A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the

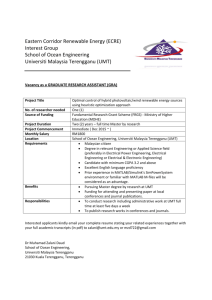

advertisement