to the common opinion of men, can only be enjoyed in such a state; this they affirm to be the great end of every democracy. One principle of liberty is for all to rule and be ruled in turn, and indeed democratic justice is the application of numerical not proportionate equality; whence it follows that the majority must be supreme, and that whatever the majority approve must be the end and the just. [ Politics (KL 2473-2476).]

Thus it is manifest that the best political community is formed by citizens of the middle class, and that those states are likely to be well-administered in which the middle class is large, and stronger if possible than both the other classes, or at any rate than either singly; for the addition of the middle class turns the scale, and prevents either of the extremes from being dominant. [ Politics (KL

1679-1682).]

The mean condition of states is clearly best , for no other is free from faction; and where the middle class is large, there are least likely to be factions and dissensions. For a similar reason large states are less liable to faction than small ones, because in them the middle class is large ;

[ Politics (1685-1687).]

Madison (1782) would much later use similar logic in the Federalist

Paper , number 10. Perhaps surprisingly, Aristotle argues that the viability of a democracy depends partly on the distribution of income, a point that has resurfaced in contemporary political economy.

[D]emocracies are safer and more permanent than oligarchies, because they have a middle class which is more numerous and has a greater share in the government. When there is no middle class, and the poor greatly exceed in number, troubles arise, and the state soon comes to an end.

A proof of the superiority of the middle class is that the best legislators have been of a middle condition, for example, Solon (the principle author of the Athenian constitution). [ Politics (KL 1688-1691).]

[A] government which is composed of the middle class more nearly approximates to democracy than to oligarchy, and is the safest of the imperfect forms of government . [ Politics (KL 1919-1920).]

The arbiter is always the one trusted, and he who is in the middle is an arbiter. (Note that this seems to imply that the arbitrator is median voter, since the median voter is by definition in the middle, but he may also simply mean that arbitrators if they are just take account of both side’s interests.)

Besides promoting virtue and sufficient prosperity for virtue to develop, a good constitution also promotes the longevity of a state or polity.

The more perfect the admixture of the political elements, the more lasting will be the constitution.

[ Politics (KL 1719-1720).] page 19