COMPENSATION & RISK RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

advertisement

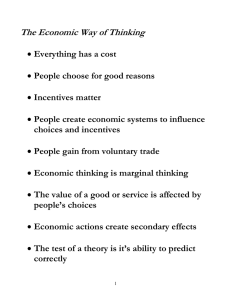

COMPENSATION & RISK RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan Corporate Governance Research Initiative Stanford Graduate School of Business KEY CONCEPTS • Stock options counteract risk aversion. • Executives with a large investment in company equity might become risk averse to preserve their wealth. • Two measures of their investment are relevant: – Delta: ratio of change in value of wealth to 1 percent change in price. – Measures how much executive gains (loses) if stock price goes up (down). – Vega: ratio of change in value of wealth to 1 percent change in volatility. – Measures how much executive gains (loses) if stock volatility goes up (down). KEY CONCEPTS • Executive holding stock: – Delta. Wealth moves dollar-for-dollar (linearly) with stock price. – (1 percent change in stock = 1 percent change in wealth). – Vega. Wealth is unaffected by volatility of stock. Vega = zero. • Executive holding options: – Delta. Wealth moves nonlinearly with stock price. – (1 percent change in stock produces a greater than 1 percent change in wealth). – Vega. Wealth increases with volatility. • Stock options encourage risk taking by giving incentive to increase volatility. STOCK OPTIONS ENCOURAGE “RISKY” INVESTMENT • Rajgopal and Shevlin (2002) examine whether stock options encourage executives to invest in “risky” projects. • Sample: 117 companies in oil and gas industry, 1993-1997. • Findings: executives with stock options: – Make riskier bets on oil exploration, measured by variation in future cash flows. – Are less likely to hedge exposure to oil prices. • Conclusion: stock options encourage managers to invest in higher risk, higher reward projects. STOCK OPTIONS CAN LEAD TO “EXTREME” OUTCOMES • Sanders and Hambrick (2007) study impact of stock options on company performance. • Sample: 950 companies in S&P 1500 Index, 1993-2000. • Findings: executives with stock options: – Increase investment in R&D, capital expenditures, and acquisitions. – Shareholder returns are more “extreme”—both positive and negative. – (In this sample, outcomes were more likely to be negative than positive.) • Conclusion: stock options lead to higher risk, higher return outcomes. “High levels of stock options appear to motivate CEOs to take big risks… to ‘swing for the fences.’” FURTHER EVIDENCE OPTIONS ENCOURAGE RISK TAKING • Coles, Daniel, and Naveen (2006) find that executives with large stock option exposure spend more on R&D, reduce diversification, and increase leverage. • Sample: S&P 1500 companies from 1992-2002. • Isolate the effects of vega and delta (prior studies do not). • Findings: Higher vega leads to riskier choices. • Conclusion: higher sensitivity to stock price volatility gives incentive to take risk. FURTHER EVIDENCE OPTIONS ENCOURAGE RISK TAKING • Gormley, Matsa, and Milbourn (2013) find that executives with fewer options reduce leverage, reduce R&D, hold more cash, and diversify. • Sample: 143 firms with workers exposed to newly discovered carcinogen, 1980s-2000s. • Findings: – Company volatility increases due to litigation risk. – Boards reduce vega of executive portfolio. – Executives respond by reducing firm risk. • Conclusion: lower sensitivity to stock price volatility gives incentive to reduce risk. STOCK OPTIONS CAN LEAD TO SYSTEMIC RISK TAKING • Armstrong and Vashishtha (2012) demonstrate that stock options give CEOs incentive to increase systemic (market) risk but not idiosyncratic (firm-specific) risk. – Sample: 13,233 firm-year observations from 1992-2007. – Isolate the effects of vega on systemic and idiosyncratic risk. – (Systemic risk can be hedged; idiosyncratic risk cannot.) – Find that vega is associated with total and systemic, but not idiosyncratic risk. – (Total risk = systemic risk + idiosyncratic risk.) • Conclusion: higher sensitivity to stock price volatility gives incentive to increase systemic risk, even if choices do not increase firm value. DID STOCK OPTIONS CAUSE THE FINANCIAL CRISIS? • Larcker, Ormazabal, Tayan, and Taylor (2014) demonstrate a significant increase in risk-taking incentives among banks prior to the crisis. • Sample: 3,232 nonbanks, 132 banks, and 58 securitizing banks from 1992-2009 • Average vega of securitizing bank CEO wealth was 15-fold higher in 2006 than 1992. • Average vega was quadruple that of average nonbank CEO in 2006. • Suggests that incentives played a role in bank risk taking. AVERAGE PORTFOLIO VEGA, ALL U.S. CEOs DID STOCK OPTIONS CAUSE THE FINANCIAL CRISIS? • Fahlenbrach and Stulz (2011) find no evidence that stock options caused the financial crisis. • Sample: 95 banks from 2006-2008. • No evidence that banks whose CEOs had greater vega performed worse during the crisis. • No evidence that incentives and performance were different between firms that did and did not receive TARP funding from the government. • Conclusion: incentives did not cause the crisis. “Ex ante, these risks looked profitable for shareholders. Ex post, these risks had unexpected poor outcomes. These poor outcomes are not evidence of CEOs acting in their own interest at the expense of shareholder wealth.” STOCK OPTIONS MIGHT ENCOURAGE MISREPORTING • Armstrong, Larcker, Ormazabal, and Taylor (2013) examine whether stock options are associated with financial misreporting. • Sample: 20,445 firm-year observations (2,446 firms) between 1992-2009. • Find that vega is positively related to future financial restatements. • Conclusion: higher sensitivity to stock price volatility gives incentive to misreport. “Equity portfolios provide managers with incentive to misreport not because they tie the manager’s wealth to equity value, but because they tie the manager’s wealth to equity risk.” FURTHER EVIDENCE OPTIONS ENCOURAGE MANIPULATION • Kim, Li, and Zhang (2011) examine whether CFOs with large option holdings hide bad news to prevent (delay) stock price declines. • Sample: 29,638 firm-year observations between 1993-2009. • Find that abnormally high option holdings are associated with future crashes. • (Crash = one-week stock returns 3.2 standard deviations below mean.) • Conclusion: options encourage managers to hide bad news. CONCLUSION • Stock options encourage risk taking. • Risk taking is positive when it increases company value through investment in attractive (but uncertain) projects. • Risk taking is negative when it involves decisions and behaviors not in the interest of shareholders. • Unfortunately, no standard litmus test exists to differentiate between “acceptable” risk and “excessive” risk. • The board of directors and shareholders need to weigh the potential positive and negative implications of stock option compensation in their companies. BIBLIOGRAPHY Shivaram Rajgopal and Terry Shevlin. Empirical Evidence on the Relationship Between Stock Option Compensation and Risk Taking. 2002. Journal of Accounting & Economics. W. M. Gerard Sanders and Donald C. Hambrick. Swinging for the Fences: The Effects of CEO Stock Options on Company Risk Taking and Performance. 2007. Academy of Management Journal. Jeff L. Coles, Naveen D. Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen. Managerial Incentives and Risk-Taking. 2006. Journal of Financial Economics. Todd A. Gormley, David A. Matsa, and Todd Milbourn. CEO Compensation and Corporate Risk: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. 2013. Journal of Accounting and Economics. Christopher S. Armstrong and Rahul Vashishtha. Executive Stock Options, Differential Risk-taking Incentives, and Firm Value. 2012. Journal of Financial Economics. David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, Brian Tayan, and Daniel J. Taylor. Follow the Money: Compensation, Risk, and the Financial Crisis. September 8, 2014. Stanford Closer Look Series. Rüdiger Fahlenbrach and René M. Stulz. Bank CEO Incentives and the Credit Crisis. 2011. Journal of Financial Economics. Christopher S. Armstrong, David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor. The Relation between Equity Incentives and Misreporting: the Role of Risk-taking incentives. 2013. Journal of Financial Economics. Jeong-Bon Kim, Yinghua Li, and Liandong Zhang. CFOs versus CEOs: Equity Incentives and Crashes. 2011. Journal of Financial Economics.